Historiography of the Formation of Assamese Identity: a Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyright by Abikal Borah 2015

Copyright By Abikal Borah 2015 The Report committee for Abikal Borah certifies that this is the approved version of the following report: A Region in a Mobile World: Integration of Southeastern sub-Himalayan Region into the Global Capitalist Economy (1820-1900) Supervisor: ________________________________________ Mark Metzler ________________________________________ James M. Vaughn A Region in a Mobile World: Integration of Southeastern sub-Himalayan Region into the Global Capitalist Economy (1820-1900) By Abikal Borah, M. Phil Report Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in partial fulfillment of the degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin December, 2015 A Region in a Mobile World: Integration of Southeastern sub-Himalayan Region into the Global Capitalist Economy (1820-1900) By Abikal Borah, M.A. University of Texas at Austin, 2015 Supervisor: Mark Metzler Abstract: This essay considers the history of two commodities, tea in Georgian England and opium in imperial China, with the objective of explaining the connected histories in the Eurasian landmass. It suggests that an exploration of connected histories in the Eurasian landmass can adequately explain the process of integration of southeastern sub-Himalayan region into the global capitalist economy. In doing so, it also brings the historiography of so called “South Asia” and “East Asia” into a dialogue and opens a way to interrogate the narrow historiographical visions produced from area studies lenses. Furthermore, the essay revisits a debate in South Asian historiography that was primarily intended to reject Immanuel Wallerstein’s world system theory. While explaining the historical differences of southeastern sub-Himalayan region with peninsular India, Bengal, and northern India, this essay problematizes the South Asianists’ critiques of Wallerstein’s conceptual model. -

The First Mohammedan Invasion (1206 &1226 AD) of Kamrupa Took

The first Mohammedan invasion (1206 &1226 AD) of Kamrupa took place during the reign of a king called Prithu who was killed in a battle with Illtutmish's son Nassiruddin in 1228. During the second invasion by Ikhtiyaruddin Yuzbak or Tughril Khan, about 1257 AD, the king of Kamrupa Saindhya (1250-1270AD) transferred the capital 'Kamrup Nagar' to Kamatapur in the west. From then onwards, Kamata's ruler was called Kamateshwar. During the last part of 14th century, Arimatta was the ruler of Gaur (the northern region of former Kamatapur) who had his capital at Vaidyagar. And after the invasion of the Mughals in the 15th century many Muslims settled in this State and can be said to be the first Muslim settlers of this region. Chutia Kingdom During the early part of the 13th century, when the Ahoms established their rule over Assam with the capital at Sibsagar, the Sovansiri area and the area by the banks of the Disang river were under the control of the Chutias. According to popular Chutia legend, Chutia king Birpal established his rule at Sadia in 1189 AD. He was succeeded by ten kings of whom the eighth king Dhirnarayan or Dharmadhwajpal, in his old age, handed over his kingdom to his son-in-law Nitai or Nityapal. Later on Nityapal's incompetent rule gave a wonderful chance to the Ahom king Suhungmung or Dihingia Raja, who annexed it to the Ahom kingdom.Chutia Kingdom During the early part of the 13th century, when the Ahoms established their rule over Assam with the capital at Sibsagar, the Sovansiri area and the area by the banks of the Disang river were under the control of the Chutias. -

CSAP Daily-CA-26-09-2020

CIVIL SERVICES ACHIEVERS' POINT, GUWAHATI THE ASSAM TRIBUNE ANALYSIS Date - 26 September 2020 (For Preliminary and Mains Examination) As per New Pattern of APSC (Also useful for UPSC and other State Level Government Examinations) Join our Regular/Online Classes. For details contact 8811877068 CIVIL SERVICES ACHIEVERS' POINT, GUWAHATI ANSWERS to MCQs of 25-09-2020 1. (b) 1 and 2 only 2. (c) India has already signed such agreement with US, Japan and Germany 3. (c) 1 and 2 only 4. (d) Dengue 5. (a) 3,4 Join our Regular/Online Classes. For details contact 8811877068 CIVIL SERVICES ACHIEVERS' POINT, GUWAHATI MCQs of 26-09-2020 1. Most pandemics have arisen from influenza 2. Total number of member countries in viruses from which of the following animals? UN general assembly is- a) Pigs a) 197 b) Wild birds b) 195 c) Bats c) 201 d) Humans d) 193 Join our Regular/Online Classes. For details contact 8811877068 CIVIL SERVICES ACHIEVERS' POINT, GUWAHATI 3. Budapest convention is related to which of 4. In context with Insolvency and the following: Bankruptcy code (IBC), when can a bank initiate a corporate insolvency resolution (a) Missile technology control process in relation to a corporate debtor? (b) Space nuclearisation (a) On determination of default by (c) Women rights National Company Law Tribunal. (d) Cybercrime (b) Occurrence of default. (c) On net-worth of the debtor becoming negative. (d) On the bank classified the account as Non-Performing Asset. Join our Regular/Online Classes. For details contact 8811877068 CIVIL SERVICES ACHIEVERS' POINT, GUWAHATI 5. Which of the following are the 17 new Sustainable Development Goals? 1) Conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources 2) Reduce inequality within and among countries 3) Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts (a)1, 3 (b) 2, 3 (c) 1, 2 (d) All of the above Join our Regular/Online Classes. -

Social Novel in Assamese a Brief Study with Jivanor Batot and Mirijiyori

JOURNAL OF CRITICAL REVIEWS ISSN- 2394-5125 VOL 7, ISSUE 06, 2020 SOCIAL NOVEL IN ASSAMESE A BRIEF STUDY WITH JIVANOR BATOT AND MIRIJIYORI Rodali Sopun Borgohain Research Scholar, Gauhati University, Assam, India Abstract : Social novel is a way to tell us about problems of our society and human beings. The social Novel is a ‘Pocket Theater’ who describe us about picture of real lifes. The Novel is a very important thing of educational society. The social Novel is writer basically based on social life. The social Novel “Jivonar Batot and Mirijiyori, both are reflect us about problems of society, thinking of society and the thought of human beings. Introduction : A novel is narrative work and being one of the most powerful froms that emerged in all literatures of the world. Clara Reeve describe the novel as a ‘Picture of real life and manners and of time in which it is writter. A novel which is written basically based on social life, the novel are called social novel. In the social Novels, any section or class of the human beings are dealt with. A novel is a narrative work and being one of the most powerful forms that emerged in all literatures of the world particularly during 19th and 20th centuries, is a literary type of certain lenght that presents a ‘story in fictionalized form’. Marion crawford, a well known American novelist and critic described the novel as a ‘pocket theater’, Clara Reeve described the Novel as a “picture of real life and manners and of time in which it is written”. -

Class-8 New 2020.CDR

Class - VIII AGRICULTURE OF ASSAM Agriculture forms the backbone of the economy of Assam. About 65 % of the total working force is engaged in agriculture and allied activities. It is observed that about half of the total income of the state of Assam comes from the agricultural sector. Fig 2.1: Pictures showing agricultural practices in Assam MAIN FEATURES OF AGRICULTURE Assam has a mere 2.4 % of the land area of India, yet supports more than 2.6 % of the population of India. The physical features including soil, rainfall and temperature in Assam in general are suitable for cultivation of paddy crops which occupies 65 % of the total cropped area. The other crops are wheat, pulses and oil seeds. Major cash crops are tea, jute, sugarcane, mesta and horticulture crops. Some of the crops like rice, wheat, oil seeds, tea , fruits etc provide raw material for some local industries such as rice milling, flour milling, oil pressing, tea manufacturing, jute industry and fruit preservation and canning industries.. Thus agriculture provides livelihood to a large population of Assam. AGRICULTURE AND LAND USE For the purpose of land utilization, the areas of Assam are divided under ten headings namely forest, land put to non-agricultural uses, barren and uncultivable land, permanent pastures and other grazing land, cultivable waste land, current fallow, other than current fallow net sown area and area sown more than once. 72 Fig 2.2: Major crops and their distribution The state is delineated into six broad agro-climatic regions namely upper north bank Brahmaputra valley, upper south bank Brahmaputra valley, Central Assam valley, Lower Assam valley, Barak plain and the hilly region. -

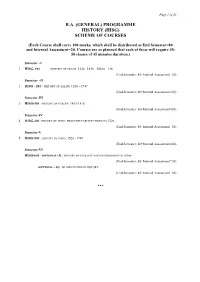

The Proposed New Syllabus of History for the B

Page 1 of 45 B.A. (GENERAL) PROGRAMME HISTORY (HISG) SCHEME OF COURSES (Each Course shall carry 100 marks, which shall be distributed as End Semester=80 and Internal Assessment=20. Courses are so planned that each of these will require 45- 50 classes of 45 minutes duration.) Semester –I 1. HISG- 101 : HISTORY OF ASSAM: 1228 –1826 – Marks= 100 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester –II 2. HISG - 201 : HISTORY OF ASSAM: 1826 – 1947 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester-III 3. HISG-301 : HISTORY OF EUROPE: 1453-1815 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester-IV 4. HISG-401: HISTORY OF INDIA FROM THE EARLIEST TIMES TO 1526 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester-V 5. HISG-501 : HISTORY OF INDIA: 1526 - 1947 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester-VI HISG-601 : (OPTIONAL - I) : HISTORY OF ECOLOGY AND ENVIRONMENT IN INDIA (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) (OPTIONAL – II) : WOMEN IN INDIAN HISTORY (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) *** Page 2 of 45 HISG – 101 End- Semester Marks : 80 In- Semester Marks : 20 HISTORY OF ASSAM: 1228 –1826 Total Marks : 100 10 to 12 classes per unit Objective: The objective of this paper is to give a general outline of the history of Assam from the 13th century to the occupation of Assam by the English East India Company in the first quarter of the 19th century. It aims to acquaint the students with the major stages of developments in the political, social and cultural history of the state during the medieval times. Unit-1: Marks: 16 1.01 : Sources- archaeological, epigraphic, literary, numismatic and accounts of the foreign travelers 1.02 : Political conditions of the Brahmaputra valley at the time of foundation of the Ahom kingdom. -

Assam - a Study on Bihugeet in Guwahati (GMA), Assam

International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR) ISSN: 2319-7064 Impact Factor (2018): 7.426 Female Participation in Folk Music of Assam - A Study on Bihugeet in Guwahati (GMA), Assam Palme Borthakur1, Bhaben Ch. Kalita2 1Department of Earth Science, University of Science and Technology, Meghalaya, India 2Professor, Department of Earth Science, University of Science and Technology, Meghalaya, India Abstract: Songs, instruments and dance- the collaboration of these three ingredients makes the music of any region or society. Folk music is one of the integral facet of culture which also poses all the essentials of music. The instruments used in folk music are divided into four halves-taat (string instruments), aanodha(instruments covered with membrane), Ghana (solid or the musical instruments which struck against one another) and sushir(wind instruments)(Sharma,1996). Out of these four, Ghana and sushirvadyas are being preferred to be played by female artists. Ghana vadyas include instruments like taal,junuka etc. and sushirvadyas include instruments that can be played by blowing air from the mouth like flute,gogona, hkhutuli etc. Women being the most essential part of the society are also involved in the process of shaping up the culture of a region. In the society of Assam since ancient times till date women plays a vital role in the folk music that is bihugeet. At times Assamese women in groups used to celebrate bihu in open spaces or within forest areas or under big trees where entry of men was totally prohibited and during this exclusive celebration the women used to play aforesaid instruments and sing bihu songs describing their life,youth and relation with the environment. -

Women Education in Colonial Assam As Reflected in Contemporary Archival and Literary Records Chiranjib Dahal

SSRG International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Volume 8 Issue 3, 80-86, May-June, 2021 ISSN: 2394 – 2703 /doi:10.14445/23942703/IJHSS-V8I3P112 © 2021 Seventh Sense Research Group® Women Education in Colonial Assam as Reflected In Contemporary Archival And Literary Records Chiranjib Dahal Assistant Professor, Department of History, J.D.S.G. College, Bokakhat Dist.: Golaghat, State: Assam, Country: India 785612 Received Date: 15 May 2021 Revised Date: 21 June 2021 Accepted Date: 03 July 2021 Abstract - The present paper makes an attempt to trace the which can be inferred from literacy rate from 0.2 % in genesis and development of women’s education in colonial 1882 to 6% only in 1947(Kochhar,2009:225). It reveals Assam and its contribution to their changing status and that for centuries higher education for women has been aspirations. The contribution of the native elites in the neglected and the report University Education Commission process of the development of women education; and 1948 exposed that they were against women education. In social perception towards women education as reflected in their recommendation they wrote “women’s present the contemporary periodicals are some other areas of this education is entirely irrelevant to the life they have to lead. study. Educational development in Assam during the It is not only a waste but often a definite disability” colonial rule has generally been viewed by educational (University Education Commission Report, Government of historians to be the work of British rulers who introduced India, 1948-49). Educational development in Assam a system of education with the hidden agenda of initiating during the colonial rule has generally been viewed by a process of socialization. -

Event, Memory and Lore: Anecdotal History of Partition in Assam

ISSN. 0972 - 8406 61 The NEHU Journal, Vol XII, No. 2, July - December 2014, pp. 61-76 Event, Memory and Lore: Anecdotal History of Partition in Assam BINAYAK DUTTA * Abstract Political history of Partition of India in 1947 is well-documented by historians. However, the grass root politics and and the ‘victim- hood’ of a number of communities affected by the Partition are still not fully explored. The scholarly moves to write alternative History based on individual memory and family experience, aided by the technological revolution have opened up multiple narratives of the partition of Assam and its aftermath. Here in northeast India the Partition is not just a History, but a lived story, which registers its presence in contemporary politics through songs, poems, rhymes and anecdotes related to transfer of power in Assam. These have remained hidden from mainstream partition scholarship. This paper seeks to attempt an anecdotal history of the partition in Assam and the Sylhet Referendum, which was a part of this Partition process . Keywords : sylhet, partition, referendum, muslim league, congress. Introduction HVSLWHWKHSDVVDJHRIPRUHWKDQVL[W\¿YH\HDUVVLQFHWKHSDUWLWLRQ of India, the politics that Partition generated continues to be Dalive in Assam even today. Although the partition continues to be relevant to Assam to this day, it remains a marginally researched area within India’s Partition historiography. In recent years there have been some attempts to engage with it 1, but the study of the Sylhet Referendum, the event around which partition in Assam was constructed, has primarily been treated from the perspective of political history and refugee studies. 2 ,W LV WLPH +LVWRU\ ZULWLQJ PRYHG EH\RQG WKH FRQ¿QHV RI political history. -

Power Structure, Discipline, and Labour in Assam Tea Plantations Under Colonial Rule

IRSH 51 (2006), Supplement, pp. 143–172 DOI: 10.1017/S0020859006002641 # 2006 Internationaal Instituut voor Sociale Geschiedenis Power Structure, Discipline, and Labour in Assam Tea Plantations under Colonial Rule Rana P. Behal The tea industry, from the 1840s onwards the earliest commercial enterprise established by private British capital in the Assam Valley, had been the major employer of wage labour there during colonial rule. It grew spectacularly during the last quarter of the nineteenth century, when tea production increased from 6,000,000 lb in 1872 to 75,000,000 lb in 1900 and the area under tea cultivation expanded from 27,000 acres to 204,000 acres.1 Employment of labour in the Assam Valley tea plantations increased from 107,847 in 1885 to 247,760 in 1900,2 and the industry continued to grow during the first half of the twentieth century. At the end of colonial rule the Assam Valley tea plantations employed nearly half a million labourers out of a labour population of more than three-quarters of a million, and more than 300,000 acres were under tea cultivation out of a total area of a million acres controlled by the tea companies.3 This impressive expansion and the growth of the Assam Valley tea industry took place within the monopolistic control of British capital in Assam. An analysis of the list of companies shows that in 1942 84 per cent of tea estates with 89 per cent of the acreage in the Assam Valley were controlled by the European managing agency houses.4 Throughout India, thirteen leading agency houses of Calcutta controlled over 75 per cent of total tea production in 1939.5 Elsewhere I have shown that the tea companies reaped profits over a long time despite fluctuating international prices and slumps.6 One of the most notable features of the Assam Valley tea plantations was that, unlike in the cases of most of the other major industries such as jute, textiles, and mining in British India, it never suffered from a complete 1. -

Unit 23 Central and Eastern India

.UNIT 23 CENTRAL AND EASTERN INDIA Objectives Introduction Malwa Jaunpur Bengal Assam 23.5.1 Kamata-Kamrup 23.5.2 The Ahoms Orissa Let Us sum UP Answers to Check Your Progress Exercises 4 23.0 OBJECTIVES In the present Unit, we will study about regional states in Central and Eastern India during the 13-15th centuries. After reading this Unit, you would learn about: the emergence of regional states in Central and Eastern India, territorial expansion of these regional kingdoms, their relations with their neighbours and other regional states, and 1 their relations with the Delhi Sultanate. 23.4 INTRODUCTION You have already read (in Block 5, Unit 18) that regional kingdoms posed severe threat to the already weakened Delhi Sultanate and with their emergence began the process of the physical disintegration of the Sultanate. In this Unit, our focus would be on the emergence of regional states in Central and Eastern India viz., Malwa, Jaunpur, Bengal, Assam and Orissa. We will study the polity-establishment, expansion and disintegration-of the above kingdoms. You would know how they emerged and succeeded in establishing their hegemony. During the 13th-15th centuries in Central and Eastern India, there emerged two types of kingdoms: a) those whose rise and development was independent of the Sultanate (for example : the kingdoms of Assam and Orissa) and b) Bengal, Malwa and Jaunpur who owed tHeir existencr ru the Sultanate. All these kingdoms were constantlyat war with each other. The nobles, ci,' ;s or rajas and local aristocracy played crucial roles in these confrontations. 23.2 MALWA The decline of the Sultanate paved the way for the emergence bf the independent kingdom of Malwa. -

Renaissance in Assamese Literature

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention ISSN (Online): 2319 – 7722, ISSN (Print): 2319 – 7714 www.ijhssi.org Volume 3 Issue 9 ǁ September. 2014 ǁ PP.45-47 Renaissance in Assamese Literature Dr. Chandana Goswami Associate Professor Dept. of History D.H.S.K. College Dibrugarh, Assam, India ABSTRACT : The paper entitled “Renaissance in Assamese Literature” attempts to highlight the growing sense of consciousness in the minds of the Assamese people. From 1813 to 1854, the year of Wood’s Despatch, this was the period when Assam was experiencing the beginning of a new phase of national life, being thrown into contact with the west. It was trade that had already brought the British salt merchants into Assam. When finally the British took over Assam it had been suffering for a long period from internal disturbances which were closely followed by the Burmese invasions. Education in the country in the early years of British rule was in a retrograde state. In 1837 when Bengali replaced the Assamese as the language of the court, the missionaries had just arrived in Assam. They took up cudgels against the imposition of the Bengali language. The near total darkness shrouding Assam from the outside world was gradually removed with the entry of the British who gradually broke Assam’s isolation by establishing new routes of communication. The educated elite of the time contributed largely towards the development of Assamese literature. I. INTRODUCTION : The term “renaissance” was first used in a specific European context, to describe the great era from about the fourteenth to the sixteenth centuries, when the entire socio-cultural atmosphere of Europe underwent a spectacular transformation.