SUB-REGIONAL NATIONALISM in ASSAM PRINT MEDIA by Joydeep

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyright by Abikal Borah 2015

Copyright By Abikal Borah 2015 The Report committee for Abikal Borah certifies that this is the approved version of the following report: A Region in a Mobile World: Integration of Southeastern sub-Himalayan Region into the Global Capitalist Economy (1820-1900) Supervisor: ________________________________________ Mark Metzler ________________________________________ James M. Vaughn A Region in a Mobile World: Integration of Southeastern sub-Himalayan Region into the Global Capitalist Economy (1820-1900) By Abikal Borah, M. Phil Report Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in partial fulfillment of the degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin December, 2015 A Region in a Mobile World: Integration of Southeastern sub-Himalayan Region into the Global Capitalist Economy (1820-1900) By Abikal Borah, M.A. University of Texas at Austin, 2015 Supervisor: Mark Metzler Abstract: This essay considers the history of two commodities, tea in Georgian England and opium in imperial China, with the objective of explaining the connected histories in the Eurasian landmass. It suggests that an exploration of connected histories in the Eurasian landmass can adequately explain the process of integration of southeastern sub-Himalayan region into the global capitalist economy. In doing so, it also brings the historiography of so called “South Asia” and “East Asia” into a dialogue and opens a way to interrogate the narrow historiographical visions produced from area studies lenses. Furthermore, the essay revisits a debate in South Asian historiography that was primarily intended to reject Immanuel Wallerstein’s world system theory. While explaining the historical differences of southeastern sub-Himalayan region with peninsular India, Bengal, and northern India, this essay problematizes the South Asianists’ critiques of Wallerstein’s conceptual model. -

Numbers in Bengali Language

NUMBERS IN BENGALI LANGUAGE A dissertation submitted to Assam University, Silchar in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Masters of Arts in Department of Linguistics. Roll - 011818 No - 2083100012 Registration No 03-120032252 DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS SCHOOL OF LANGUAGE ASSAM UNIVERSITY SILCHAR 788011, INDIA YEAR OF SUBMISSION : 2020 CONTENTS Title Page no. Certificate 1 Declaration by the candidate 2 Acknowledgement 3 Chapter 1: INTRODUCTION 1.1.0 A rapid sketch on Assam 4 1.2.0 Etymology of “Assam” 4 Geographical Location 4-5 State symbols 5 Bengali language and scripts 5-6 Religion 6-9 Culture 9 Festival 9 Food havits 10 Dresses and Ornaments 10-12 Music and Instruments 12-14 Chapter 2: REVIEW OF LITERATURE 15-16 Chapter 3: OBJECTIVES AND METHODOLOGY Objectives 16 Methodology and Sources of Data 16 Chapter 4: NUMBERS 18-20 Chapter 5: CONCLUSION 21 BIBLIOGRAPHY 22 CERTIFICATE DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS SCHOOL OF LANGUAGES ASSAM UNIVERSITY SILCHAR DATE: 15-05-2020 Certified that the dissertation/project entitled “Numbers in Bengali Language” submitted by Roll - 011818 No - 2083100012 Registration No 03-120032252 of 2018-2019 for Master degree in Linguistics in Assam University, Silchar. It is further certified that the candidate has complied with all the formalities as per the requirements of Assam University . I recommend that the dissertation may be placed before examiners for consideration of award of the degree of this university. 5.10.2020 (Asst. Professor Paramita Purkait) Name & Signature of the Supervisor Department of Linguistics Assam University, Silchar 1 DECLARATION I hereby Roll - 011818 No - 2083100012 Registration No – 03-120032252 hereby declare that the subject matter of the dissertation entitled ‘Numbers in Bengali language’ is the record of the work done by me. -

On the Basis of Celebrated Festivals in Guwahati PJAEE, 17 (7) (2020)

Tradition and Transformation: On the basis of Celebrated Festivals in Guwahati PJAEE, 17 (7) (2020) Tradition and Transformation: On the basis of Celebrated Festivals in Guwahati Tutumoni Das Department of Assamese, Gauhati University, Guwahati, Assam, India Email: [email protected] Tutumoni Das: Tradition and Transformation: On the basis of Celebrated Festivals in Guwahati -- Palarch’s Journal Of Archaeology Of Egypt/Egyptology 17(7). ISSN 1567- 214x Keywords: Tradition, Transformation, Festival celebrated in Guwahati ABSTRACT Human’s trained and proficient works give birth to a culture. The national image of a nation emerges through culture. In the beginning people used to express their joy of farming by singing and dancing. The ceremony of religious conduct was set up at the ceremony of these. In the course of such festivals that were prevalent among the people, folk cultures were converted into festivals. These folk festivals are traditionally celebrated in the human society. Traditionally celebrated festivals take the national form as soon as they get status of formality. In the same territory, the appearance of the festival sits different from time to time. The various festivals that have traditionally come into being under the controls of change are now seen taking under look. Especially in the city of Guwahati in the state of Assam, various festivals do not have the traditional rituals but are replaced by modernity. As a result, many festivals are celebrated under the concept of to observe. Therefore, our research paper focuses on this issue and tries to analyze in the festival celebrated in Guwahati. 1. Introduction A festival means delight, being gained and an artistic creation. -

Formation of the Heterogeneous Society in Western Assam (Goal Para)

CHAPTER- III Formation of the Heterogeneous Society in Western Assam (Goal para) Erstwhile Goalpara district of Western Assam has a unique socio-cultural heritage of its own, identified as Goalpariya Society and Culture. The society is a heterogenic in character, composed of diverse racial, ethnic, religious and cultural groups. The medieval society that had developed in Western Assam, particularly in Goalapra region was seriously influenced by the induction of new social elements during the British Rule. It caused the reshaping of the society to a fully heterogenic in character with distinctly emergence of new cultural heritage, inconsequence of the fusion of the diverse elements. Zamindars of Western Assam, as an important social group, played a very important role in the development of new society and cufture. In the course of their zamindary rule, they brought Bengali Hidus from West Bengal for employment in zamindary service, Muslim agricultural labourers from East Bengal for extension of agricultural field, and other Hindusthani people for the purpose of military and other services. Most of them were allowed to settle in their respective estates, resulting in the increase of the population in their estate as well as in Assam. Besides, most of the zamindars entered in the matrimonial relations with the land lords of Bengal. As a result, we find great influence of the Bengali language and culture on this region. In the subsequent year, Bengali cultivators, business community of Bengal and Punjab and workers and labourers from other parts of Indian subcontinent, migrated in large number to Assam and settled down in different places including town, Bazar and waste land and char areas. -

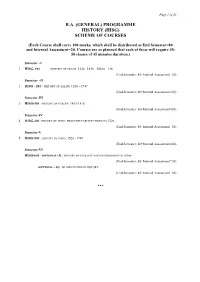

The Proposed New Syllabus of History for the B

Page 1 of 45 B.A. (GENERAL) PROGRAMME HISTORY (HISG) SCHEME OF COURSES (Each Course shall carry 100 marks, which shall be distributed as End Semester=80 and Internal Assessment=20. Courses are so planned that each of these will require 45- 50 classes of 45 minutes duration.) Semester –I 1. HISG- 101 : HISTORY OF ASSAM: 1228 –1826 – Marks= 100 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester –II 2. HISG - 201 : HISTORY OF ASSAM: 1826 – 1947 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester-III 3. HISG-301 : HISTORY OF EUROPE: 1453-1815 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester-IV 4. HISG-401: HISTORY OF INDIA FROM THE EARLIEST TIMES TO 1526 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester-V 5. HISG-501 : HISTORY OF INDIA: 1526 - 1947 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester-VI HISG-601 : (OPTIONAL - I) : HISTORY OF ECOLOGY AND ENVIRONMENT IN INDIA (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) (OPTIONAL – II) : WOMEN IN INDIAN HISTORY (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) *** Page 2 of 45 HISG – 101 End- Semester Marks : 80 In- Semester Marks : 20 HISTORY OF ASSAM: 1228 –1826 Total Marks : 100 10 to 12 classes per unit Objective: The objective of this paper is to give a general outline of the history of Assam from the 13th century to the occupation of Assam by the English East India Company in the first quarter of the 19th century. It aims to acquaint the students with the major stages of developments in the political, social and cultural history of the state during the medieval times. Unit-1: Marks: 16 1.01 : Sources- archaeological, epigraphic, literary, numismatic and accounts of the foreign travelers 1.02 : Political conditions of the Brahmaputra valley at the time of foundation of the Ahom kingdom. -

Women Education in Colonial Assam As Reflected in Contemporary Archival and Literary Records Chiranjib Dahal

SSRG International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Volume 8 Issue 3, 80-86, May-June, 2021 ISSN: 2394 – 2703 /doi:10.14445/23942703/IJHSS-V8I3P112 © 2021 Seventh Sense Research Group® Women Education in Colonial Assam as Reflected In Contemporary Archival And Literary Records Chiranjib Dahal Assistant Professor, Department of History, J.D.S.G. College, Bokakhat Dist.: Golaghat, State: Assam, Country: India 785612 Received Date: 15 May 2021 Revised Date: 21 June 2021 Accepted Date: 03 July 2021 Abstract - The present paper makes an attempt to trace the which can be inferred from literacy rate from 0.2 % in genesis and development of women’s education in colonial 1882 to 6% only in 1947(Kochhar,2009:225). It reveals Assam and its contribution to their changing status and that for centuries higher education for women has been aspirations. The contribution of the native elites in the neglected and the report University Education Commission process of the development of women education; and 1948 exposed that they were against women education. In social perception towards women education as reflected in their recommendation they wrote “women’s present the contemporary periodicals are some other areas of this education is entirely irrelevant to the life they have to lead. study. Educational development in Assam during the It is not only a waste but often a definite disability” colonial rule has generally been viewed by educational (University Education Commission Report, Government of historians to be the work of British rulers who introduced India, 1948-49). Educational development in Assam a system of education with the hidden agenda of initiating during the colonial rule has generally been viewed by a process of socialization. -

![July 28, 2003 [For Information of Members Only] Not to Be Reproduced Or Publicised to ALL MEMBERS NOTIFICATION NO. 721 PART](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3325/july-28-2003-for-information-of-members-only-not-to-be-reproduced-or-publicised-to-all-members-notification-no-721-part-773325.webp)

July 28, 2003 [For Information of Members Only] Not to Be Reproduced Or Publicised to ALL MEMBERS NOTIFICATION NO. 721 PART

July 28, 2003 [For information of members only] Not to be reproduced or publicised To ALL MEMBERS NOTIFICATION NO. 721 PART - I (a) CIRCULATION FIGURES - JULY/DECEMBER 2002 Circulation figures in respect of following two publications were certified after the release of Serial Volume No. 108 (July/December 2002) are notified hereunder, for information. Sr. Member- Previous PUBLICATION Average Average Increase Free No. ship No. Audit Net Paid Trade or Copies Period Circulation Terms Decrease Jan-Jun Jul-Dec Over Past 2002 2002 Period% DAILIES ENGLISH 1. 23-C Deemed The New Indian Express, 222,080 27.9 - 2,647 Not Bangalore edn. & also Received printed at Mangalore, Belgaum, Bhubaneswar, Chennai, Coimbatore, Hyderabad, Kochi, Kozhikode, Madurai, Shimoga, Thiruvananthapuram Vijayawadab &Vishakapatnam edns WEEKLIES ENGLISH 2. 1597 Deemed The New Sunday Express, 258,522 26.2 - 2,672 Not Hyderabad, Vijayawada, Received Visakhapatnam, Coimbatore, Belgaum, Shimoga, Kochi, Kozhikode, Trivandrum, Bhubaneswar, Chennai, Madurai & Bangalore edn. & also printed at Mangalore (b) SURPRISE-RECHECK AUDIT - JULY/DECEMBER 2002 In case of `Cricket Bharati' & `Madhur Kathayen' (Hindi Monthlies), New Delhi, Bureau Auditors had expressed inability to certify circulation figures for the period of Surprise-Recheck Audit i.e. July/December 2002. These were accordingly treated as `Not Accepted' and filed. PART - II PROGRESS OF MEMBERSHIP A) NEW MEMBERS I - PUBLISHERS Mangalam Publications (I) Pvt. in respect "MANGALAM" (Malayalam Ltd., Kottayam of Daily), Kottayam II - ADVERTISING AGENCIES 1) Cornerstone Communications Pvt. Ltd., Mumbai 2) Ind Advertising, Mumbai B) CESSATION UNDER ARTICLE 44(B) (for non-payment of membership fee) I - ADVERTISER TTK Prestige Limited, Bangalore II - ADVERTISING AGENCY Akshar Advtg. -

Marginalisation, Revolt and Adaptation: on Changing the Mayamara Tradition*

Journal of Ethnology and Folkloristics 15 (1): 85–102 DOI: 10.2478/jef-2021-0006 MARGINALISATION, REVOLT AND ADAPTATION: ON CHANGING THE MAYAMARA TRADITION* BABURAM SAIKIA PhD Student Department of Estonian and Comparative Folklore University of Tartu Ülikooli 16, 51003, Tartu, Estonia e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT Assam is a land of complex history and folklore situated in North East India where religious beliefs, both institutional and vernacular, are part and parcel of lived folk cultures. Amid the domination and growth of Goddess worshiping cults (sakta) in Assam, the sattra unit of religious and socio-cultural institutions came into being as a result of the neo-Vaishnava movement led by Sankaradeva (1449–1568) and his chief disciple Madhavadeva (1489–1596). Kalasamhati is one among the four basic religious sects of the sattras, spread mainly among the subdued communi- ties in Assam. Mayamara could be considered a subsect under Kalasamhati. Ani- ruddhadeva (1553–1626) preached the Mayamara doctrine among his devotees on the north bank of the Brahmaputra river. Later his inclusive religious behaviour and magical skill influenced many locals to convert to the Mayamara faith. Ritu- alistic features are a very significant part of Mayamara devotee’s lives. Among the locals there are some narrative variations and disputes about stories and terminol- ogies of the tradition. Adaptations of religious elements in their faith from Indig- enous sources have led to the question of their recognition in the mainstream neo- Vaishnava order. In the context of Mayamara tradition, the connection between folklore and history is very much intertwined. Therefore, this paper focuses on marginalisation, revolt in the community and narrative interpretation on the basis of folkloristic and historical groundings. -

The Protection of Human Rights of Rohingya in Myanmar: the Role of the International Community

Department of Political Science Master in International Relations Chair of: International Organization and Human Rights The Protection of Human Rights of Rohingya in Myanmar: The Role of The International Community CANDIDATE: SUPERVISOR: Riccardo Marzoli Professor Roberto Virzo No. 623322 CO-SUPERVISOR: Professor Francesco Cherubini Academic year: 2014/2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ………………………………………………………………………...p.5 1.THE PAST: THE HISTORICAL PRESENCE OF ROHINGYA IN RAKHINE STATE. SINCE THE ORIGINS TO 1978…………………………………………………………. 9 1.1.REWRITING HISTORY: CONFLICTING VERSIONS OF BURMESE AND INTERNATIONAL SCHOLARS ………………………………………………………. 10 1.1.1 ETIMOLOGY OF THE TERMS…………………………………………………………………. 13 1.2. ANCIENT HISTORY OF ARAKAN AND FIRST ISLAMIC CONTACTS……… 14 1.3 CHANDRAS DINASTY AND THE ORIGINS OF THE MAGHS…………………16 1.4. MIN SAW MUN AND THE ARAKANESE KINGS WITH MUSLIM TITLES: THE SIGN OF A WIDESPREAD ISLAMIC INFLUENCE……………………………………...17 1.4.1 DIFFERENT VISIONS: WHICH ROLE FOR ROHINGYA IN MYANMAR?...................19 1.5 A NEW INFLUX: FRATRICIDAL WARS BETWEEN THE HEIRS OF THE MUGHALS’ THRONE AND THE ROLE OF THE KAMANS……………………………20 1.6 DIFFERENT WAVES OF MUSLIM ENTRANCES TO ARAKAN………………...21 1.7 1781 THE ADVENT OF THE BURMANS. THE OCCUPATION BY BODAW PAYA AND THE PREMISES OF THE BRITISH DOMINANCE ………………………………..24 1.7.1 KING SANDA WIZAYA AND THE KAMANS IN RAMREE………………………………...24 1.7.2 THE END OF THE KINGDOM OF MRAUK-U AND THE ARRIVAL OF THE AVA ARMY……………………………………………………………………………………………………………….25 1.7.3 KING BERING’S SAGA AND THE ARAKANESE -

Cosmopolitan Consciousness of PC Barua

E-CineIndia: Jan-Mar 2021/ Parthajit Baruah 1 Article Parthajit Baruah The Question of Assameseness: Cosmopolitan Consciousness of P.C. Barua Still from Barua’s film Mukti An extensive discussion has been made on the made Devdas in three Languages - Bengali (1935), biographical sketch and works of Pramathesh Hindi (1936) and Assamese (1937). Likewise, World Chandra Barua, one of the leading pioneers of India Heritage Encyclopedia, cinema. But the aspect that has hardly been found a bollywoodirect.medium.com, amp.blog.shops- space in the writing and discussion at the national net.com and numerous sources carry the same narrative is why Pramathesh, being an ardent lover of incorrect information stating that Assamese Devdas Gauripur, Assam, did not make an Assamese film in made in 1937 was Barua’s last of the three language the span of two decades of his cinematic journey. versions of the film. Wikipedia misleadingly Displeasures across the state of Assam in the 1940s mentions that Bhupen Hazarika was the playback was seen, and many termed Barua as ‘anti nationalist’ singer of the film. It is pertinent to mention here that in Assam. Ibha Barua Datta, scion of the Barua when Jyoti Chitraban film studio was established in family, says that she is disheartened to read the sharp Guwahati and became functional from 1968, Dr. criticism on Pramathesh in the Assamese newspapers Hazarika proposed the Government of Assam to for not making an Assamese film. name the studio’s shooting floor after Pramathesh Ch. Barua. Bhadari by Nip Baruah was the first film, shot Some erroneously claim that Barua made three at Pramathesh Ch. -

Event, Memory and Lore: Anecdotal History of Partition in Assam

ISSN. 0972 - 8406 61 The NEHU Journal, Vol XII, No. 2, July - December 2014, pp. 61-76 Event, Memory and Lore: Anecdotal History of Partition in Assam BINAYAK DUTTA * Abstract Political history of Partition of India in 1947 is well-documented by historians. However, the grass root politics and and the ‘victim- hood’ of a number of communities affected by the Partition are still not fully explored. The scholarly moves to write alternative History based on individual memory and family experience, aided by the technological revolution have opened up multiple narratives of the partition of Assam and its aftermath. Here in northeast India the Partition is not just a History, but a lived story, which registers its presence in contemporary politics through songs, poems, rhymes and anecdotes related to transfer of power in Assam. These have remained hidden from mainstream partition scholarship. This paper seeks to attempt an anecdotal history of the partition in Assam and the Sylhet Referendum, which was a part of this Partition process . Keywords : sylhet, partition, referendum, muslim league, congress. Introduction HVSLWHWKHSDVVDJHRIPRUHWKDQVL[W\¿YH\HDUVVLQFHWKHSDUWLWLRQ of India, the politics that Partition generated continues to be Dalive in Assam even today. Although the partition continues to be relevant to Assam to this day, it remains a marginally researched area within India’s Partition historiography. In recent years there have been some attempts to engage with it 1, but the study of the Sylhet Referendum, the event around which partition in Assam was constructed, has primarily been treated from the perspective of political history and refugee studies. 2 ,W LV WLPH +LVWRU\ ZULWLQJ PRYHG EH\RQG WKH FRQ¿QHV RI political history. -

Media Accreditation Index

LOK SABHA PRESS GALLERY PASSES ISSUED TO ACCREDITED MEDIA PERSONS - 2020 Sl.No. Name Agency / Organisation Name 1. Ashok Singhal Aaj Tak 2. Manjeet Singh Negi Aaj Tak 3. Rajib Chakraborty Aajkaal 4. M Krishna ABN Andhrajyoti TV 5. Ashish Kumar Singh ABP News 6. Pranay Upadhyaya ABP News 7. Prashant ABP News 8. Jagmohan Singh AIR (B) 9. Manohar Singh Rawat AIR (B) 10. Pankaj Pati Pathak AIR (B) 11. Pramod Kumar AIR (B) 12. Puneet Bhardwaj AIR (B) 13. Rashmi Kukreti AIR (B) 14. Anand Kumar AIR (News) 15. Anupam Mishra AIR (News) 16. Diwakar AIR (News) 17. Ira Joshi AIR (News) 18. M Naseem Naqvi AIR (News) 19. Mattu J P Singh AIR (News) 20. Souvagya Kumar Kar AIR (News) 21. Sanjay Rai Aj 22. Ram Narayan Mohapatra Ajikali 23. Andalib Akhter Akhbar-e-Mashriq 24. Hemant Rastogi Amar Ujala 25. Himanshu Kumar Mishra Amar Ujala 26. Vinod Agnihotri Amar Ujala 27. Dinesh Sharma Amrit Prabhat 28. Agni Roy Ananda Bazar Patrika 29. Diganta Bandopadhyay Ananda Bazar Patrika 30. Anamitra Sengupta Ananda Bazar Patrika 31. Naveen Kapoor ANI 32. Sanjiv Prakash ANI 33. Surinder Kapoor ANI 34. Animesh Singh Asian Age 35. Prasanth P R Asianet News 36. Asish Gupta Asomiya Pratidin 37. Kalyan Barooah Assam Tribune 38. Murshid Karim Bandematram 39. Samriddha Dutta Bartaman 40. Sandip Swarnakar Bartaman 41. K R Srivats Business Line 42. Shishir Sinha Business Line 43. Vijay Kumar Cartographic News Service 44. Shahid K Abbas Cogencis 45. Upma Dagga Parth Daily Ajit 46. Jagjit Singh Dardi Daily Charhdikala 47. B S Luthra Daily Educator 48.