Identity and Violence in India's North East: Towards a New Paradigm

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyright by Abikal Borah 2015

Copyright By Abikal Borah 2015 The Report committee for Abikal Borah certifies that this is the approved version of the following report: A Region in a Mobile World: Integration of Southeastern sub-Himalayan Region into the Global Capitalist Economy (1820-1900) Supervisor: ________________________________________ Mark Metzler ________________________________________ James M. Vaughn A Region in a Mobile World: Integration of Southeastern sub-Himalayan Region into the Global Capitalist Economy (1820-1900) By Abikal Borah, M. Phil Report Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in partial fulfillment of the degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin December, 2015 A Region in a Mobile World: Integration of Southeastern sub-Himalayan Region into the Global Capitalist Economy (1820-1900) By Abikal Borah, M.A. University of Texas at Austin, 2015 Supervisor: Mark Metzler Abstract: This essay considers the history of two commodities, tea in Georgian England and opium in imperial China, with the objective of explaining the connected histories in the Eurasian landmass. It suggests that an exploration of connected histories in the Eurasian landmass can adequately explain the process of integration of southeastern sub-Himalayan region into the global capitalist economy. In doing so, it also brings the historiography of so called “South Asia” and “East Asia” into a dialogue and opens a way to interrogate the narrow historiographical visions produced from area studies lenses. Furthermore, the essay revisits a debate in South Asian historiography that was primarily intended to reject Immanuel Wallerstein’s world system theory. While explaining the historical differences of southeastern sub-Himalayan region with peninsular India, Bengal, and northern India, this essay problematizes the South Asianists’ critiques of Wallerstein’s conceptual model. -

The Bodo Movement: Past and Present

© 2019 JETIR June 2019, Volume 6, Issue 6 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) THE BODO MOVEMENT: PAST AND PRESENT Berlao K. Karjie Research Scholar Dept. of Political Science Bodoland University INTRODUCTION The Boro or Bodo or Kachari is the earliest known inhabitant of Assam. The Bodos belong to racial origin of Mongoloid group. The Mongoloid population over time had formed a solid bloc spreading throughout the Brahmaputra and Barak valleys stretching to Cachar Hills of Assam, Meghalaya, and Tripura extending to some parts of West Bengal, Bihar, Nepal, Bhutan and Bangladesh with different identities. The Boro, Borok (Tripuri), Garo, Dimasa, Rabha, Chutiya, Tiwa, Sarania, Moholia, Kachari, Deuri, Borahi, Modahi, Sonowal, Thengal, Dhimal, Koch, Mech, Meche, Barman, Moran, Hajong, Rhamsa are historically, racially and linguistically of same ancestry. Since the historically untraced ages, the Bodo had exercised their highly developed political, legal and socio-cultural influences. Today the majority of Bodos are found concentrated in the foot hills of the Himalayan ranges in the north bank of the Brahmaputra valley. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND OF THE BODO NATION The Bodos had a glorious past history which is found mentioned in Hindu mythology like Vedic literature and epic like Mahabharata, Ramayana and Puranas with different derogatory names like Ausura, Mlecha and Kirata dynasty. The Bodos had once ruled the entire part of Himalayan ranges extending to Brahmaputra valley with different names and dynasties. For the first time in the recorded history the Ahoms attacked and invaded their country in the early part of the 13th century which continued almost 200 years. Despite of many external invasions the Bodos lived as a free nation with dignity and honour till the British invaded their dominions. -

Numbers in Bengali Language

NUMBERS IN BENGALI LANGUAGE A dissertation submitted to Assam University, Silchar in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Masters of Arts in Department of Linguistics. Roll - 011818 No - 2083100012 Registration No 03-120032252 DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS SCHOOL OF LANGUAGE ASSAM UNIVERSITY SILCHAR 788011, INDIA YEAR OF SUBMISSION : 2020 CONTENTS Title Page no. Certificate 1 Declaration by the candidate 2 Acknowledgement 3 Chapter 1: INTRODUCTION 1.1.0 A rapid sketch on Assam 4 1.2.0 Etymology of “Assam” 4 Geographical Location 4-5 State symbols 5 Bengali language and scripts 5-6 Religion 6-9 Culture 9 Festival 9 Food havits 10 Dresses and Ornaments 10-12 Music and Instruments 12-14 Chapter 2: REVIEW OF LITERATURE 15-16 Chapter 3: OBJECTIVES AND METHODOLOGY Objectives 16 Methodology and Sources of Data 16 Chapter 4: NUMBERS 18-20 Chapter 5: CONCLUSION 21 BIBLIOGRAPHY 22 CERTIFICATE DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS SCHOOL OF LANGUAGES ASSAM UNIVERSITY SILCHAR DATE: 15-05-2020 Certified that the dissertation/project entitled “Numbers in Bengali Language” submitted by Roll - 011818 No - 2083100012 Registration No 03-120032252 of 2018-2019 for Master degree in Linguistics in Assam University, Silchar. It is further certified that the candidate has complied with all the formalities as per the requirements of Assam University . I recommend that the dissertation may be placed before examiners for consideration of award of the degree of this university. 5.10.2020 (Asst. Professor Paramita Purkait) Name & Signature of the Supervisor Department of Linguistics Assam University, Silchar 1 DECLARATION I hereby Roll - 011818 No - 2083100012 Registration No – 03-120032252 hereby declare that the subject matter of the dissertation entitled ‘Numbers in Bengali language’ is the record of the work done by me. -

On the Basis of Celebrated Festivals in Guwahati PJAEE, 17 (7) (2020)

Tradition and Transformation: On the basis of Celebrated Festivals in Guwahati PJAEE, 17 (7) (2020) Tradition and Transformation: On the basis of Celebrated Festivals in Guwahati Tutumoni Das Department of Assamese, Gauhati University, Guwahati, Assam, India Email: [email protected] Tutumoni Das: Tradition and Transformation: On the basis of Celebrated Festivals in Guwahati -- Palarch’s Journal Of Archaeology Of Egypt/Egyptology 17(7). ISSN 1567- 214x Keywords: Tradition, Transformation, Festival celebrated in Guwahati ABSTRACT Human’s trained and proficient works give birth to a culture. The national image of a nation emerges through culture. In the beginning people used to express their joy of farming by singing and dancing. The ceremony of religious conduct was set up at the ceremony of these. In the course of such festivals that were prevalent among the people, folk cultures were converted into festivals. These folk festivals are traditionally celebrated in the human society. Traditionally celebrated festivals take the national form as soon as they get status of formality. In the same territory, the appearance of the festival sits different from time to time. The various festivals that have traditionally come into being under the controls of change are now seen taking under look. Especially in the city of Guwahati in the state of Assam, various festivals do not have the traditional rituals but are replaced by modernity. As a result, many festivals are celebrated under the concept of to observe. Therefore, our research paper focuses on this issue and tries to analyze in the festival celebrated in Guwahati. 1. Introduction A festival means delight, being gained and an artistic creation. -

Uhm Phd 9519439 R.Pdf

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality or the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely. event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. MI48106·1346 USA 313!761-47oo 800:521-0600 Order Number 9519439 Discourses ofcultural identity in divided Bengal Dhar, Subrata Shankar, Ph.D. University of Hawaii, 1994 U·M·I 300N. ZeebRd. AnnArbor,MI48106 DISCOURSES OF CULTURAL IDENTITY IN DIVIDED BENGAL A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN POLITICAL SCIENCE DECEMBER 1994 By Subrata S. -

Votes, Voters and Voter Lists: the Electoral Rolls in Barak Valley, Assam

SHABNAM SURITA | 83 Votes, Voters and Voter Lists: The Electoral Rolls in Barak Valley, Assam Shabnam Surita Abstract: Electoral rolls, or voter lists, as they are popularly called, are an integral part of the democratic setup of the Indian state. Along with their role in the electoral process, these lists have surfaced in the politics of Assam time and again. Especially since the 1970s, claims of non-citizens becoming enlisted voters, incorrect voter lists and the phenomenon of a ‘clean’ voter list have dominated electoral politics in Assam. The institutional acknowledgement of these issues culminated in the Assam Accord of 1985, establishing the Asom Gana Parishad (AGP), a political party founded with the goal of ‘cleaning up’ the electoral rolls ‘polluted with foreign nationals’. Moreo- ver, the Assam Agitation, between 1979 and 1985, changed the public discourse on the validity of electoral rolls and turned the rolls into a major focus of political con- testation; this resulted in new terms of citizenship being set. However, following this shift, a prolonged era of politicisation of these rolls continued which has lasted to this day. Recently, discussions around the electoral rolls have come to popular and academic attention in light of the updating of the National Register of Citizens and the Citizenship Amendment Act. With the updating of the Register, the goal was to achieve a fair register of voters (or citizens) without outsiders. On the other hand, the Act seeks to modify the notion of Indian citizenship with respect to specific reli- gious identities, thereby legitimising exclusion. As of now, both the processes remain on functionally unclear and stagnant grounds, but the process of using electoral rolls as a tool for both electoral gain and the organised exclusion of a section of the pop- ulation continues to haunt popular perceptions. -

6.Hum-RECEPTION and TRANSLATION of INDIAN

IMPACT: International Journal of Research in Humanities, Arts and Literature (IMPACT: IJRHAL) ISSN(E): 2321-8878; ISSN(P): 2347-4564 Vol. 3, Issue 12, Dec 2015, 53-58 © Impact Journals RECEPTION AND TRANSLATION OF INDIAN LITERATURE INTO BORO AND ITS IMPACT IN THE BORO SOCIETY PHUKAN CH. BASUMATARY Associate Professor, Department of Bodo, Bodoland University, Kokrajhar, Assam, India ABSTRACT Reception is an enthusiastic state of mind which results a positive context for diffusing cultural elements and features; even it happens knowingly or unknowingly due to mutual contact in multicultural context. It is worth to mention that the process of translation of literary works or literary genres done from one language to other has a wide range of impact in transmission of culture and its value. On the one hand it helps to bridge mutual intelligibility among the linguistic communities; and furthermore in building social harmony. Keeping in view towards the sociological importance and academic value translation is now-a-day becoming major discipline in the study of comparative literature as well as cultural and literary relations. From this perspective translation is not only a means of transference of text or knowledge from one language to other; but an effective tool for creating a situation of discourse among the cultural surroundings. In this brief discussion basically three major issues have been taken into account. These are (i) situation and reason of welcoming Indian literature and (ii) the process of translation of Indian literature into Boro and (iii) its impact in the society in adaption of translation works. KEYWORDS: Reception, Translation, Transmission of Culture, Discourse, Social Harmony, Impact INTRODUCTION The Boro language is now-a-day a scheduled language recognized by the Government of India in 2003. -

Survey of Conflicts & Resolution in India's Northeast

Survey of Conflicts & Resolution in India’s Northeast? Ajai Sahni? India’s Northeast is the location of the earliest and longest lasting insurgency in the country, in Nagaland, where separatist violence commenced in 1952, as well as of a multiplicity of more recent conflicts that have proliferated, especially since the late 1970s. Every State in the region is currently affected by insurgent and terrorist violence,1 and four of these – Assam, Manipur, Nagaland and Tripura – witness scales of conflict that can be categorised as low intensity wars, defined as conflicts in which fatalities are over 100 but less than 1000 per annum. While there ? This Survey is based on research carried out under the Institute’s project on “Planning for Development and Security in India’s Northeast”, supported by the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA). It draws on a variety of sources, including Institute for Conflict Management – South Asia Terrorism Portal data and analysis, and specific State Reports from Wasbir Hussain (Assam); Pradeep Phanjoubam (Manipur) and Sekhar Datta (Tripura). ? Dr. Ajai Sahni is Executive Director, Institute for Conflict Management (ICM) and Executive Editor, Faultlines: Writings on Conflict and Resolution. 1 Within the context of conflicts in the Northeast, it is not useful to narrowly define ‘insurgency’ or ‘terrorism’, as anti-state groups in the region mix in a wide range of patterns of violence that target both the state’s agencies as well as civilians. Such violence, moreover, meshes indistinguishably with a wide range of purely criminal actions, including drug-running and abduction on an organised scale. Both the terms – terrorism and insurgency – are, consequently, used in this paper, as neither is sufficient or accurate on its own. -

The Proposed New Syllabus of History for the B

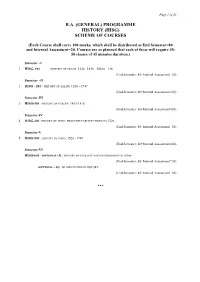

Page 1 of 45 B.A. (GENERAL) PROGRAMME HISTORY (HISG) SCHEME OF COURSES (Each Course shall carry 100 marks, which shall be distributed as End Semester=80 and Internal Assessment=20. Courses are so planned that each of these will require 45- 50 classes of 45 minutes duration.) Semester –I 1. HISG- 101 : HISTORY OF ASSAM: 1228 –1826 – Marks= 100 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester –II 2. HISG - 201 : HISTORY OF ASSAM: 1826 – 1947 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester-III 3. HISG-301 : HISTORY OF EUROPE: 1453-1815 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester-IV 4. HISG-401: HISTORY OF INDIA FROM THE EARLIEST TIMES TO 1526 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester-V 5. HISG-501 : HISTORY OF INDIA: 1526 - 1947 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester-VI HISG-601 : (OPTIONAL - I) : HISTORY OF ECOLOGY AND ENVIRONMENT IN INDIA (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) (OPTIONAL – II) : WOMEN IN INDIAN HISTORY (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) *** Page 2 of 45 HISG – 101 End- Semester Marks : 80 In- Semester Marks : 20 HISTORY OF ASSAM: 1228 –1826 Total Marks : 100 10 to 12 classes per unit Objective: The objective of this paper is to give a general outline of the history of Assam from the 13th century to the occupation of Assam by the English East India Company in the first quarter of the 19th century. It aims to acquaint the students with the major stages of developments in the political, social and cultural history of the state during the medieval times. Unit-1: Marks: 16 1.01 : Sources- archaeological, epigraphic, literary, numismatic and accounts of the foreign travelers 1.02 : Political conditions of the Brahmaputra valley at the time of foundation of the Ahom kingdom. -

The East India Company: Agent of Empire in the Early Modern Capitalist Era

Social Education 77(2), pp 78–81, 98 ©2013 National Council for the Social Studies The Economics of World History The East India Company: Agent of Empire in the Early Modern Capitalist Era Bruce Brunton The world economy and political map changed dramatically between the seventeenth 2. Second, while the government ini- and nineteenth centuries. Unprecedented trade linked the continents together and tially neither held ownership shares set off a European scramble to discover new resources and markets. European ships nor directed the EIC’s activities, it and merchants reached across the world, and their governments followed after them, still exercised substantial indirect inaugurating the modern eras of imperialism and colonialism. influence over its success. Beyond using military and foreign policies Merchant trading companies, exem- soon thereafter known as the East India to positively alter the global trading plified by the English East India Company (EIC), which gave the mer- environment, the government indi- Company, were the agents of empire chants a monopoly on all trade east of rectly influenced the EIC through at the dawn of early modern capital- the Cape of Good Hope for 15 years. its regularly exercised prerogative ism. The East India Company was a Several aspects of this arrangement to evaluate and renew the charter. monopoly trading company that linked are worth noting: Understanding the tension in this the Eastern and Western worlds.1 While privilege granting-receiving relation- it was one of a number of similar compa- 1. First, the EIC was a joint-stock ship explains much of the history of nies, both of British origin (such as the company, owned and operated by the EIC. -

Sanskritisation of Bengali, Plight of the Margin and the Forgotten Role of Tagore

Journal of the Department of English Vidyasagar University Vol. 11, 2013-2014 Sanskritisation of Bengali, Plight of the Margin and the Forgotten Role of Tagore Sandipan Sen It is well known that, after the victory of Lord Clive against Sirajuddaula at the battle of Plassey in 1757, there was an unprecedented reign of loot in Bengal, as the British presided over a drainage of wealth from Bengal. According to one estimate, apart from the “official compensation” to the British army and navy, the members of the Council of the British East India Company received an amount of L 50,000 to L 80,000 each, and Clive alone took away L 234,000 over and above a jaigir worth L 30,000 a year (Smith 473). This apart, most British men carried out a grand loot at individual levels, the extent of which is difficult to imagine. The magnitude of the loot can be estimated from the fact that Govind Chand, the descendant of Mahatab Chand - the Jagat Seth during the battle of Plassey who had a staggering annual income of Rs 26,800,000 in 1765 - was reduced to penury as a result of the loot, and the British rulers granted him a monthly dole of Rs 1200 (Sikdar 986). Needless to say, this grand loot completely destroyed the economic structure of Bengal, which was a prosperous and wealthy kingdom. However, it often eludes our attention that the arrival of the British not only destroyed the economy of Bengal, but also the language of Bengal, i.e. the Bengali language. -

Exploration of Portuguese-Bengal Cultural Heritage Through Museological Studies

Exploration of Portuguese-Bengal Cultural Heritage through Museological Studies Dr. Dhriti Ray Department of Museology, University of Calcutta, Kolkata, West Bengal, India Line of Presentation Part I • Brief history of Portuguese in Bengal • Portuguese-Bengal cultural interactions • Present day continuity • A Gap Part II • University of Calcutta • Department of Museology • Museological Studies/Researches • Way Forwards Portuguese and Bengal Brief History • The Portuguese as first European explorer to visit in Bengal was Joao da Silveira in 1518 , couple of decades later of the arrival of Vasco Da Gama at Calicut in 1498. • Bengal was the important area for sugar, saltpeter, indigo and cotton textiles •Portuguese traders began to frequent Bengal for trading and to aid the reigning Nawab of Bengal against an invader, Sher Khan. • A Portuguese captain Tavarez received by Akbar, and granted permission to choose any spot in Bengal to establish trading post. Portuguese settlements in Bengal In Bengal Portuguese had three main trade points • Saptagram: Porto Pequeno or Little Haven • Chittagong: Porto Grande or Great Haven. • Hooghly or Bandel: In 1599 Portuguese constructed a Church of the Basilica of the Holy Rosary, commonly known as Bandel Church. Till today it stands as a memorial to the Portuguese settlement in Bengal. The Moghuls eventually subdued the Portuguese and conquered Chittagong and Hooghly. By the 18th century the Portuguese presence had almost disappeared from Bengal. Portuguese settlements in Bengal Portuguese remains in Bengal • Now, in Bengal there are only a few physical vestiges of the Portuguese presence, a few churches and some ruins. But the Portuguese influence lives on Bengal in other ways— • Few descendents of Luso-Indians (descendants of the offspring of mixed unions between Portuguese and local women) and descendants of Christian converts are living in present Bengal.