Survey of Conflicts & Resolution in India's Northeast

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To 31.12.2015 to Gram Vikas

F. No: SW-45/3/20 I 5-SWADHAR Govelnment of India Ministry of Wornen and Chitd Developrnent Shastri Biralvan, I.Jew Deihi Dated: 16.A1.2A17 . To, The Pay and Accounts Officer Ministry of Women and Child Development Shastri Bhavan; New Delhi Subject: - Reimbursement of the Grant for the period 1.04.2014 to 31.L2.2A15 to Gram Vikas (Voluntary Organization), H.No.l6-3TlI,.Vidyanagar Road, Sathupaliy, Khammam District, Telangana-507303 for running Swadhar Shelter Home & Women Helpline under Swadhar Scheme. Sir/Madam, ln continuation of this Ministry's Sanction order of even number dated 19.06.2015. I am directed toconvey the sanction of tlre President of hidia to the payinent.of fts.13,72,298/- (Rupees Thirteer. lakh seventy two thousand two hundred and ninety eight only) for the period t.84.2:'Jl4 to 31.12.2015 to Gram Vikas (Voluntary Organizatiorr), Ftr.No.l6-3UL, Vidy*nagar lioad, Sathupally, Khammam District, Telangana-507303 for financial year 2016=2Al'7 for runniug __.: Swadhar Shelter home & Women helpline under Swadhar Scheme. The details of the projeci are as .follows: (a) Location of the Project: - At Plot No. 122, H,No. 3-5113 (new H.No. 24-1-65), Sath'.rpally, Khammam District, Telangana. (b) Number of beneficiaries: 38 womerr & 5 children (for 2014-15) & 3l r.vomen & 9 childieir (for 20 I 5- I 6) 2. The grant is subject to the following conditions: i. Before the amount is paid by an Account Payee Cheque, a ceftificate is to be furnished by tlre NGO stating that no funds have been received from any other source for the purpose for which this amount has been sauctioned. -

Sebuah Kajian Pustaka

International Journal of Research in Social Sciences Vol. 8 Issue 7, July 2018, ISSN: 2249-2496 Impact Factor: 7.081 Journal Homepage: http://www.ijmra.us, Email: [email protected] Double-Blind Peer Reviewed Refereed Open Access International Journal - Included in the International Serial Directories Indexed & Listed at: Ulrich's Periodicals Directory ©, U.S.A., Open J-Gage as well as in Cabell‟s Directories of Publishing Opportunities, U.S.A Conflicts in Northeast India: Intra-state conflicts with reference to Assam Dharitry Borah Debotosh Chakraborty Abstract Conflict in Northeast India has a brand entity that entrenched country‟s name in the world affairs for decades. In this paper, an attempt was made to study the genesis of conflicts in Northeast India with special emphasis on the intra-state conflicts in Assam. Attempts Keywords: were also made to highlight reasons why Northeast India has Conflict; remained to be a highly conflict ridden area comparing to other parts Sovereignty; of India. The findings revealed that the state has continued to be a Separate homeland; hub for several intra-state conflicts – as some particular groups raised Indian State demand for a sovereign state, while some others are betrothed in demanding for a separate state or homeland. There exists a strong nexus between historical circumstances and their intertwined influence on the contemporary conflict situations in the State. For these deep-rooted influences, critical suggestions are incorporated in order to deal with the conflicts and to bring sustainable and long- lasting peace in the State. Ph.D. Candidate, Department of Political Science, Assam University, Silchar, Assam, India Assistant Professor, Department of Political Science, Assam University, Silchar, Assam, India 715 International Journal of Research in Social Sciences http://www.ijmra.us, Email: [email protected] ISSN: 2249-2496Impact Factor: 7.081 1. -

District Census Handbook Senapati

DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK SENAPATI 1 DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK SENAPATI MANIPUR SENAPATI DISTRICT 5 0 5 10 D Kilometres er Riv ri a N b o A n r e K T v L i G R u z A d LAII A From e S ! r Dimapur ve ! R i To Chingai ako PUNANAMEI Dzu r 6 e KAYINU v RABUNAMEI 6 TUNGJOY i C R KALINAMEI ! k ! LIYAI KHULLEN o L MAO-MARAM SUB-DIVISION PAOMATA !6 i n TADUBI i rak River 6 R SHAJOUBA a Ba ! R L PUNANAMEIPAOMATA SUB-DIVISION N ! TA DU BI I MARAM CENTRE ! iver R PHUBA KHUMAN 6 ak ar 6 B T r MARAM BAZAR e PURUL ATONGBA v r i R ! e R v i i PURUL k R R a PURUL AKUTPA k d C o o L R ! g n o h k KATOMEI PURUL SUB-DIVISION A I CENTRE T 6 From Tamenglong G 6 TAPHOU NAGA P SENAPATI R 6 6 !MAKHRELUI TAPHOU KUKI 6 To UkhrulS TAPHOU PHYAMEI r e v i T INDIAR r l i e r I v i R r SH I e k v i o S R L g SADAR HILLS WEST i o n NH 2 a h r t I SUB-DIVISION I KANGPOKPI (C T) ! I D BOUNDARY, STATE......................................................... G R SADAR HILLS EAST KANGPOKPI SUB-DIVISION ,, DISTRICT................................................... r r e e D ,, v v i i SUB-DIVISION.......................................... R R l a k h o HEADQUARTERS: DISTRICT......................................... p L SH SAIKUL i P m I a h c I R ,, SUB-DIVISION................................ -

Proceedings of the 61St Meeting of North Eastern Council on 27Th June

FINAL PROCEEDINGS of the 61ST MEETING Of NORTH EASTERN COUNCIL (12TH Meeting as the Statutory Regional Planning Body for the NER) On 27TH JUNE, 2012 In the Main Committee Room, Parliament House Annexe, New Delhi North Eastern Council Secretariat Nongrim Hills, Shillong – 793003 I N D E X Agenda Items Contents Page No Address of Hon’ble Chairman, NEC 1 Agenda Item No. 1 Secretary presents his report 1 – 2 Agenda Item No. 2 Confirmation of the Proceedings of the 60th (Sixtieth) Meeting of the NEC held on 16th -17th June, 2011 at New 2 – 2 Delhi Agenda Item No. 3 Discussions on the Action Taken Report of the decisions of 2 – 5 the 60th Meeting of the NEC Agenda Item No. 4 Discussions on the draft 12th Five Year Plan (2012-17) and 5 – 9 the draft Annual Plan 2012-13 of the NEC Agenda Item No. 5 Presentation by Ministry of Railways on the Action Plan 10 – 19 prepared for North Eastern Region and discussions thereon. Agenda Item No. 6 Presentation by Ministry of Road Transport & Highways on 19 - 26 the Action Plan prepared for North Eastern Region and discussions thereon. Agenda Item No. 7 Presentation by Ministry of Civil Aviation on the Action Plan 26 – 45 prepared for North Eastern Region and discussions thereon. Annexure – I Address of the Hon’ble Chairman, NEC 46 – 51 Annexure – II Report of Secretary, NEC 52 – 80 Annexure – III Written Speeches of Their Excellencies the Governors and 81 – 223 Hon’ble Chief Ministers of NE States Annexure – IV List of Participants 224 - 226 PROCEEDINGS OF THE 61st NORTH EASTERN COUNCIL MEETING HELD ON 27th JUNE, 2012 AT THE PARLIAMENT HOUSE ANNEXE, NEW DELHI. -

Quest for Nagalim: Mapping of Perceptions Outside Nagaland

Quest for Nagalim: Mapping of Perceptions Outside Nagaland Pradeep Singh Chhonkar Introduction The Nagas of Nagaland could always identify themselves with the Naga identity due to being in a state named after their own collective identity. However, the Naga tribes outside Nagaland, especially those of Manipur and Assam, always had a strong reason to reassert their Naga-ness. The response to the idea of a separate Nagalim has been wide-ranging across the entire region affected by Naga insurgency. A Framework Agreement was signed between the Government of India and the National Socialist Council of Nagaland (NSCN-IM) on August 03, 2015. The agreement affected four states and approximately 35 Naga and other ethnic tribes inhabiting the traditional Naga areas. The agreement set three crucial parameters for the detailed settlement. First, it recognised that the Naga ‘history and situation’ was unique. Second, it proposed that sovereign powers would be shared between the Centre and the Nagas through a division of competencies, that is, through renegotiating the Union, State and Concurrent Lists of competencies of the Indian Constitution. Third, the two sides would strive for a mutually acceptable and peaceful settlement. While details of the accord are still shrouded in secrecy, it has been indicated that there will be no modification to the state boundaries. There Brigadier Pradeep Singh Chhonkar SM, VSM, is former Research Fellow at IDSA and presently commanding a Brigade in Northeast India. 80 CLAWS Journal l Winter 2018 QUEST FOR NAGALIM are indications about facilitation of cultural integration of the Nagas through special measures, and provision of financial and administrative autonomy of the Naga dominated areas in other states. -

Executive Summary DISTRICT PROFILE

Executive Summary 2011 -12 Chandel District having an area of 3313 sq. km, population of about 144028 ( 2011 census)with an international border of about half of the district boundary has a distinction of multi ethnic tribal inhabitants with a few pockets of Meiteis, Muslims, Nepalese, Biharies and other Indian nationals specially at Moreh areas. It is one of the backward hill districts of Manipur with inaccessible problem in many of the villages even on foot and its prevailing Law and Order situation at the border villages to Myanmar. The Integrated Health Action Plan (2013-14) provides information on the various importance subjects like RCH-II, New additionalities under NRHM, Routine Immunization Strengthening, Vertical Programmes through elaborate annexures. The Integrated District Health Action Plan (DHAP) of National Rural Health Mission was prepared with a vision to address local needs and specificities, enable decentralization and public participation, facilitate interdepartmental convergence and improve accountability of Health system. DISTRICT PROFILE The Chandel district is one of the important districts of the state given the multi-lingual, multi- ethnicity culture and tradition it possesses. The District lies in the south-eastern part of Manipur. It is the border district of the state. Its neighbors are Myanmar (erstwhile Burma) on the south, Ukhrul district on the east, Churachandpur district on the south and west, and Thoubal district on north. It is about 64 km. away from Imphal. Several communities inhabit the district and they are scattered all over the district. Prominent tribes in the district are Anal, Lamkang, Kukis, Moyon, Monsang, Chothe, Thadou, Paite, and Maring etc. -

Review of Research

Review Of ReseaRch impact factOR : 5.7631(Uif) UGc appROved JOURnal nO. 48514 issn: 2249-894X vOlUme - 8 | issUe - 7 | apRil - 2019 __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ AN ANALYSIS OF THE AUTONOMY MOVEMENT OF HILL TRIBES OF ASSAM Ishani Senapoti Research Scholar, Department of Political Science Gauhati University, Guwahati, Assam, India. ABSTRACT : Movements for Autonomy have marked the political discourse in Northeast India for the last decades. The aim and purpose of the autonomy movement is not only to bring about change in the existing system but also to augment legitimate expressions of aspirations by the people having a distinct culture, tradition and common pattern of living. In the post colonial period, Assam which is a land of diverse ethnic communities has witnessed a serious of autonomy movements based on the political demands for statehood. The autonomy movement of the Hill Tribals in North East India in general and North Cachar Hills District and Karbi Anglong District of Assam in particular is a continuous effort and struggle of the Hill Tribal to protect and preserve their distinct identity, culture and tradition and to bring about a change in the existing socio-political arrangement. Although the Sixth Schedule of the Indian Constitution has provided for Autonomous Councils in these two districts but much improvement could not be achieved due to limited power of the Autonomous District Council and the State government’s apathy. Their demand for an autonomous state is rooted in the long history of similar movements in the north east and has been demanding a separate state for the Dimasas and the Karbis in the name of ‘Dimaraji’ for Dimasas and ‘Hemprek’ for Karbis. -

Fee Collections for Miscellaneous Registration of Societies Under The

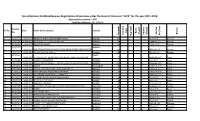

Fee collections for Miscellaneous Registration of Societies under the Head of Accounts "1475" for the year 2017-2018 Applications recieved = 1837 Total fee collected = Rs. 2,20,541 Receipt Sl. No. Date Name of the Society District No. Copy Name Name Branch Change Change Challan Address Renewal Certified No./Date Duplicate 1 02410237 01-04-2017 NABAJYOTI RURAL DEVELOPMENT SOCIETY Barpeta 200 640/3-3-17 Barpeta 2 02410238 01-04-2017 MISSION TO THE HEARTS OF MILLION Barpeta 130 10894/28-3-17 Barpeta 3 02410239 01-04-2017 SEVEN STAR SOCIETY Barpeta 200 2935/9-3-17 Barpeta 02410240 Barpeta 4 01-04-2017 SIPNI SOCIO ECONOMIC AND CULTURAL DEVELOPMENT ORGANISATION 100 5856/15-2-17 Barpeta 5 02410241 01-04-2017 DESTINY WELFARE SOCIETY Barpeta 100 5857/15-2-17 Barpeta 08410259 Dhubri 6 01-04-2017 DHUBRI DISTRICT ENGINE BOAT (BAD BADHI) OWNER ASSOCIATION 75 14616/29-3-17 Dispur 7 15411288 03-04-2017 SOCIETY FOR CREATURE KAM(M) 52 40/3-4-17 Dispur 8 15411289 03-04-2017 MANAGEMENT COMMITTEE DAKHIN GUWAHATI JATIYA BIDYALAYA KAM(M) 125 15032/30-2-17 Dispur 9 24410084 03-04-2017 UNNATI SIVASAGAR 100 11384/15-3-17 Dispur 10 27410050 03-04-2017 AMGULI GAON MICRO WATERSHED COMMITTEE Udalguri 75 11836/16-2-17 Dispur 11 27410051 03-04-2017 MANPUR MICRO WATERSHED COMMITTEE Udalguri 75 11837/15-2-17 Dispur 12 27410052 03-04-2017 ULUBARI MICRO WATERSHED COMMITTEE Udalguri 75 11835/16-2-17 Dispur 13 15411291 04-04-2017 ST. CLARE CONVENT EDUCATIONAL SOCIETY KAM(M) 100 342/5-4-17 Dispur 14 16410228 04-04-2017 SERAPHINA SEVA SAMAJ KAM(R) 60 343/5-4-17 Dispur 15 16410234 -

Ethnic History and Identity of the Zo Tribes in North East India

Journal of North East India Studies Vol. 5(1), Jan.-Jun. 2015, pp. 39-50. Ethnic History and Identity of the Zo Tribes in North East India H. Thangtungnung North East India is a hotspot of identity crisis and ethnic divisions. The Chin, Kuki, Zomi and Mizo tribes who are collectively known as Zo people are no exception. They have close cultural, lingual and religious affinities and a com- mon ancestor called Zo. Historically, they have different theories of origin and migration based on their folklores, folktales and songs narrated down from one generation to another. The different origin theories like the Khul/Chhinlung or Cave origin theory, Chin Hills origin theory and Lost tribe (Manmasi) theory are among the most significant theories so far which speak, to some extent, some- thing about their history and origin. Of late, the Lost Tribe theory has gained momentum which claims that the Zo tribes are among the ten lost tribes of Israel, particularly from the tribe of Manasseh. Israeli Chief Rabbi Shlomo Amar had recognised them as descendents of Israel in 2005, which was also approved by the Israeli government. Many have consequently immigrated to the ‘Holy Land’. In this backdrop, this paper is attempts to critically analyse and assess the ethnic origin of the Zo people with special reference to the lost tribe theory. Based on cultural and oral traditions, and Biblical sources, it also attempts to support that the Zo people are the ten lost tribe of Israel by substantiating various arguments to validate this origin theory. Keywords: Zo, Khul origin theory, Chin Hills theory, Lost tribe, Manmasi Introduction The Zo people are indigenous tribes of Manipur and Mizoram in Northeast India, Bangladesh and Chin State of Myanmar. -

TERRORISM a VIF Analysis

TWELVE ESSAYS ON TERRORISM A VIF Analysis TWELVE ESSAYS ON TERRORISM A VIF Analysis Edited by Lt Gen Gautam Banerjee Foreword by Gen NC Vij, PVSM, UYSM, AVSM Director, Vivekananda International Foundation, New Delhi Vivekananda International Foundation New Delhi PENTAGON PRESS Twelve Essays on Terrorism Editor: Lt Gen Gautam Banerjee Vivekananda International Foundation, New Delhi ISBN 978-81-8274-942-9 First Published in 2017 Copyright © RESERVED All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the Publisher. Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in the book are the individual assertion of the Authors. The Publisher does not take any responsibility for the same in any manner whatsoever. The same shall solely be the responsibility of the Authors. Published by PENTAGON PRESS 206, Peacock Lane, Shahpur Jat, New Delhi-110049 Phones: 011-64706243, 26491568 Telefax: 011-26490600 email: [email protected] website: www.pentagonpress.in Printed at Avantika Printers Private Limited. CONTENTS Foreword vii Preamble ix List of Contributors xi 1. Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) and its South Asian Connection: An Indian Perspective 1 Alvite Singh Ningthoujam 2. International Terrorism Post 9/11: Emerging Trends and Global Response 18 Rohit Singh 3. Maoist Insurgency: Escalation and Dimensions of the State’s Armed Response 56 Lt Gen Gautam Banerjee 4. Terror Financing and the Global CTF Regime 86 Abhinav Pandya and C.D. Sahay 5. Taxation and Extortion: A Major Source of Militant Economy in North-East India 120 Brigadier Sushil Kumar Sharma 6. -

Militancy and Negotiations: a Study of Suspension of Operation in Manipur

Militancy and Negotiations: A Study of Suspension of Operation in Manipur Ch. Sekholal Kom* To resolve conflict and avoid the use of force, it is said, one must negotiate - Fred C. Iklé Abstract One of the most striking features of militancy in Northeast India in general and Manipur in particular is how infrequently the two sides (Government and the militants) attempt peaceful negotiation. Very often, the government refuses to grant the militants legitimacy as a bargaining partner. On the other, militants in the region are averse to go into negotiation with the government whom they confront. However, in spite of this phenomenon, confrontations do reach a point at a certain stage where both sides agree to negotiate rather than confront each other. Remarkably, the present tripartite truce popularly known as Suspension of Operation (SoO) between the Government of India and the state government of Manipur on one side and the Kuki militants on the other turns out to be a significant development. The paper discusses how this negotiation can be attributed as a technique of alternative dispute resolution in a multi-ethnic situation particularly in a conflict-ridden state like Manipur. Right since the dawn various militant ethnic groups. of independence of the Although Naga militancy was the country, Northeast first to make its headway in the India has been witnessing a region, movements by other series of challenges such as ethnicities followed it. Notably, the unceasing demands for autonomy militant activities of the Nagas, the and even outright secessions by Kukis, the Bodos, and the Assamese *Ch. Sekholal Korn is a Ph. -

Chapter Four Contemporary Conflicts and Challenges to Peace in South

Chapter Four Contemporary Conflicts and Challenges to Peace in South Asia Introduction South Asia has been one of the least peaceful regions in the world. Four full-scale interstate wars and a number of other low-intensity armed conflicts, ethnic conflicts, secessionist movements, and terrorism have mounted stiff challenges to peace in the region. Instability in the region is further perpetuated by the troubled relations between India and Pakistan, internal conflicts in Pakistan and Afghanistan, and militancy and movement for secession in Kashmir. India-Pakistan rivalry and Kashmir conflict has the potential to destabilise the entire South Asian landscape. Such a widespread threat to peace hardly emerges from the Sri Lanka Civil War, ethnic conflict in Bangladesh, secessionist movements in India‟s Northeast, left-wing extremism in India, and internal conflicts in Afghanistan and Pakistan. That is the reason why peaceful relations between India and Pakistan, and peace in Kashmir are crucial for regional peace and stability. This chapter briefly discusses the major internal and interstate conflicts in South Asia and makes an analysis of the potential sources of threats to peace, and how those threats can be mitigated through early preventive efforts. The focal point of the analysis is the status of all conflicts in the region in order to decipher the potential sources of threats to regional peace. For the purpose of brevity, the analysis does not intend going deeper into historical evolution of South Asian conflicts but dwells on a very concise introduction to present a brief idea of what possible threats could emerge in near future.