Quest for Nagalim: Mapping of Perceptions Outside Nagaland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Study on Human Rights Violation of Tangkhul Community in Ukhrul District, Manipur

A STUDY ON HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATION OF TANGKHUL COMMUNITY IN UKHRUL DISTRICT, MANIPUR. A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE TILAK MAHARASHTRA VIDYAPEETH, PUNE FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN SOCIAL WORK UNDER THE BOARD OF SOCIAL WORK STUDIES BY DEPEND KAZINGMEI PRN. 15514002238 UNDER THE GUIDANCE OF DR. G. R. RATHOD DIRECTOR, SOCIAL SCIENCE CENTRE, BVDU, PUNE SEPTEMBER 2019 DECLARATION I, DEPEND KAZINGMEI, declare that the Ph.D thesis entitled “A Study on Human Rights Violation of Tangkhul Community in Ukhrul District, Manipur.” is the original research work carried by me under the guidance of Dr. G.R. Rathod, Director of Social Science Centre, Bharati Vidyapeeth University, Pune, for the award of Ph.D degree in Social Work of the Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth, Pune. I hereby declare that the said research work has not submitted previously for the award of any Degree or Diploma in any other University or Examination body in India or abroad. Place: Pune Mr. Depend Kazingmei Date: Research Student i CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the thesis entitled, “A Study on Human Rights Violation of Tangkhul Community in Ukhrul District, Manipur”, which is being submitted herewith for the award of the Degree of Ph.D in Social Work of Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth, Pune is the result of original research work completed by Mr. Depend Kazingmei under my supervision and guidance. To the best of my knowledge and belief the work incorporated in this thesis has not formed the basis for the award of any Degree or similar title of this or any other University or examining body. -

Development of Education Among the Tangkhul in Ukhrul (Is an Abstract of the Presenter Thesis Entitle “Education of the Tribal

© 2021 JETIR February 2021, Volume 8, Issue 2 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) Development of Education among the Tangkhul in Ukhrul (is an abstract of the presenter thesis entitle “Education of the Tribals in Manipur- development, practice and problems with special reference to Ukhrul District) Dr. Khayi Philawon Assistant professor Pettigrew College Introduction:- Ukhrul is located at the east of Manipur state. It has an average elevation of 1662m (5452feet) above the sea level. It has wet summer and cold, dry winter. Ukhrul district is divided into two district recently as Ukhrul District and Kamjong District. But the present study will be limited till 1991. The Tangkhul Naga tribe inhabit the Ukhrul district. The tribals of Manipur is broadly categorise into the Nagas and the Kuki-Chin tribes. The 31 tribes, of Manipur falls into these two major tribes of Manipur Nagas Kukichin 1. Ailmol 1. Zou 2. Anal 2. Simte 3. Angami 3. Gangte 4. Chiru 4. Any Mizo 5. Chothe 5. Hmar 6. Koireng 6.Thadou – Ralte 7. Kairao 7. Paite 8. Maram/Thangal 8.Vaiphei – Salhte 9. Lamkang 10. Zeliang – Pumei – Rongmei – Rong – Kaccha Naga – Zemi – Liangmei 11. Kom 12. Tarao – Mayon 13. Mao – Paomei 14. Maring 15. Purum 16. Sema JETIR2102233 Journal of Emerging Technologies and Innovative Research (JETIR) www.jetir.org 1926 © 2021 JETIR February 2021, Volume 8, Issue 2 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) The Tangkhuls are one Naga tribes of Manipur. Though the majority of the people settle in Ukhrul district, they were scattered all over Manipur. The Tangkhuls were tall with large head and heavy stoiled feature, as a rule. -

Sebuah Kajian Pustaka

International Journal of Research in Social Sciences Vol. 8 Issue 7, July 2018, ISSN: 2249-2496 Impact Factor: 7.081 Journal Homepage: http://www.ijmra.us, Email: [email protected] Double-Blind Peer Reviewed Refereed Open Access International Journal - Included in the International Serial Directories Indexed & Listed at: Ulrich's Periodicals Directory ©, U.S.A., Open J-Gage as well as in Cabell‟s Directories of Publishing Opportunities, U.S.A Conflicts in Northeast India: Intra-state conflicts with reference to Assam Dharitry Borah Debotosh Chakraborty Abstract Conflict in Northeast India has a brand entity that entrenched country‟s name in the world affairs for decades. In this paper, an attempt was made to study the genesis of conflicts in Northeast India with special emphasis on the intra-state conflicts in Assam. Attempts Keywords: were also made to highlight reasons why Northeast India has Conflict; remained to be a highly conflict ridden area comparing to other parts Sovereignty; of India. The findings revealed that the state has continued to be a Separate homeland; hub for several intra-state conflicts – as some particular groups raised Indian State demand for a sovereign state, while some others are betrothed in demanding for a separate state or homeland. There exists a strong nexus between historical circumstances and their intertwined influence on the contemporary conflict situations in the State. For these deep-rooted influences, critical suggestions are incorporated in order to deal with the conflicts and to bring sustainable and long- lasting peace in the State. Ph.D. Candidate, Department of Political Science, Assam University, Silchar, Assam, India Assistant Professor, Department of Political Science, Assam University, Silchar, Assam, India 715 International Journal of Research in Social Sciences http://www.ijmra.us, Email: [email protected] ISSN: 2249-2496Impact Factor: 7.081 1. -

Survey of Conflicts & Resolution in India's Northeast

Survey of Conflicts & Resolution in India’s Northeast? Ajai Sahni? India’s Northeast is the location of the earliest and longest lasting insurgency in the country, in Nagaland, where separatist violence commenced in 1952, as well as of a multiplicity of more recent conflicts that have proliferated, especially since the late 1970s. Every State in the region is currently affected by insurgent and terrorist violence,1 and four of these – Assam, Manipur, Nagaland and Tripura – witness scales of conflict that can be categorised as low intensity wars, defined as conflicts in which fatalities are over 100 but less than 1000 per annum. While there ? This Survey is based on research carried out under the Institute’s project on “Planning for Development and Security in India’s Northeast”, supported by the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA). It draws on a variety of sources, including Institute for Conflict Management – South Asia Terrorism Portal data and analysis, and specific State Reports from Wasbir Hussain (Assam); Pradeep Phanjoubam (Manipur) and Sekhar Datta (Tripura). ? Dr. Ajai Sahni is Executive Director, Institute for Conflict Management (ICM) and Executive Editor, Faultlines: Writings on Conflict and Resolution. 1 Within the context of conflicts in the Northeast, it is not useful to narrowly define ‘insurgency’ or ‘terrorism’, as anti-state groups in the region mix in a wide range of patterns of violence that target both the state’s agencies as well as civilians. Such violence, moreover, meshes indistinguishably with a wide range of purely criminal actions, including drug-running and abduction on an organised scale. Both the terms – terrorism and insurgency – are, consequently, used in this paper, as neither is sufficient or accurate on its own. -

Review of Research

Review Of ReseaRch impact factOR : 5.7631(Uif) UGc appROved JOURnal nO. 48514 issn: 2249-894X vOlUme - 8 | issUe - 7 | apRil - 2019 __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ AN ANALYSIS OF THE AUTONOMY MOVEMENT OF HILL TRIBES OF ASSAM Ishani Senapoti Research Scholar, Department of Political Science Gauhati University, Guwahati, Assam, India. ABSTRACT : Movements for Autonomy have marked the political discourse in Northeast India for the last decades. The aim and purpose of the autonomy movement is not only to bring about change in the existing system but also to augment legitimate expressions of aspirations by the people having a distinct culture, tradition and common pattern of living. In the post colonial period, Assam which is a land of diverse ethnic communities has witnessed a serious of autonomy movements based on the political demands for statehood. The autonomy movement of the Hill Tribals in North East India in general and North Cachar Hills District and Karbi Anglong District of Assam in particular is a continuous effort and struggle of the Hill Tribal to protect and preserve their distinct identity, culture and tradition and to bring about a change in the existing socio-political arrangement. Although the Sixth Schedule of the Indian Constitution has provided for Autonomous Councils in these two districts but much improvement could not be achieved due to limited power of the Autonomous District Council and the State government’s apathy. Their demand for an autonomous state is rooted in the long history of similar movements in the north east and has been demanding a separate state for the Dimasas and the Karbis in the name of ‘Dimaraji’ for Dimasas and ‘Hemprek’ for Karbis. -

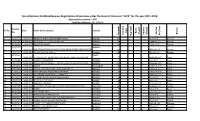

Fee Collections for Miscellaneous Registration of Societies Under The

Fee collections for Miscellaneous Registration of Societies under the Head of Accounts "1475" for the year 2017-2018 Applications recieved = 1837 Total fee collected = Rs. 2,20,541 Receipt Sl. No. Date Name of the Society District No. Copy Name Name Branch Change Change Challan Address Renewal Certified No./Date Duplicate 1 02410237 01-04-2017 NABAJYOTI RURAL DEVELOPMENT SOCIETY Barpeta 200 640/3-3-17 Barpeta 2 02410238 01-04-2017 MISSION TO THE HEARTS OF MILLION Barpeta 130 10894/28-3-17 Barpeta 3 02410239 01-04-2017 SEVEN STAR SOCIETY Barpeta 200 2935/9-3-17 Barpeta 02410240 Barpeta 4 01-04-2017 SIPNI SOCIO ECONOMIC AND CULTURAL DEVELOPMENT ORGANISATION 100 5856/15-2-17 Barpeta 5 02410241 01-04-2017 DESTINY WELFARE SOCIETY Barpeta 100 5857/15-2-17 Barpeta 08410259 Dhubri 6 01-04-2017 DHUBRI DISTRICT ENGINE BOAT (BAD BADHI) OWNER ASSOCIATION 75 14616/29-3-17 Dispur 7 15411288 03-04-2017 SOCIETY FOR CREATURE KAM(M) 52 40/3-4-17 Dispur 8 15411289 03-04-2017 MANAGEMENT COMMITTEE DAKHIN GUWAHATI JATIYA BIDYALAYA KAM(M) 125 15032/30-2-17 Dispur 9 24410084 03-04-2017 UNNATI SIVASAGAR 100 11384/15-3-17 Dispur 10 27410050 03-04-2017 AMGULI GAON MICRO WATERSHED COMMITTEE Udalguri 75 11836/16-2-17 Dispur 11 27410051 03-04-2017 MANPUR MICRO WATERSHED COMMITTEE Udalguri 75 11837/15-2-17 Dispur 12 27410052 03-04-2017 ULUBARI MICRO WATERSHED COMMITTEE Udalguri 75 11835/16-2-17 Dispur 13 15411291 04-04-2017 ST. CLARE CONVENT EDUCATIONAL SOCIETY KAM(M) 100 342/5-4-17 Dispur 14 16410228 04-04-2017 SERAPHINA SEVA SAMAJ KAM(R) 60 343/5-4-17 Dispur 15 16410234 -

Vol.VI, No.II, July-December, 2018

Volume: VI, Number: II July - December, 2018 ISSN: 2319-8192 Intellection $%LDQQXDO,QWHUGLVFLSOLQDU\5HVHDUFK-RXUQDO Editorial Board Chief Editor: Prof. Nikunja Bihari Biswas, Former Dean, Ashutosh Mukharjee School of Educational Sciences, Assam University, Silchar Editor Managing Editor Dr.Baharul Islam Laskar , Dr. Abul Hassan Chaudhury Principal , Assistant Registrar, M.C.D College, Sonai, Cachar Assam University, Silchar Associate Editors Dr. S.M.Alfarid Hussain, Dr. Anindya Syam Choudhury, Assistant Professor, Department of Mass Associate Professor, Department of English, Communication, Assam University, Silchar Assam University, Silchar Assistant Managing Editors Dr. Monjur Ahmed Laskar, Dr. Nijoy Kr Paul Research Associate, Professional Assistant, Central Library, Bioinformatics Centre, Assam University, Assam University, Silchar EDITORIAL BOARD MEMBERS Dr. Humayun Bokth , Prof J.U Ahmed , Associate Professor, Department of Sociology, Department of Management, NEHU, Assam University Tura Campus Dr. Merina Islam, (founder Editor), Dr. Pius V.T, Associate Professor, Department of Assistant Professor, Department of Philosophy, Philosophy , Cachar College, Silchar Assam University, Silchar Dr. Kh Narendra Singh, Prof Sk Jasim Uddin, Head, Department of Anthropology, Department of Chemistry, Assam University, Assam University, Diphu Campus Silchar Dr.Himadri Sekhar Das , Dr. Debotosh Chakraborty Assistant Professor, Department of Physics, Assistant Professor, Department of Political Assam university, Silchar Science, Assam University, Silchar Dr. Moynul Hoque, Dr. Md. Aynul Hoque, Assistant professor, Department of History, Former Assistant Professor, Gurucharan College, Silchar NERIE, Shillong Dr. Taj Uddin Khan Dr. Subrata Sinha, Assistant Professor, Deptt.of Botany, System Analyst, Computer Centre, S.S.College, Hailakandi Assam University, Silchar Dr. Ayesha Afsana Dr. Ganesh Nandi Former Guest Faculty, Deptt. of Law, Asstt. Professor, Deptt. -

Tariff Order

2 TARIFF ORDER PROVISIONA L TRUE -UP F OR FY 2019-20 REVIEW FOR FY 2020-21 AND DETERMINATION OF AGGREGATE REVENUE REQUIREMENT & TRANSMISSION TARIFF FOR FY 2021-22 FOR MANIPUR STATE POWER COMPANY LIMITED Petition (ARR & Tariff) No. 2 of 2021 JOINT ELECTRICITY REGULATORY COMMISSION FOR MANIPUR AND MIZORAM MSPCL Tariff Order for FY 2021-22 CONTENTS ORDER ................................................................................................................................................. 1 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 7 1.1 JERC for Manipur and Mizoram (JERC, M&M) ........................................................................... 7 1.2 Manipur State Power Company Ltd ........................................................................................... 9 2. Summary of the ARR & Tariff Petition for FY 2021-22 ............................................................. 11 2.1 Aggregate Revenue Requirement (ARR) .................................................................................. 11 2.2 Target availability ..................................................................................................................... 11 2.3 Transmission Loss ..................................................................................................................... 11 2.4 Transmission ARR and transmission tariff proposal for FY 2021-22 ........................................ 12 2.5 Rebate ..................................................................................................................................... -

TOURISM INNOVATIONS an International Journal of Indian Tourism and Hospitality Congress (ITHC)

Vol. 9, No. 1, February, 2019 Bi-Annual ISSN No. 2278-8379 TOURISM INNOVATIONS An International Journal of Indian Tourism and Hospitality Congress (ITHC) Chief Editors Prof. S P Bansal Vice Chancellor Indira Gandhi University Meerpur Rewari, Haryana Prof. Sandeep Kulshrestha Director Indian Institute of Tourism and Travel Management, (IITTM) Indian Tourism and Hospitality Congress www.tourismcongress.wordpress.com Tourism Innovations: An International Journal of Indian Tourism and Hospitality Congress (ITHC) Copyright : Indian Tourism and Hospitality Congress (ITHC) Reproduction in whole or in part, in any form without written permission is prohibited. ISSN : 2278-8379 VOLUME : 9 NUMBER : 1 Publication Schedule: Twice a year : February-August Disclaimer: The views expressed in the articles are those of the contributors and not necessarily to the editorial board and publisher. Authors are themselves responsible for any kind of Plagiarism found in their articles and any related issue. Claims and court cases only allowed within the jurisdiction of HP, India Published by: Bharti Publications in Association with Indian Tourism and Hospitality Congress (ITHC) All Correspondence Should be Address to : Managing Editor Tourism Innovations Bharti Publications 4819/24, 3rd Floor, Mathur Lane Ansari Road, Daryaganj, New Delhi-110002 Ph: 011-2324-7537 Email: [email protected], [email protected] Website: www.indiantourismcongress.org, www.tourismcongress.wordpress.com Editors Note “Research is to see what everybody else has seen and to think what nobody else has thought.” — Albert Szent-Gyorgyi We are delighted to announce the new issue of Tourism Innovations-the Journal of Indian Tourism and Hospitality Congress. It is truly a delightful moment to reflect the evolving issues of tourism with contemporary date, high excellence and original research papers together withsignificant and insightful reviews. -

Parents Training Programme Cum Meet Conducted Organisations Appeal Government to Protect Drug Users from Abuse PAM Organises

IMPHAL, SUNDAY, MARCH 14, 2021 Photo exhibition inaugurated Organisations appeal Government Parents Training Programme to protect drug users from abuse cum Meet conducted By Our Staff Reporter abuse by publishing it in users violates human rights IMPHAL, Mar 13 the resource persons of to- Disabilities certificate in or- the State Gazette on De- and is against the law, he day's programme. der to take benefits of such IMPHAL, Mar 13: cember 18, 2020, the same claimed that there are re- Relief Centre for the Welfare Speaking on the occasion, useful schemes. Community Network for rules have not been strictly ports that some of the of Differently Abled Persons Nimol Ningombam elabo- He further called for col- Empowerment (CoNE), followed by the rehabilita- rehabilitation centres are Manipur under the aegis of rated about the causes of lective efforts from all to Users’ Society for Effective tion centres. not returning/releasing the Ministry of Social Justice and different forms of disabili- help the disabled persons Response (USER) and Alleging that staff of inmates when their parents Empowerment, Government ties. lead a normal life. Kangleipak Drug Re-integration Rehabilita- and guardians approached of India organised a Parents He stated that the pro- Chuongsin Koireng Awareness and Prevention tion Centre at Ayangpalli to move their wards to Training Programme cum gramme is being organised stated that one should not (KADAP) have urged the Mutum Leikai had tried to other rehabilitation centres Parents Meet 2021 today at to sensitize the people on leave the disabled persons Government and the forcibly institutionalise a which cost less. -

February 12 Page 1

Evening daily Imphal Times Regd.No. MANENG /2013/51092 Volume 5, Issue 32, Sunday, February 12, 2017 www.imphaltimes.com Maliyapham Palcha Kumshing 3414 2/- Ibobi silence on status of Congress party BJP and Congress likely to have CM Okram Ibobi, Okram Joy among others hoisted flags straight fight in Singjamei AC IT News IT News Candidate Yumnam constituency”, said Robert. Imphal, Feb 12: The battle is Imphal, Feb 12: A day after Khemchand to have a straight He however did not say on now. Congress party BJP ticket seeker Oinam fight in the constituency. anything on whom he will strong man Chief Minister Romen of Singjamai Assembly Ngangbam Robert was listed support in this election. Okram Ibobi today hoisted the Constituency had announced among the list of NPP Follwing his announcement it party flag at his residence at his decision to support the candidates who had been is likely that BJP candidate Y Thoubal Athokpam. Veteran BJP candidate after he was approved for contesting the Khemchand and Congress politician Okram Joy, who is denied party ticket, another election. All of a sudden he Candidate I Hemochandra contesting the upcoming BJP ticket seeker, who had announced that he will not may have a straight fight in the election at Langthabal lately joined NPP, Nangbam contest the upcoming constituency. Assembly constituency as Robert today said that he too assembly poll. Last general election too, both BJP candidate also hoisted the will not contest the election “I took the decision not to the candidates have straight party at his residence at not give any comment to as BJP candidate for the first Both the Okrams are known this time clearing the way for contest this time after fight and Congress candidate Kakwa. -

Traditional Methods of Conflict Resolution in Three Tribal Societies of North East India

NESRC Peace Studies Series–4 Traditional Methods of Conflict Resolution in Three Tribal Societies of North East India Editor Alphonsus D’Souza North Eastern Social Research Centre Guwahati 2011 Contents Acknowledgements Introduction Alphonsus D’Souza / 1 Traditional Methods of Conflict Management among the Dimasa Padmini Langthasa / 5 The Karbi Community and Conflicts Sunil Terang Dili / 32 Traditional Methods of Conflict Resolution Adopted by the Lotha Naga Tribe Blank Yanlumo Ezung / 64 2 TRADITIONAL METHODS OF CONFLICT RESOLUTION INTRODUCTION 3 system rather than an adversarial and punitive system. inter-tribal conflicts were resolved through In a criminal case, the goal is to heal and restore the negotiations and compromises so that peaceful victim’s well-being, and to help the offender to save relations could be restored. face and to regain dignity. In a civil case, the parties In the case of internal conflicts, all the three involved are helped to solve the dispute in a way communities adopted very similar, if not identical, that there are no losers, but all are winners. The mechanisms, methods and procedures. The elders ultimate aim is to restore personal and communal played a leading role. The parties involved were given harmony. ample opportunities to express their grievances and The three essays presented here deal with the to present their case. Witnesses were examined and traditional methods of conflict resolution practised cross examined. In extreme cases when evidence was in three tribal communities in the Northeast. These not very clear, supernatural powers were invoked communities have many features in common. All the through oaths. The final verdict was given by the elders three communities have their traditional habitat, in such a way that the guilty were punished, injustices distinctive social organisation and culture.