Directing Tartuffe Or Why Should People See This Show Today?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dossier De Presse

Atypik Films Présente Patrick Ridremont François Berléand Virginie Efira DEAD MAN TALKING Un film belge de PATRICK RIDREMONT (Durée : 1h41) Distribution Relations Presse Atypik Films Laurence Falleur Communication 31 rue des Ombraies 57 rue du Faubourg Montmartre 92000 Nanterre 75009 Paris Eric Boquého Laurence Falleur Assisté de Sandrine Becquart Assisté de Vincent Bayol Et Jacques Domergue Tel : 01.83.92.80.51 Tel : 01.77.68.32.16. Port. : 06.48.89.41.29 Port. : 06.62.49.19.87. [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Matériel de presse téléchargeable sur www.atypikfilms.com SYNOPSIS William Lamers , 40 ans, anonyme criminel condamné au Poison pour meurtre, se prépare à être exécuté. La procédure se passe dans l’indifférence générale et, ni la famille du condamné, ni celle de ses victimes n’a fait le déplacement pour assister à l’exécution. Seul le journaliste d’un minable tabloïd local est venu assister au «spectacle». Pourtant ce qui ne devait être qu’une formalité va rapidement devenir un véritable cauchemar pour Karl Raven, le directeur de la prison. Alors qu’on lui demande s’il a quelque chose à dire avant de mourir, William se met à raconter sa vie, et se lance dans un récit incroyable et bouleversant. Raven s’impatiente et appelle le Gouverneur Brodeck pour obtenir l'autorisation d'exécuter William. Mais comme la loi ne précise rien sur la longueur des dernières paroles et que le Gouverneur Stieg Brodeck, au plus bas dans les sondages, ne peut prendre aucun risque à un mois des élections, on décide de laisser William raconter son histoire jusqu’au bout. -

Course Catalogue 2016 /2017

Course Catalogue 2016 /2017 1 Contents Art, Architecture, Music & Cinema page 3 Arabic 19 Business & Economics 19 Chinese 32 Communication, Culture, Media Studies 33 (including Journalism) Computer Science 53 Education 56 English 57 French 71 Geography 79 German 85 History 89 Italian 101 Latin 102 Law 103 Mathematics & Finance 104 Political Science 107 Psychology 120 Russian 126 Sociology & Anthropology 126 Spanish 128 Tourism 138 2 the diversity of its main players. It will thus establish Art, Architecture, the historical context of this production and to identify the protagonists, before defining the movements that Music & Cinema appear in their pulse. If the development of the course is structured around a chronological continuity, their links and how these trends overlap in reality into each IMPORTANT: ALL OUR ART COURSES ARE other will be raised and studied. TAUGHT IN FRENCH UNLESS OTHERWISE INDICATED COURSE CONTENT : Course Outline: AS1/1b : HISTORY OF CLASSIC CINEMA introduction Fall Semester • Impressionism • Project Genesis Lectures: 2 hours ECTS credits: 3 • "Impressionist" • The Post-Impressionism OBJECTIVE: • The néoimpressionnism To discover the great movements in the history of • The synthetism American and European cinema from 1895 to 1942. • The symbolism • Gauguin and the Nabis PontAven COURSE PROGRAM: • Modern and avantgarde The three cinematic eras: • Fauvism and Expressionism Original: • Cubism - The Lumière brothers : realistic art • Futurism - Mélies : the beginnings of illusion • Abstraction Avant-garde : - Expressionism -

Stéphane Braunschweig Théâtre De L'odéon- 6E

de Molière 17 septembre 25 octobre 2008 mise en scène & scénographie Stéphane Braunschweig Théâtre de l'Odéon- 6e costumes Thibault Vancraenenbroeck lumière Marion Hewlett son Xavier Jacquot collaboration artistique Anne-Françoise Benhamou collaboration à la scénographie Alexandre de Darden production Théâtre national de Strasbourg créé le 29 avril 2008 au Théâtre national de Strasbourg avec Monsieur Loyal : Jean-Pierre Bagot Cléante : Christophe Brault Tartuffe : Clément Bresson Valère : Thomas Condemine Orgon : Claude Duparfait Mariane : Julie Lesgages Elmire : Pauline Lorillard Dorine : Annie Mercier Damis : Sébastien Pouderoux Madame Pernelle : Claire Wauthion et avec la participation de l’exempt : François Loriquet Rencontre Spectacle du mardi au samedi à 20h, le dimanche à 15h, relâche le lundi Au bord de plateau jeudi 2 octobre Prix des places : 30€ - 22€ - 12€ - 7,50€ (séries 1, 2, 3, 4) à l’issue de la représentation, Tarif groupes scolaires : 11€ et 6€ (séries 2 et 3) en présence de l’équipe artistique. Entrée libre. Odéon–Théâtre de l’Europe Théâtre de l’Odéon Renseignements 01 44 85 40 90 e Place de l’Odéon Paris 6 / Métro Odéon - RER B Luxembourg L’équipe des relations avec le public : Scolaires et universitaires, associations d’étudiants Réservation et Actions pédagogiques Christophe Teillout 01 44 85 40 39 - [email protected] Emilie Dauriac 01 44 85 40 33 - [email protected] Dossier également disponible sur www.theatre-odeon.fr Certaines parties de ce dossier sont tirées du dossier pédagogique et du programme réalisés par l’équipe du Théâtre national de Strasbourg. Collaboration d’Arthur Le Stanc Tartuffe / 17 septembre › 25 octobre 2008 1 Oui, je deviens tout autre avec son entretien, Il m'enseigne à n'avoir affection pour rien ; De toutes amitiés il détache mon âme ; Et je verrais mourir frère, enfants, mère, et femme, Que je m'en soucierais autant que de cela. -

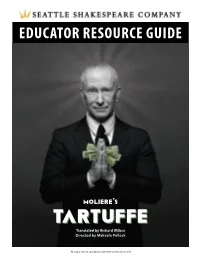

Translated by Richard Wilbur Directed by Makaela Pollock

Translated by Richard Wilbur Directed by Makaela Pollock All original material copyright © Seattle Shakespeare Company 2015 WELCOME Dear Educators, Tartuffe is a wonderful play, and can be great for students. Its major themes of hypocrisy and gullibility provide excellent prompts for good in-class discussions. Who are the “Tartuffes” in our 21st century world? What can you do to avoid being fooled the way Orgon was? Tartuffe also has some challenges that are best to discuss with students ahead of time. Its portrayal of religion as the source of Tartuffe’s hypocrisy angered priests and the deeply religious when it was first written, which led to the play being banned for years. For his part, Molière always said that the purpose of Tartuffe was not to lampoon religion, but to show how hypocrisy comes in many forms, and people should beware of religious hypocrisy among others. There is also a challenging scene between Tartuffe and Elmire at the climax of the play (and the end of Orgon’s acceptance of Tartuffe). When Tartuffe attempts to seduce Elmire, it is up to the director as to how far he gets in his amorous attempts, and in our production he gets pretty far! This can also provide an excellent opportunity to talk with students about staunch “family values” politicians who are revealed to have had affairs, the safety of women in today’s society, and even sexual assault, depending on the age of the students. Molière’s satire still rings true today, and shows how some societal problems have not been solved, but have simply evolved into today’s context. -

Course Booklet

On joining King’s you will be part of the most amazing peer group in the country. Welcome You and your fellow students will support, encourage and challenge each other through two years of outstanding teaching, learning, leadership and From the Associate Principal If you are a current student at King’s you will already know character development. and Director of Sixth Form that the staff here will go the extra mile for you, but whilst the fundamental ingredients which make us such a successful Dr Andrew Reay You will be able to achieve outstanding Academy remain, Sixth Form life is very different. You will be given greater autonomy and responsibilities, both for your own qualifications and go on to the best We are delighted that you are considering King’s Leadership Academy Sixth Form. This guide will not only development and for the well-being of others. For example, universities not just in this country but give you the information you need about the courses smart business dress is the order of the day and there is a across the world. that are best suited to your interests and aspirations, but Sixth Form Study Centre, IT suite and informal study area to also a deep insight into Sixth Form life. Most importantly, mark the distinction between life in the Sixth Form and the it will give you the confidence to know that by joining rest of the Academy. You will also be taught in even smaller King’s you are making the right move towards a very groups, have more self-directed study time, so that you are bright future. -

Dossier Pedagogique

banquet d’avril Directrice artistique : Monique Hervouët 06 11 11 21 88 [email protected] www.banquetd’avril.fr DOSSIER PEDAGOGIQUE LE TARTUFFE de Molière Mise en scène Monique Hervouët Création Octobre 2011 SOMMAIRE LE TARTUFFE de MOLIÈRE Mise en scène : Monique HERVOUET Compagnie banquet d’avril Coproduction : Le Grand R / Scène Nationale de la Roche-sur-Yon Avec Loïc AUFFRET Loyal /L’exempt/ Laurent • Mise en scène par Monique Hervouët Ghyslain DEL PINO Tartuffe Solenn JARNIOU Dorine Marion MALENFANT Mariane - Note d'intention : Monique Hervouët............................................................p 4 Glenn MARAUSSE Damis - Hypocrites......................................................................................................p 6 Jean-Pierre NIOBE Cléante - 3 Versions, 2 interdictions...............................................................................p 7 Hélori PHILIPPOT Valère - Résumé...........................................................................................................p 8 Hélène RAIMBAULT Mme Pernelle - L'auteur..........................................................................................................p 9 Gwenaël RAVAUX Elmire - Préface-avertissement de Molière à ses censeurs...............................................p 10 Didier ROYANT Orgon Scénographie Emilie LEMOINE Lumière Yohann OLIVIER • D'une mise en scène à l'autre (1907-2008) Chargée de production - communication Elise MAINGUY Administration Danièle OREFICE - Tartuffe à l'épreuve du temps..........................................................................p -

The Comic in the Theatre of Moliere and of Ionesco: a Comparative Study

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1965 The omicC in the Theatre of Moliere and of Ionesco: a Comparative Study. Sidney Louis Pellissier Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Pellissier, Sidney Louis, "The omicC in the Theatre of Moliere and of Ionesco: a Comparative Study." (1965). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 1088. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/1088 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received 66-744 PELLISSIER, Sidney Louis, 1938- s THE COMIC IN THE THEATRE OF MO LI ERE AND OF IONESCO: A COMPARATIVE STUDY. Louisiana State University, Ph.D., 1965 Language and Literature, modern University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan THE COMIC IN THE THEATRE OF MOLIHRE AND OF IONESCO A COMPARATIVE STUDY A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Foreign Languages btf' Sidney L . ,') Pellissier K.A., Louisiana State University, 19&3 August, 19^5 DEDICATION The present study is respectfully dedicated the memory of Dr. Calvin Evans. ii ACKNO'.-'LEDGEKiNT The writer wishes to thank his major professor, Dr. -

THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY PAUL SCOTT, University of Kansas

THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY PAUL SCOTT, University of Kansas 1. GENERAL Orientalism and discussions of identity and alterity form part of an identifiable trend in our field during the coverage of the two calendar years. Another strong current is the concept of libertinage and its literary and social influence. In terms of the first direction, Nicholas Dew, Orientalism in Louis XlV's France, OUP, 2009, xv+301 pp., publishes an overview of what he terms 'baroque Orientalism' and explores the topos through chapters devoted to the production of texts by d'Herbelot, Bernier, and Thevenot which would have an important reception and influence during the 18th century. The network of the Republic of Letters was crucial in gaining access to and studying oriental works and, while this was a marginal presence during the period, D. reveals how the curiosity of vth-c. scholars would lay the foundations of work that would be drawn on by the philosophes. Duprat, Orient, is an apt complement to Dew's volume, and A. Duprat, 'Le fil et la trame. Motifs orientaux dans les litteratures d'Europe' (9-17) maintains that the depiction of the Orient in European lit. was a common attempt to express certain desires but, at the same time, to contain a general angst as a result of incorporating scientific progress and territorial expansion. Brian Brazeau, Writing a New France, 1604-1632: Empire and Early Modern French Identity, Farnham, Ashgate, 2009, x +132 pp., selects the period following the end of the Wars of Religion because this early period of colonization gave rise to some of the most enthusiastic accounts as well as the fact that they established the pioneering debate for future narratives. -

Wider Reading and Discovery Lists for A-Level Helping You Fulfil Your Academic Potential

Wider Reading and Discovery Lists for A-Level Helping you fulfil your academic potential These lists will give you a broader understanding of your chosen subjects, compliment your core reading and enable your academic success. Whatever you study, you should be developing your reading, comprehension and critical thinking skills. However in depth subject knowledge can’t only be found in books, journals or periodicals. Discover more by visiting museums, galleries, theatres and academic institutions, stimulating your imagination and enhancing your core studies. 1 Contents Art – page 3 Biology – pages 3 and 4 Business Studies – page 4 Chemistry – pages 4 and 5 Computer Science – page 5 Design and Technology – page 5 Drama – pages 6 and 7 Economics – pages 7, 8 and 9 English Literature – pages 10 and 11 French – page 11 Geography – page 12 History – page 13 Law – page 14 Maths and Further maths – page 14 Media Studies – pages 14 and 15 Philosophy and Ethics – page 15 Physical Education – page 16 Physics –page 16 Psychology – page 17 Spanish – pages 17 and 18 Sociology – page 18 Other places for curious minds – page 19 2 Art Texts to read Story of Art by Ernst Gombrich History of Beauty by Umberto Eco Shock of the New by Robert Hughes Steal Like an Artist by Austin Kleon The Art Book by Phaidon Press Ltd. The Art Forger by Barbara A. Shapiro Ways of Seeing by John Berger Broad Strokes: 15 Women Who Made Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain Art and Made History (in That Order) by Betty Edwards by Bridget Quinn Seven Days in The Art -

Opening Moves, Dialectical Opposites, and Mme Pernelle by Allen G

Opening Moves, Dialectical Opposites, and Mme Pernelle by Allen G. Wood Tartuffe begins with an ending. Mme Pernelle departs from the Orgon household, commanding her servant: “Allons, Flipote, allons, que d’eux je me délivre.” (1). She does not leave, how- ever, without having the last word, or series of last words, as she showers criticism on every member of her extended family, the “eux” (them) from whom she disdainfully distinguishes herself. Dorine is “impertinente,” Damis a “sot,” Mariane is too “dis- crète,” (meaning sneaky). Elmire “dépensière,” while, finally, Cléante is sententious. Her attitude is “têtue et incivile” ( Ledoux, préface), but Mme Pernelle is both correct in her assessment, if wrong in her conclu- sions. Guicharnaud points out that each portrait is an : Erreur de jugement seulement, puisque le contenu de faits de ses portraits est exact. Cette erreur la conduit à des accusations graves. ...La suite de la pièce mettra chaque personnage dans une situation telle qu’il démentira précisément le jugement particulier que Mme Pernelle a porté sur lui au début du premier acte. (25) As the initial scene, it performs the important task of introduc- ing the main characters and the principal subject matter to the audience. As we know, this is especially crucial in a comedy, where neither characters nor plot elements are known by the spec- tators. But the way in which this is achieved in Tartuffe is atypical, even extravagant. The conventional opening scene of the time, and also found in Molière’s other plays, has a couple of characters discussing their situation and that of other characters. -

Graduate School of Arts and Sciences 2001–2002

Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Programs and Policies 2001–2002 bulletin of yale university Series 97 Number 10 August 20, 2001 Bulletin of Yale University Postmaster: Send address changes to Bulletin of Yale University, PO Box 208227, New Haven ct 06520-8227 PO Box 208230, New Haven ct 06520-8230 Periodicals postage paid at New Haven, Connecticut Issued sixteen times a year: one time a year in May, October, and November; two times a year in June and September; three times a year in July; six times a year in August Managing Editor: Linda Koch Lorimer Editor: David J. Baker Editorial and Publishing Office: 175 Whitney Avenue, New Haven, Connecticut Publication number (usps 078-500) Printed in Canada The closing date for material in this bulletin was June 10, 2001. The University reserves the right to withdraw or modify the courses of instruction or to change the instructors at any time. ©2001 by Yale University. All rights reserved. The material in this bulletin may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, in any form, whether in print or electronic media, without written permission from Yale University. Graduate School Offices Admissions 432.2773; [email protected] Alumni Relations 432.1942; [email protected] Dean 432.2733; susan.hockfi[email protected] Finance and Administration 432.2739; [email protected] Financial Aid 432.2739; [email protected] General Information Office 432.2770; [email protected] Graduate Career Services 432.2583; [email protected] McDougal Graduate Student Center 432.2583; [email protected] Registrar of Arts and Sciences 432.2330 Teaching Fellow Preparation and Development 432.2583; [email protected] Teaching Fellow Program 432.2757; [email protected] Working at Teaching Program 432.1198; [email protected] Internet: www.yale.edu/gradschool Copies of this publication may be obtained from Graduate School Student Services and Reception Office, Yale University, PO Box 208236, New Haven ct 06520-8236. -

At First Sight, the Character of Elmire in Molière's Tartuffe Appears to Have

Julia Prest ELMIRE AND THE EROTICS OE THE MENAGE A TROIS IN MOLIÈRE'S TARTUFFE t first sight, the character of Elmire in Molière's Tartuffe appears to have Amuch to commend her, and modern critics and theatergoers generally warm to her: she is attractive, stylish, independent, smart, resourceful, in many ways a modern woman.' Even older, more patriarchally inclined critics have generally been slow to condemn her,^ yet I would like to argue that rather than being a female exemplar who helps resolve the Tartuffe situation as is often stated, her function within the play is in many ways a disruptive one; she is a catalyst to the disintegration of the Orgon household and in practice contributes little toward the resolution of a plot that teeters on the brink of a tragic outcome. Here, I would like to restore some of the shock value to the character of Elmire, a shock value that has become lost over the centuries, overshadowed in particular by the even greater shock value of the provoca- tive religious dimension to the play. Yet it is surely no coincidence that the anonymous author of the Lettre sur la comédie de L'Imposteur (1667) defends the play against the twin accusations of attacking true religion and of pro- moting adultery. But the second of these continues to be overlooked in favor of the first. I shall insist on the extraordinary daring of Elmire's plan to trap Tartuffe in the famous "table scene" of which I shall propose a new reading. In particular, I would like to investigate the complex erotic overtones in the Elmire-Orgon-Tartuffe triangle,'' and to suggest that Elmire would be very 1.