The King's Men: Molière and Lully's Comédies-Ballets

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’S Opera and Concert Arias Joshua M

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 10-3-2014 The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias Joshua M. May University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation May, Joshua M., "The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias" (2014). Doctoral Dissertations. 580. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/580 ABSTRACT The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias Joshua Michael May University of Connecticut, 2014 W. A. Mozart’s opera and concert arias for tenor are among the first music written specifically for this voice type as it is understood today, and they form an essential pillar of the pedagogy and repertoire for the modern tenor voice. Yet while the opera arias have received a great deal of attention from scholars of the vocal literature, the concert arias have been comparatively overlooked; they are neglected also in relation to their counterparts for soprano, about which a great deal has been written. There has been some pedagogical discussion of the tenor concert arias in relation to the correction of vocal faults, but otherwise they have received little scrutiny. This is surprising, not least because in most cases Mozart’s concert arias were composed for singers with whom he also worked in the opera house, and Mozart always paid close attention to the particular capabilities of the musicians for whom he wrote: these arias offer us unusually intimate insights into how a first-rank composer explored and shaped the potential of the newly-emerging voice type of the modern tenor voice. -

Monsieur De Pourceaugnac, Comédie-Ballet De Molière Et Lully

Monsieur de Pourceaugnac, comédie-ballet de Molière et Lully Dossier pédagogique Une production du Théâtre de l’Eventail en collaboration avec l’ensemble La Rêveuse Mise en scène : Raphaël de Angelis Direction musicale : Florence Bolton et Benjamin Perrot Chorégraphie : Namkyung Kim Théâtre de l’Eventail 108 rue de Bourgogne, 45000 Orléans Tél. : 09 81 16 781 19 [email protected] http://theatredeleventail.com/ Sommaire Introduction ......................................................................................................................................... 2 La farce dans l’œuvre de Molière ................................................................................................ 3 Molière : éléments biographiques ............................................................................................. 3 Le comique de farce .................................................................................................................... 4 Les ressorts du comique dans Monsieur de Pourceaugnac .............................................. 5 Musique baroque et comédie-ballet ........................................................................................... 7 Qui est Jean-Baptiste Lully ? ........................................................................................................ 7 La musique dans Monsieur de Pourceaugnac ..................................................................... 8 La commedia dell’arte ................................................................................................................. -

103 the Music Library of the Warsaw Theatre in The

A. ŻÓRAWSKA-WITKOWSKA, MUSIC LIBRARY OF THE WARSAW..., ARMUD6 47/1-2 (2016) 103-116 103 THE MUSIC LIBRARY OF THE WARSAW THEATRE IN THE YEARS 1788 AND 1797: AN EXPRESSION OF THE MIGRATION OF EUROPEAN REPERTOIRE ALINA ŻÓRAWSKA-WITKOWSKA UDK / UDC: 78.089.62”17”WARSAW University of Warsaw, Institute of Musicology, Izvorni znanstveni rad / Research Paper ul. Krakowskie Przedmieście 32, Primljeno / Received: 31. 8. 2016. 00-325 WARSAW, Poland Prihvaćeno / Accepted: 29. 9. 2016. Abstract In the Polish–Lithuanian Common- number of works is impressive: it included 245 wealth’s fi rst public theatre, operating in War- staged Italian, French, German, and Polish saw during the reign of Stanislaus Augustus operas and a further 61 operas listed in the cata- Poniatowski, numerous stage works were logues, as well as 106 documented ballets and perform ed in the years 1765-1767 and 1774-1794: another 47 catalogued ones. Amongst operas, Italian, French, German, and Polish operas as Italian ones were most popular with 102 docu- well ballets, while public concerts, organised at mented and 20 archived titles (totalling 122 the Warsaw theatre from the mid-1770s, featured works), followed by Polish (including transla- dozens of instrumental works including sym- tions of foreign works) with 58 and 1 titles phonies, overtures, concertos, variations as well respectively; French with 44 and 34 (totalling 78 as vocal-instrumental works - oratorios, opera compositions), and German operas with 41 and arias and ensembles, cantatas, and so forth. The 6 works, respectively. author analyses the manuscript catalogues of those scores (sheet music did not survive) held Keywords: music library, Warsaw, 18th at the Archiwum Główne Akt Dawnych in War- century, Stanislaus Augustus Poniatowski, saw (Pl-Wagad), in the Archive of Prince Joseph musical repertoire, musical theatre, music mi- Poniatowski and Maria Teresa Tyszkiewicz- gration Poniatowska. -

Les Opéras De Lully Remaniés Par Rebel Et Francœur Entre 1744 Et 1767 : Héritage Ou Modernité ? Pascal Denécheau

Les opéras de Lully remaniés par Rebel et Francœur entre 1744 et 1767 : héritage ou modernité ? Pascal Denécheau To cite this version: Pascal Denécheau. Les opéras de Lully remaniés par Rebel et Francœur entre 1744 et 1767 : héritage ou modernité ? : Deuxième séminaire de recherche de l’IRPMF : ”La notion d’héritage dans l’histoire de la musique”. 2007. halshs-00437641 HAL Id: halshs-00437641 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00437641 Preprint submitted on 1 Dec 2009 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. P. Denécheau : « Les opéras de Lully remaniés par Rebel et Francœur : héritage ou modernité ? » Les opéras de Lully remaniés par Rebel et Francœur entre 1744 et 1767 : héritage ou modernité ? Une grande partie des œuvres lyriques composées au XVIIe siècle par Lully et ses prédécesseurs ne se sont maintenues au répertoire de l’Opéra de Paris jusqu’à la fin du siècle suivant qu’au prix d’importants remaniements : les scènes jugées trop longues ou sans lien avec l’action principale furent coupées, quelques passages réécrits, un accompagnement de l’orchestre ajouté là où la voix n’était auparavant soutenue que par le continuo. -

Commedia Dell'arte Au

FACULTÉ DE PHILOLOGIE Licence en Langues et Littératures Modernes (Français) L’IMPORTANCE DE LA COMMEDIA DELL’ARTE AU THÉÂTRE DE MOLIÈRE MARÍA BERRIDI PUERTAS TUTEUR : MANUEL GARCÍA MARTÍNEZ SAINT-JACQUES-DE-COMPOSTELLE, ANNéE ACADEMIQUE 2018-2019 FACULTÉ DE PHILOLOGIE Licence en Langues et Littératures Modernes (Français) L’IMPORTANCE DE LA COMMEDIA DELL’ARTE AU THÉÂTRE DE MOLIÈRE MARÍA BERRIDI PUERTAS TUTEUR : MANUEL GARCÍA MARTÍNEZ SAINT-JACQUES-DE-COMPOSTELLE, ANNÉE ACADEMIQUE 2018-2019 2 SOMMAIRE 1. Résumé…………………………………………………………………………………4 2. Introduction……………………………………………………………………………..5 3. De l’introduction de la commedia dell’Arte dans la cour française……………….6 a. Qu’est-ce que c’est la commedia dell’Arte ?............................................6 i. Histoire………………………………………………...……………....6 ii. Caractéristiques essentielles…………………………………….….6 b. Les Guerres d’Italie et les premiers contacts………………………..……..8 i. Les Guerres d’Italie………………………………………………......8 ii. L’introduction de la commedia dell’Arte à la cour française……..9 4. La commedia dell’Arte dans le théâtre français………...………………………...11 a. La comédie française………………………………………………………..11 b. Molière………………………………………………………………………..12 5. La commedia dell’Arte dans la comédie de Molière……………………………...14 a. L’inspiration…………………………………………………………………..14 b. La forme et contenu…………………………………………………..……..17 c. Les masques et l’art visuel………………………………………………….19 i. La disposition scénographique…………………………………….19 ii. Le mélange de genres…………………………………………......20 iii. Les lazzi……………………………………………………………...24 iv. Les masques………………………………………………………...26 1. Personnages inspirés aux masques italiens…………….26 2. Apparitions des masques de la commedia dell’Arte.......27 3. De nouveaux masques……….……………………………27 4. Le multilinguisme……..…………………………………….29 6. Conclusions…………………………………………………………………………...32 7. Bibliographie………………………………………………………………………….34 3 IJNIVERSIOAOF DF SANTIAGO DE COMPOSTElA FACULTADE DE l ,\C.lJL'JAlJL UL I ILUI U:\1,\ rllOLOXfA 2 6 OUT. -

Dossier De Presse

Atypik Films Présente Patrick Ridremont François Berléand Virginie Efira DEAD MAN TALKING Un film belge de PATRICK RIDREMONT (Durée : 1h41) Distribution Relations Presse Atypik Films Laurence Falleur Communication 31 rue des Ombraies 57 rue du Faubourg Montmartre 92000 Nanterre 75009 Paris Eric Boquého Laurence Falleur Assisté de Sandrine Becquart Assisté de Vincent Bayol Et Jacques Domergue Tel : 01.83.92.80.51 Tel : 01.77.68.32.16. Port. : 06.48.89.41.29 Port. : 06.62.49.19.87. [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Matériel de presse téléchargeable sur www.atypikfilms.com SYNOPSIS William Lamers , 40 ans, anonyme criminel condamné au Poison pour meurtre, se prépare à être exécuté. La procédure se passe dans l’indifférence générale et, ni la famille du condamné, ni celle de ses victimes n’a fait le déplacement pour assister à l’exécution. Seul le journaliste d’un minable tabloïd local est venu assister au «spectacle». Pourtant ce qui ne devait être qu’une formalité va rapidement devenir un véritable cauchemar pour Karl Raven, le directeur de la prison. Alors qu’on lui demande s’il a quelque chose à dire avant de mourir, William se met à raconter sa vie, et se lance dans un récit incroyable et bouleversant. Raven s’impatiente et appelle le Gouverneur Brodeck pour obtenir l'autorisation d'exécuter William. Mais comme la loi ne précise rien sur la longueur des dernières paroles et que le Gouverneur Stieg Brodeck, au plus bas dans les sondages, ne peut prendre aucun risque à un mois des élections, on décide de laisser William raconter son histoire jusqu’au bout. -

Course Catalogue 2016 /2017

Course Catalogue 2016 /2017 1 Contents Art, Architecture, Music & Cinema page 3 Arabic 19 Business & Economics 19 Chinese 32 Communication, Culture, Media Studies 33 (including Journalism) Computer Science 53 Education 56 English 57 French 71 Geography 79 German 85 History 89 Italian 101 Latin 102 Law 103 Mathematics & Finance 104 Political Science 107 Psychology 120 Russian 126 Sociology & Anthropology 126 Spanish 128 Tourism 138 2 the diversity of its main players. It will thus establish Art, Architecture, the historical context of this production and to identify the protagonists, before defining the movements that Music & Cinema appear in their pulse. If the development of the course is structured around a chronological continuity, their links and how these trends overlap in reality into each IMPORTANT: ALL OUR ART COURSES ARE other will be raised and studied. TAUGHT IN FRENCH UNLESS OTHERWISE INDICATED COURSE CONTENT : Course Outline: AS1/1b : HISTORY OF CLASSIC CINEMA introduction Fall Semester • Impressionism • Project Genesis Lectures: 2 hours ECTS credits: 3 • "Impressionist" • The Post-Impressionism OBJECTIVE: • The néoimpressionnism To discover the great movements in the history of • The synthetism American and European cinema from 1895 to 1942. • The symbolism • Gauguin and the Nabis PontAven COURSE PROGRAM: • Modern and avantgarde The three cinematic eras: • Fauvism and Expressionism Original: • Cubism - The Lumière brothers : realistic art • Futurism - Mélies : the beginnings of illusion • Abstraction Avant-garde : - Expressionism -

Stéphane Braunschweig Théâtre De L'odéon- 6E

de Molière 17 septembre 25 octobre 2008 mise en scène & scénographie Stéphane Braunschweig Théâtre de l'Odéon- 6e costumes Thibault Vancraenenbroeck lumière Marion Hewlett son Xavier Jacquot collaboration artistique Anne-Françoise Benhamou collaboration à la scénographie Alexandre de Darden production Théâtre national de Strasbourg créé le 29 avril 2008 au Théâtre national de Strasbourg avec Monsieur Loyal : Jean-Pierre Bagot Cléante : Christophe Brault Tartuffe : Clément Bresson Valère : Thomas Condemine Orgon : Claude Duparfait Mariane : Julie Lesgages Elmire : Pauline Lorillard Dorine : Annie Mercier Damis : Sébastien Pouderoux Madame Pernelle : Claire Wauthion et avec la participation de l’exempt : François Loriquet Rencontre Spectacle du mardi au samedi à 20h, le dimanche à 15h, relâche le lundi Au bord de plateau jeudi 2 octobre Prix des places : 30€ - 22€ - 12€ - 7,50€ (séries 1, 2, 3, 4) à l’issue de la représentation, Tarif groupes scolaires : 11€ et 6€ (séries 2 et 3) en présence de l’équipe artistique. Entrée libre. Odéon–Théâtre de l’Europe Théâtre de l’Odéon Renseignements 01 44 85 40 90 e Place de l’Odéon Paris 6 / Métro Odéon - RER B Luxembourg L’équipe des relations avec le public : Scolaires et universitaires, associations d’étudiants Réservation et Actions pédagogiques Christophe Teillout 01 44 85 40 39 - [email protected] Emilie Dauriac 01 44 85 40 33 - [email protected] Dossier également disponible sur www.theatre-odeon.fr Certaines parties de ce dossier sont tirées du dossier pédagogique et du programme réalisés par l’équipe du Théâtre national de Strasbourg. Collaboration d’Arthur Le Stanc Tartuffe / 17 septembre › 25 octobre 2008 1 Oui, je deviens tout autre avec son entretien, Il m'enseigne à n'avoir affection pour rien ; De toutes amitiés il détache mon âme ; Et je verrais mourir frère, enfants, mère, et femme, Que je m'en soucierais autant que de cela. -

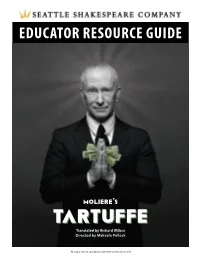

Translated by Richard Wilbur Directed by Makaela Pollock

Translated by Richard Wilbur Directed by Makaela Pollock All original material copyright © Seattle Shakespeare Company 2015 WELCOME Dear Educators, Tartuffe is a wonderful play, and can be great for students. Its major themes of hypocrisy and gullibility provide excellent prompts for good in-class discussions. Who are the “Tartuffes” in our 21st century world? What can you do to avoid being fooled the way Orgon was? Tartuffe also has some challenges that are best to discuss with students ahead of time. Its portrayal of religion as the source of Tartuffe’s hypocrisy angered priests and the deeply religious when it was first written, which led to the play being banned for years. For his part, Molière always said that the purpose of Tartuffe was not to lampoon religion, but to show how hypocrisy comes in many forms, and people should beware of religious hypocrisy among others. There is also a challenging scene between Tartuffe and Elmire at the climax of the play (and the end of Orgon’s acceptance of Tartuffe). When Tartuffe attempts to seduce Elmire, it is up to the director as to how far he gets in his amorous attempts, and in our production he gets pretty far! This can also provide an excellent opportunity to talk with students about staunch “family values” politicians who are revealed to have had affairs, the safety of women in today’s society, and even sexual assault, depending on the age of the students. Molière’s satire still rings true today, and shows how some societal problems have not been solved, but have simply evolved into today’s context. -

Download Teachers' Notes

Teachers’ Notes Researched and Compiled by Michele Chigwidden Teacher’s Notes Adelaide Festival Centre has contributed to the development and publication of these teachers’ notes through its education program, CentrED. Brink Productions’ by Molière A new adaptation by Paul Galloway Directed by Chris Drummond INTRODUCTION Le Malade imaginaire or The Hypochondriac by French playwright Molière, was written in 1673. Today Molière is considered one of the greatest masters of comedy in Western literature and his work influences comedians and dramatists the world over1. This play is set in the home of Argan, a wealthy hypochondriac, who is as obsessed with his bowel movements as he is with his mounting medical bills. Argan arranges for Angélique, his daughter, to marry his doctor’s nephew to get free medical care. The problem is that Angélique has fallen in love with someone else. Meanwhile Argan’s wife Béline (Angélique’s step mother) is after Argan’s money, while their maid Toinette is playing havoc with everyone’s plans in an effort to make it all right. Molière’s timeless satirical comedy lampoons the foibles of people who will do anything to escape their fear of mortality; the hysterical leaps of faith and self-delusion that, ironically, make us so susceptible to the quackery that remains apparent today. Brink’s adaptation, by Paul Galloway, makes Molière’s comedy even more accessible, and together with Chris Drummond’s direction, the brilliant ensemble cast and design team, creates a playful immediacy for contemporary audiences. These teachers’ notes will provide information on Brink Productions along with background notes on the creative team, cast and a synopsis of The Hypochondriac. -

The Use of the Polish Folk Music Elements and the Fantasy Elements in the Polish Fantasy on Original Themes In

THE USE OF THE POLISH FOLK MUSIC ELEMENTS AND THE FANTASY ELEMENTS IN THE POLISH FANTASY ON ORIGINAL THEMES IN G-SHARP MINOR FOR PIANO AND ORCHESTRA OPUS 19 BY IGNACY JAN PADEREWSKI Yun Jung Choi, B.A., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2007 APPROVED: Adam Wodnicki, Major Professor Jeffrey Snider, Minor Professor Joseph Banowetz, Committee Member Graham Phipps, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music James C. Scott, Dean of the College of Music Sandra L. Terrell, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Choi, Yun Jung, The Use of the Polish Folk Music Elements and the Fantasy Elements in the Polish Fantasy on Original Themes in G-sharp Minor for Piano and Orchestra, Opus 19 by Ignacy Jan Paderewski. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2007, 105 pp., 5 tables, 65 examples, references, 97 titles. The primary purpose of this study is to address performance issues in the Polish Fantasy, Op. 19, by examining characteristics of Polish folk dances and how they are incorporated in this unique work by Paderewski. The study includes a comprehensive history of the fantasy in order to understand how Paderewski used various codified generic aspects of the solo piano fantasy, as well as those of the one-movement concerto introduced by nineteenth-century composers such as Weber and Liszt. Given that the Polish Fantasy, Op. 19, as well as most of Paderewski’s compositions, have been performed more frequently in the last twenty years, an analysis of the combination of the three characteristic aspects of the Polish Fantasy, Op.19 - Polish folk music, the generic rhetoric of a fantasy and the one- movement concerto - would aid scholars and performers alike in better understanding the composition’s engagement with various traditions and how best to make decisions about those traditions when approaching the work in a concert setting. -

A European Singspiel

Columbus State University CSU ePress Theses and Dissertations Student Publications 2012 Die Zauberflöte: A urE opean Singspiel Zachary Bryant Columbus State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://csuepress.columbusstate.edu/theses_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Bryant, Zachary, "Die Zauberflöte: A urE opean Singspiel" (2012). Theses and Dissertations. 116. https://csuepress.columbusstate.edu/theses_dissertations/116 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Publications at CSU ePress. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CSU ePress. r DIE ZAUBEFL5TE: A EUROPEAN SINGSPIEL Zachary Bryant Die Zauberflote: A European Singspiel by Zachary Bryant A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of Requirements of the CSU Honors Program for Honors in the Bachelor of Arts in Music College of the Arts Columbus State University Thesis Advisor JfAAlj LtKMrkZny Date TttZfQjQ/Aj Committee Member /1^^^^^^^C^ZL^>>^AUJJ^AJ (?YUI£^"QdJu**)^-) Date ^- /-/<£ Director, Honors Program^fSs^^/O ^J- 7^—^ Date W3//±- Through modern-day globalization, the cultures of the world are shared on a daily basis and are integrated into the lives of nearly every person. This reality seems to go unnoticed by most, but the fact remains that many individuals and their societies have formed a cultural identity from the combination of many foreign influences. Such a multicultural identity can be seen particularly in music. Composers, artists, and performers alike frequently seek to incorporate separate elements of style in their own identity. One of the earliest examples of this tradition is the German Singspiel.