Managing Lakes and Their Basins for Sustainable

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hydrobiological Assessment of the Zambezi River System: a Review

WORKING PAPER HYDROBIOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT OF THE ZAMBEZI RWER SYSTEM: A REVIEW September 1988 W P-88-089 lnlernai~onallnsl~iule for Appl~rdSysiems Analysis HYDROBIOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT OF THE ZAMBEZI RIVER SYSTEM: A REVIEW September 1988 W P-88-089 Working Papers are interim reports on work of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis and have received only limited review. Views or opinions expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of the Institute or of its National Member Organizations. INTERNATIONAL INSTITUTE FOR APPLIED SYSTEMS ANALYSIS A-2361 Laxenburg, Austria One of the Lmporhnt Projects within the Environment Program is that entitled: De- *on apport *stems jbr Mancrgfnq Lurge Intemartiorrcrl Rivers. Funded by the Ford Foundation, UNEP, and CNRS France, the Project includes two case stu- dies focused on the Danube and the Zambezi river basins. The author of this report, Dr. G. Pinay, joined IIASA in February 1987 after completing his PhD at the Centre dSEmlogie des Ressources Renouvelables in Toulouse. Dr. Pinny was assigned the task of reviewing the published literature on water management issues in the Zambezi river basin, and related ecological ques- tions. At the outset, I thought that a literature review on the Zambezi river basin would be a rather slim report. I am therefore greatly impressed with this Working Paper, which includes a large number of references but more importantly, syn- thesizes the various studies and provides the scientific basis for investigating a very complex set of management issues. Dr. Pinay's review will be a basic refer- ence for further water management studies in the Zambezi river basin. -

Final Report for WWF

Intermediate Technology Consultants Ltd Final Report for WWF The Mphanda Nkuwa Dam project: Is it the best option for Mozambique’s energy needs? June 2004 WWF Mphanda Nkuwa Dam Final Report ITC Table of Contents 1 General Background.............................................................................................................................6 1.1 Mozambique .................................................................................................................................6 1.2 Energy and Poverty Statistics .....................................................................................................8 1.3 Poverty context in Mozambique .................................................................................................8 1.4 Energy and cross-sectoral linkages to poverty ........................................................................11 1.5 Mozambique Electricity Sector.................................................................................................12 2 Regional Electricity Market................................................................................................................16 2.1 Southern Africa Power Pool......................................................................................................16 3 Energy Needs.......................................................................................................................................19 3.1 Load Forecasts............................................................................................................................19 -

Consequences of Drying Lake Systems Around the World

Consequences of Drying Lake Systems around the World Prepared for: State of Utah Great Salt Lake Advisory Council Prepared by: AECOM February 15, 2019 Consequences of Drying Lake Systems around the World Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................... 5 I. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................... 13 II. CONTEXT ................................................................................. 13 III. APPROACH ............................................................................. 16 IV. CASE STUDIES OF DRYING LAKE SYSTEMS ...................... 17 1. LAKE URMIA ..................................................................................................... 17 a) Overview of Lake Characteristics .................................................................... 18 b) Economic Consequences ............................................................................... 19 c) Social Consequences ..................................................................................... 20 d) Environmental Consequences ........................................................................ 21 e) Relevance to Great Salt Lake ......................................................................... 21 2. ARAL SEA ........................................................................................................ 22 a) Overview of Lake Characteristics .................................................................... 22 b) Economic -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 113 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 113 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 160 WASHINGTON, THURSDAY, JANUARY 30, 2014 No. 18 House of Representatives The House was not in session today. Its next meeting will be held on Friday, January 31, 2014, at 3 p.m. Senate THURSDAY, JANUARY 30, 2014 The Senate met at 10 a.m. and was to the Senate from the President pro ahead, and I think it is safe to say that called to order by the Honorable CHRIS- tempore (Mr. LEAHY). despite the hype, there was not a whole TOPHER MURPHY, a Senator from the The legislative clerk read the fol- lot in this year’s State of the Union State of Connecticut. lowing letter: that would do much to alleviate the U.S. SENATE, concerns and anxieties of most Ameri- PRAYER PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE, cans. There was not anything in there The Chaplain, Dr. Barry C. Black, of- Washington, DC, January 30, 2014. that would really address the kind of fered the following prayer: To the Senate: dramatic wage stagnation we have seen Let us pray. Under the provisions of rule I, paragraph 3, over the past several years among the Eternal Spirit, we don’t know all of the Standing Rules of the Senate, I hereby middle class or the increasingly dif- appoint the Honorable CHRISTOPHER MURPHY, that this day holds, but we know that a Senator from the State of Connecticut, to ficult situation people find themselves You hold this day in Your sovereign perform the duties of the Chair. -

Illustrated and Descriptive Catalogue and Price List of Stereopticons

—. ; I, £3,v; and Descriptive , Illustrated ;w j CATALOGUE AND PRICE LIST- t&fs — r~* yv4 • .'../-.it *.•:.< : .. 4^. ; • ’• • • wjv* r,.^ N •’«* - . of . - VJ r .. « 7 **: „ S ; \ 1 ’ ; «•»'•: V. .c; ^ . \sK? *• .* Stereopticons . * ' «». .. • ” J- r . .. itzsg' Lantern Slides 1 -f ~ Accessories for Projection Stereopticon and Film Exchange W. B. MOORE, Manager. j. :rnu J ; 104 to no Franlclin Street ‘ Washington . (Cor. CHICAGO INDEX TO LANTERNS, ETC. FOR INDEX TO SLIDES SEE INDEX AT CLOSE OF CATALOGUE. Page Acetylene Dissolver 28 Champion Lantern 3g to 42 “ Gas 60 Check Valve S3 •* 1 • .• Gas Burner.... ; 19 Chemicals, Oxygen 74, 81 ** < .' I j Gas Generator.. ; 61 to 66 Chirograph 136 “ Gas Generator, Perfection to 66 64 Chlorate of Potash, tee Oxygen Chemicals 74 Adapter from to sire lenses, see Chromatrope.... 164 Miscellaneous....... 174 Cloak, How Made 151 Advertising Slides, Blank, see Miscellaneous.. 174 ** Slides 38010,387 " Slides 144 Color Slides or Tinters .^140 “ Slides, Ink for Writing, see Colored Films 297 Miscellaneous, 174 Coloring Films 134 “ Posters * *...153 " Slides Alcohol Vapor Mantle Light 20A v 147 Combined Check or Safety Valve 83 Alternating.Carbons, Special... 139 Comic and Mysterious Films 155 Allen Universal Focusing Lens 124, 125 Comparison of Portable Gas Outfits 93, 94 America, Wonders cf Description, 148 “Condensing Lens 128 Amet's Oro-Carbi Light 86 to 92, 94 " Lens Mounting 128 •Ancient Costumes ....! 131 Connections, Electric Lamp and Rheostat... 96, 97 Approximate Length of Focus 123 " Electric Stage 139 Arc Lamp 13 to 16 Costumes 130 to 152, 380 to 3S7 ** Lamp and Rheostat, How to Connect 96 Cover Glasses, see Miscellaneous ,....174 Arnold's Improved Calcium Light Outfit. -

Cahora Bassa North Bank Hydropower Project

Hydropower Sustainability Assessment Protocol: Cahora Bassa North Bank Hydropower Project Cahora Bassa North Bank Hydropower Project Public Disclosure Authorized Hidroeléctrica de Cahora Bassa Public Disclosure Authorized Zambezi River Basin Introduction The hydropower resources of the Zambezi River Basin are central to sustaining economic development and prosperity across southern Africa. The combined GDP among the riparian states is estimated at over US$100 billion. With recognition of the importance of shared prosperity and increasing commitments toward regional integration, there is significant potential for collective development of the region’s rich natural endowments. Despite this increasing prosperity, Contents however, poverty is persistent across the basin and coefficients of inequality for some of the riparian states are among the highest in Introduction .......................................................................................... 1 the world. Public Disclosure Authorized The Hydropower Sustainability Assessment Protocol ......................... 4 Reflecting the dual nature of the regional economy, new investments The Project ............................................................................................ 3 in large infrastructure co-exist alongside a parallel, subsistence economy that is reliant upon environmental services provided by the The Process ........................................................................................... 8 river. Appropriate measures are therefore needed to balance -

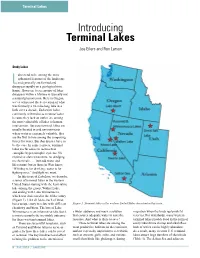

Introducing Terminal Lakes Joe Eilers and Ron Larson

Terminal Lakes Introducing Terminal Lakes Joe Eilers and Ron Larson Study Lakes akes tend to be among the more ephemeral features of the landscape Land generally are formed and disappear rapidly on a geological time frame. However, to see groups of lakes disappear within a lifetime is typically not a natural phenomenon. Here in Oregon, we’ve witnessed the desiccation of what was formerly a 16-mile-long lake in a little over a decade. Endorehic lakes, commonly referred to as terminal lakes because they lack an outlet, are among the most vulnerable of lakes to human intervention. Because terminal lakes are usually located in arid environments where water is extremely valuable, they are the first to lose among the competing forces for water. But that doesn’t have to be the case. In some respects, terminal lakes are far easier to restore than eutrophic/hypereutrophic systems. No expensive alum treatments, no dredging, no chemicals . just add water and life returns: but as those in West know, “Whiskey is for drinking; water is for fighting over.” And fight we must. In this issue of LakeLine, we describe a series of terminal lakes in the western United States starting with the least saline lake among the group, Walker Lake, and ending with Lake Winnemucca, which was desiccated in the 20th century (Figure 1). Like all lakes, each of these has a unique story to relate with different Figure 1. Terminal lakes in the western United States described in this issue. chemistry and biota. The loss of Lake Winnemucca is an informative tale, but it a wider audience and reach a solution migration when the birds replenish fat is not necessarily the inevitable outcome that ensures adequate water to save the reserves. -

Press Release HCB ANNOUNCES the IPO of up to 7.5% of ITS SHARES on the MOZAMBICAN STOCK EXCHANGE

Press Release HCB ANNOUNCES THE IPO OF UP TO 7.5% OF ITS SHARES ON THE MOZAMBICAN STOCK EXCHANGE • HCB is the concessionaire of the largest hydroelectric power plant in southern Africa, located in Songo, Northern Mozambique • Listing planned for July 2019 with shares offered to Mozambican nationals, companies and institutional investors at 3 Meticais per share • Vision of reach and inclusion to be achieved through innovative nationwide multibank distribution channels, mobile app and USSD platform Maputo, 21 May 2019 Hidroeléctrica de Cahora Bassa (HCB), the Mozambican concessionaire of the Cahora Bassa hydroelectric plant, the largest in southern Africa, yesterday launched its Initial Public Offer (IPO) for up to 7.5% of its shares to individual Mozambicans, national companies and institutional investors. The IPO will see a first tranche of 2.5% of its shares becoming available on the Mozambican stock exchange - Bolsa de Valores de Moçambique (“BVM”). HCB shares will be sold at 3 Meticais each with the subscription period taking place between 17 June and 12 July 2019. Nationwide roadshows and innovative channels have been created to ensure maximum reach and inclusion. Individuals will be able to place purchase orders through various Mozambican banks’ branch networks but also through a USSD mobile application, a mobile app and via internet banking. The Consortium BCI-BiG (BCI and BIG are two Mozambican banks), are the global coordinators for this IPO with other financial institutions supporting the placement of the shares through their branch networks. Maputo Office Head Office: Edifício JAT I – Av. 25 de Setembro, 420 – 6th Floor PO Box – 263 – Songo PO Box: 4120 PBX: +258 252 82221/4 | Fax: +258 252 82220 PBX: +258 21 350700| Fax: +258 21 314147 Pág. -

Nutrient Dynamics in the Jordan River and Great

NUTRIENT DYNAMICS IN THE JORDAN RIVER AND GREAT SALT LAKE WETLANDS by Shaikha Binte Abedin A thesis submitted to the faculty of The University of Utah in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering The University of Utah August 2016 Copyright © Shaikha Binte Abedin 2016 All Rights Reserved The University of Utah Graduate School STATEMENT OF THESIS APPROVAL The thesis of Shaikha Binte Abedin has been approved by the following supervisory committee members: Ramesh K. Goel , Chair 03/08/2016 Date Approved Michael E. Barber , Member 03/08/2016 Date Approved Steven J. Burian , Member 03/08/2016 Date Approved and by Michael E. Barber , Chair/Dean of the Department/College/School of Civil and Environmental Engineering and by David B. Kieda, Dean of The Graduate School. ABSTRACT In an era of growing urbanization, anthropological changes like hydraulic modification and industrial pollutant discharge have caused a variety of ailments to urban rivers, which include organic matter and nutrient enrichment, loss of biodiversity, and chronically low dissolved oxygen concentrations. Utah’s Jordan River is no exception, with nitrogen contamination, persistently low oxygen concentration and high organic matter being among the major current issues. The purpose of this research was to look into the nitrogen and oxygen dynamics at selected sites along the Jordan River and wetlands associated with Great Salt Lake (GSL). To demonstrate these dynamics, sediment oxygen demand (SOD) and nutrient flux experiments were conducted twice through the summer, 2015. The SOD ranged from 2.4 to 2.9 g-DO m-2 day-1 in Jordan River sediments, whereas at wetland sites, the SOD was as high as 11.8 g-DO m-2 day-1. -

The Storstrd Responsible Have a New on Board Tenyo, Third Officer of Collier , Sugar Story Say Adherents Blamed for Wreck of The

From San Franctsco: Sonoma. July 13. For San Francisco i 3:30 Nippon Maru. July 14. From Vancouver: Makura, July 15. For Vancouver: i l Niagara, July 14. liJ Editio KvenliiK Bulletin. Kst. 18S2. No. ',903 20 --HONOLULU, TERRITORY OP HAWAII, JULY 11, 1911. 20 PAGES PRICE FIVE CENTS Hawaiian Star, Vol. XXII. No. 6942 PAGES SATURDAY, DEMOCRATS DR. SUN TAT SEN COMMISSION KINDS THE STORSTRD RESPONSIBLE HAVE A NEW ON BOARD TENYO, THIRD OFFICER OF COLLIER , SUGAR STORY SAY ADHERENTS BLAMED FOR WRECK OF THE McCandless ..Campaign on Whereabsuts of First Provi Declaration ' That Local sional President Mooted LINER EMPRESS OF IRELAND Question Republicans Refused to Among Chinese Accept Tariff a MAY RE EN ROUTE TO Failure to Call Captain Anderson When Fog Settled Over Compromise MAINLAND AFTER FUNDS Vessel, Given as Reason for Collision in St. Lawrence -- ,.. y-:-v VETERAN CANDIDATE Local Member of Young China River That Brought Death to Almost 1000 on Night ot SURE TO RUN AGAIN of -- Investigation Board Party ""'I J?- - " May 28 Lord Mersey Member Positive Leader Was A fym Iff 4. ' Aboard Japanese Liner ' --' Makes Informal Announcement 11 . v Associated Press servlr by Federal Wireless. ?2&i&e9E&- - No Statement Whether Did Dr. Sun Vat Sen. in the d sguise QUEBEC, Canada, July 11- - The commission appointed to make a Bourbons -- Indorse Duty of a lo!y cooUe, pass through Hono- thorough' investigation of the sinking of the S, S. Empress of Ireland, in the lulu Thus1ay as a st?erago passen- St Lawrence river ht night of May 23, has placed the responsibility for ger Toyo Informal announcement of his can- in the K!sn Kaisha liner the disaster upon the Norwegian collier Storstad. -

Motion to Re-Open Hearings for Reactors Where Hearings Had

United States of America Nuclear Regulatory Commission Before the Atomic Safety and Licensing Board In the Matter of ) Progress Energy Florida, Inc. ) Docket Nos. 52-029-COL (Levy County Nuclear Power Plant, ) and 52-030-COL Units 1 and 2) ) September 29, 2014 ECOLOGY PARTY OF FLORIDA AND NUCLEAR INFORMATION AND RESOURCE SERVICES’ MOTION TO REOPEN THE RECORD I. INTRODUCTION Pursuant to 10 C.F.R. § 2.326, the Ecology Party of Florida and Nuclear Information and Resource Service (“Petitioners”) hereby move to reopen the record in this proceeding to admit a new Contention challenging the failure of the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (“NRC”) to make predictive safety findings in this combined license proceeding regarding the disposal of nuclear waste.1 Petitioners respectfully submit that reopening the record and admitting the new contention is necessary to ensure that the NRC fulfills its statutory obligation under the Atomic Energy Act (“AEA”) to protect public health and safety from the risks posed by irradiated reactor fuel generated during the reactor’s license term. Several overlapping factors, set forth in three regulations, govern motions to reopen and admit new contentions. This motion and the accompanying Contention satisfy each of these factors. See 10 C.F.R. §§ 2.309(c), 2.323, and 2.326. This motion is supported by the expert declarations of Dr. Arjun Makhijani and Mark Cooper. It is also supported by the standing declarations of Emily Casey, David McSherry and December McSherry (the Ecology Party); and Amanda Hancock Anderson and W. Russell Anderson (NIRS). 1 The Contention, entitled “Failure to Make Atomic Energy Act-Required Safety Findings Regarding Spent Fuel Disposal Feasibility and Capacity,” is attached and incorporated by reference. -

Mozambique Case Study Example1

Mozambique Case study example1 - Principle 1: The Zambezi River Basin - "dialogue for building a common vision" The Zambezi River Basin encompasses some 1.300 km2 throughout the Southern African Development Community (SADC) region, including a dense network of tributaries and associated wetland systems in eight countries (Angola, Namibia, Botswana, Zimbabwe, Zambia, Malawi, Tanzania, Mozambique). The livelihoods of approximately 26 million people are directly dependent on this basin, deriving benefits from its water, hydro-electric power, irrigation developments, fisheries and great wealth of related natural resources, including grazing areas, wildlife, and tourism. Over the past forty years, however, the communities and ecosystems of the lower Zambezi have been constraint by the management of large upstream dams. The toll is particularly high on Mozambique, as it the last country on the journey of the Zambezi; Mozambicans have to live with the consequences of upriver management. By eliminating natural flooding and greatly increasing dry season flows in the lower Zambezi, Kariba Dam (completed in 1959) and especially Cahora Bassa Dam (completed in 1974) cause great hardship for hundreds of thousands of Mozambican villagers whose livelihoods depend on the ebb and flow of the Zambezi River. Although these hydropower dams generate important revenues and support development however, at the expense of other resource users. Subsistence fishing, farming, and livestock grazing activities have collapsed with the loss of the annual flood. The productivity of the prawn fishery has declined by $10 - 20 million per year -- this in a country that ranks as one of the world’s poorest nations (per capita income in 2000 was USD230).