Extension in Mona Passage, Northeast Caribbean

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Search of the Extinct Hutia in Cave Deposits of Isla De Mona, P.R. by Ángel M

In Search of the Extinct Hutia in Cave Deposits of Isla de Mona, P.R. by Ángel M. Nieves-Rivera, M.S. and Donald A. McFarlane, Ph.D. Isolobodon portoricensis, the extinct have been domesticated, and its abundant (14C) date was obtained on charcoal and Puerto Rican hutia (a large guinea-pig like remains in kitchen middens indicate that it bone fragments from Cueva Negra, rodent), was about the size of the surviving formed part of the diet for the early settlers associated with hutia bones (Frank, 1998). Hispaniolan hutia Plagiodontia (Rodentia: (Nowak, 1991; Flemming and MacPhee, This analysis yielded an uncorrected 14C age Capromydae). Isolobodon portoricensis was 1999). This species of hutia was extinct, of 380 ±60 before present, and a corrected originally reported from Cueva Ceiba (next apparently shortly after the coming of calendar age of 1525 AD, (1 sigma range to Utuado, P.R.) in 1916 by J. A. Allen (1916), European explorers, according to most 1480-1655 AD). This date coincides with the and it is known today only by skeletal remains historians. final occupation of Isla de Mona by the Taino from Hispaniola (Dominican Republic, Haiti, The first person to take an interest in the Indians (1578 AD; Wadsworth 1977). The Île de la Gonâve, ÎIe de la Tortue), Puerto faunal remains of the caves of Isla de Mona purpose of this article is to report some new Rico (mainland, Isla de Mona, Caja de was mammalogist Harold E. Anthony, who paleontological discoveries of the Puerto Muertos, Vieques), the Virgin Islands (St. in 1926 collected the first Puerto Rican hutia Rican hutia in cave deposits of Isla de Mona Croix, St. -

Two New Scorpions from the Puerto Rican Island of Vieques, Greater Antilles (Scorpiones: Buthidae)

Two new scorpions from the Puerto Rican island of Vieques, Greater Antilles (Scorpiones: Buthidae) Rolando Teruel, Mel J. Rivera & Carlos J. Santos September 2015 — No. 208 Euscorpius Occasional Publications in Scorpiology EDITOR: Victor Fet, Marshall University, ‘[email protected]’ ASSOCIATE EDITOR: Michael E. Soleglad, ‘[email protected]’ Euscorpius is the first research publication completely devoted to scorpions (Arachnida: Scorpiones). Euscorpius takes advantage of the rapidly evolving medium of quick online publication, at the same time maintaining high research standards for the burgeoning field of scorpion science (scorpiology). Euscorpius is an expedient and viable medium for the publication of serious papers in scorpiology, including (but not limited to): systematics, evolution, ecology, biogeography, and general biology of scorpions. Review papers, descriptions of new taxa, faunistic surveys, lists of museum collections, and book reviews are welcome. Derivatio Nominis The name Euscorpius Thorell, 1876 refers to the most common genus of scorpions in the Mediterranean region and southern Europe (family Euscorpiidae). Euscorpius is located at: http://www.science.marshall.edu/fet/Euscorpius (Marshall University, Huntington, West Virginia 25755-2510, USA) ICZN COMPLIANCE OF ELECTRONIC PUBLICATIONS: Electronic (“e-only”) publications are fully compliant with ICZN (International Code of Zoological Nomenclature) (i.e. for the purposes of new names and new nomenclatural acts) when properly archived and registered. All Euscorpius issues starting from No. 156 (2013) are archived in two electronic archives: Biotaxa, http://biotaxa.org/Euscorpius (ICZN-approved and ZooBank-enabled) Marshall Digital Scholar, http://mds.marshall.edu/euscorpius/. (This website also archives all Euscorpius issues previously published on CD-ROMs.) Between 2000 and 2013, ICZN did not accept online texts as "published work" (Article 9.8). -

Chronology of Major Caribbean Earthquakes by Dr

Chronology of Major Caribbean Earthquakes By Dr. Frank J. Collazo February 4, 2010 Seismic Activity in the Caribbean Area The image above represents the earthquake activity for the past seven days in Puerto Rico (roughly Jan 8-15, 2010). As you can see there are quite a few recorded. In fact, the Puerto Rico Seismic Network has registered around 80 earthquake tremors in the first 15 days of 2010. Thankfully for Puerto Rico, these are usually on the lower end of the scale, but they are felt around the island. In fact, while being on the island, I actually felt two earthquakes, one of which was the 7.4 magnitude Martinique earthquake back in November 2007. The following is a chronology of the major earthquakes in the Caribbean basin: 1615: Earthquake in the Dominican Republic that caused damages in Puerto Rico. 1670: Damages in San Germán and San Juan (MJ). A strong earthquake, whose magnitude has not been determined, occurred in 1670, significantly affecting the area of San German District. 1692: Jamaica Fatalities 2,000. Level of damages is unknown. 1717: Church San Felipe in Arecibo and the parochial house in San Germán were destroyed (A). 1740: The Church of Guadalupe in Villa de Ponce was destroyed (A). Intensity VII, there is only information from Ponce that the earthquake was felt, absence of information of San Germán and the information of Yauco and Lajas suggest a superficial earthquake near to Ponce (G). 1787: Possibly the strongest earthquake that has affected Puerto Rico since the beginning of colonization. This was felt strongly throughout the Island and may have been as large as magnitude 8.0 on the Richter Scale. -

ATOLL RESEARCH BULLETIN NO. 251 BIOGEOGRAPHY of the PUERTO RICAN BANK by Harold Heatwole, Richard Levins and Michael D. Byer

ATOLL RESEARCH BULLETIN NO. 251 BIOGEOGRAPHY OF THE PUERTO RICAN BANK by Harold Heatwole, Richard Levins and Michael D. Byer Issued by THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Washington, D. C., U.S.A. July 1981 VIRGIN ISLANDS CULEBRA PUERTO RlCO Fig. 1. Map of the Puerto Rican Island Shelf. Rectangles A - E indicate boundaries of maps presented in more detail in Appendix I. 1. Cayo Santiago, 2. Cayo Batata, 3. Cayo de Afuera, 4. Cayo de Tierra, 5. Cardona Key, 6. Protestant Key, 7. Green Key (st. ~roix), 8. Caiia Azul ATOLL RESEARCH BULLETIN 251 ERRATUM The following caption should be inserted for figure 7: Fig. 7. Temperature in and near a small clump of vegetation on Cayo Ahogado. Dots: 5 cm deep in soil under clump. Circles: 1 cm deep in soil under clump. Triangles: Soil surface under clump. Squares: Surface of vegetation. X's: Air at center of clump. Broken line indicates intervals of more than one hour between measurements. BIOGEOGRAPHY OF THE PUERTO RICAN BANK by Harold Heatwolel, Richard Levins2 and Michael D. Byer3 INTRODUCTION There has been a recent surge of interest in the biogeography of archipelagoes owing to a reinterpretation of classical concepts of evolution of insular populations, factors controlling numbers of species on islands, and the dynamics of inter-island dispersal. The literature on these subjects is rapidly accumulating; general reviews are presented by Mayr (1963) , and Baker and Stebbins (1965) . Carlquist (1965, 1974), Preston (1962 a, b), ~ac~rthurand Wilson (1963, 1967) , MacArthur et al. (1973) , Hamilton and Rubinoff (1963, 1967), Hamilton et al. (1963) , Crowell (19641, Johnson (1975) , Whitehead and Jones (1969), Simberloff (1969, 19701, Simberloff and Wilson (1969), Wilson and Taylor (19671, Carson (1970), Heatwole and Levins (1973) , Abbott (1974) , Johnson and Raven (1973) and Lynch and Johnson (1974), have provided major impetuses through theoretical and/ or general papers on numbers of species on islands and the dynamics of insular biogeography and evolution. -

Us Caribbean Regional Coral Reef Fisheries Management Workshop

Caribbean Regional Workshop on Coral Reef Fisheries Management: Collaboration on Successful Management, Enforcement and Education Methods st September 30 - October 1 , 2002 Caribe Hilton Hotel San Juan, Puerto Rico Workshop Objective: The regional workshop allowed island resource managers, fisheries educators and enforcement personnel in Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands to identify successful coral reef fishery management approaches. The workshop provided the U.S. Coral Reef Task Force with recommendations by local, regional and national stakeholders, to develop more effective and appropriate regional planning for coral reef fisheries conservation and sustainable use. The recommended priorities will assist Federal agencies to provide more directed grant and technical assistance to the U.S. Caribbean. Background: Coral reefs and associated habitats provide important commercial, recreational and subsistence fishery resources in the United States and around the world. Fishing also plays a central social and cultural role in many island communities. However, these fishery resources and the ecosystems that support them are under increasing threat from overfishing, recreational use, and developmental impacts. This workshop, held in conjunction with the U.S. Coral Reef Task Force Meeting, brought together island resource managers, fisheries educators and enforcement personnel to compare methods that have been successful, including regulations that have worked, effective enforcement, and education to reach people who can really effect change. These efforts were supported by Federal fishery managers and scientists, Puerto Rico Sea Grant, and drew on the experience of researchers working in the islands and Florida. The workshop helped develop approaches for effective fishery management strategies in the U.S. Caribbean and recommended priority actions to the U.S. -

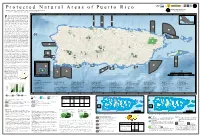

Protected Areas by Management 9

Unted States p Forest Department a Service DRNA of Agriculture g P r o t e c t e d N a t u r a l A r e a s o f P u e r to R i c o K E E P I N G C O M M ON S P E C I E S C O M M O N PRGAP ANALYSIS PROJECT William A. Gould, Maya Quiñones, Mariano Solórzano, Waldemar Alcobas, and Caryl Alarcón IITF GIS and Remote Sensing Lab A center for tropical landscape analysis U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, International Institute of Tropical Forestry . o c 67°30'0"W 67°20'0"W 67°10'0"W 67°0'0"W 66°50'0"W 66°40'0"W 66°30'0"W 66°20'0"W 66°10'0"W 66°0'0"W 65°50'0"W 65°40'0"W 65°30'0"W 65°20'0"W i R o t rotection of natural areas is essential to conserving biodiversity and r e u P maintaining ecosystem services. Benefits and services provided by natural United , Protected areas by management 9 States 1 areas are complex, interwoven, life-sustaining, and necessary for a healthy A t l a n t i c O c e a n 1 1 - 6 environment and a sustainable future (Daily et al. 1997). They include 2 9 0 clean water and air, sustainable wildlife populations and habitats, stable slopes, The Bahamas 0 P ccccccc R P productive soils, genetic reservoirs, recreational opportunities, and spiritual refugia. -

Predictability of Non-Phase-Locked Baroclinic Tides in the Caribbean Sea Edward D

Predictability of Non-Phase-Locked Baroclinic Tides in the Caribbean Sea Edward D. Zaron1 1Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Portland State University, Portland, Oregon, USA Correspondence: E. D. Zaron ([email protected]) Abstract. The predictability of the sea surface height expression of baroclinic tides is examined with 96 hr forecasts pro- duced by the AMSEAS operational forecast model during 2013–2014. The phase-locked tide, both barotropic and baroclinic, is identified by harmonic analysis of the 2 year record and found to agree well with observations from tide gauges and satellite altimetry within the Caribbean Sea. The non-phase-locked baroclinic tide, which is created by time-variable mesoscale strati- 5 fication and currents, may be identified from residual sea level anomalies (SLAs) near the tidal frequencies. The predictability of the non-phase-locked tide is assessed by measuring the difference between a forecast – centered at T + 36 hr, T + 60 hr, or T + 84 hr – and the model’s later verifying analysis for the same time. Within the Caribbean Sea, where a baroclinic tidal sea level range of ±5 cm is typical, the forecast error for the non-phase-locked tidal SLA is correlated with the forecast error for the sub-tidal (mesoscale) SLA. Root-mean-square values of the former range from 0.5 cm to 2 cm, while the latter ranges from 10 1 cm to 6 cm, for a typical 84 hr forecast. The spatial and temporal variability of the forecast error is related to the dynamical origins of the non-phase-locked tide and is briefly surveyed within the model. -

Anidación De La Tortuga Carey (Eretmochelys Imbricata) En Isla De Mona, Puerto Rico

Anidación de la tortuga carey (Eretmochelys imbricata) en Isla de Mona, Puerto Rico. Carlos E. Diez 1, Robert P. van Dam 2 1 DRNA-PR PO Box 9066600 Puerta de Tierra San Juan, PR 00906 [email protected] 2 Chelonia Inc PO Box 9020708 San Juan, PR 00902 [email protected] Palabras claves: Reptilia, carey de concha, Eretmochelys imbricata, anidación, tortugas marinas, marcaje, conservación, Caribe, Isla de Mona, Puerto Rico. Resumen El carey de concha, Eretmochelys imbricata, es la especie de tortuga marina más abundante en nuestras playas y costas. Sin embargo está clasificada como una especie en peligro de extinción por leyes estatales y federales además de estar protegida a nivel internacional. Uno de los lugares más importantes del Caribe para la reproducción de esta especie es en la Isla de Mona, Puerto Rico. Los resultados del monitoreo de la actividad de anidaje en la Isla de Mona han demostrado un incremento siginificativo en el números de nidos de la tortuga carey depositado en la isla durante los últimos años. En el año 2005 se contó un total de 1003 nidos de carey depositados en todas las playas de Isla de Mona durante 116 días de monitoreo, lo cual es una cantidad mayor que durante cualquier censo en años anteriores (en 1994 se contaron 308 nidos depositados en 114 días). De igual manera, el Índice de Actividades de Anidaje cual esta basado en conteos precisos durante 60 dias aumento a partir de su estableciemiento en el 2003 con 298 nidos de carey con 18% a 353 nidos en 2004 y resultando en 368 nidos en el 2005. -

Reconnaissance Investigation of Caribbean Extreme Wave Deposits – Preliminary Observations, Interpretations, and Research Directions

RECONNAISSANCE INVESTIGATION OF CARIBBEAN EXTREME WAVE DEPOSITS – PRELIMINARY OBSERVATIONS, INTERPRETATIONS, AND RESEARCH DIRECTIONS Robert A. Morton, Bruce M. Richmond, Bruce E. Jaffe, and Guy Gelfenbaum Open-File Report 2006-1293 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover photograph – Panorama view on the north coast of Bonaire at Boka Kokolishi in March 2006 showing (from left to right), Caribbean Sea, modern sea cliff, scattered boulders and sand deposits on an elevated rock platform, and a paleo-seacliff. Wave swept zone and fresh sand deposits were products of Hurricane Ivan in September 2004. RECONNAISSANCE INVESTIGATION OF CARIBBEAN EXTREME WAVE DEPOSITS – PRELIMINARY OBSERVATIONS, INTERPRETATIONS, AND RESEARCH DIRECTIONS 1 2 2 3 Robert A. Morton , Bruce M. Richmond , Bruce E. Jaffe , and Guy Gelfenbaum 1U.S. Geological Survey, 600 Fourth St. S., St. Petersburg, FL 33701 2U.S. Geological Survey, 400 Natural Bridges Drive, Santa Cruz, CA 95060 USA 3U.S. Geological Survey, 345 Middlefield Rd., Menlo Park, CA 94025 USA Open-File Report 2006-1293 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey i Contents SUMMARY ...........................................................................................................................................................................1 INTRODUCTION...................................................................................................................................................................1 GENERAL GEOLOGIC SETTING .........................................................................................................................................1 -

Oblique Collision in the Northeastern Caribbean from GPS Measurements and Geological Observations

TECTONICS, VOL. 21, NO. 6, 1057, doi:10.1029/2001TC001304, 2002 Oblique collision in the northeastern Caribbean from GPS measurements and geological observations Paul Mann,1 Eric Calais,2 Jean-Claude Ruegg,3 Charles DeMets,4 Pamela E. Jansma,5 and Glen S. Mattioli6 Received 31 May 2001; revised 16 April 2002; accepted 10 June 2002; published 11 December 2002. [1] Previous Caribbean GPS studies have shown that Tectonophysics: Continental neotectonics; 8105 Tectonophysics: the rigid interior of the Caribbean plate is moving east- Continental margins and sedimentary basins; 3025 Marine Geology northeastward (070°) at a rate of 18–20 ± 3 mm/yr and Geophysics: Marine seismics (0935); 3040 Marine Geology relative to North America. This direction implies and Geophysics: Plate tectonics (8150, 8155, 8157, 8158); 7230 maximum oblique convergence between the island of Seismology: Seismicity and seismotectonics; KEYWORDS: GPS, neotectonics, Hispaniola, Puerto Rico, Bahama Platform, Hispaniola on the Caribbean plate and the 22–27-km- earthquakes. Citation: Mann, P., E. Calais, J.-C. Ruegg, C. thick crust of the Bahama carbonate platform on the DeMets, P. E. Jansma, and G. S. Mattioli, Oblique collision in the adjacent North America plate. We present a tectonic northeastern Caribbean from GPS measurements and geological interpretation of a 15-site GPS network which spans observations, Tectonics, 21(6), 1057, doi:10.1029/2001TC001304, the Hispaniola-Bahama oblique collision zone and 2002. includes stable plate interior sites on both the North America and Caribbean plates. Measurements span the time period of 1994–1999. In a North America 1. Introduction reference frame, GPS velocities in Puerto Rico, St. -

Guide to Theecological Systemsof Puerto Rico

United States Department of Agriculture Guide to the Forest Service Ecological Systems International Institute of Tropical Forestry of Puerto Rico General Technical Report IITF-GTR-35 June 2009 Gary L. Miller and Ariel E. Lugo The Forest Service of the U.S. Department of Agriculture is dedicated to the principle of multiple use management of the Nation’s forest resources for sustained yields of wood, water, forage, wildlife, and recreation. Through forestry research, cooperation with the States and private forest owners, and management of the National Forests and national grasslands, it strives—as directed by Congress—to provide increasingly greater service to a growing Nation. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD).To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, S.W. Washington, DC 20250-9410 or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Authors Gary L. Miller is a professor, University of North Carolina, Environmental Studies, One University Heights, Asheville, NC 28804-3299. -

Rhesus Macaque Eradication to Restore the Ecological Integrity of Desecheo National Wildlife Refuge, Puerto Rico

C.C. Hanson, T.J. Hall, A.J. DeNicola, S. Silander, B.S. Keitt and K.J. Campbell Hanson, C.C.; T.J. Hall, A.J. DeNicola, S. Silander, B.S. Keitt and K.J. Campbell. Rhesus macaque eradication to restore the ecological integrity of Desecheo National Wildlife Refuge, Puerto Rico Rhesus macaque eradication to restore the ecological integrity of Desecheo National Wildlife Refuge, Puerto Rico C.C. Hanson¹, T.J. Hall¹, A.J. DeNicola², S. Silander³, B.S. Keitt¹ and K.J. Campbell1,4 ¹Island Conservation, 2100 Delaware Ave. Suite 1, Santa Cruz, California, 95060, USA. <chad.hanson@ islandconservation.org>. ²White Buff alo Inc., Connecticut, USA. ³U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Caribbean Islands› NWR, P.O. Box 510 Boquerón, 00622, Puerto Rico. 4School of Geography, Planning & Environmental Management, The University of Queensland, St Lucia 4072, Australia. Abstract A non-native introduced population of rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) was targeted for removal from Desecheo Island (117 ha), Puerto Rico. Macaques were introduced in 1966 and contributed to several plant and animal extirpations. Since their release, three eradication campaigns were unsuccessful at removing the population; a fourth campaign that addressed potential causes for previous failures was declared successful in 2017. Key attributes that led to the success of this campaign included a robust partnership, adequate funding, and skilled fi eld staff with a strong eradication ethic that followed a plan based on eradication theory. Furthermore, the incorporation of modern technology including strategic use of remote camera traps, monitoring of radio-collared Judas animals, night hunting with night vision and thermal rifl e scopes, and the use of high-power semi-automatic fi rearms made eradication feasible due to an increase in the probability of detection and likelihood of removal.