Perverted by Language: Weird Fiction and the Semiotic Anomalies of a Genre

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Children Entering Fourth Grade ~

New Canaan Public Schools New Canaan, Connecticut ~ Summer Reading 2018 ~ Children Entering Fourth Grade ~ 2018 Newbery Medal Winner: Hello Universe By Erin Entrada Kelly Websites for more ideas: http://booksforkidsblog.blogspot.com (A retired librarian’s excellent children’s book blog) https://www.literacyworldwide.org/docs/default-source/reading-lists/childrens- choices/childrens-choices-reading-list-2018.pdf Children’s Choice Awards https://www.bankstreet.edu/center-childrens-literature/childrens-book-committee/best- books-year/2018-edition/ Bank Street College Book Recommendations (All suggested titles are for reading aloud and/or reading independently.) Revised by Joanne Shulman, Language Arts Coordinator joanne,[email protected] New and Noteworthy (Reviews quoted from amazon.com) Word of Mouse by James Patterson “…a long tradition of clever mice who accomplish great things.” Fish in a Tree by Lynda Mallaly Hunt “Fans of R.J. Palacio’s Wonder will appreciate this feel-good story of friendship and unconventional smarts.”—Kirkus Reviews Secret Sisters of the Salty Seas by Lynne Rae Perkins “Perkins’ charming black-and-white illustrations are matched by gentle, evocative language that sparkles like summer sunlight on the sea…The novel’s themes of family, friendship, growing up and trying new things are a perfect fit for Perkins’ middle grade audience.”—Book Page Dash (Dogs of World War II) by Kirby Larson “Historical fiction at its best.”—School Library Journal The Penderwicks at Last by Jean Birdsall “The finale you’ve all been -

Teaching Speculative Fiction in College: a Pedagogy for Making English Studies Relevant

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Dissertations Department of English Summer 8-7-2012 Teaching Speculative Fiction in College: A Pedagogy for Making English Studies Relevant James H. Shimkus Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss Recommended Citation Shimkus, James H., "Teaching Speculative Fiction in College: A Pedagogy for Making English Studies Relevant." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2012. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss/95 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TEACHING SPECULATIVE FICTION IN COLLEGE: A PEDAGOGY FOR MAKING ENGLISH STUDIES RELEVANT by JAMES HAMMOND SHIMKUS Under the Direction of Dr. Elizabeth Burmester ABSTRACT Speculative fiction (science fiction, fantasy, and horror) has steadily gained popularity both in culture and as a subject for study in college. While many helpful resources on teaching a particular genre or teaching particular texts within a genre exist, college teachers who have not previously taught science fiction, fantasy, or horror will benefit from a broader pedagogical overview of speculative fiction, and that is what this resource provides. Teachers who have previously taught speculative fiction may also benefit from the selection of alternative texts presented here. This resource includes an argument for the consideration of more speculative fiction in college English classes, whether in composition, literature, or creative writing, as well as overviews of the main theoretical discussions and definitions of each genre. -

Rosemary Ellen Guiley

vamps_fm[fof]_final pass 2/2/09 10:06 AM Page i The Encyclopedia of VAMPIRES, WEREWOLVES, and OTHER MONSTERS vamps_fm[fof]_final pass 2/2/09 10:06 AM Page ii The Encyclopedia of VAMPIRES, WEREWOLVES, and OTHER MONSTERS Rosemary Ellen Guiley FOREWORD BY Jeanne Keyes Youngson, President and Founder of the Vampire Empire The Encyclopedia of Vampires, Werewolves, and Other Monsters Copyright © 2005 by Visionary Living, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher. For information contact: Facts On File, Inc. 132 West 31st Street New York NY 10001 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Guiley, Rosemary. The encyclopedia of vampires, werewolves, and other monsters / Rosemary Ellen Guiley. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8160-4684-0 (hardcover : alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-4381-3001-9 (e-book) 1. Vampires—Encyclopedias. 2. Werewolves—Encyclopedias. 3. Monsters—Encyclopedias. I. Title. BF1556.G86 2004 133.4’23—dc22 2003026592 Facts On File books are available at special discounts when purchased in bulk quantities for businesses, associations, institutions, or sales promotions. Please call our Special Sales Department in New York at (212) 967-8800 or (800) 322-8755. You can find Facts On File on the World Wide Web at http://www.factsonfile.com Printed in the United States of America VB FOF 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 This book is printed on acid-free paper. -

Archives Fine Books Catalogue 12

ARCHIVES FINE BOOKS CATALOGUE 12 2020 rom early March 2020, Catalogue 12 was never a certainty. We held our breath and watched as events were cancelled and postponed, including the ANZAAB Antiquarian and Rare Book Fairs. But in the slowing and stilling of those weeks and months something lovely happened: Archives FFine People called and ordered books or bought them through our website, and many booked appointments for quiet, socially distant browsing. Dedicated book collectors kept collecting books and others discovered they loved books too. We didn’t acquire much stock in this period, but when we were offered a small collection of mid-to-late twentieth century illustrated and signed items we were feeling cheery and hopeful, took them on, and Catalogue 12 came into being. Between the covers you will find John and Yoko, Ray Bradbury, Three Dog Night, Harvey Kurtzman, Jenny Saville and more. True to form we have tucked a little William Blake in the mix on pp. 6 & 17. We hope you enjoy browsing and if we can reserve something special for you please let us know. Dawn & Hamish. Front Cover: Ono, Yoko. Grapefruit. New York: ARCHIVES FINE BOOKS PTY LTD Sphere, 1971. First Thus. SIGNED BY YOKO ONO AND JOHN LENNON. (# 1263). Details p. 4. 40 CHARLOTTE STREET, BRISBANE, QUEENSLAND, 4000 ‡ +61 7 3221 0491 Back Cover: Detail from SAVILLE, Jenny. Jenny Saville. New York: Rizzoli International Publications, [email protected] Inc., 2005. First Edition. SIGNED. Details p. 15. www.archivesfinebooks.com.au 2 The John Lennon Letters; Edited and with an Introduction by Hunter Davies. -

Toward a Theory of the Dark Fantastic: the Role of Racial Difference in Young Adult Speculative Fiction and Media

Journal of Language and Literacy Education Vol. 14 Issue 1—Spring 2018 Toward a Theory of the Dark Fantastic: The Role of Racial Difference in Young Adult Speculative Fiction and Media Ebony Elizabeth Thomas Abstract: Humans read and listen to stories not only to be informed but also as a way to enter worlds that are not like our own. Stories provide mirrors, windows, and doors into other existences, both real and imagined. A sense of the infinite possibilities inherent in fairy tales, fantasy, science fiction, comics, and graphic novels draws children, teens, and adults from all backgrounds to speculative fiction – also known as the fantastic. However, when people of color seek passageways into &the fantastic, we often discover that the doors are barred. Even the very act of dreaming of worlds-that-never-were can be challenging when the known world does not provide many liberatory spaces. The dark fantastic cycle posits that the presence of Black characters in mainstream speculative fiction creates a dilemma. The way that this dilemma is most often resolved is by enacting violence against the character, who then haunts the narrative. This is what readers of the fantastic expect, for it mirrors the spectacle of symbolic violence against the Dark Other in our own world. Moving through spectacle, hesitation, violence, and haunting, the dark fantastic cycle is only interrupted through emancipation – transforming objectified Dark Others into agentive Dark Ones. Yet the success of new narratives fromBlack Panther in the Marvel Cinematic universe, the recent Hugo Awards won by N.K. Jemisin and Nnedi Okorafor, and the blossoming of Afrofuturistic and Black fantastic tales prove that all people need new mythologies – new “stories about stories.” In addition to amplifying diverse fantasy, liberating the rest of the fantastic from its fear and loathing of darkness and Dark Others is essential. -

Dark Romanticism Notes (1840-1865)

Dark Romanticism Notes (1840-1865) Authors Associated with Dark Romanticism (172) Characteristics of Dark Romanticism Philosophy (173) Beliefs of the Dark Romantics: B elieve that perfection was not ingrained in humanity. Some Mr. Randon Notes (PPT) Believe that individuals were prone to sin and self-destruction, not as inherently possessing divinity and wisdom. Edgar Allan Poe “Factoids” (Documentary) Frequently shows individuals failing in their attempts to make changes for the better. Romantics and Dark Romantics both believe that nature is a deeply spiritual force, however, Dark Romanticism views nature as sinister and evil. When nature does reveal truth to man, its revelations are pessemistic and soul-crushing. 1 An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge Film Guide Think about the director’s decisions as he adapts Ambrose Bierce’s short story to film. Analysis: What does it mean for the Detail How is the detail distorted? character? Sound 2 Berenice (Abridged) By Edgar Allen Poe (1835) Dicebant mihi sodales, si sepulchrum amicae visitarem, curas meas aliquantulum forelevatas. - Ebn Zaiat MISERY is manifold. The wretchedness of earth is multiform. Overreaching the wide horizon as the rainbow, its hues are as various as the hues of that arch - as distinct too, yet as intimately blended. Overreaching the wide horizon as the rainbow! How is it that from beauty I have derived a type of unloveliness? - from the covenant of peace, a simile of sorrow? But as, in ethics, evil is a consequence of good, so, in fact, out of joy is sorrow born. Either the memory of past bliss is the anguish of to-day, or the agonies which are, have their origin in the ecstasies which might have been. -

Fantastic Beasts in the Museum

MyGuide A Classic Court (Gallery 2) Ancient Egyptian, Funerary Book of Tamesia, about 100 CE The ancient Egyptian demoness/goddess Ammit is a fearsome composite of a crocodile, lion, and hippo. Called “The Devourer,” she played a role in the Weighing of the Heart, when a person who has died comes before 42 divine judges to plead their case for passing into the Afterlife. If their heart turns out to be heavier than a feather, it is tossed to Ammit, who devours it, dooming the deceased’s soul to wander forever. B Classic Court (Gallery 2) Fantastic Ancient Greek, Griffin Protome from a Cauldron, about 600 BCE The legendary griffin—part eagle, snake, hare, Draco dormiens and lion—may have originated in ancient Iran or Beasts even ancient Egypt, but was found in cultures nunquam titillandus across Central Asia and Turkey. In ancient Greece, Mythological animals, cryptozoological griffins were protective figures and were considered (Never tickle a sleeping dragon). creatures, monsters—whatever you guardians of treasure. call them, pretty much every culture across history has them. This guide Gallery 3 C will show you where to find some Joan Miró, Woman Haunted by the fantastic beasts in the Museum. Passage of the Bird-Dragonfly Omen of Bad News, 1938 Sometimes, monsters are of our own making. Concerned that war may be on the horizon (World War II would start the following year), Joan Miró created three fantastical creatures that together seem to embody a portent of disruption and doom beyond the control of humankind. D Gallery 10 Wahei Workshop, Netsuke: Tanuki, late 19th century The most adorable creature on this tour, the tanuki, or racoon-dog, is a real animal native to Japan. -

That of Cultural Representations of the Magic Circle in Its Occult Usage

11. Six Lecti.o on Occult Philosophy 3. tlodgson's Corttflckt ttte Ghost-FiiideT ~ ``rThe BOTdetlaLnds" (Owter Li77iits) Up to this point we've been considering variations on a theme: that of cultural representations of the magic circle in its occult usage. In these stories the rmagic circle rmaintalns a basic function, which is to govern the boundary between the natural and the supematural, be it in terms of acting as a protective barrier, or in terms of evoking the supernatural from the safety inside the circle. We can now take another step, which is to consider instances in which the anomalies that occur are not inside or outside the magic circle, but are anomalies o/the magic circle itself . This need not mean that the magic circle malfunc- tions, or has been improperly drawn. In some cases it may mean that the magic circle - as the boundary and mediation of the hidden world - itself reveals some new property or propensity. A case in point is in the ``occult detective" subgenre, a style of fiction popular in the 19th century. In these types of stories, a hero-protagonist combines knowledge of modern science with that of ancient magic to solve a series of crimes and mysteries that may or may not have supernatural causes. Algernon B\aLckwood's John Silence - Physician Extraordinary iind SiheridaLr\ Le Fanu's J# ¢ GJ¢ss D¢rkzy are examples in fiction, while Charles Fort's Tfee Book o/ ffec D¢77i77ed is an example in non-fiction. These types of stories are not only the precursors to modern-day TV shows such as X-/1.Zes or f7i.7tge, but they also bring together science and sorcery into a new relationship. -

Universidade Federal De Santa Catarina Pós

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE SANTA CATARINA PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM LETRAS/INGLÊS E LITERATURA CORRESPONDENTE WEIRD FICTION AND THE UNHOLY GLEE OF H. P. LOVECRAFT KÉZIA L’ENGLE DE FIGUEIREDO HEYE Dissertação Submetida à Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina em cumprimento dos requisitos para obtenção do grau de MESTRE EM LETRAS Florianópolis Fevereiro, 2003 My heart gave a sudden leap of unholy glee, and pounded against my ribs with demoniacal force as if to free itself from the confining walls of my frail frame. H. P. Lovecraft Acknowledgments: The elaboration of this thesis would not have been possible without the support and collaboration of my supervisor, Dra. Anelise Reich Courseil and the patience of my family and friends, who stood by me in the process of writing and revising the text. I am grateful to CAPES for the scholarship received. ABSTRACT WEIRD FICTION AND THE UNHOLY GLEE OF H. P. LOVECRAFT KÉZIA L’ENGLE DE FIGUEIREDO HEYE UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE SANTA CATARINA 2003 Supervisor: Dra. Anelise Reich Corseuil The objective of this thesis is to verify if the concept of weird fiction can be classified not only as a sub-genre of the horror literary genre, but if it constitutes a genre of its own. Along this study, I briefly present the theoretical background on genre theory, the horror genre, weird fiction, and a review of criticism on Lovecraft’s works. I also expose Lovecraft’s letters and ideas, expecting to show the working behind his aesthetic theory on weird fiction. The theoretical framework used in this thesis reflects some of the most relevant theories on genre study. -

Henry Kuttner, a Memorial Symposium

EDITED BY K /\ R E N A N 0 E R S 0 M A S E V A G R A M ENTERPRISE Tomorrow and. tomorrow "bring no more Beggars in velvet, Blind, mice, pipers'- sons; The fairy chessmen will take wing no more In shock and. clash by night where fury runs, A gnome there was, whose paper ghost must know That home there’s no returning -- that the line To his tomorrow went with last year’s snow, Gallegher Plus no longer will design Robots who have no tails; the private eye That stirred two-handed engines, no more sees. No vintage seasons more, or rich or wry, That tantalize us even to the lees; Their mutant branch now the dark angel shakes Arid happy endings end when the bough breaks. Karen Anderson 2. /\ MEMORIAL symposium. ■ In Memoriams Henry Kuttnei; (verse) Karen Anderson 2 Introduction by the Editor 4 Memoirs of a Kuttner Reader Poul Anderson 4 The Many Faces of Henry Kuttner Fritz Leiher 7 ’•Hank Helped Me” Richard Matheson 10 Ray Bradbury 11 The Mys^&r.y Hovels of Henry Kuttner Anthony. Boucher . .; 12 T^e Closest Approach • Robert Bloch . 14 Extrapolation (fiction) Henry Kuttner Illustrated by John Grossman ... (Reprinted from The Fanscient, Fall 1948) 19 Bibliography of the Science-Fantasy Works of Henry.. Kuttner Compiled by Donald H..Tuck 23 Kotes on Bylines .. Henry Kuttner ... (Reproduced from a letter) 33 The verse on Page 2 is reprinted from the May, 1958 issue of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science-Fiction, Illustrations by Edd Cartier on pages 9, 18, and 23 are reproduced respectively from Astounding Science Fiction. -

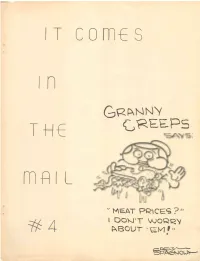

It Comes in the Mail 4

CREEPS " MEAT PP1CE<S ?' I OOKJ’T ^OQRV fXBOUT "£M f - PAKTOVM Oi? THE PMSBED PUBS by Don Marquis Where has my little dog gone? Grief 5.3 'wrecking ray reason.- (fie vanished in the Daw.) This is the Sausage Season. Grief is wrecking ray reason. (I. doubt theej Butcher Man.) This is the Sausage Season. (Meat -'®e Hing Caliban i) I doubt thee, Butcher Man - His collar with gold was erusted, Meet-selling Caliban! he had a heart that trusted. His collar with gold was crusted - (0 Butcher, whet and mile!) Re had a heart that trusted? Thy heart is full of guile! 0 Butcher, whet and anile, My doubt of thee profound is? Thy heart is full of guile - And sausage two shillings a pound is! My doubt of thee profound is: He oft paused by thy door! And sausage two shillings a pound is! Ke lingered near thy store! He oft cause by thy door - 0 Butcher enterprising! He lingered near thy store - The price of sausage is rising! 0 Butcher enterprising, Where has my little dog gone? The price of sausage is rising; - He vanished in the Dawn! - from Noah An’ Jonah An^ Cap*a John Smith (thanks to Bruce Arthurs!) IT COMES IN THE MAIL - Number Four Ned Brooks, 713 Paul Street, Newport News, Virginia - 23605, for SFPA 53 & others Cover art by Greg Spagnola, courtesy George Beahm < OOOOOCOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOCOO . Ji y In running off the previous issue, I discovered that the third page stencil had been typed far too long, and would not fit on the page at all, so that to run it at all I had to corflu out the last three lines. -

Cosmic Horror’ in American Culture

From Poe to South Park: The Influence and Development of Lovecraft’s ‘Cosmic Horror’ in American Culture Christian Perwein University of Graz [email protected] ABSTRACT H.P. Lovecraft’s ‘Cosmic Horror’ has been a staple of horror and gothic fiction, and therefore American culture, for more than 80 years. In this paper, I examine the development of the genre of horror, starting with Edgar Allen Poe’s influence, and trace its development up to contemporary popular American culture exemplified by the TV show South Park. While Lovecraft’s material has always been drawing from the same concept of the fear of the unknown and human powerlessness in the face of greater forces, the context, sources and reasons for this powerlessness have constantly changed over the decades. In this paper I offer an examination of where this idea of ‘Cosmic Horror’ originally came from, how Lovecraft developed it further and, ultimately, how American culture has adapted the source material to fit a contemporary context. By contrasting Lovecraft’s early works with Poe’s, I shed light on the beginnings of the sub-genre before taking a look at the height of ‘Cosmic Horror’ in Lovecraft’s most famous texts of the Cthulhu myth and ultimately look at a trilogy of South Park episodes to put all of this into a modern American perspective. By doing so, I reveal how Lovecraft’s tales and the underlying philosophy have always been an important part of American culture and how they continue to be relevant even today. KEYWORDS cosmic horror, gothic, Lovecraft Perwein, Christian.