Journal of the Royal Musical Association; 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Benny Sings - City Pop 22 February 2019

Benny Sings - City Pop 22 February 2019 “For more than 10 years, fans have been drawn to Dutch singer-songwriter Benny Sings' ability to layer R&B, jazz and pop over hip-hop foundations.” — NPR Music Benny Sings will release City Pop, his sixth album and first for Stones Throw in February 2019. With his signing to Stones Throw, he joins the label’s roster of artists — such as Jerry Paper and Mild High Club — in making music at the intersection of jazz, AOR, R&B and soul. On City Pop, he delivers real-life observations and insights on love, holding together soft rock-inspired songwriting and jazz instrumentation with his leading piano and distinctive vocal. The album was inspired by and written in cities all over the world, including New York, LA, Tokyo, Paris and Benny’s hometown of Amsterdam. Benny Sings debuted in 2003 with Champagne People. Since then he has performed for NPR’s Tiny Desk (their only Dutch guest to date); toured the world with Mayer Hawthorne, and collaborated with the likes of Anderson .Paak, GoldLink, and Mndsgn. In 2017 he co-wrote and featured on Rex Orange County’s megahit “Loving Is Easy”, a collaboration that arose from mutual admiration: "Benny has always been a massive inspiration for me and my music,” says the BBC Sound of 2018 breakout star, “In my opinion he’s one of the most underrated producers and artists going.” Like the 2015 album Studio, City Pop celebrates collaboration, with Hawthorne, Cornelius, Sukima switch (the “Japanese Steely Dan”), Mocky and Faberyayo among the featured artists. -

Suite Sounds

Suite Sounds Glasgow-based DJ, producer and jazz guru, Rebecca Vasmant is the brains behind Era Suite, a new party night at Sub Club bringing jazz, Afrobeat, Latin, funk and electronica to the dance floor Interview: Claire Francis ebecca Vasmant has long been known in come and play in a club/dancefloor environment, RGlasgow’s club scene for her fusing of jazz hopefully bringing people from both the jazz influences and modern electronic sounds. She scene and the electronic scene together. cemented her place in the city’s scene with her Made In Glasgow and Know The Way parties, and Can you tell us about Sub Club’s history as a her regular spot on BBC Radio Scotland’s The Jazz jazz venue and how this fits in with the Era House saw her present some of the best contem- Suite nights? porary jazz to a wide audience. Now, she’s taking Sub Club has an amazing history with jazz. Before the genre in all of its iterations to the Sub Club in Sub Club was booking the likes of Bonobo and new night Era Suite, combining selections from Gilles Peterson, it was previously called Lucifers. her collection with live slots from jazz musi- Before that, the club operated as the Jamaica cians and bands. We caught up with Vasmant to Inn, serving chicken in a basket to patrons – a talk about her love of the genre, the genesis of cheeky little way to allow it to stay open longer the new night and her highlights from the past 12 than other bars! But back in the 1950s and 60s, months. -

White+Paper+Music+10.Pdf

In partnership with COPYRIGHT INFORMATION This white paper is written for you. Wherever you live, whatever you do, music is a tool to create connections, develop relationships and make the world a little bit smaller. We hope you use this as a tool to recognise the value in bringing music and tourism together. Copyright: © 2018, Sound Diplomacy and ProColombia Music is the New Gastronomy: White Paper on Music and Tourism – Your Guide to Connecting Music and Tourism, and Making the Most Out of It Printed in Colombia. Published by ProColombia. First printing: November 2018 All rights reserved. No reproduction or copying of this work is permitted without written consent of the authors. With the kind support of the World Tourism Organization (UNWTO). The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of the UNWTO or its members. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinions whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the World Tourism Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Address Sound Diplomacy Mindspace Aldgate, 114 Whitechapel High St, London E1 7PT Address ProColombia Calle 28 # 13a - 15, piso 35 - 36 Bogotá, Colombia 2 In partnership with CONTENT MESSAGE SECRETARY-GENERAL, UNWTO FOREWORD EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. INTRODUCING MUSIC TOURISM 1.1. Why Music? 1.2. Music as a Means of Communication 1.3. Introducing the Music and Tourism Industries 1.3.1. -

Sibusile Epk001

Part acoustic guitar visionary, part urban mythologist, Sibusile Xaba’s improvisational style hints at maskandi, while also shrinking the middle passage to connect jazz to its precolonial antecedents. KwaZulu-Natal-born guitarist and vocalist Sibusile Xaba has all the makings of an acoustic guitar master. With a vocal style that is part dreamscaping and part ancestral invocation, Xaba divines as opposed to plainly singing. Combined with a guitar style that is rooted in expressive picking, Xaba's music shatters the confines of genre, taking only the fundamentals from mentors such as Madala Kunene and Dr Philip Tabane and imbuing these with a mythology and improvisational intensity all of his own. His debut double album – ‘Unlearning’ & ‘Open Letter to Adoniah’ - was released internationally on 4 August 2017 to critical acclaim (see links to reviews below). 2017 saw Sibusile touring through various countries in Africa and Europe, where he performed at a number of prestigious music festivals (e.g. Shambala and Jazz ala Villette), music venues (e.g. Ronnie Scotts) and radio stations (e.g. Worldwide FM & Radio France). Sibusile will be touring extensively during the course of 2018 promoting his debut release. OPEN LETTER TO ADONIAH 'Open Letter to Adoniah' is an album reverent of life and its connectedness to a higher source. The music emanates from dreams revealed to Xaba over consecutive days and most of the album was recorded live in the mountains of Magaliesberg outside Johannes- burg in the winter of 2016. With percussionists Thabang Tabane and Dennis Moanganei Magagula, the trio coalesces both geographic and spiritual influences, hinting at Maskandi (a music style dominant in Xaba’s native KwaZulu-Natal) and the improvisational culture of South Africa's jazz avant garde. -

October 2011

SEPTEMBE R - OCTOBER 2011 Featuring: Wynton Marsalis | Family Stone | Remembering Oscar Peterson | Incognito | John Williams/Etheridge | Pee Wee Ellis | JTQ | Colin Towns Mask Orch | Azymuth | Todd Rundgren | Cedar Walton | Carleen Anderson | Louis Hayes and The Cannonball Legacy Band | Julian Joseph All Star Big Band | Mike Stern feat. Dave Weckl | Ramsey Lewis | James Langton Cover artist: Ramsey Lewis Quintet (Thur 27 - Sat 29 Oct) PAGE 28 PAGE 01 Membership to Ronnie Scotts GIGS AT A GLANCE SEPTEMBER THU 1 - SAT 3: JAMES HUNTER SUN 4: THE RONNIE SCOTT’S JAZZ ORCHESTRA PRESENTS THE GENTLEMEN OF SWING MON 5 - TUE 6: THE FAMILY STONE WED 7 - THU 8: REMEMBERING OSCAR PETERSON FEAT. JAMES PEARSON & DAVE NEWTON FRI 9 - SAT 10: INCOGNITO SUN 11: NATALIE WILLIAMS SOUL FAMILY MON 12 - TUE 13: JOHN WILLIAMS & JOHN ETHERIDGE WED 14: JACQUI DANKWORTH BAND THU 15 - SAT 17: PEE WEE ELLIS - FROM JAZZ TO FUNK AND BACK SUN 18: THE RONNIE SCOTT’S BLUES EXPLOSION MON 19: OSCAR BROWN JR. TRIBUTE FEATURING CAROL GRIMES | 2 free tickets to a standard price show per year* TUE 20 - SAT 24: JAMES TAYLOR QUARTET SUN 25: A SALUTE TO THE BIG BANDS | 20% off all tickets (including your guests!)** WITH THE RAF SQUADRONAIRES | Dedicated members only priority booking line. MON 26 - TUE 27: ROBERTA GAMBARINI | Jump the queue! Be given entrance to the club before Non CELEBRATING MILES DAVIS 20 YEARS ON Members (on production of your membership card) WED 28 - THU 29: ALL STARS PLAY ‘KIND OF BLUE’ FRI 30 - SAT 1 : COLIN TOWNS’ MASK ORCHESTRA PERFORMING ‘VISIONS OF MILES’ | Regular invites to drinks tastings and other special events in the jazz calendar OCTOBER | Priority information, advanced notice on acts appearing SUN 2: RSJO PRESENTS.. -

March 10, 2021 Jordan Rakei Announces Late Night Tales Compilation, out April

March 10, 2021 For Immediate Release Jordan Rakei Announces Late Night Tales Compilation, Out April 9th Listen to Rakei’s Exclusive Cover of Jeff Buckley’s “Lover, You Should've Come Over” (Photo Credit: Dan Medhurst) The artist-curated mix series, Late Night Tales, is pleased to announce its next compilation, this time curated by multi-instrumentalist, vocalist and producer Jordan Rakei, out April 9th. For Rakei’s Late Night Tales, the first mix of the acclaimed series’ 20th year, the 28-year-old modern soul icon effortlessly stamps his own jazz and hip-hop driven sound all over this gorgeous array of handpicked tracks. A beautifully layered blend that is mirrored in the music he’s made, it comes as no surprise that such a supremely gifted songwriter should deliver a mix that is all about the song. “I wanted to try and showcase as many people as I knew on this mix,” says Rakei. “My idea of Late Night Tales was to distil a series of relaxing moments; the whole conceptual sonic of relaxation. So, I was trying to think of all the collaborators and friends that I knew, who’d recorded stuff with this horizontal vibe. Plus, I was also trying to help my friends' stuff get into the world. I know the story of Khruangbin blowing up after appearing on the series (in fact, I think that's how I discovered them). So, the main idea was to create a certain atmosphere, but also to help some of my favourite collaborators and buddies to give their songs a little push out into the world. -

THE ASU CONCERT Jall BAND with VOCALIST MARK MURPHY

THE ASU CONCERT JAll BAND WITH VOCALIST MARK MURPHY MICHAEL KOCOUR, DIRECTOR DON OWENS, GUEST DIRECTOR GUEST ARTIST CONCERT SERIES EVELYN SMITH MUSIC THEATRE MARCH 26-27 • 7:30 PM MU S IC -°HerbergerCollege of the Arts ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY Program "Tonight Show" with Steve Allen. It was Allen's composition, "This Could Be the Start of Something Big," that Mark recorded a hit rendition of in 1959. Murphy's recording career began at the age of 24 with his first release, Meet Mark To be announced. Murphy, on the Decca label. Producer Orrin Keepnews recalls Murphy's early recordings as "timeless...it's remarkable how fully developed as an artist Mark was so early on. He Alto Saxophone Trombone was born with his incredible rhythmic sense. And he's matured throughout the years, his Keith Kelly Mike Wilkinson vocal powers remain undiminished." In 1958 Murphy moved to Los Angeles and recorded three albums for Capitol Records. Javier Ocampo Seth Gory He returned to New York in the early '60s and did the now classic jazz recording Rah Jeff Hattasch on the Riverside label, featuring legendary jazz players Bill Evans, Clark Terry, Urbie Tenor Saxophone Pat Lawrence Jeff Gutierrez Green, Blue Mitchell and Wynton Kelly. This album has been recently reissued by Fantasy Gabriel Sears Records. Mark's favorite recording to date, That's How I Love the Blues, soon followed. In Woody Chenoweth 1963 Murphy hit the charts across the country with his single of "Fly Me To the Moon" Tuba Baritone Saxophone and was voted "New Star of the Year" in Downbeat Magazine's Reader's Poll. -

Roberto Fonseca and the Havana Cultura Band

GILLES PETERSON PRESENTS HAVANA CULTURA: REMIXED CD02 / BONUS DJ MIX BY GILLES PETERSON CD01 / THE REMIXES 01. THINK TWICE / 4HERO REMIX FEAT. DANAY & CARINA 01. MAMI / EDGARO EL PRODUCTOR EN JEFE TROPICALIA REMIX 02. MAMI / EDGARO EL PRODUCTOR EN JEFE TROPICALIA REMIX 02. ROFOROFO FIGHT / LOUIE VEGA’S EOL MIX 03. AFRODISIA / RAINER TRUEBY REMIX 03. REZANDO / MICHEL CLEIS REMIX 04. ROFOROFO FIGHT / LOUIE VEGA’S EOL MIX 04. CHEKERE SON / SEIJI RERUB 05. ROFOROFO FIGHT / LOUIE VEGA REMIX 05. ARROZ CON POLLO / MJ COLE REMIX 06. LAGRIMAS DE SOLEDAD (NO EXISTEN PALABRAS) / D’WALA RIDDIMIX 06. ARROZ CON POLLO / CARL COX MIX 07. CHEKERE SON / ALEX PATCHWORK REMIX 07. LA REVOLUCION DEL CUERPO PT.1 / SKINNER’S OWINEY SIGOMA MIX 08. LA REVOLUCION DEL CUERPO PT.1 / SKINNER’S OWINEY SIGOMA MIX 08. AFRODISIA / RAINER TRUEBY REMIX 09. REZANDO / MICHEL CLEIS REMIX 09. THINK TWICE / 4HERO REMIX FEAT. DANAY & CARINA 10. CHEKERE SON / SEIJI RERUB 10. ARROZ CON POLLO / SOLAL “SOY CUBA” REMIX 11. ARROZ CON POLLO / MJ COLE REMIX 11. CHEKERE SON / WICHY DE VEDADO REMIX 12. ARROZ CON POLLO / CARL COX MIX BONUS TRACKS 12. ROFOROFO FIGHT (LOUIE VEGA’S REMIX) 13. LAGRIMAS DE SOLEDAD (NO EXISTEN PALABRAS) D’WALA REMIX 14. CHEKERE SON (ALEX PATCHWORK REMIX) + GILLES PETERSON PRESENTS THE MAKING OF HAVANA CULTURA 15. LAGRIMAS DE SOLEDAD (NO EXISTEN PALABRAS) VINCE VELLA REMIX A 12 MINUTE DOCUMENTARY FOREWORD When the opportunity to travel to Cuba and check out the new generation of Havana-based artists popped up in September 2008, I grabbed it with both hands. -

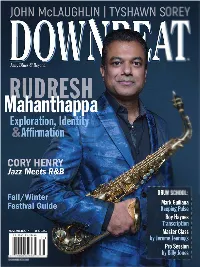

Chicago Jazz Festival Spotlights Hometown

NOVEMBER 2017 VOLUME 84 / NUMBER 11 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Managing Editor Brian Zimmerman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Markus Stuckey Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Hawkins Editorial Intern Izzy Yellen ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Kevin R. Maher 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Richard Seidel, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian, -

Emilie Chick

EMILIE CHICK © STÉPHANE GINER. All rights reserved. PRESS KIT 2012 BIOGRAPHY "I love Emilie Chick… …but I can’t pin down her style..." © NASSIRA BELMEKKI. All rights reserved. It is hard to define Emilie Chick’s music: hip-hop, swing, electro, pop, soul? It’s as if choosing one genre would deprive her of all the others. While the quartet remains groovy, it ventures out into daring pop arrangements, on which Emilie’s voice navigates like the bad-girl, crooner, spoken word, jazz diva that she alternatively is. Gilles Peterson, the English musical pope, loved her so much he named her Winner and Revelation of his 2008 Worldwide Festival. In 2010 she released her 1st solo album, precisely mixing all her influences, very urban, and was awarded the « Best Album » Prize by the European Musical Press at the Europavox/Adami/Deezer de Talents competition in 2010. Since then, a variety of great producers have remixed her tracks. Currently adding the finishing touches to her next album, Emilie has settled in the South of France where she and her band were pre-selected for the 2012 edition of the famous emerging artists Festival “Printemps de Bourges”. Promising isn’t it? LIVE - 2012 07/09 – INAUGURATION OF PALOMA, Nîmes (w/ DJ Shadow, Death in Vegas, Juan Rozoff & Phyltre) 21/07 – FESTIVAL “LA PLEINE LUNE”, Payzac (w/ 1995, The Shoes & Le Peuple de L’Herbe) 13/07 – FESTIVAL “LIVES AU PONT”, Pont du Gard (w/ De La Soul, Selah Sue, Breakbot & Birdy Nam Nam) 21/06 – LA FETE DE LA MUSIQUE DU DOMAINE D’O, Montpellier 17/06 – LES PETITES DECIBELS AU PRESTO, -

The Year's Best Music Marketing Campaigns

DECEMBER 11 2019 sandboxMUSIC MARKETING FOR THE DIGITAL ERA ISSUE 242 thE year’s best music marketing campaigns SANDBOX 2019 SURVEY thE year’s best music marketing campaigns e received a phenomenal Contents 15 ... THE CINEMATIC ORCHESTRA 28 ... KIDD KEO 41 ... MARK RONSON number of entries this year and 03 ... AFRO B 16 ... DJ SHADOW 29 ... KREPT & KONAN 42 ... RICK ROSS had to increase the shortlist W 17 ... BILLIE EILISH 30 ... LAUV 43 ... SAID THE WHALE 04 ... AMIR to 50 in order to capture the quality 05 ... BASTILLE 18 ... BRIAN ENO 31 ... LD ZEPPELIN 44 ... SKEPTA and breadth of 2019’s best music campaigns. 06 ... BEE GEES 19 ... FEEDER 32 ... SG LEWIS 45 ... SLIPKNOT We had entries from labels of all 07 ... BERET 20 ... DANI FERNANDEZ 33 ... LITTLE SIMZ 46 ... SAM SMITH sizes around the world and across 08 ... BIG K.R.I.T. 21 ... FLOATING POINTS 34 ... MABEL 47 ... SPICE GIRLS a vast array of genres. As always, 09 ... BON IVER 22 ... GIGGS 35 ... NSG 48 ... SUPERM campaigns are listed in alphabetical 10 ... BRIT AWARDS 2019 23 ... HOT CHIP 36 ... OASIS 49 ... THE 1975 order, but there are spot prizes 11 ... BROKEN SOCIAL SCENE 24 ... HOZIER 37 ... ANGEL OLSEN 50 ... TWO DOOR CINEMA CLUB throughout for the ones that we felt 12 ... LEWIS CAPALDI 25 ... ELTON JOHN 38 ... PEARL JAM 51 ... UBBI DUBBI did something extra special. Here are 13 ... CHARLI XCX 26 ... KANO 39 ... REGARD 52 ... SHARON VAN ETTEN 2019’s best in show. 14 ... CHASE & STATUS 27 ... KESHA 40 ... THE ROLLING STONES 2 | sandbox | ISSUE 242 | 11.12.19 SANDBOX 2019 SURVEY AFRO B MARATHON MUSIC GROUP specifically focusing on Sweden, Netherlands, Ghana, Nigeria, the US and France. -

Sa-Ra Creative Partners “ Double Dutch / Death of a Star ” First Single Released November 9, 2004

SA-RA CREATIVE PARTNERS “ DOUBLE DUTCH / DEATH OF A STAR ” FIRST SINGLE RELEASED NOVEMBER 9, 2004. DEBUT ALBUM TO BE RELEASED IN 2005 Following their production work for Jill Scott, Erykah Badu, Common, Dr. Dre, Heavy D, Pharoahe Monche, Bilal, Jurassic 5, Foxy Brown, Killer Mike (outkast camp), and many others including work on J-Lo's current album, the SA-RA Creative Partners present their debut single on Ubiquity with an album to follow in 2005. Fans of the Neptunes, Outkast, Jay Dee, Prince & Sly Stone hold tight, this sh-- is truly cosmic! (2004) JOHN PEEL AWARD WINNER (BBC RADIO 1 GILLES PETERSON ‘WORLDWIDE’ AWARDS) CONFIRMED PRESS COVERAGE TO DATE: “SA-RA IS DOPE!” Straight No Chaser (Cover Story), Dazed & PHARRELL Confused, The Fader, The Observer, Bbc Collec- “SA-RA WILLIAMS tive, Echoes, Undercover, Warp (Japan), Juice NOW! THAT’SIS MY SH-- ALL RIGHTI’M (Germany), RE:UP, International DJ, Yellow Rat LISTEN KANYE WEST Bastard, XLR8R, Keyboard, Tokion, NV Maga- “HOW MAN ING TO” zine, The Ave, Flaunt, Miami New Times, Soma, SAY THEY PRODUCE B-Informed, URB Next 100 (2005) Y PEOPLE CAN DR. DRE RECENT APPEARANCES: ME?” - Taz Arnold From SA-RA Creative Partners featured In Common’s New Video ‘The Corner’ directed By Kanye West - The Roots Pre-Grammy Party (Los Angeles) RADIO/PRESS CONTACT: - Los Angeles Natural History Museum Showcase AARON MICHELSON - New Years Eve @ Electric Factory (Philadelphia) with The Roots, Black Sheep & Rahzel [email protected] - 2004 Worldwide Awards Show (December 15 @ Cargo, London) (949) 764-9012 EXT. 14 - Sway & Tech Guest Appearance WWW.UBIQUITYRECORDS.COM - Gilles Peterson ‘Worldwide’ One Hour Special (BBC Radio 1) WWW.SA-RA.NET - Benji B ‘Deviation’ One Hour Interview (BBC Radio 1xtra) - 2004 Red Bull Music Academy Featured Speaker - Distortion 2 Static Interview (WB 20, San Francisco) MANAGEMENT: - Live Performance With Roberta Flack For Trace Magazine JARRET MEYER, RAWKUS ENT.