The Jazz Dance Scene

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Benny L Scores Beatport's First-Ever Drum & Bass No. 1

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE BENNY L SCORES BEATPORT’S FIRST-EVER DRUM & BASS NO. 1 BERLIN, DE - January 17, 2019 - London-based DJ and producer Benny L has made Beatport history with the first-ever Drum & Bass track to reach No. 1 on the store’s overall Top 100. Released January 11, exclusively on Beatport, Benny L’s remix of the John Holt reggae classic ‘Police In Helicopter’ swiftly hit No. 1 in Drum & Bass. From there, it climbed to the overall No. 1 spot, leading a Top 10 otherwise dominated by Beatport’s various house and techno genres. The genre’s first-ever Beatport No. 1 comes via London’s long-running Hospital Records as part of its ‘Sick Music 2019’ series, which also features releases from scene luminaries such as London Elektricity, Fred V and Logistics. Benny L, whose releases have previously appeared on labels like Metalheadz and AudioPorn Records, won Best Newcomer at the recent Drum&BassArena Awards. His ‘Police In Helicopter’ remix started life as a much in-demand dubplate, which he shared with only a select few peers. After building steam in the sets of bass heavyweights last summer, its official release was keenly anticipated by DJs. "Hospital hit me up about doing a remix for a forthcoming project and ‘Police In Helicopter’ was on the list, so I went for it,” Benny L explained to Beatport. “It all came together pretty quickly, and I was very happy with the mixdown.” “Even after a few months, the reaction was incredible, with DJs such as Randall, Shy FX, Andy C and Friction playing it,” he added. -

BTN6916 LMW NORTHERN SOUL ENTS GUIDE SK.Indd

22-25 SEPT 2017 20-23 SEPT 2019 SKEGNESS RESORT GLORIACELEBRATING 60 YEARS JONES OF MOTOWN BOBBY BROOKS WILSON BRENDA HOLLOWAY EDDIE HOLMAN CHRIS CLARK THE FLIRTATIONS TOMMY HUNT THE SIGNATURES FT. STEFAN TAYLOR PAUL STUART DAVIES•JOHNNY BOY PLUS MANY MORE WELCOME TO THE HIGHLIGHTS As well as incredible headliners and legendary DJs, there are loads WORLD’S BIGGEST AND more soulful events to get involved in: BEST NORTHERN SOUL ★ Dance competition with Russ Winstanley and Sharon Sullivan ★ Artist meet and greets SURVIVORS WEEKENDER ★ Shhhh... Battle of the DJs Silent Disco ★ Tune in to Northern Soul BBC – Butlin’s Broadcasting Company Original Wigan Casino jock and founder of the Soul Survivors Weekender, with Russ! Russ Winstanley, has curated another jam-packed few days for you. It’s an ★ incredible line-up with soul legends fl own in from around the world plus a Northern Soul Awards and Dance Competition host of your favourite soul spinners. We’re celebrating Motown Records 60th Anniversary in 2019. To mark this special occasion we have some of the original Motown ladies gracing the stage to celebrate this milestone birthday. SATURDAY 14.00 REDS Meet and Greet with Eddie Holman, Bobby Brooks Wilson, Tommy Hunt Brenda Holloway, Chris Clark and Gloria Jones will also be joining us for a Q&A session, together with Motown afi cionado, Sharon Davies, on Sunday afternoon in Reds. Not to be missed!! SUNDAY 14.00 REDS Don’t miss the Northern Soul dance classes, DJ Battles, Northern Soul Q&A with Brenda Holloway, Chris Clark, Gloria Jones and Sharon Davis awards and dance competitions across the weekend and be sure to look Hosted by Russ Winstanley and Ian Levine, followed by a meet and greet out for limited edition, souvenir vinyl and merch in the Skyline record stall. -

Music Video As Black Art

IN FOCUS: Modes of Black Liquidity: Music Video as Black Art The Unruly Archives of Black Music Videos by ALESSANDRA RAENGO and LAUREN MCLEOD CRAMER, editors idway through Kahlil Joseph’s short fi lm Music Is My Mis- tress (2017), the cellist and singer Kelsey Lu turns to Ishmael Butler, a rapper and member of the hip-hop duo Shabazz Palaces, to ask a question. The dialogue is inaudible, but an intertitle appears on screen: “HER: Who is your favorite fi lm- Mmaker?” “HIM: Miles Davis.” This moment of Black audiovisual appreciation anticipates a conversation between Black popular cul- ture scholars Uri McMillan and Mark Anthony Neal that inspires the subtitle for this In Focus dossier: “Music Video as Black Art.”1 McMillan and Neal interpret the complexity of contemporary Black music video production as a “return” to its status as “art”— and specifi cally as Black art—that self-consciously uses visual and sonic citations from various realms of Black expressive culture in- cluding the visual and performing arts, fashion, design, and, obvi- ously, the rich history of Black music and Black music production. McMillan and Neal implicitly refer to an earlier, more recogniz- able moment in Black music video history, the mid-1990s and early 2000s, when Hype Williams defi ned music video aesthetics as one of the single most important innovators of the form. Although it is rarely addressed in the literature on music videos, the glare of the prolifi c fi lmmaker’s infl uence extends beyond his signature lumi- nous visual style; Williams distinguished the Black music video as a creative laboratory for a new generation of artists such as Arthur Jafa, Kahlil Joseph, Bradford Young, and Jenn Nkiru. -

Effets & Gestes En Métropole Toulousaine > Mensuel D

INTRAMUROSEffets & gestes en métropole toulousaine > Mensuel d’information culturelle / n°383 / gratuit / septembre 2013 / www.intratoulouse.com 2 THIERRY SUC & RAPAS /BIENVENUE CHEZ MOI présentent CALOGERO STANISLAS KAREN BRUNON ELSA FOURLON PHILLIPE UMINSKI Éditorial > One more time V D’après une histoire originale de Marie Bastide V © D. R. l est des mystères insondables. Des com- pouvons estimer que quelques marques de portements incompréhensibles. Des gratitude peuvent être justifiées… Au lieu Ichoses pour lesquelles, arrivé à un certain de cela, c’est souvent l’ostracisme qui pré- cap de la vie, l’on aimerait trouver — à dé- domine chez certains des acteurs culturels faut de réponses — des raisons. Des atti- du cru qui se reconnaîtront. tudes à vous faire passer comme étranger en votre pays! Il faut le dire tout de même, Cependant ne généralisons pas, ce en deux décennies d’édition et de prosély- serait tomber dans la victimisation et je laisse tisme culturel, il y a de côté-ci de la Ga- cet art aux politiques de tous poils, plus ha- ronne des décideurs/acteurs qui nous biles que moi dans cet exercice. D’autant toisent quand ils ne nous méprisent pas tout plus que d’autres dans le métier, des atta- simplement : des organisateurs, des musi- ché(e)s de presse des responsables de ciens, des responsables culturels, des théâ- com’… ont bien compris l’utilité et la néces- treux, des associatifs… tout un beau monde sité d’un média tel que le nôtre, justement ni qui n’accorde aucune reconnaissance à inféodé ni soumis, ce qui lui permet une li- photo © Lisa Roze notre entreprise (au demeurant indépen- berté d’écriture et de publicité (dans le réel dante et non subventionnée). -

Benny Sings - City Pop 22 February 2019

Benny Sings - City Pop 22 February 2019 “For more than 10 years, fans have been drawn to Dutch singer-songwriter Benny Sings' ability to layer R&B, jazz and pop over hip-hop foundations.” — NPR Music Benny Sings will release City Pop, his sixth album and first for Stones Throw in February 2019. With his signing to Stones Throw, he joins the label’s roster of artists — such as Jerry Paper and Mild High Club — in making music at the intersection of jazz, AOR, R&B and soul. On City Pop, he delivers real-life observations and insights on love, holding together soft rock-inspired songwriting and jazz instrumentation with his leading piano and distinctive vocal. The album was inspired by and written in cities all over the world, including New York, LA, Tokyo, Paris and Benny’s hometown of Amsterdam. Benny Sings debuted in 2003 with Champagne People. Since then he has performed for NPR’s Tiny Desk (their only Dutch guest to date); toured the world with Mayer Hawthorne, and collaborated with the likes of Anderson .Paak, GoldLink, and Mndsgn. In 2017 he co-wrote and featured on Rex Orange County’s megahit “Loving Is Easy”, a collaboration that arose from mutual admiration: "Benny has always been a massive inspiration for me and my music,” says the BBC Sound of 2018 breakout star, “In my opinion he’s one of the most underrated producers and artists going.” Like the 2015 album Studio, City Pop celebrates collaboration, with Hawthorne, Cornelius, Sukima switch (the “Japanese Steely Dan”), Mocky and Faberyayo among the featured artists. -

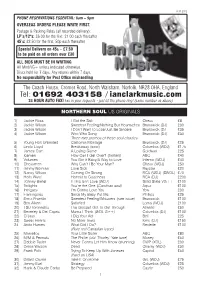

Clarky List 50 31/07/2012 13:06 Page 1

Clarky List 51_Clarky List 50 31/07/2012 13:06 Page 1 JULY 2012 PHONE RESERVATIONS ESSENTIAL : 8am – 9pm OVERSEAS ORDERS PLEASE WRITE FIRST. Postage & Packing Rates (all recorded delivery): LP’s/12"s: £6.00 for the first, £1.00 each thereafter 45’s: £2.50 for the first, 50p each thereafter Special Delivery on 45s – £7.50 to be paid on all orders over £30 ALL BIDS MUST BE IN WRITING All Mint/VG+ unless indicated otherwise. Discs held for 7 days. Any returns within 7 days. No responsibility for Post Office mis han dling The Coach House, Cromer Road, North Walsham, Norfolk, NR28 0HA, England Tel: 01692 403158 / ianclarkmusic.com 24 HOUR AUTO FAX! Fax in your requests - just let the phone ring! (same number as above) NORTHERN SOUL US ORIGINALS 1) Jackie Ross I Got the Skill Chess £8 2) Jackie Wilson Sweetest Feeling/Nothing But Heartaches Brunswick (DJ) £30 3) Jackie Wilson I Don’t Want to Lose/Just Be Sincere Brunswick (DJ £35 4) Jackie Wilson Who Who Song Brunswick (DJ) £30 Three rare promos of these soul classics 5) Young Holt Unlimited California Montage Brunswick (DJ) £25 6) Linda Lloyd Breakaway (swol) Columbia (WDJ) £175 7) James Carr A Losing Game Goldwax £25 8) Icemen How Can I Get Over? (brilliant) ABC £40 9) Volumes You Got it Baby/A Way to Love Inferno (WDJ) £40 10) Chessmen Why Can’t I Be Your Man? Chess (WDJ) £50 11) Jimmy Norman Love Sick Raystar £20 12) Nancy Wilcox Coming On Strong RCA (WDJ) (SWOL) £70 13) Herb Ward Honest to Goodness RCA (DJ) £200 14) Johnny Bartel If This Isn’t Love (WDJ) Solid State VG++ £100 15) Twilights -

Hip-Hop's Diversity and Misperceptions

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Honors College Summer 8-2020 Hip-Hop's Diversity and Misperceptions Andrew Cashman Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors Part of the Music Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HIP-HOP’S DIVERSITY AND MISPERCEPTIONS by Andrew Cashman A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for a Degree with Honors (Anthropology) The Honors College University of Maine August 2020 Advisory Committee: Joline Blais, Associate Professor of New Media, Advisor Kreg Ettenger, Associate Professor of Anthropology Christine Beitl, Associate Professor of Anthropology Sharon Tisher, Lecturer, School of Economics and Honors Stuart Marrs, Professor of Music 2020 Andrew Cashman All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT The misperception that hip-hop is a single entity that glorifies wealth and the selling of drugs, and promotes misogynistic attitudes towards women, as well as advocating gang violence is one that supports a mainstream perspective towards the marginalized.1 The prevalence of drug dealing and drug use is not a picture of inherent actions of members in the hip-hop community, but a reflection of economic opportunities that those in poverty see as a means towards living well. Some artists may glorify that, but other artists either decry it or offer it as a tragic reality. In hip-hop trends build off of music and music builds off of trends in a cyclical manner. -

“Rapper's Delight”

1 “Rapper’s Delight” From Genre-less to New Genre I was approached in ’77. A gentleman walked up to me and said, “We can put what you’re doing on a record.” I would have to admit that I was blind. I didn’t think that somebody else would want to hear a record re-recorded onto another record with talking on it. I didn’t think it would reach the masses like that. I didn’t see it. I knew of all the crews that had any sort of juice and power, or that was drawing crowds. So here it is two years later and I hear, “To the hip-hop, to the bang to the boogie,” and it’s not Bam, Herc, Breakout, AJ. Who is this?1 DJ Grandmaster Flash I did not think it was conceivable that there would be such thing as a hip-hop record. I could not see it. I’m like, record? Fuck, how you gon’ put hip-hop onto a record? ’Cause it was a whole gig, you know? How you gon’ put three hours on a record? Bam! They made “Rapper’s Delight.” And the ironic twist is not how long that record was, but how short it was. I’m thinking, “Man, they cut that shit down to fifteen minutes?” It was a miracle.2 MC Chuck D [“Rapper’s Delight”] is a disco record with rapping on it. So we could do that. We were trying to make a buck.3 Richard Taninbaum (percussion) As early as May of 1979, Billboard magazine noted the growing popularity of “rapping DJs” performing live for clubgoers at New York City’s black discos.4 But it was not until September of the same year that the trend gar- nered widespread attention, with the release of the Sugarhill Gang’s “Rapper’s Delight,” a fifteen-minute track powered by humorous party rhymes and a relentlessly funky bass line that took the country by storm and introduced a national audience to rap. -

Glastonburyminiguide.Pdf

GLASTONBURY 2003 MAP Produced by Guardian Development Cover illustrations: John & Wendy Map data: Simmons Aerofilms MAP MARKET AREA INTRODUCTION GETA LOAD OF THIS... Welcome to Glastonbury 2003 and to the official Glastonbury Festival Mini-Guide. This special edition of the Guardian’s weekly TV and entertainments listings magazine contains all the information you need for a successful and stress-free festival. The Mini-Guide contains comprehensive listings for all the main stages, plus the pick of the acts at Green Fields, Lost and Cabaret Stages, and advice on where to find the best of the weird and wonderful happenings throughout the festival. There are also tips on the bands you shouldn’t miss, a rundown of the many bars dotted around the site, fold-out maps to help you get to grips with the 600 acres of space, and practical advice on everything from lost property to keeping healthy. Additional free copies of this Mini-Guide can be picked up from the Guardian newsstand in the market, the festival information points or the Workers Beer Co bars. To help you keep in touch with all the news from Glastonbury and beyond, the Guardian and Observer are being sold by vendors and from the newsstands at a specially discounted price during the festival . Whatever you want from Glastonbury, we hope this Mini-Guide will help you make the most of it. Have a great festival. Watt Andy Illustration: ESSENTIAL INFORMATION INFORMATION POINTS hygiene. Make sure you wash MONEY give a description. If you lose There are five information your hands after going to the loo The NatWest bank is near the your children, ask for advice points where you can get local, and before eating. -

27Th April 2018

27th April 2018 The information contained within this announcement is deemed by the Company to constitute inside information stipulated under the Market Abuse Regulation (EU) No. 596/2014. Upon the publication of this announcement via the Regulatory Information Service, this inside information is now considered to be in the public domain. EVR Holdings plc (‘EVR’ or the ‘Company’) EVR Holdings Signs Agreements with Record Labels and Music Publishers EVR Holdings plc (AIM: EVRH), the leading creator of virtual reality music content and its subsidiary MelodyVR Ltd (‘MelodyVR’) are pleased to announce that on 26 April 2018 MelodyVR entered into the following multi-year agreements: 1. Publishing Agreement with Kobalt (Kobalt Music Publishing America, Inc.) and AMRA (American Music Rights Association). Kobalt Music publishing represents the rights of songwriters and artists such as Alt-J, Beck, Fleetwood Mac, Gwen Stefani, Jack Garratt, Lionel Richie, Moby, Nick Cave and The Bad Seeds, Nine Inch Nails, Placebo, Queens Of The Stone Age, Rudimental and many more. 2. Record Label Agreement with Cooking Vinyl (Cooking Vinyl Limited). Cooking Vinyl represents musicians such as Alison Moyet, Goldie, Groove Armada, James, Madness, Marilyn Manson, The Fratellis, The Prodigy, Underworld and many more. 3. Record Label Agreement with Red Bull Records (Red Bull Records Inc.) Red Bull Records represents artists such as AWOLNATION, The Aces, Black & Gold, Beartooth, Five Knives and Itch. 4. Publishing Agreement with AKM (AKM Autoren, Komponisten und Musikverleger) and Austro Mechana. AKM/Austro mechana administers the performance, reproduction and distribution rights in musical works from composers and music publishers in Austria. 5. Record Label agreement with Hospital Records (Hospital Records Limited) and Publishing agreement with Hospital Records (Songs In The Key Of Knife T/A Hospital Records Limited). -

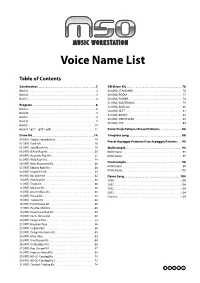

M50 Voice Name List

Voice Name List Table of Contents Combination . .2 GM Drum Kit . 76 Bank A. .2 48 (GM): STANDARD . 76 Bank B. .3 49 (GM): ROOM . 77 Bank C. .4 50 (GM): POWER. 78 51 (GM): ELECTRONIC . 79 Program . .6 52 (GM): ANALOG . 80 Bank A. .6 53 (GM): JAZZ . 81 Bank B. .7 54 (GM): BRUSH . 82 Bank C. .8 55 (GM): ORCHESTRA. 83 Bank D . .9 56 (GM): SFX . 84 Bank E . 10 Bank G / g(1)…g(9) / g(d). 11 Drum Track Patterns/Preset Patterns. 86 Drum Kit . .14 Template song . 88 00 (INT): Studio Standard Kit. 14 Preset Arpeggio Patterns/User Arpeggio Patterns . 90 01 (INT): Funk Kit. 16 02 (INT): Jazz/Brush Kit . 18 Multisample. 94 03 (INT): B.Real Rap Kit . 20 ROM mono . 94 04 (INT): Acoustic Pop Kit. 22 ROM stereo . 97 05 (INT): Wild Rock Kit . 24 Drumsample . 98 06 (INT): New Processed Kit. 26 07 (INT): Electro Rock Kit . 28 ROM mono . 98 08 (INT): Insane FX Kit . 30 ROM stereo . 103 09 (INT): Nu Style Kit . 32 Demo Song. 104 10 (INT): Hip Hop Kit . 34 S000 . 104 11 (INT): Tricki kit. 36 S001 . 104 12 (INT): Mashed Kit. 38 S002 . 104 13 (INT): Drum'n'Bass Kit . 40 S003 . 104 14 (INT): House Kit . 42 Cue List . 104 15 (INT): Trance Kit . 44 16 (INT): Hard House Kit . 46 17 (INT): Psycho-Chill Kit . 48 18 (INT): Down Low Rap Kit. 50 19 (INT): Orch.-Ethnic Kit . 52 20 (INT): Original Perc . 54 21 (INT): Brazilian Perc. 56 22 (INT): Cuban Perc . -

Music As a Cultural System: Sensibility and Interpretation

Music as a Cultural System: Sensibility and Interpretation Ian Maxwell On Interpretation My favourite Borges fable is that of Pierre Menard, the man who wanted to rewrite Don Quixote. Menard’s ambition, Borges recounts in his dry parody of literary criticism, was not merely to reproduce Cervantes’s work, but to do so spontaneously: to (re)write the Quixote not by a labour of research, nor by somehow mystically channeling the original author, but as an act of original creativity. By the end of the story Menard has succeeded, in part, producing several word-perfect passages. In the final pages of the story, Borges subjects two identical passages, one written in seventeenth-century Spain, and the other in early twentieth-century France, to a comparative analysis. Breathtakingly, Borges is able to produce compelling, and utterly discordant, interpretations of the two works. His argument—one that anticipates those of the post-structuralists by decades—is, of course, that context is everything. Texts are unstable, polysemic potentials for meaning, rather than the bearers of extractable truths. In this essay I want to do something similar. I will be writing of those listeners constituting a ‘hip hop community’ in Sydney in the mid-1990s. I will take two recordings that are, for all intents and purposes, identical in terms of instrumentation, structure and stylistic conventions. Each was recorded around the same time, and each circulated in the same milieus. One was the subject of acclaim, the other of disdain. One was considered to be ‘hip hop,’ the other not. My interest is not in aesthetic judgements about the relative worth of each of these recordings.