Introduction a Nigger in the Woodpile, Or Black (In)Visibility in Film History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Light in Darkness, Oscar Micheaux: Entrepreneur Intellectual Agitator Airic Hughes University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 7-2015 A Light in Darkness, Oscar Micheaux: Entrepreneur Intellectual Agitator Airic Hughes University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, African History Commons, American Film Studies Commons, and the American Literature Commons Recommended Citation Hughes, Airic, "A Light in Darkness, Oscar Micheaux: Entrepreneur Intellectual Agitator" (2015). Theses and Dissertations. 1317. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/1317 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. A Light in Darkness, Oscar Micheaux: Entrepreneur Intellectual Agitator A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History By Airic Hughes University of Arkansas Bachelor of Arts in History and African and African American Studies, 2011 July 2015 University of Arkansas This thesis is approved for recommendation to the Graduate Council. __________________ Dr. Calvin White Thesis Director __________________ __________________ Dr. Pearl Ford Dowe Dr. James Gigantino Committee Member Committee Member Abstract: Oscar Micheaux was a luminary who served as an agent of racial uplift, with a unique message to share with the world on behalf of the culturally marginalized African Americans. He produced projects that conveyed the complexity of the true black experience with passion and creative courage. His films empowered black audiences and challenged conventional stereotypes of black culture and potential. -

Index to Volume 26 January to December 2016 Compiled by Patricia Coward

THE INTERNATIONAL FILM MAGAZINE Index to Volume 26 January to December 2016 Compiled by Patricia Coward How to use this Index The first number after a title refers to the issue month, and the second and subsequent numbers are the page references. Eg: 8:9, 32 (August, page 9 and page 32). THIS IS A SUPPLEMENT TO SIGHT & SOUND Index 2016_4.indd 1 14/12/2016 17:41 SUBJECT INDEX SUBJECT INDEX After the Storm (2016) 7:25 (magazine) 9:102 7:43; 10:47; 11:41 Orlando 6:112 effect on technological Film review titles are also Agace, Mel 1:15 American Film Institute (AFI) 3:53 Apologies 2:54 Ran 4:7; 6:94-5; 9:111 changes 8:38-43 included and are indicated by age and cinema American Friend, The 8:12 Appropriate Behaviour 1:55 Jacques Rivette 3:38, 39; 4:5, failure to cater for and represent (r) after the reference; growth in older viewers and American Gangster 11:31, 32 Aquarius (2016) 6:7; 7:18, Céline and Julie Go Boating diversity of in 2015 1:55 (b) after reference indicates their preferences 1:16 American Gigolo 4:104 20, 23; 10:13 1:103; 4:8, 56, 57; 5:52, missing older viewers, growth of and A a book review Agostini, Philippe 11:49 American Graffiti 7:53; 11:39 Arabian Nights triptych (2015) films of 1970s 3:94-5, Paris their preferences 1:16 Aguilar, Claire 2:16; 7:7 American Honey 6:7; 7:5, 18; 1:46, 49, 53, 54, 57; 3:5: nous appartient 4:56-7 viewing films in isolation, A Aguirre, Wrath of God 3:9 10:13, 23; 11:66(r) 5:70(r), 71(r); 6:58(r) Eric Rohmer 3:38, 39, 40, pleasure of 4:12; 6:111 Aaaaaaaah! 1:49, 53, 111 Agutter, Jenny 3:7 background -

A Queer and Gendered Analysis of Blaxploitation Films

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Social and Cultural Sciences Faculty Research and Publications/Department of Social and Cultural Sciences This paper is NOT THE PUBLISHED VERSION; but the author’s final, peer-reviewed manuscript. The published version may be accessed by following the link in the citation below. Western Journal of Black Studies, Vol. 37, No. 1 (2013): 28-38. DOI. This article is © Washington State University and permission has been granted for this version to appear in e- Publications@Marquette. Washington State University does not grant permission for this article to be further copied/distributed or hosted elsewhere without the express permission from Washington State University. Contents Abstract ......................................................................................................................................................... 2 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 2 Literature Review .......................................................................................................................................... 3 Social Identity Theory ............................................................................................................................... 3 The Politics of Semiotics ........................................................................................................................... 4 Creating Racial Identity through Film and -

Department of Cinema and Media Studies 1

Department of Cinema and Media Studies 1 Department of Cinema and Media Studies Department Website: http://cms.uchicago.edu Core Faculty Department Chair - Daniel Morgan Director of Graduate Studies - Allyson Nadia Field, Associate Professor Director of Undergraduate Studies - Salomé Skvirsky, Associate Professor Professors • Robert Bird • James Chandler • Thomas Lamarre • David Levin • Richard Neer • D.N. Rodowick • Jacqueline Stewart Associate Professors • Maria Belodubrovskaya • Patrick Jagoda • Kara Keeling • Rochona Majumdar • Daniel Morgan • Jennifer Wild • Salomé Skvirsky Professor of Practice in the Arts • Judy Hoffman Lecturers • Dominique Bluher • Marc Downie • Thomas Comerford Visiting Faculty & Associated Fellows • Nicholas Baer, Society of Fellows and Collegiate Assistant Professor • Steffen Hven, Post-Doctoral Fellow - Volkswagen Stiftung Fellowship • Gabriel Tonelo, Post-Doctoral Fellow - Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP) Affiliated Faculty • Lauren Berlant, Department of English Language and Literature • James Conant, Department of Philosophy • Berthold Hoeckner, Department of Music • Paola Iovene, East Asian Languages and Civilizations • Loren Kruger, Department of English Language and Literature • Laura Letinsky, Department of Visual Arts • Constantine Nakassis, Department of Anthropology • Robert Pippin, Department of Philosophy • Malynne Sternstein, Department of Slavic Languages and Literature • Catherine Sullivan, Department of Visual Arts Emeritus Faculty 2 Department of Cinema and Media -

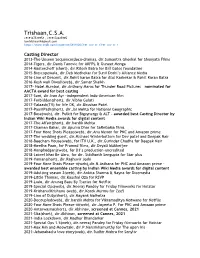

Trishaan,C.S.A. +919167549854 , +919372625905 [email protected]

Trishaan,C.S.A. +919167549854 , +919372625905 [email protected] https://www.imdb.com/name/nm5811800/?ref_=nv_sr_1?ref_=nv_sr_1 Casting Director 2013-The Unseen Sequence(docu-drama), dir.Sumantra Ghoshal for Shunyata Films 2014-Tigers, dir.Danis Tanovic for AKFPL & Guneet Monga 2014-Mastercheff (short), dir.Ritesh Batra for Bill Gates foundation 2015-Bioscopewala, dir.Deb Medhekar for Sunil Doshi’s Alliance Media 2016-Line of Descent, dir.Rohit karan Batra for Atul Kasbekar & Rohit Karan Batra 2016-Kosh wali Diwali(web), dir.Samar Shaikh 2017- Hotel Mumbai, dir.Anthony Maras for Thunder Road Pictures – nominated for AACTA award for best casting 2017-Soni, dir.Ivan Ayr –independent Indo-American film 2017-Forbidden(short), dir.Vibha Gulati 2017-Talaash(TV) for life OK, dir.Bhushan Patel 2017-PaaniPath(short), dir.Jai Mehta for National Geographic 2017-Bose(web), dir. Pulkit for Bigsynergy & ALT – awarded best Casting Director by Indian Wiki Media awards for digital content 2017-The Affair(short), dir.hardik Mehta 2017-Chaman Bahar, dir.Apurva Dhar for SaReGaMa films 2017-Four More Shots Please(web), dir.Anu Menon for PNC and Amazon prime 2017-The wedding guest, dir.Michael Winterbottom for Dev patel and Deepak Nair 2018-Beecham House(web), for ITV U.K., dir.Gurinder Chadha for Deepak Nair 2018-Meetha Paan, for Pramod films, dir.Deyali Mukherjee 2018-Manphodganj(web), for DJ’s production-uncredited 2018-Lateef bhai Be-Abru, for dir. Siddharth Sengupta for Star plus 2019-Yaman(short), dir.Raghuvir Joshi 2019-Four More Shots Please-ii(web),dir.N.Asthana -

Download Download

EDITORIAL NOTES Editors’ Preface Lynette Hunter, Alex Lichtenfels, Heather Nolan, and John Zibell Copresence with the Camera emerged through a series of ongoing conversations between politically motivated artists. These conversations started informally, between collaborators at various events, exhibitions, and conferences, and among colleagues and friends working on filmmaking and critical approaches to working with a camera. Over three years of listening to and talking with each other, unexpected resonances between artistic practices led to collaborations that were proposed and later actualized, and to excitement over the revelation of common goals. Together, we felt there was an opportunity to put together a collection of critically engaged artists’ writings and documents about the art we were and are still making, and this is the work this journal issue continues. It is our intention that these pieces exist in a dialogue with both one another and the works that they document. The relationship between artmaking practice and academic writing is complex. However, we firmly believe that reading a piece about a work can never provide an adequate substitute for experiencing the work itself. For this reason, where it is feasible and appropriate, we have provided links to the works that have been written about, and we encourage you to watch them alongside their documents. The exploration of these conversations in the materials of this journal is intended to be both stimulating and constructive in whatever field of creative practice you may work, or indeed if you are reading for general interest. Aside from these contexts of working with a camera, one element that has consistently motivated us to put together this journal issue is that it is often a great pleasure to learn about how artists make their work—what they do and why, and how it affects both them and their audiences. -

"Race Movies" Visionary: SPENCER WILLIAMS and the Blood of Jesus a Screening and Talk with JACQUELINE STEWART

FILM AT REDCAT PRESENTS Mon Apr 27 |8:30 pm| Jack H. Skirball Series $11 [members $9] "Race Movies" Visionary: SPENCER WILLIAMS and The Blood of Jesus A Screening and Talk with JACQUELINE STEWART Spencer Williams (1893–1969) was, along with Oscar Micheaux, among the very first African American directors of independent features. His great cultural morality tale, The Blood of Jesus (1941, 57 min.), is a landmark of American cinema. Still known primarily as an screen actor (Andy on the Amos ’n’ Andy television series), Williams made more than a dozen films with all-black casts. The Blood of Jesus was a huge hit with African American audiences for years. A story of sin and redemption, the film’s vivid depiction of spiritualism and folk beliefs has a power that few big-budget movies have ever achieved. Scholar Jacqueline Stewart, who is preparing a biography of Williams, will introduce the work and give a talk on the filmmaker’s life and career. In person: Jacqueline Stewart “A masterpiece of folk cinema that has scarcely lost its power to astonish.” – J. Hoberman The Blood of Jesus was the second film directed by Spencer Williams, one of the few African American directors of the 1940s. Williams began his career in the 1920s as an extra, and was later able to move up into writing scripts for all-black short comedies produced by the Al Christie studio. In 1928 he directed the silent film Tenderfeet, which was released by Midnight Productions. In 1939, he wrote two screenplays for the race film genre, the Western Harlem Rides the Range and the horror-comedy Son of Ingagi, and he also acted in these films. -

The British Avant-Garde Film, 1926-1995

IVERS TON PREl Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2019 with funding from Kahle/Austin Foundation https://archive.org/details/britishavantgardOOOOunse 1 926 TO 199 1926 TO 199 AN ANTHOLOGY OF WRITINGS EDITED BY MICHAEL O’PRAY UNIVERSITY lEi LUTON PRESS THE ARTS COUNCIL OF ENGLAND British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this page is available from the British Library ISBN: 1 86020 004 4 Published by John Libbey Media Faculty of Humanities University of Luton 75 Castle Street, Luton, Bedfordshire LU1 3AJ England ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Will Bell at the Arts Council of England for not only his unstinting support but also for his patience and good humour in the face of a deadline-breaking editor. I’d also like to thank David Curtis for his support and his archives, Peter Gidal for his unfailing encouragement, and Nicky Hamlyn for talking through some of the issues with me. I’d also like to thank David Robinson for his permission to use Lindsay Anderson’s essay on Jennings. Thanks also to Roma Gibson at the British Film Institute, Julia Knight and Professor Maggie Humm. As always I’m grateful to Judith Preece, Nikki Bainsfair and Jak Measure at the School of Art and Design Library, University of East London for their friendly assistance and hospitality. I’d also like to thank Gabrielle Dolan and Phil Davies for their friendship during the stitching together of the book, and Phil especially for his computer karma. My thanks to my colleague Gillian Elinor and her husband Jonathan for the generous use of their Welsh retreat. -

American Cinema Is Over 125 Years Old, and African Americans Have Been a Part of It from the Beginning

American cinema is over 125 years old, and African Americans have been a part of it from the beginning. This participation has often been fraught, stymied, and curtailed, but the desire to use motion pictures to craft a self-image has motivated African American filmmakers and performers since the medium’s emergence. At last a fuller picture of this long and intricate history is coming into public awareness. What Kino Classics has given us in Pioneers of African American Cinema—a series of thirty-four films, fragments, and other material expertly curated by scholars Charles Musser and Jacqueline Najuma Stewart, released in 2016, and now playing on the Criterion Channel—is a rich testament to the range of films produced primarily for segregated black audiences in the first half of the twentieth century. Known as “race films,” these movies featured mainly all-black casts and many were made by black filmmakers, answering the need for a self-determined cinematic image that was keenly felt at the time. In 1920, Lester Walton, the arts critic for the African American newspaper the New York Age, championed the innovative “race promoters” who had been endeavoring to “depict our men and women in a favorable light and as they really are; not solely as hewers of wood and drawers of water and using a dialect foreign to the average colored American.” The results were varied and often controversial, but race films shared a fundamental premise: instead of using their black subjects as props or objects of ridicule, these films placed their lives front and center. -

Colorblindness, a Life: Race, Film and the Articulation of an Ideology by Justin Daniel Gomer a Dissertation Submitted in Parti

Colorblindness, A Life: Race, Film and the Articulation of an Ideology By Justin Daniel Gomer A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in African American Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Leigh Raiford, Chair Professor Ula Y. Taylor Professor Darieck Scott Professor Scott Saul Spring 2014 © 2014 by Justin Daniel Gomer All Rights Reserved Abstract Colorblindness, A Life: Race, Film, and the Articulation of an Ideology by Justin Daniel Gomer Doctor of Philosophy in African American Studies University of California, Berkeley Professor Leigh Raiford, Chair My dissertation, entitled, “Colorblindness, A Life: Race, Film, and the Articulation of an Ideology,” offers a political and cultural biography of the racial ideology of colorblindness from its emergence as a coherent racial ideology in the years after the civil rights movement to its dominant influence in social policy in the 1990s. Most importantly, the project reveals the manner in which colorblindness became the racial project of neoliberalism. This elaboration of colorblindness as an ideology and cultural form is best understood through an examination of film during the period of my study. Beginning in the second-half of the 1970s, Hollywood developed its own set of filmic aesthetics, narratives, and tropes that advocated colorblindness. Moreover, Hollywood was not only central to the articulation of the ideology, it also depended upon colorblindness in the New Hollywood era. In the post-civil rights era, then, colorblindness, neoliberalism, and film are constitutive of and inextricable from one another. The project illustrates three key themes. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Critical Crossings: Intersections of Passing and Drag in Popular Culture Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/81j0h4fx Author Marsan, Loran Renee Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Critical Crossings: Intersections of Passing and Drag in Popular Culture A dissertation in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Women’s Studies by Loran Renee Marsan 2012 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Critical Crossings: Intersections of Passing and Drag in Popular Culture by Loran Renee Marsan Doctor of Philosophy in Women’s Studies University of California, Los Angeles, 2012 Professor Juliet Williams, Co-chair Professor Douglas Kellner, Co-chair My dissertation, Critical Crossings: Intersections of Passing and Drag in Popular Culture, offers an innovative study of the political possibilities of two related performative strategies: Drag and Passing. “Drag” refers to the excessive performance of feminine gender, i.e. drag queens, but more recently has been linked to other parodic performances such as blackface. “Passing” originated in the post- and antebellum eras when mixed-race African-Americans passed as white to escape oppressions. It denotes the believable portrayal of another identity, usually racial or gendered. Both have long been topics of media representations. Probing where and how they are used differently in popular culture yields insight into the operation of identity, engaging such issues as the social construction of authenticity, performance, and the “real.” I argue cinema and television have changed how drag and passing are deployed, such that what ii passes for reality and authenticity comes into question while the purposes and functions of drag and passing are also changed. -

Black Struggle Film Production: Meta-Synthesis of Black Struggle Film Production and Critique Since the Millennium

IAFOR Journal of Media, Communication & Film Volume 6 – Issue 1 – Summer 2019 Black Struggle Film Production: Meta-Synthesis of Black Struggle Film Production and Critique Since the Millennium Robert Cummings, Morehouse College, USA Abstract The film industry has historically wrestled with consistently producing representative and innovative Black American wide release feature length theatrical films. The limited quantity of films containing a majority Black cast and films with a Black protagonist allows for exploration of the similarities between such films. “Black struggle films,” films focusing on historic or overt racial, ethnic, or social challenges, appear to be one of the few sorts of films cast, led, and produced by Black American creatives. In addition, Black struggle films appear to be more critically acclaimed and recognized than any other sort of Black film. This investigation is part of a case study on the attributes and successes of Black struggle film production. This article focuses on budget, distribution, and other production variables of Black American films released in the last 20 years. Additionally, a meta-synthesis was performed comparing film critiques of one wide-released, theatrical Black struggle film with other Black films. Film critiques were analyzed using a thematic analytical method to identify themes about their production patterns. The findings of this study will allow media researchers to identify trends in Black American film production and influence producers to engage in strategic and representative production of films that document Black experiences. Keywords: Black struggle film, African American, American film history, White guilt, White savior film, Oscar bait 65 IAFOR Journal of Media, Communication & Film Volume 6 – Issue 1 – Summer 2019 There has been much criticism about the recent 2018 film Green Book (Burke & Farrelly, 2018).