A Queer and Gendered Analysis of Blaxploitation Films

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anti Racism Discussion Guide

ANTI-RACISM DISCUSSION GUIDE Nationwide uprisings against police brutality and movements like Black Lives Matter have brought systemic racism to the forefront—making it imperative for district and school leaders to cultivate anti-racist school systems. Historically, district leaders have focused on multicultural literacy and implicit bias training, but the national conversation has catalyzed a focus on anti-racism. District leaders across the country are asking how they as individuals can (a) examine their own beliefs and actions and (b) foster an environment in which they can push conversations about race, racism, and other equity issues. Although conversations about race pull individuals out of their comfort zones and, at times, lead to conflict and tension between participants, it is important to lead productive discussions about equity issues in your districts and schools. We created this discussion guide to help leaders effectively navigate these topics by establishing goals for equity discussions, brainstorming questions for holding constructive conversations, and identifying actions to take as a result of the perspectives and information shared. I identify how I may unknowingly benefit from racism I promote & advocate DEFINE WHAT YOU for policies & leaders I recognize racism that are anti-racist is a present & current problem I seek out questions HOPE TO EXAMINE that make me I sit with my uncomfortable. discomfort I deny racism is a problem There are several frameworks available in surrounding I speak out I avoid hard I understand my when I see anti-racism research; therefore, it is critical for districts questions own privilege in racism in action to define what they hope to examine. -

Gotham Knights

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 11-1-2013 House of Cards Matthew R. Lieber University of Denver Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd Part of the Screenwriting Commons Recommended Citation Lieber, Matthew R., "House of Cards" (2013). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 367. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/367 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. House of Cards ____________________________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of Social Sciences University of Denver ____________________________ In Partial Requirement of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts ____________________________ By Matthew R. Lieber November 2013 Advisor: Sheila Schroeder ©Copyright by Matthew R. Lieber 2013 All Rights Reserved Author: Matthew R. Lieber Title: House of Cards Advisor: Sheila Schroeder Degree Date: November 2013 Abstract The purpose of this thesis is to approach adapting a comic book into a film in a unique way. With so many comic-to-film adaptations following the trends of action movies, my goal was to adapt the popular comic book, Batman, into a screenplay that is not an action film. The screenplay, House of Cards, follows the original character of Miranda Greene as she attempts to understand insanity in Gotham’s most famous criminal, the Joker. The research for this project includes a detailed look at the comic book’s publication history, as well as previous film adaptations of Batman, and Batman in other relevant media. -

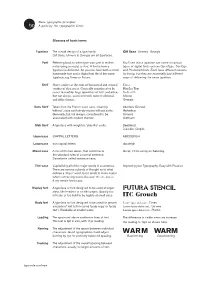

WARM WARM Kerning by Eye for Perfectly Balanced Spacing

Basic typographic principles: A guide by The Typographic Circle Glossary of basic terms Typeface The overall design of a type family Gill Sans Univers Georgia Gill Sans, Univers & Georgia are all typefaces. Font Referring back to when type was cast in molten You’ll see that a typeface can come in various metal using a mould, or font. A font is how a types of digital font; such as OpenType, TrueType typeface is delivered. So you can have both a metal and Postscript fonts. Each have different reasons handmade font and a digital font file of the same for being, but they are essentially just different typeface, e.g Times or Futura. ways of delivering the same typeface. Serif Short strokes at the ends of horizontal and vertical Times strokes of characters. Generally considered to be Hoefler Text easier to read for large quantities of text, and often, Baskerville but not always, associated with more traditional Minion and older themes. Georgia Sans Serif Taken from the French word sans, meaning Akzidenz Grotesk ‘without’, sans serif simply means without serifs. Helvetica Generally, but not always, considered to be Univers associated with modern themes. Gotham Slab Serif A typeface with weightier, ‘slab-like’ serifs. Rockwell Lubalin Graph Uppercase CAPITAL LETTERS ABCDEFGH Lowercase non-capital letters abcdefgh Mixed-case A mix of the two above, that conforms to Great, it’ll be sunny on Saturday. the standard rules of a normal sentence. Sometimes called sentence-case. Title-case Capitalising all of the major words in a sentence. Improving your Typography: Easy with Practice There are various schools of thought as to what defines a ‘major’ word, but it tends to looks neater when connecting words like and, the, to, but, is & my remain lowercase. -

Copyrighted Material

9781405170550_6_ind.qxd 16/10/2008 17:02 Page 432 INDEX 4 Little Girls (1997) 93 action-adventure movie 147, 149, 254, 339, 348, 352, 392–3, 396–7, 8 Mile (2002) 396–7 259, 276, 287–8, 298–9, 410 402–3 20th Century-Fox 21, 30, 34, 40–2, 73, actualities 106, 364, 410 Against All Odds (1984) 289 149, 184, 204–5, 281, 335 ACT-UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Agar, John 268 25th Hour, The (2002) 98 Power) 337, 410 Aghdashloo, Shohreh 75 27 Dresses (2008) 353 ADA (Americans with Disabilities Act) Ahn, Philip 130 28 Days (2000) 293 398–9, 410 AIDS 99, 329, 334, 336–40 48 Hours (1982) 91 Adachi, Jeff 139 AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power see 100-to-1 Shot, The (1906) 174 Adams, Evan 118–19 ACT-UP 300 (2007) 74, 298, 300 ADC (American-Arab Anti- AIM (American Indian Movement) 111, Discrimination Committee) 73–4, 116–17, 410 Abbott and Costello 268 410 Air Force (1943) 268 ABC 340 Addams Family, The (1991) 156 Akins, Zoe 388–9 Abie’s Irish Rose (stage) 57 Addams Family Values (1993) 156 Aladdin (1992) 73–4, 246 Abilities United Productions 384 Adiarte, Patrick 72 Alba, Jessica 76, 155, 159 ability 359–84, 410 adult Western 111, 410 Albert, Eddie 72 ableism 361, 381, 410 Adventures of Ozzie & Harriet, The (TV) Albert, Edward 375 Abominable Dr Phibes, The (1971) 284 Alexie, Sherman 117–18 365 Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Algie, the Miner (1912) 312 Abraham, F. Murray 75, 76 COPYRIGHTEDDesert, The (1994) 348 MATERIALAli (2001) 96 Academy Awards (Oscars) 29, 58, 63, Adventures of Sebastian Cole, The (1998) Alice (1990) 130 67, 72, 75, 83, 92, 93, -

31 Days of Oscar® 2010 Schedule

31 DAYS OF OSCAR® 2010 SCHEDULE Monday, February 1 6:00 AM Only When I Laugh (’81) (Kevin Bacon, James Coco) 8:15 AM Man of La Mancha (’72) (James Coco, Harry Andrews) 10:30 AM 55 Days at Peking (’63) (Harry Andrews, Flora Robson) 1:30 PM Saratoga Trunk (’45) (Flora Robson, Jerry Austin) 4:00 PM The Adventures of Don Juan (’48) (Jerry Austin, Viveca Lindfors) 6:00 PM The Way We Were (’73) (Viveca Lindfors, Barbra Streisand) 8:00 PM Funny Girl (’68) (Barbra Streisand, Omar Sharif) 11:00 PM Lawrence of Arabia (’62) (Omar Sharif, Peter O’Toole) 3:00 AM Becket (’64) (Peter O’Toole, Martita Hunt) 5:30 AM Great Expectations (’46) (Martita Hunt, John Mills) Tuesday, February 2 7:30 AM Tunes of Glory (’60) (John Mills, John Fraser) 9:30 AM The Dam Busters (’55) (John Fraser, Laurence Naismith) 11:30 AM Mogambo (’53) (Laurence Naismith, Clark Gable) 1:30 PM Test Pilot (’38) (Clark Gable, Mary Howard) 3:30 PM Billy the Kid (’41) (Mary Howard, Henry O’Neill) 5:15 PM Mr. Dodd Takes the Air (’37) (Henry O’Neill, Frank McHugh) 6:45 PM One Way Passage (’32) (Frank McHugh, William Powell) 8:00 PM The Thin Man (’34) (William Powell, Myrna Loy) 10:00 PM The Best Years of Our Lives (’46) (Myrna Loy, Fredric March) 1:00 AM Inherit the Wind (’60) (Fredric March, Noah Beery, Jr.) 3:15 AM Sergeant York (’41) (Noah Beery, Jr., Walter Brennan) 5:30 AM These Three (’36) (Walter Brennan, Marcia Mae Jones) Wednesday, February 3 7:15 AM The Champ (’31) (Marcia Mae Jones, Walter Beery) 8:45 AM Viva Villa! (’34) (Walter Beery, Donald Cook) 10:45 AM The Pubic Enemy -

Co-Produced with the Black Film Institute of the University of the District of Columbia the Vision

Co-produced with the Black Film Institute of the University of the District of Columbia the vision. the voice. From LA to London and Martinique to Mali. We bring you the world ofBlack film. Ifyou're concerned about Black images in commercial film and tele vision, you already know that Hollywood does not reflect the multi- cultural nature 'ofcontemporary society. You know thatwhen Blacks are not absent they are confined to predictable, one-dimensional roles. You may argue that movies and television shape our reality or that they simply reflect that reality. In any case, no one can deny the need to take a closer look atwhat is COIning out of this powerful medium. Black Film Review is the forum you've been looking for. Four times a year, we bringyou film criticiSIn froIn a Black perspective. We look behind the surface and challenge ordinary assurnptiorls about the Black image. We feature actors all.d actresses th t go agaul.st the graill., all.d we fill you Ul. Oll. the rich history ofBlacks Ul. Arnericall. filrnrnakul.g - a history thatgoes back to 19101 And, Black Film Review is the only magazine that bringsyou news, reviews and in-deptll interviews frOtn tlle tnost vibrant tnovetnent in contelllporary film. You know about Spike Lee butwIlat about EuzIlan Palcy or lsaacJulien? Souletnayne Cisse or CIl.arles Burnette? Tllrougll out tIle African cliaspora, Black fi1rnInakers are giving us alternatives to tlle static itnages tIlat are proeluceel in Hollywood anel giving birtll to a wIlole new cinetna...be tIlere! Interview:- ----------- --- - - - - - - 4 VDL.G NO.2 by Pat Aufderheide Malian filmmaker Cheikh Oumar Sissoko discusses his latest film, Finzan, aself conscious experiment in storytelling 2 2 E e Street, NW as ing on, DC 20006 MO· BETTER BLUES 2 2 466-2753 The Music 6 o by Eugene Holley, Jr. -

The Get Right

VOL. 1 ISSUE 1 • APRIL 2020 THE GET RIGHT The Official Newsletter of F3JAX, F-L-A The mission of F3 is to plant, grow and serve small workout groups for men for the invigoration of male community leadership. The F3 Credo: Leave no man behind, but This issue: leave no man where you find him. Words from our Nantan PAGE 02 Fitness in the time of COVID Core Value of the Month PAGE 03 CSAUP CONCEPT: GROUP IS STRONGER THAN PAGE 04-05 INDIVIDUAL AO Updates PHRASE: WE LOCK SHIELDS TO PAGE 06-08 STRENGTHEN THE WHOLE, TO Value of the Q Source PROTECT THE INJURED, AND TO PAGE 09 WATCH OUR FLANKS; GUARDING AGAINST A WORLD INTENT ON JAX PAX of the Month ATTACK. PAGE 10-11 Core Value QUOTE: "UNITED WE STAND, DIVIDED PAGE 12-13 WE FALL." PATRICK HENRY The SIX Words from the Nantan BY HEISENBERG “Have you tried to perform a hard reset?” The woman at the helpless desk asked as I was informing her my iPad wouldn’t "If you fell connect to the VPN. It’s always the first suggestion they provide when you are desperate enough to call. It might apply to our current situation right now. As your down Nantan, making the call to shut down all AO’s was a most difficult decision for many reasons. First of all, I like so many yesterday, others, didn’t want to admit that this was as dire as the media portrayed. Second, I realized how much my routine would be altered. -

Programmed Moves: Race and Embodiment in Fighting and Dancing Videogames

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Programmed Moves: Race and Embodiment in Fighting and Dancing Videogames Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5pg3z8fg Author Chien, Irene Y. Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Programmed Moves: Race and Embodiment in Fighting and Dancing Videogames by Irene Yi-Jiun Chien A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Media and the Designated Emphasis in New Media in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Linda Williams, Chair Professor Kristen Whissel Professor Greg Niemeyer Professor Abigail De Kosnik Spring 2015 Abstract Programmed Moves: Race and Embodiment in Fighting and Dancing Videogames by Irene Yi-Jiun Chien Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Media Designated Emphasis in New Media University of California, Berkeley Professor Linda Williams, Chair Programmed Moves examines the intertwined history and transnational circulation of two major videogame genres, martial arts fighting games and rhythm dancing games. Fighting and dancing games both emerge from Asia, and they both foreground the body. They strip down bodily movement into elemental actions like stepping, kicking, leaping, and tapping, and make these the form and content of the game. I argue that fighting and dancing games point to a key dynamic in videogame play: the programming of the body into the algorithmic logic of the game, a logic that increasingly organizes the informatic structure of everyday work and leisure in a globally interconnected information economy. -

The Black Atlantic As a Counterculture of Modernity

1 The Black Atlantic as a Counterculture of Modernity We who are bomeless,-Among Europeans today there is no lack of those who are entitled to call themselves homeless in a distinctive and honourable sense .. We children of the future, how could we be at bome in this today~ We feel disfavour for all ideals that might lead one to feel at home even in this fragile, broken time of transition; as fur "'realities," we do not believe that they will last. The ice that still supports people today has become very thin; the wind that brings the thaw is blowing; we ourselves who are homeless constitute a force that breaks open ice and other aU too thin "realities." NietssdIe On the notion of modernity. It is a vexed question. Is not every era "'modern" in relation to the preceding one? It seems that at least one of the components of "our" modernity is the spread of the awareness we have ofit. The awareness of our awareness (the double, the second degree) is our source of strength and our torment. BIW_nl GlissRnt STRIVING TO BE both European and black requires some specific forms of double consciousness. By saying this I do not mean to suggest that taking on either or both of these unfinished identities necessarily ex hausts the subjective resources of any parti.cuIar individual. However, where racist, nationalist, or ethnically absolutist discourses orchestrate po litical relationships so that these identities appear to be mutually exclusive, occupying the space: between them or trying to demonstrate their continu ity has been viewed as a provocative and even oppositional act of political insubordination. -

Spectacle, Masculinity, and Music in Blaxploitation Cinema

Spectacle, Masculinity, and Music in Blaxploitation Cinema Author Howell, Amanda Published 2005 Journal Title Screening the Past Copyright Statement © The Author(s) 2005. The attached file is posted here with permission of the copyright owner for your personal use only. No further distribution permitted. Please refer to the journal's website for access to the definitive, published version. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/4130 Link to published version http://www.latrobe.edu.au/screeningthepast/ Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au Spectacle, masculinity, and music in blaxploitation cinema Spectacle, masculinity, and music in blaxploitation cinema Amanda Howell "Blaxploitation" was a brief cycle of action films made specifically for black audiences in both the mainstream and independent sectors of the U.S. film industry during the early 1970s. Offering overblown fantasies of black power and heroism filmed on the sites of race rebellions of the late 1960s, blaxploitation films were objects of fierce debate among social leaders and commentators for the image of blackness they projected, in both its aesthetic character and its social and political utility. After some time spent as the "bad object" of African-American cinema history,[1] critical and theoretical interest in blaxploitation resurfaced in the 1990s, in part due to the way that its images-- and sounds--recirculated in contemporary film and music cultures. Since the early 1990s, a new generation of African-American filmmakers has focused -

A Light in Darkness, Oscar Micheaux: Entrepreneur Intellectual Agitator Airic Hughes University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 7-2015 A Light in Darkness, Oscar Micheaux: Entrepreneur Intellectual Agitator Airic Hughes University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, African History Commons, American Film Studies Commons, and the American Literature Commons Recommended Citation Hughes, Airic, "A Light in Darkness, Oscar Micheaux: Entrepreneur Intellectual Agitator" (2015). Theses and Dissertations. 1317. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/1317 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. A Light in Darkness, Oscar Micheaux: Entrepreneur Intellectual Agitator A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History By Airic Hughes University of Arkansas Bachelor of Arts in History and African and African American Studies, 2011 July 2015 University of Arkansas This thesis is approved for recommendation to the Graduate Council. __________________ Dr. Calvin White Thesis Director __________________ __________________ Dr. Pearl Ford Dowe Dr. James Gigantino Committee Member Committee Member Abstract: Oscar Micheaux was a luminary who served as an agent of racial uplift, with a unique message to share with the world on behalf of the culturally marginalized African Americans. He produced projects that conveyed the complexity of the true black experience with passion and creative courage. His films empowered black audiences and challenged conventional stereotypes of black culture and potential. -

Dolemite Is My Name

DOLEMITE IS MY NAME Written by Scott Alexander and Larry Karaszewski FINAL IN THE BLACK We hear Marvin Gaye's "What's Goin' On" playing softly. VOICE I ain't lying. People love me. INT. DOLPHIN'S - DAY CU of a beat-up record from the 1950s. On the paper cover is a VERY YOUNG Rudy, in a tuxedo. It says "Rudy Moore - BUGGY RIDE" RUDY You play this, folks gonna start hoppin' and squirmin', just like back in the day. A hand lifts the record up to the face of RUDY RAY MOORE, late '40s, black, sweet, determined. RUDY When I sang this on stage, I swear to God, people fainted! Ambulance man was picking them off the floor! When I had a gig, the promoter would warn the hospital: "Rudy's on tonight -- you're gonna be carrying bodies out of the motherfucking club!" We see that we are in a RADIO BOOTH. A sign blinks "On The Air." The DJ, ROJ, frowns at the record. ROJ "Buggy Ride"? RUDY Wasn't no small-time shit. ROJ GodDAMN, Rudy! That record's 1000 years old! I've got Marvin Gaye singin' "Let's Get It On"! I can't be playin' no "Buggy Ride." (beat) Look, I have 60 seconds. I have to cue the next tune. Hm! Rudy bites his lip and walks away. Roj tries to go back to his job. He reaches for a Sly Stone single -- when Rudy suddenly bounds back up. RUDY How about "Step It Up and Go"? That's a real catchy rhythm-and-blues number.