UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

DEPICTIONS of CHASTITY: VIRTUE MADE VISIBLE Susan L'engle In

DEPICTIONS OF CHASTITY: VIRTUE MADE VISIBLE Susan L’Engle In 1969 a daughter was born to Cher and Sonny Bono. They named her Chastity, an uncommon and burdensome name for a child to bear in this time and place. The negative resonance of this name still prevails, clearly articulated in a 1996 interview with Chastity Bono, where the reporter commented: “When she was born in 1969, Chastity Bono got stuck with that name forever. ‘Not that many people call me Chastity anyway,’ she says. She prefers Chas. Hell, wouldn’t you?”1 Today in the twenty-fi rst century we all have personal takes on the meaning of the word chastity and its relevance to our individual lives, shaped by our upbringing and education and supplemented by input from various media. In the Middle Ages, however, chastity was an all- pervading and multivalent concept that regulated the lives of lay men and women, and clergy alike. The ideals of chastity were expressed verbally by churchmen, theologians, philosophers, poets, and heads of family—and recorded in sermons, Saints’ Lives, advice manuals for rulers, courtesy books, and poems of courtly romance. For many of these texts, artists created images and compositions to illustrate and reinforce the verbal discourse, and it is these visual manifestations that will be analyzed and discussed in this project. As a medievalist I am interested in the various ramifi cations of chas- tity within the strata of medieval society; as an art historian, I want to explore how the notion of chastity can be represented visually, and what circumstances provoke its illustration. -

Colbert Super PAC - 1

Colbert Super PAC - 1 Stephen Colbert’s Civics Lesson: How Colbert Super PAC Taught Viewers about Campaign Finance By Bruce W. Hardy Jeffrey A. Gottfried Kenneth M. Winneg & Kathleen Hall Jamieson Colbert Super PAC - 2 Stephen Colbert’s Civics Lesson: How Colbert Super PAC Taught Viewers about Campaign Finance Abstract This study tests whether exposure to The Colbert Report influenced knowledge of super PACs and 501(c)(4) groups, and ascertains how having such knowledge influenced viewers’ perceptions about the role of money in politics. Our analysis of a national random sample of adults interviewed after the 2012 presidential election found that viewing The Colbert Report both increased peoples’ perception of how knowledgeable they were about super PACs and 501(c)(4) groups and increased actual knowledge of campaign finance regulation regarding these independent expenditure groups. Findings suggest that the political satirist was more successful in informing his viewers about super PACs and 501(c)(4) groups than were other types of news media. Viewing The Colbert Report also indirectly influenced how useful his audience perceived money to be in politics. Colbert Super PAC - 3 Stephen Colbert’s Civics Lesson: How Colbert Super PAC Taught Viewers about Campaign Finance After faux-right-wing satirist Stephen Colbert signed control of his super PAC “Americans for a Better Tomorrow, Tomorrow” over to his Comedy Central colleague and Daily Show host Jon Stewart and, in the process, renamed it “The Definitely Not Coordinating with Stephen Colbert Super PAC,” the comic announced his candidacy for “President of the United States of South Carolina.” Some scholars characterized these moments of Colbert’s direct engagement with post-Citizens United campaign finance laws as “commentary that is entertaining and ironic, yet also critically serious” (Jones, Baym, & Day, 2012, p. -

Before the Forties

Before The Forties director title genre year major cast USA Browning, Tod Freaks HORROR 1932 Wallace Ford Capra, Frank Lady for a day DRAMA 1933 May Robson, Warren William Capra, Frank Mr. Smith Goes to Washington DRAMA 1939 James Stewart Chaplin, Charlie Modern Times (the tramp) COMEDY 1936 Charlie Chaplin Chaplin, Charlie City Lights (the tramp) DRAMA 1931 Charlie Chaplin Chaplin, Charlie Gold Rush( the tramp ) COMEDY 1925 Charlie Chaplin Dwann, Alan Heidi FAMILY 1937 Shirley Temple Fleming, Victor The Wizard of Oz MUSICAL 1939 Judy Garland Fleming, Victor Gone With the Wind EPIC 1939 Clark Gable, Vivien Leigh Ford, John Stagecoach WESTERN 1939 John Wayne Griffith, D.W. Intolerance DRAMA 1916 Mae Marsh Griffith, D.W. Birth of a Nation DRAMA 1915 Lillian Gish Hathaway, Henry Peter Ibbetson DRAMA 1935 Gary Cooper Hawks, Howard Bringing Up Baby COMEDY 1938 Katharine Hepburn, Cary Grant Lloyd, Frank Mutiny on the Bounty ADVENTURE 1935 Charles Laughton, Clark Gable Lubitsch, Ernst Ninotchka COMEDY 1935 Greta Garbo, Melvin Douglas Mamoulian, Rouben Queen Christina HISTORICAL DRAMA 1933 Greta Garbo, John Gilbert McCarey, Leo Duck Soup COMEDY 1939 Marx Brothers Newmeyer, Fred Safety Last COMEDY 1923 Buster Keaton Shoedsack, Ernest The Most Dangerous Game ADVENTURE 1933 Leslie Banks, Fay Wray Shoedsack, Ernest King Kong ADVENTURE 1933 Fay Wray Stahl, John M. Imitation of Life DRAMA 1933 Claudette Colbert, Warren Williams Van Dyke, W.S. Tarzan, the Ape Man ADVENTURE 1923 Johnny Weissmuller, Maureen O'Sullivan Wood, Sam A Night at the Opera COMEDY -

The Inventory of the Joan Fontaine Collection #570

The Inventory of the Joan Fontaine Collection #570 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center TABLE OF CONTENTS Film and Video 1 Audio 3 Printed Material 5 Professional Material 10 Correspondence 13 Financial Material 50 Manuscripts 50 Photographs 51 Personal Memorabilia 65 Scrapbooks 67 Fontaine, Joan #570 Box 1 No Folder I. Film and Video. A. Video cassettes, all VHS format except where noted. In date order. 1. "No More Ladies," 1935; "Tell Me the Truth" [1 tape]. 2. "No More Ladies," 1935; "The Man Who Found Himself," 1937; "Maid's Night Out," 1938; "The Selznick Years," 1969 [1 tape]. 3. "Music for Madam," 1937; "Sky Giant," 1938; "Maid's Night Out," 1938 [1 tape]. 4. "Quality Street," 1937. 5. "A Damsel in Distress," 1937, 2 copies. 6. "The Man Who Found Himself," 1937. 7. "Maid's Night Out," 1938. 8. "The Duke ofWestpoint," 1938. 9. "Gunga Din," 1939, 2 copies. 10. "The Women," 1939, 3 copies [4 tapes; 1 version split over two tapes.] 11. "Rebecca," 1940, 3 copies. 12. "Suspicion," 1941, 4 copies. 13. "This Above All," 1942, 2 copies. 14. "The Constant Nymph," 1943. 15. "Frenchman's Creek," 1944. 16. "Jane Eyre," 1944, 3 copies. 2 Box 1 cont'd. 17. "Ivy," 1947, 2 copies. 18. "You Gotta Stay Happy," 1948. 19. "Kiss the Blood Off of My Hands," 1948. 20. "The Emperor Waltz," 1948. 21. "September Affair," 1950, 3 copies. 22. "Born to be Bad," 1950. 23. "Ivanhoe," 1952, 2 copies. 24. "The Bigamist," 1953, 2 copies. 25. "Decameron Nights," 1952, 2 copies. 26. "Casanova's Big Night," 1954, 2 copies. -

Stephen Colbert's Super PAC and the Growing Role of Comedy in Our

STEPHEN COLBERT’S SUPER PAC AND THE GROWING ROLE OF COMEDY IN OUR POLITICAL DISCOURSE BY MELISSA CHANG, SCHOOL OF PUBLIC AFFAIRS ADVISER: CHRIS EDELSON, PROFESSOR IN THE SCHOOL OF PUBLIC AFFAIRS UNIVERSITY HONORS IN CLEG SPRING 2012 Dedicated to Professor Chris Edelson for his generous support and encouragement, and to Professor Lauren Feldman who inspired my capstone with her course on “Entertainment, Comedy, and Politics”. Thank you so, so much! 2 | C h a n g STEPHEN COLBERT’S SUPER PAC AND THE GROWING ROLE OF COMEDY IN OUR POLITICAL DISCOURSE Abstract: Comedy plays an increasingly legitimate role in the American political discourse as figures such as Stephen Colbert effectively use humor and satire to scrutinize politics and current events, and encourage the public to think more critically about how our government and leaders rule. In his response to the Supreme Court case of Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission (2010) and the rise of Super PACs, Stephen Colbert has taken the lead in critiquing changes in campaign finance. This study analyzes segments from The Colbert Report and the Colbert Super PAC, identifying his message and tactics. This paper aims to demonstrate how Colbert pushes political satire to new heights by engaging in real life campaigns, thereby offering a legitimate voice in today’s political discourse. INTRODUCTION While political satire is not new, few have mastered this art like Stephen Colbert, whose originality and influence have catapulted him to the status of a pop culture icon. Never breaking character from his zany, blustering persona, Colbert has transformed the way Americans view politics by using comedy to draw attention to important issues of the day, critiquing and unpacking these issues in a digestible way for a wide audience. -

PDF of the Princess Bride

THE PRINCESS BRIDE S. Morgenstern's Classic Tale of True Love and High Adventure The 'good parts' version abridged by WILLIAM GOLDMAN one two three four five six seven eight map For Hiram Haydn THE PRINCESS BRIDE This is my favorite book in all the world, though I have never read it. How is such a thing possible? I'll do my best to explain. As a child, I had simply no interest in books. I hated reading, I was very bad at it, and besides, how could you take the time to read when there were games that shrieked for playing? Basketball, baseball, marbles—I could never get enough. I wasn't even good at them, but give me a football and an empty playground and I could invent last-second triumphs that would bring tears to your eyes. School was torture. Miss Roginski, who was my teacher for the third through fifth grades, would have meeting after meeting with my mother. "I don't feel Billy is perhaps extending himself quite as much as he might." Or, "When we test him, Billy does really exceptionally well, considering his class standing." Or, most often, "I don't know, Mrs. Goldman; what are we going to do about Billy?" What are we going to do about Billy? That was the phrase that haunted me those first ten years. I pretended not to care, but secretly I was petrified. Everyone and everything was passing me by. I had no real friends, no single person who shared an equal interest in all games. -

'Take Zone Protest to Court'

.m.m OF 3 R >N 3343:2 BOCA RATON NEWS /ol, 15, No. 82 Wednesdoy, April 1, 1970 20 Pages 10 Cents YOUR DAY County attorneys rule out 197D APRIL 197Q rehearlngs on trailer objections S M T W T F 2 3 4 5 6 7X9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 'Take zone protest to court' ByKATHIEKEIM commissioners that because of commission decisions even though "Those are the only two cases in zoning commission Tuesday voicing Boca Raton has no other course of legislation setting up the zoning Ruff and Danciu contended it would which the board of adjustment has any objection to it. appeal on a county zoning decision commission it could not honor the have such powers. power. They are specifically not The County Zoning Commission had Census than to file a suit in circuit court, the request. "In its list of duties it is charged with empowered to deal with questions of granted a permit to Milton Greenberg county commission was advised Wolfe said that although Ruff and hearing appeals of decisions of ad- land use." to use a 635-acre tract of land west of Tuesday afternoon. Daneiu said no board of adjustment ministrative officials when it is felt The City Council has filed two Boca Raton as a trailer park, but Boca forms Earlier in the day deputy mayor had been created in spite of a they are in error — for instance, the petitions with the County Commission Raton officials and residents have Emil Danciu and city attorney John requirement that one be set up, a zoning director," Wolfe said. -

1997 Sundance Film Festival Awards Jurors

1997 SUNDANCE FILM FESTIVAL The 1997 Sundance Film Festival continued to attract crowds, international attention and an appreciative group of alumni fi lmmakers. Many of the Premiere fi lmmakers were returning directors (Errol Morris, Tom DiCillo, Victor Nunez, Gregg Araki, Kevin Smith), whose earlier, sometimes unknown, work had received a warm reception at Sundance. The Piper-Heidsieck tribute to independent vision went to actor/director Tim Robbins, and a major retrospective of the works of German New-Wave giant Rainer Werner Fassbinder was staged, with many of his original actors fl own in for forums. It was a fi tting tribute to both Fassbinder and the Festival and the ways that American independent cinema was indeed becoming international. AWARDS GRAND JURY PRIZE JURY PRIZE IN LATIN AMERICAN CINEMA Documentary—GIRLS LIKE US, directed by Jane C. Wagner and LANDSCAPES OF MEMORY (O SERTÃO DAS MEMÓRIAS), directed by José Araújo Tina DiFeliciantonio SPECIAL JURY AWARD IN LATIN AMERICAN CINEMA Dramatic—SUNDAY, directed by Jonathan Nossiter DEEP CRIMSON, directed by Arturo Ripstein AUDIENCE AWARD JURY PRIZE IN SHORT FILMMAKING Documentary—Paul Monette: THE BRINK OF SUMMER’S END, directed by MAN ABOUT TOWN, directed by Kris Isacsson Monte Bramer Dramatic—HURRICANE, directed by Morgan J. Freeman; and LOVE JONES, HONORABLE MENTIONS IN SHORT FILMMAKING directed by Theodore Witcher (shared) BIRDHOUSE, directed by Richard C. Zimmerman; and SYPHON-GUN, directed by KC Amos FILMMAKERS TROPHY Documentary—LICENSED TO KILL, directed by Arthur Dong Dramatic—IN THE COMPANY OF MEN, directed by Neil LaBute DIRECTING AWARD Documentary—ARTHUR DONG, director of Licensed To Kill Dramatic—MORGAN J. -

Click to Download

v8n4 covers.qxd 5/13/03 1:58 PM Page c1 Volume 8, Number 4 Original Music Soundtracks for Movies & Television Action Back In Bond!? pg. 18 MeetTHE Folks GUFFMAN Arrives! WIND Howls! SPINAL’s Tapped! Names Dropped! PLUS The Blue Planet GEORGE FENTON Babes & Brits ED SHEARMUR Celebrity Studded Interviews! The Way It Was Harry Shearer, Michael McKean, MARVIN HAMLISCH Annette O’Toole, Christopher Guest, Eugene Levy, Parker Posey, David L. Lander, Bob Balaban, Rob Reiner, JaneJane Lynch,Lynch, JohnJohn MichaelMichael Higgins,Higgins, 04> Catherine O’Hara, Martin Short, Steve Martin, Tom Hanks, Barbra Streisand, Diane Keaton, Anthony Newley, Woody Allen, Robert Redford, Jamie Lee Curtis, 7225274 93704 Tony Curtis, Janet Leigh, Wolfman Jack, $4.95 U.S. • $5.95 Canada JoeJoe DiMaggio,DiMaggio, OliverOliver North,North, Fawn Hall, Nick Nolte, Nastassja Kinski all mentioned inside! v8n4 covers.qxd 5/13/03 1:58 PM Page c2 On August 19th, all of Hollywood will be reading music. spotting editing composing orchestration contracting dubbing sync licensing music marketing publishing re-scoring prepping clearance music supervising musicians recording studios Summer Film & TV Music Special Issue. August 19, 2003 Music adds emotional resonance to moving pictures. And music creation is a vital part of Hollywood’s economy. Our Summer Film & TV Music Issue is the definitive guide to the music of movies and TV. It’s part 3 of our 4 part series, featuring “Who Scores Primetime,” “Calling Emmy,” upcoming fall films by distributor, director, music credits and much more. It’s the place to advertise your talent, product or service to the people who create the moving pictures. -

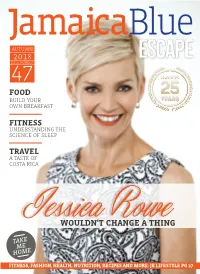

Escape Issue47 Number Food Build Your Own Breakfast

JamaicaBlue AUTUMN 2018 ESCAPE ISSUE47 NUMBER FOOD BUILD YOUR OWN BREAKFAST FITNESS UNDERSTANDING THE SCIENCE OF SLEEP TRAVEL A TASTE OF COSTA RICA JessicaRoweWOULDN'T CHANGE A THING TAKE ME HOME FITNESS, FASHION, HEALTH, NUTRITION, RECIPES AND MORE: JB LIFESTYLE PG 27 JB47-p01 Cover.indd 2 18/01/2018 23:50:49 JamaicaBlue 2018 AutumnIssue 47 FEATURES 12 COVER FEATURE p04 Jessica Rowe 14 FOOD Build your own breakfast 17 SPORT The Commonwealth Games 20 TRAVEL JAMAICA BLUE PTY LTD Beautiful Costa Rica ACN 059 236 387 22 FOOD Unit 215F1, Building 215 p14 The Entertainment Quarter A taste of chocolate p06 122 Lang Road 24 BEACON FOUNDATION Moore Park NSW 2021 PO Box 303 A pathway to success Double Bay NSW 1360 26 THE BARISTA SAYS... T 1800 622 338 Meet Jaydan Hancock of (Australia only) T 02 9302 2200 Jamaica Blue Harbour Town F 02 9302 2212 E [email protected] LIFESTYLE SECTION New Zealand Office 28 FINANCE T +64 9377 1901 Making the most of Amazon F +64 9377 1908 30 CAREER E [email protected] Pressing pause JAMAICA BLUE ESCAPE™ 32 HEALTH Editor The science of sleep Rachel Stuart 34 FITNESS Art Director The top 5 free apps Natalie Delarey p17 36 FASHION Nutrition Specialist Six great new autumn looks Sharon Natoli 40 BOOKS Welcome to the autumn Fashion Editor Autumn reads edition of Jamaica Blue Cheryl Tan 42 NUTRITION Escape. In this issue we chat Eating for good mental health to Australian TV veteran, Contributors Jessica Rowe, try our new John Burfitt 44 NUTRITION WITH Shane Conroy SHARON NATOLI 'build your own' breakfast Sarah Megginson You are when you eat menu, ready ourselves for the Gold Coast Thomas Mitchell 46 RECIPES Commonwealth Games, try on the Autumn never tasted so good latest fashions and more. -

Quest Magazine Vol 15 Issue 17

LAWTON KICKS OFF FAIR WISCONSIN’S “GO ALL THE WAY” ELECTION RALLY UW-Madison Event Start Of Statewide Campus Campaign Madison - Wisconsin lieutenant brightest unless you happen to Judge co-founded Students for a Fair Wis - governor Barbara Lawton head - be gay, lesbian, bisexual (or) consin to build student opposition to the lined a rally for UW-students transsexual,” Lawton said. 2006 ballot measure that banned gay civil here October 15 urging atten - Fair Wisconsin’s “Go All The unions marriage as well as legal recognition dees to vote in state and local Way On Election Day” addresses for all unmarried couples regardless of sexual elections and help elect candi - the fact that the state is only orientation. dates who support LGBT rights. three seats away from having a “We as students have an undeniable legacy to LGBT rights advocacy group Fair pro-fairness majority in both fight for what is right,” Judge said. “The state Wisconsin sponsored the rally as houses of the State Legislature. Legislature is the first step. It’s the spear that we part of its “Go All the Way on A high turnout, particularly need to start reversing the effects of the ban.” Election Day” campaign to en - among younger voters who tend UW-Madison College Democrats Chair Claire courage students to vote to be more supportive of LGBT Rydell also spoke at the rally, expressing her through the entire ballot, especially at the equality will be very important. concern over students who don’t consider state level. The campaign is running on col - “The only way to change the leadership in casting their ballot to be important enough to lege campuses statewide.