Self-Publishing in the Field of Australian Poetry Exegesis and Artefact

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gendered Perspectives

RESOURCE BULLETIN Winter 2014 Volume 28 :: Number 2 endered erspectives Gon InternationalP Development IN THIS ISSUE Greetings from the Center for Gender in Global Context (GenCen) at Michigan State University, the host center for the Gender, Development, and Globalization (GDG) Articles . 1 Program, formerly the Women and International Development (WID) Program! Audiovisuals . 4 The Gendered Perspectives on International Development Working Papers Seriesis Monographs and Technical pleased to announce the publication of its newest paper: Reports . 6 GPID Working Paper #303 (December 2013): Periodicals . 14 Gender, Power, and Traumatic Stress in a Q’eqchi’ Refugee Community in Mexico, by Faith R. Warner, Bloomsburg University of Pennsylvania. Books . 15 Study Opportunities . 19 This paper is available online for free at www.gencen.isp.msu.edu/ and the rest of the Working Papers Series is available at www.gencen.msu.edu/publications/ Grants and Fellowships . 21 papers.htm. Conferences . 24 As always, we encourage submissions and suggestions from our readers! We especially invite graduate students, scholars, and professionals to review one of a Calls for Papers . 26 number of books that are available for review. We also encourage submissions by authors and publishers of relevant articles and books for inclusion in future issues. Online Resources . 28 Remember, the current issue of the Resource Bulletin, along with the most recent Book Review . 30 back issues, is now online! Visit gencen.msu.edu/publications/bulletin.htm. Thank you very much, and enjoy the Winter 2014 issue of the Gendered Perspectives on International Development Resource Bulletin! Executive Editor: Anne Ferguson, PhD Managing Editor: Kristan Elwell, MPH, MA Editorial Assistants: Varsha Koduvayur **The contents of this publication were developed under a Title VI grant Michael Gendernalik from the U.S. -

Playwright's Notes

DULBINERS: A QUARTET an audio play suite by Arthur Yorinks inspired by the short stories of James Joyce NOTES FROM THE PLAYWRIGHT To acknowledge and celebrate the 100th anniversary of the publication of Dubliners, the collection of short stories by James Joyce, The Greene Space at WNYC and WQXR (with the generous support of the Sidney E. Frank Foundation) engaged me to write four audio plays based on four of the Joyce stories. Well, to declare such an assignment a “challenge” is to linger in the land of understatement. Indeed. When thinking about the work of James Joyce, one usually alights on Ulysses or Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man or Finnegan’s Wake. It’s often, too often, the novels of a writer’s oeuvre that accrues the gaze and accolades, the bride to the bride’s maids, to the neglect of their short stories. And in some respect, I was guilty of such nonsense myself. I heard the name James Joyce and simply fell into a panic, a momentary intimidation. There were good reasons, I presumed, that his work served as source material for so few films and pieces of theater. At least so few in relation to how well-known and significant Joyce’s works are; works that ushered literature into the modern era. What would I do, I thought, with the terribly long poetic passages, what would I do with work so completely “literary” in their nature (and there are such works) that they resist and repel attempts at dramatization? Well, I purchased the cheapest most unadorned paperback version of Dubliners I could find thinking that somehow if it looked like an airport novel instead of a literary tome, I would have an easier time of it. -

Spice Large.Pdf

Gernot Katzer’s Spice List (http://gernot-katzers-spice-pages.com/engl/) 1/70 (November 2015) Important notice Copyright issues This document is a byproduct of my WWW spice pages. It lists names of spices in about 100 different languages as well as the sci- This document, whether printed or in machine-readable form, may entific names used by botanists and pharmacists, and gives for each be copied and distributed without charge, provided the above no- local name the language where it is taken from and the botanical tice and my address are retained. If the file content (not the layout) name. This index does not tell you whether the plant in question is is modified, this should be indicated in the header. discussed extensively or is just treated as a side-note in the context of another spice article. Employees of Microsoft Corporation are excluded from the Another point to make perfectly clear is that although I give my above paragraph. On all employees of Microsoft Corporation, a best to present only reliable information here, I can take no warrant licence charge of US$ 50 per copy for copying or distributing this of any kind that this file, or the list as printed, or my whole WEB file in all possible forms is levied. Failure to pay this licence charge pages or anything else of my spice collection are correct, harm- is liable to juristical prosecution; please contact me personally for less, acceptable for non-adults or suitable for any specific purpose. details and mode of paying. All other usage restrictions and dis- Remember: Anything free comes without guarantee! claimers decribed here apply unchanged. -

NIKE Inc. STRATEGIC AUDIT & CORPORATE

NIKE Inc. STRATEGIC AUDIT & CORPORATE A Paper Presented as a Final Requirement in STRAMA-18 -Strategic Management Prepared by: IGAMA, ERICA Q. LAPURGA, BIANCA CAMILLE M. PIMENTEL, YVAN YOULAZ A. Presented to: PROF. MARIO BRILLANTE WESLEY C. CABOTAGE, MBA Subject Professor TABLE OF CONTENTS Page No. I. Executive Summary ……………………………………………………………………...……1 II. Introduction …………………………………………………………………………...………1 III. Company Overview ………………………………………………………………………….2 A. Company Name and Logo, Head Office, Website …………………………...……………2 B. Company Vision, Mission and Values……………………………………………….…….2 C. Objectives …………………………………………………………………………………4 D. Organizational Structure …………………………………………………….…………….4 E. Corporate Governance ……………………………………………………………….……6 1. Board of Directors …………………………………………………………….………6 2. CEO ………………………………………………………………….………….……6 3. Ownership and Control ………………………………………………….……………6 F. Corporate Resources ………………………………………………………………...……9 1. Marketing ……………………………………………………………………….….…9 2. Finance ………………………………………………………………………………10 3. Research and Development ………………………………………………….………11 4. Operations and Logistics ……………………………………………………….……13 5. Human Resources ……………………………………………………...……………14 6. Information Technology ……………………………………………………….……14 IV. Industry Analysis and Competition ...……………………………...………………………15 A. Market Share Analysis ………………………………………………………...…………15 B. Competitors’ Analysis ………………………………………………………...…………16 V. Company Situation.………… ………………………………………………………….……19 A. Financial Performance ………………………………………………………………...…19 B. Comparative Analysis……………………… -

Downloaded on 2018-08-23T18:41:03Z DHQ: Digital Humanities Quarterly: Structure Over Style: Collabor

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Cork Open Research Archive Title Structure over style: collaborative authorship and the revival of literary capitalism Author(s) Fuller, Simon; O'Sullivan, James Publication date 2017 Original citation Fuller, S. and O'Sullivan, J. (2017) 'Structure over Style: Collaborative Authorship and the Revival of Literary Capitalism', Digital Humanities Quarterly, 11 (1). http://www.digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/11/1/000286/000286.html Type of publication Article (peer-reviewed) Link to publisher's http://www.digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/11/1/000286/000286.html version Access to the full text of the published version may require a subscription. Rights © 2017 The Authors, Published by The Alliance of Digital Humanities Organizations, Affiliated with: Literary and Linguistic Computing. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/4.0/ Item downloaded http://hdl.handle.net/10468/4269 from Downloaded on 2018-08-23T18:41:03Z DHQ: Digital Humanities Quarterly: Structure over Style: Collabor... http://www.digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/11/1/000286/000286.html DHQ: Digital Humanities Quarterly Preview 2017 Volume 11 Number 1 Structure over Style: Collaborative Authorship and the Revival of Literary Capitalism Simon Fuller <simonfuller9_at_gmail_dot_com>, National University of Ireland, Maynooth James O'Sullivan <j_dot_c_dot_osullivan_at_sheffield_dot_ac_dot_uk>, University of Sheffield Abstract James Patterson is the world’s best-selling living author, but his approach to writing is heavily criticised for being too commercially driven — in many respects, he is considered the master of the airport novel, a highly-productive source of commuter fiction. -

Pantera Press Rights Guide

DISCOVER OUR BOOKS PanteraPress SUBSIDIARY RIGHTS GUIDE FRANKFURT 2016 Nurturing the Next Generation of Authors... CONTENTS Pantera Press is a young and enthusiastic Australian book publisher, passionate about growing and nurturing new talent. Founded in 2008, we pride ourselves on our innovative approach to publishing. Our Upcoming Adult Fiction ..........................4 unique business model allows us to strategically and financially invest in writing culture by nurturing and developing new, hand-picked, authors who we see as the Upcoming YA Fiction ..............................9 next generation of Australian writing talent. They are exceptional storytellers that write for a popular international audience. Backlist Adult Fiction ............................12 We released our first titles in 2010 and were short-listed in 2013 and 2014 for the Backlist Young Adult Fiction .................19 Australian Book Industry’s (ABIA) Small Publisher of the Year Award. In 2015 we were short-listed for the ABIA Innovation Award. Our team of seasoned industry professionals are fast developing a list of award winning and critically acclaimed Contact Details ......................................22 authors and titles across a range of genres. As well as publishing good stories, we aim to contribute to the wider community, hence our unique ‘good books doing good things’™ approach and the launch of the Pantera Press Foundation. Our books are distributed in Australia and New Zealand by Bloomsbury, and we hold world rights to all of our titles. We would love to introduce you to our list. 3 Upcoming Adult Fiction READ EXCERPT Upcoming WATCH PROMO Adult Fiction THE TAO DECEPTION THE NEW TORI SWYFT THRILLER John M. Green The pope is assassinated. -

Global Invasive Plants in Thailand and Its Status and a Case Study of Hydrocotyle Umbellata L

Global invasive plants in Thailand and its status and a case study of Hydrocotyle umbellata L. Siriporn Zungsontiporn Weed Science Group, Plant Protection Research and Development Office, Department of Agriculture, Bangkok, Thailand 10900 Email: [email protected] Summary Global invasive plant may invade in some countries, but it is not invasive plant in its native country or in range of distribution. Those plants are utilized in some means, such as vegetable, fruit, ornamental plant or medicinal plant in it native country or even it was invasive plant but people learned how to manage with that plant, they can utilize it. On the contrary way, an invasive plant of any country may not be invasive in any country else. Most of the invasive plants are intentionally introduced to a country for some purpose especially for ornamental plant. Hydrocotyle umbrellata L. was introduced to Thailand as ornamental plant, the plant can grow well and with some habit of invasive plant of this plant, nowadays the plant was found in many natural areas as weed. Introduction Most of invasive plant in an area is alien plant which was introduced from different habitat within a country or other country across geographic barrier. Well development of transportation stimulates traveling and international trading which cause of increasing introduction of alien species. Some of introduced alien plants can establish and spread out if it can adapt itself to survive in the new habitat well. If the environment of new habitat is suitable for it growth, the plant may express it invasiveness and compete for space and nutrient with native plant which it may complete over native plants due to lack of it natural enemy in new habitat. -

The Phenomena of Book Clubs and Literary Awards in Contemporary America

What Is America Reading?: The Phenomena of Book Clubs and Literary Awards in Contemporary America Author: Lindsay Winget Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/569 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2008 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. What Is America Reading?: The Phenomena of Book Clubs and Literary Awards in Contemporary America Lindsay Winget Advisor: Professor Judith Wilt English Department Honors Thesis Submitted April 14, 2008 CONTENTS Preface: Conversation in Books, Books in Conversation 2 Chapter One: “Go Discuss with Your Book Club…”: My Sister’s Keeper by Jodi Picoult and The Memory Keeper’s Daughter by Kim Edwards 19 Chapter Two: “And the Prize for Fiction Goes to…”: Gilead by Marilynne Robinson and Interpreter of Maladies by Jhumpa Lahiri 52 Conclusion: Literature, All on the Same Shelf 78 Works Cited 84 Acknowledgements 87 “But the act of reading, the act of seeing a story on the page as opposed to hearing it told—of translating story into specific and immutable language, putting that language down in concrete form with the aid of the arbitrary handful of characters our language offers, of then handing the story on to others in a transactional relationship—that is infinitely more complex, and stranger, too, as though millions of us had felt the need, over the span of centuries, to place messages in bottles, to ameliorate the isolation of each of us, each of us a kind of desert island made less lonely by words.” - ANNA QUINDLEN, HOW READING CHANGED MY LIFE 1 PREFACE: CONVERSATION IN BOOKS, BOOKS IN CONVERSATION Seventeen years ago, I proudly closed the cover of Hop on Pop by Dr. -

Right-Click and Save to Download

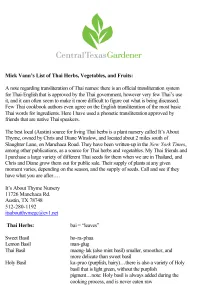

Cilantro phak chii (roots=raak phak chii; seeds=met phak chii) Rau Ram ? aka Viet. Cilantro; Polygonum odoratum Sawtooth coriander phak chii farang Spearmint sa-ra-nay the true Thai mint is called “water mint” Asian pennywort bai bua bok Vietnamese Mint phak phai (Polygonum sp.) Chilies: Prik “mouse dropping” prik khii nuu 60-80K scovilles “farm” mouse dropping prik khii nuu suan shorter, fatter, smaller seeds “dragon’s Eye “ m.d. prik khii nuu sun yaew 4cm “sky pointing” prik chi faa 6-10cm; red, grn, yellow; 35-45K scovilles banana stalk chile prik yuak 10-15cm; ylw-grn>red orange chile prik haeng 3cm, thin-fleshed, very hot, slightly sour Sweet bell pepper prik waan …there are ten main types that are commonly used…originally brought to Thailand in 1629 by the Portuguese (it took only 30 years for chiles to cover all parts of the country (which included parts of Cambodia and Laos at the time, and was much larger than Thailand’s current size) and be completely adapted into the cuisine)…previously the heat came from peppercorns (called “Prik Thai”): green (prik thai onn), black, and white (slightly different and spicier than our white peppercorns) Garlic kra-tiem Shallots hawm-lek, Red shallots hawm-daeng Green Onions ton-hawm Onion hua-hawm Lemongrass ta-krai Bay Leaf gra-wan Galangal khaa Ginger khing Cardamom luuk gra-waan Turmeric kha-min White Turmeric khamin khao Red turmeric khamin leuang Sugarcane turmeric khamin ooy, khamin chan “Chinese keys” kra-chai aka: “finger root”, “rhizome”, “wild ginger” Torch ginger ka-laa Pepper Leaf chaplu aka “wild tea leaf”, “betel leaf” Cumin Leaf yee-rah Thai Lime Leaf mak-root, ma-groot Note: the common English name, Kaffir leaf, has been changed because the word “kaffir”, which is from South Africa and means “colored” (referring to that portion of the population from India) is derogatory. -

Horse Todos a B Alliebelle 23.072 a Big To'do 26.392 a Bit

HORSE TODOS A B ALLIEBELLE 23.072 A BIG TO'DO 26.392 A BIT STORMY 25.592 A BOY NAMED EM 28.675 A BRILLIANT IDEA 31.402 A BRUSH OF BEAUTY 21.393 A CAT NAMED SNIPE 28.551 A CAT THAT FLIES 25.368 A CENTURIAN 29.172 A DEVILISH RIDE 24.916 A DIEHL 34.923 A DOS PUNTAS 42.616 A E PHI SENSATION 23.497 A FLEET OF NINE 23.302 A GIRL NAMED MARIA 29.537 A GLASS OF WATER 22.147 A GOLDEN JET 22.575 A GRAND N' MORE 19.560 A JEALOUS WOMAN 36.719 A LA MODA 28.673 A LIL DUMAANI 27.721 A LISTER 25.068 A LITTLE AT A TIME 26.233 A LITTLE OFF 31.467 A LITTLE TOO LATE 25.373 A LOT OF ACTION 26.490 A LOT OF MON 27.211 A MATTEROFSPEAKING 24.041 A MCCOUGHTRY 25.178 A MI ZORRITO 44.348 A MILLION FIELDS 25.005 A MOMENT IN TIME 29.541 A NATIONALTREASURE 33.592 A NATURAL 29.383 A NEW DAWN 25.094 A NEW YORK PHILLIE 23.229 A P MINK 29.223 A P VALOR 30.045 A PERFECT SQUEEZE 28.415 A PINT FOR MARY 26.393 A PLUS TOPPER 28.873 A QUESTION OF TIME 21.185 A RACING DELIGHT 28.495 A RANG A TANG 26.600 A ROCKY STORM 21.775 A ROD 33.263 A ROGUE SNUCK IN 24.666 A ROYAL FLUSH A 18.962 A SHE'S ADORABLE 33.925 A SHOT AWAY 28.920 A SINGLE MAN 21.532 A SMART JUDGE 23.806 A STAR IS GORN 23.954 A STORY OF REVENGE 29.442 A STUDENT 29.494 A T MONEY 30.054 A TOE BY THREE 25.800 A TOUT L'HEURE 42.875 A TRIPP ROYALE 29.433 A USED GUN 23.246 A WALK ABOVE 25.728 A WINK AND A SMILE 32.705 A WISH FOR KOSUTE 20.514 A WORD TO THE WISE 30.596 A Z WARRIOR 35.400 A'INTYOUDREAMIN 22.520 A. -

His 2008 02 Nd 02.Indd 1 3.3.2008 0:05:32 Deutsch Nepal

editorial obsah Glosář Matěj Kratochvíl 2 Barbez Karel Veselý 4 Volapük / Ovo Petr Ferenc 5 Opening Performance Orchestra Petr Ferenc 6 aktuálně Charalambides Matěj Kratochvíl 7 Vážení a milí čtenáři, Člověk jdoucí za hudebním zážitkem většinou ví, co jej čeká, co má sledovat a očekávat a jak se chovat. Že se bude hrát na harfy či laptopy, že se má tleskat po só- Zvuky v prostoru Jozef Cseres 8 lech či netleskat po větách symfonie, že zvuky se bu- dou linout z pódia a bude víceméně jasné, kdo je vydá- vá. Jsou tu prostě určité jistoty. Zajímá-li nás inspirativní Orbis pictus Petr Ferenc 12 nejistota, je pole zvukových instalací nebo sound artu dobrou volbou. Především můžeme váhat, zda jde vů- bec o hudbu, zvláště když řada tvůrců přichází z výtvar- téma Instalace Alvina Luciera Thomas Bailey 18 ného břehu. Každé jednotlivé dílo pak nabízí svou vlast- ní sadu nejistot a příležitostí k podivu: Jsou tyto zvuky Zvuk – umění – město Karel Veselý 20 elektronické, nebo akustické? Jak souvisí to, co vidím, s tím, co slyším? V takto pomezním oboru je nějaký systematický pře- Steve Roden Pavel Zelinka 22 hled ještě o chlup nemožnější než ve sférách čistě hu- debních, toto číslo tedy nabízí spíše sondy do pestrosti přístupů. Od historických mezníků, jaký představu- je třeba dílo Alvina Luciera Bird And Person Dyning, se dostaneme k autorům výstavy Orbis Pictus, kte- Gordon Monahan Jesse Stewart 25 rá v současnosti s úspěchem koluje po světě, od vy- prázdněných reproduktorů Gordona Monahana přesko- číme k telefonům Dona Rittera, zpívajícím buddhistickou Valentin Silvestrov Vítězslav Mikeš 28 mantru. -

Dancers in the Sky Stories

DANCERS IN THE SKY STORIES DANCERS IN THE SKY STORIES Barry Eysman Copyright 2011 by Barry Eysman All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted by any means— whether auditory, graphic, mechanical, or electronic—without written permission of both publisher and author, except in the case of brief excerpts used in critical articles and reviews. Unauthorized reproduction of any part of this work is illegal and is punishable by law. ISBN 978-1-257-05256-1 EVERYDAY MAGIC. IN THE MERE LIVING. WE TOO. IN LOVING MEMORY OF JASE, JOSHUA, DIEGO, ROB AND BERRITY— MY FRIENDS TABLE OF CONTENTS Before the Fall........................................................................................1 Pirouette .................................................................................................5 Late Night Radio ................................................................................... 8 Something is Really Wrong .................................................................10 My Name is David ...............................................................................13 The Brindling Day ...............................................................................17 Halloween Charade ..............................................................................19 And his Eyes be as Blue as the Sea......................................................20 Paul Finally Gets to Play Basketball ....................................................51 Doing Time in Tooth Ache Town ........................................................52