Revenge Body: a Novel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Playwright's Notes

DULBINERS: A QUARTET an audio play suite by Arthur Yorinks inspired by the short stories of James Joyce NOTES FROM THE PLAYWRIGHT To acknowledge and celebrate the 100th anniversary of the publication of Dubliners, the collection of short stories by James Joyce, The Greene Space at WNYC and WQXR (with the generous support of the Sidney E. Frank Foundation) engaged me to write four audio plays based on four of the Joyce stories. Well, to declare such an assignment a “challenge” is to linger in the land of understatement. Indeed. When thinking about the work of James Joyce, one usually alights on Ulysses or Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man or Finnegan’s Wake. It’s often, too often, the novels of a writer’s oeuvre that accrues the gaze and accolades, the bride to the bride’s maids, to the neglect of their short stories. And in some respect, I was guilty of such nonsense myself. I heard the name James Joyce and simply fell into a panic, a momentary intimidation. There were good reasons, I presumed, that his work served as source material for so few films and pieces of theater. At least so few in relation to how well-known and significant Joyce’s works are; works that ushered literature into the modern era. What would I do, I thought, with the terribly long poetic passages, what would I do with work so completely “literary” in their nature (and there are such works) that they resist and repel attempts at dramatization? Well, I purchased the cheapest most unadorned paperback version of Dubliners I could find thinking that somehow if it looked like an airport novel instead of a literary tome, I would have an easier time of it. -

Downloaded on 2018-08-23T18:41:03Z DHQ: Digital Humanities Quarterly: Structure Over Style: Collabor

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Cork Open Research Archive Title Structure over style: collaborative authorship and the revival of literary capitalism Author(s) Fuller, Simon; O'Sullivan, James Publication date 2017 Original citation Fuller, S. and O'Sullivan, J. (2017) 'Structure over Style: Collaborative Authorship and the Revival of Literary Capitalism', Digital Humanities Quarterly, 11 (1). http://www.digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/11/1/000286/000286.html Type of publication Article (peer-reviewed) Link to publisher's http://www.digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/11/1/000286/000286.html version Access to the full text of the published version may require a subscription. Rights © 2017 The Authors, Published by The Alliance of Digital Humanities Organizations, Affiliated with: Literary and Linguistic Computing. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/4.0/ Item downloaded http://hdl.handle.net/10468/4269 from Downloaded on 2018-08-23T18:41:03Z DHQ: Digital Humanities Quarterly: Structure over Style: Collabor... http://www.digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/11/1/000286/000286.html DHQ: Digital Humanities Quarterly Preview 2017 Volume 11 Number 1 Structure over Style: Collaborative Authorship and the Revival of Literary Capitalism Simon Fuller <simonfuller9_at_gmail_dot_com>, National University of Ireland, Maynooth James O'Sullivan <j_dot_c_dot_osullivan_at_sheffield_dot_ac_dot_uk>, University of Sheffield Abstract James Patterson is the world’s best-selling living author, but his approach to writing is heavily criticised for being too commercially driven — in many respects, he is considered the master of the airport novel, a highly-productive source of commuter fiction. -

The Future of Reputation: Gossip, Rumor, and Privacy on the Internet

GW Law Faculty Publications & Other Works Faculty Scholarship 2007 The Future of Reputation: Gossip, Rumor, and Privacy on the Internet Daniel J. Solove George Washington University Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.gwu.edu/faculty_publications Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Solove, Daniel J., The Future of Reputation: Gossip, Rumor, and Privacy on the Internet (October 24, 2007). The Future of Reputation: Gossip, Rumor, and Privacy on the Internet, Yale University Press (2007); GWU Law School Public Law Research Paper 2017-4; GWU Legal Studies Research Paper 2017-4. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2899125 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in GW Law Faculty Publications & Other Works by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/ abstract=2899125 The Future of Reputation Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/ abstract=2899125 This page intentionally left blank Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/ abstract=2899125 The Future of Reputation Gossip, Rumor, and Privacy on the Internet Daniel J. Solove Yale University Press New Haven and London To Papa Nat A Caravan book. For more information, visit www.caravanbooks.org Copyright © 2007 by Daniel J. Solove. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. -

Pantera Press Rights Guide

DISCOVER OUR BOOKS PanteraPress SUBSIDIARY RIGHTS GUIDE FRANKFURT 2016 Nurturing the Next Generation of Authors... CONTENTS Pantera Press is a young and enthusiastic Australian book publisher, passionate about growing and nurturing new talent. Founded in 2008, we pride ourselves on our innovative approach to publishing. Our Upcoming Adult Fiction ..........................4 unique business model allows us to strategically and financially invest in writing culture by nurturing and developing new, hand-picked, authors who we see as the Upcoming YA Fiction ..............................9 next generation of Australian writing talent. They are exceptional storytellers that write for a popular international audience. Backlist Adult Fiction ............................12 We released our first titles in 2010 and were short-listed in 2013 and 2014 for the Backlist Young Adult Fiction .................19 Australian Book Industry’s (ABIA) Small Publisher of the Year Award. In 2015 we were short-listed for the ABIA Innovation Award. Our team of seasoned industry professionals are fast developing a list of award winning and critically acclaimed Contact Details ......................................22 authors and titles across a range of genres. As well as publishing good stories, we aim to contribute to the wider community, hence our unique ‘good books doing good things’™ approach and the launch of the Pantera Press Foundation. Our books are distributed in Australia and New Zealand by Bloomsbury, and we hold world rights to all of our titles. We would love to introduce you to our list. 3 Upcoming Adult Fiction READ EXCERPT Upcoming WATCH PROMO Adult Fiction THE TAO DECEPTION THE NEW TORI SWYFT THRILLER John M. Green The pope is assassinated. -

Tube the “New”

A PARENTS TELEVISION COUNCIL * SPECIAL REPORT * DECEMBER 17, 2008 The “New” Tube A Content Analysis of YouTube -- the Most Popular Online Video Destination PARENTS TELEVISION COUNCIL ™ L. Brent Bozell III Founder TABLE OF CONTENTS Tim Winter President Mark Barnes Executive Summary 1 Senior Consultant Background 3 Melissa Henson Director of Communications Study Parameters and Methodology 3 and Public Education Casey Bohannan Overview of Major Findings 6 Internet Communications Manager Results 8 Christopher Gildemeister Senior Writer/Editor Text Commentary 8 Michelle Jackson-McCoy, Ph.D. Director of Research Examples 9 Aubree Bowling Senior Entertainment Analyst Video Titles 11 Greg Rock Video Content 12 Ally Matteodo Amanda Pownall Sex 12 Justin Capers Oliver Saria Language 14 Entertainment Analysts Dan Isett Violence 15 Director of Public Policy Conclusion 16 Gavin Mc Kiernan National Grassroots Director Reference 17 Kevin Granich Assistant to the Grassroots Director Appendix 18 Glen Erickson Director of Corporate Relations About the PTC 19 LaQuita Marshall Assistant to the Director of Corporate Relations Patrick Salazar Vice President of Development Marty Waddell Senior Development Officer FOR MEDIA INQUIRIES Larry Irvin Nancy Meyer PLEASE CONTACT Development Officers Kelly Oliver or Megan Franko Tracy Ferrell CRC Public Relations Development Coordinator (703) 683-5004 Brad Tweten Chief Financial Officer Jane Dean Office and Graphics Administrator PTC’S HOLLYWOOD HEADQUARTERS 707 Wilshire Boulevard, Suite 2075 Los Angeles, CA 90017 • (213) 629-9255 www.ParentsTV.org® ® The PTC is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit research and education foundation. www.ParentsTV.org ® © Copyright 2008 – Parents Television Council 2 The “New” Tube A Content Analysis of YouTube – the Most Popular Online Video Destination EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Children are consuming more and more of their video entertainment outside the traditional confines of a television set. -

New York ABAA Book Fair 2017

Lux Mentis, Booksellers 110 Marginal Way #777 Portland, ME 04101 Member: ILAB/ABAA T. 207.329.1469 [email protected] www.luxmentis.com New York ABAA Book Fair 2017 1. Abiel, Dante. Necromantic Sorcery: The Forbidden Rites Of Death Magick. Presented by E.A. Koetting. Become a Living God, 2014. First Edition. Minimal shelf/edge wear, else tight, bright, and unmarred. Black velvet boards, silver gilt lettering and decorative elements, black endpages. 8vo. 279pp. Illus. (b/w plates). Glossary. Limited edition of 300. Near Fine. No DJ, as Issued. Hardcover. (#9093) $750.00 The 'fine velvet edition" (there was a smaller edition bound in leather). "Necromantic Sorcery is the FIRST grimoire to ever expose the most evil mysteries of death magick from the Western, Haitian Vodoun, and Afrikan Kongo root currents. In it, you are going to learn the most extreme rituals for shamelessly exploiting the magick of the dead, and experiencing the damnation of Demonic Descent on the Left Hand Path." (from the publisher) A provokative approach to Saturnian Necromancy. Rather scarce in the market. 2. Adams, Evelyn. Hollywood Discipline: A Bizarre Tale of Lust and Passion. New York: C-L Press, 1959. Limited Edition. Minor shelf/edge wear, minor discoloration to newsprint, else tight, bright, and unmarred. Color pictorial wraps with artwork of illustrious BDSM artist Gene Bilbrew, also known as “Eneg.” 8vo. 112pp. Illus. (b/w plates). Very Good in Wraps. Original Wraps. (#9086) $150.00 Limited illustrated first edition paperback, Inside cover black and white illustration art also by Bilbrew. Unusual in the slew of BDSM publications to come out in the 1950s and 1960s Irving Klaw era of bondage pulps. -

The Phenomena of Book Clubs and Literary Awards in Contemporary America

What Is America Reading?: The Phenomena of Book Clubs and Literary Awards in Contemporary America Author: Lindsay Winget Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/569 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2008 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. What Is America Reading?: The Phenomena of Book Clubs and Literary Awards in Contemporary America Lindsay Winget Advisor: Professor Judith Wilt English Department Honors Thesis Submitted April 14, 2008 CONTENTS Preface: Conversation in Books, Books in Conversation 2 Chapter One: “Go Discuss with Your Book Club…”: My Sister’s Keeper by Jodi Picoult and The Memory Keeper’s Daughter by Kim Edwards 19 Chapter Two: “And the Prize for Fiction Goes to…”: Gilead by Marilynne Robinson and Interpreter of Maladies by Jhumpa Lahiri 52 Conclusion: Literature, All on the Same Shelf 78 Works Cited 84 Acknowledgements 87 “But the act of reading, the act of seeing a story on the page as opposed to hearing it told—of translating story into specific and immutable language, putting that language down in concrete form with the aid of the arbitrary handful of characters our language offers, of then handing the story on to others in a transactional relationship—that is infinitely more complex, and stranger, too, as though millions of us had felt the need, over the span of centuries, to place messages in bottles, to ameliorate the isolation of each of us, each of us a kind of desert island made less lonely by words.” - ANNA QUINDLEN, HOW READING CHANGED MY LIFE 1 PREFACE: CONVERSATION IN BOOKS, BOOKS IN CONVERSATION Seventeen years ago, I proudly closed the cover of Hop on Pop by Dr. -

Die Coca-Cola-Blacklist: Dies Darf Nicht Auf Coca-Cola-Flaschen Geschrieben Werden 1

Die Coca-Cola-Blacklist: Dies darf nicht auf Coca-Cola-Flaschen geschrieben werden 1 „Group 0“: µ barthoisgay boner chink abart bartke boning chowbox abfall battlefield boob chubby abfluss bbw boody cialis abfluß bdolfbitler booger circlejerk abort beast booty climax abschaum beatthe bordell clit abscheu beefcattle bourbon cloake abwasser behindies brackwasser closetqueen abwichs bellywhacker brainfuk clubcola adult berber brainjuicer clubmate aersche bestial bratze cocaln affe biatch brauchwasser cock affegsicht biatsch breasts cocks afri bigboobs brecheisen coitus after bigfat brechmittel cojones ahole bigtits bremsspur cokaine ahrschloch bigtitts browntown cokamurat aktmodel binde brueste cokmuncher altepute bionade brust coksucka amaretto bitch brutal coprophagie anahl blacklist buceta copulation anai blackwallstreet buffoon cornhole anarchi blaehen bugger covered anarl blaehung buggery cox angerfist blaeser bukkake cptmorgan animal blähung bull crap anthrax blasehase bulldager crapper antidfb blasen bullen cretin antrax blasmaeuler bullshit crossdresser apecrime blasmaul bumbandit crossdressing areschloch blechschlüpfer bumhole cuckold arsch bleichmittel bumse cum arsebandit blockhead bunghole cumm arzchloch blödfrau busen cumshot asbach blödk bushboogie cunilingus aschevonoma blödmann butt cunillingus ausfluss blödvolk buttface cunnilingus ausfluß bloody butthole cunt ausscheidung blowjob buttmuch cuntlick auswurf blowjob buttpirate cunts autobahn blowyourwad buttplug cyberfuc ayir bluemovie butts dalailama azzlicka blumkin cacker -

'Just the Women'*

‘Just the Women’* An evaluation of eleven British national newspapers’ portrayal of women over a two week period in September 2012, including recommendations on press regulation reform in order to reduce harm to, and discrimination against, women A joint report by: Eaves End Violence Against Women Coalition Equality Now OBJECT November 2012 * ‘just the women’ is what Newsnight editor Peter Rippon reportedly wrote in an email to a colleague concerning the lack of other authorities for evidence of Jimmy Savile’s abuse 1 Contents: Introduction and Executive Summary 3 ‘Now that’s an invasion of her privates’: Rape culture and the reporting of violence against women and girls 9 ‘Brit tot parade!’: The reporting of abuse of girls, and the sexualisation of girls in newspapers 15 ‘Irina is a booty’: The objectification and sexualisation of women and the mainstreaming of the sex industries in newspapers 20 ‘Babes, retro babes, celeb babes, sports babes, hot celeb babe pics’: Disappearing, stereotyping and humiliating women 26 Conclusions and Recommendations 31 2 INTRODUCTION The Leveson Inquiry was announced in July 2011 after months of allegations and revelations about press conduct. Although perhaps focused on phone hacking and relationships between the media, the police and politicians, the Inquiry’s actual terms of reference are broad1. They include: “To inquire into the culture, practices, and ethics of the press…: “To make recommendations: “For a new more effective policy and regulatory regime which supports the integrity and freedom of -

Personal Music Collection

Christopher Lee :: Personal Music Collection electricshockmusic.com :: Saturday, 25 September 2021 < Back Forward > Christopher Lee's Personal Music Collection | # | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | | DVD Audio | DVD Video | COMPACT DISCS Artist Title Year Label Notes # Digitally 10CC 10cc 1973, 2007 ZT's/Cherry Red Remastered UK import 4-CD Boxed Set 10CC Before During After: The Story Of 10cc 2017 UMC Netherlands import 10CC I'm Not In Love: The Essential 10cc 2016 Spectrum UK import Digitally 10CC The Original Soundtrack 1975, 1997 Mercury Remastered UK import Digitally Remastered 10CC The Very Best Of 10cc 1997 Mercury Australian import 80's Symphonic 2018 Rhino THE 1975 A Brief Inquiry Into Online Relationships 2018 Dirty Hit/Polydor UK import I Like It When You Sleep, For You Are So Beautiful THE 1975 2016 Dirty Hit/Interscope Yet So Unaware Of It THE 1975 Notes On A Conditional Form 2020 Dirty Hit/Interscope THE 1975 The 1975 2013 Dirty Hit/Polydor UK import {Return to Top} A A-HA 25 2010 Warner Bros./Rhino UK import A-HA Analogue 2005 Polydor Thailand import Deluxe Fanbox Edition A-HA Cast In Steel 2015 We Love Music/Polydor Boxed Set German import A-HA East Of The Sun West Of The Moon 1990 Warner Bros. German import Digitally Remastered A-HA East Of The Sun West Of The Moon 1990, 2015 Warner Bros./Rhino 2-CD/1-DVD Edition UK import 2-CD/1-DVD Ending On A High Note: The Final Concert Live At A-HA 2011 Universal Music Deluxe Edition Oslo Spektrum German import A-HA Foot Of The Mountain 2009 Universal Music German import A-HA Hunting High And Low 1985 Reprise Digitally Remastered A-HA Hunting High And Low 1985, 2010 Warner Bros./Rhino 2-CD Edition UK import Digitally Remastered Hunting High And Low: 30th Anniversary Deluxe A-HA 1985, 2015 Warner Bros./Rhino 4-CD/1-DVD Edition Boxed Set German import A-HA Lifelines 2002 WEA German import Digitally Remastered A-HA Lifelines 2002, 2019 Warner Bros./Rhino 2-CD Edition UK import A-HA Memorial Beach 1993 Warner Bros. -

UCC Library and UCC Researchers Have Made This Item Openly Available

UCC Library and UCC researchers have made this item openly available. Please let us know how this has helped you. Thanks! Title Structure over style: collaborative authorship and the revival of literary capitalism Author(s) Fuller, Simon; O'Sullivan, James Publication date 2017 Original citation Fuller, S. and O'Sullivan, J. (2017) 'Structure over Style: Collaborative Authorship and the Revival of Literary Capitalism', Digital Humanities Quarterly, 11 (1). http://www.digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/11/1/000286/000286.html Type of publication Article (peer-reviewed) Link to publisher's http://www.digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/11/1/000286/000286.html version Access to the full text of the published version may require a subscription. Rights © 2017 The Authors, Published by The Alliance of Digital Humanities Organizations, Affiliated with: Literary and Linguistic Computing. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/4.0/ Item downloaded http://hdl.handle.net/10468/4269 from Downloaded on 2021-09-26T12:44:35Z DHQ: Digital Humanities Quarterly: Structure over Style: Collabor... http://www.digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/11/1/000286/000286.html DHQ: Digital Humanities Quarterly Preview 2017 Volume 11 Number 1 Structure over Style: Collaborative Authorship and the Revival of Literary Capitalism Simon Fuller <simonfuller9_at_gmail_dot_com>, National University of Ireland, Maynooth James O'Sullivan <j_dot_c_dot_osullivan_at_sheffield_dot_ac_dot_uk>, University of Sheffield Abstract James Patterson is the world’s best-selling living author, but his approach to writing is heavily criticised for being too commercially driven — in many respects, he is considered the master of the airport novel, a highly-productive source of commuter fiction. -

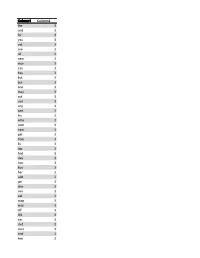

Column2 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3

Column1 Column2 the 3 and 3 for 3 you 3 not 3 are 3 all 3 new 3 was 3 can 3 has 3 but 3 our 3 one 3 may 3 out 3 use 3 any 3 see 3 his 3 who 3 web 3 now 3 get 3 how 3 its 3 top 3 had 3 day 3 two 3 buy 3 her 3 add 3 jan 3 she 3 sex 3 set 3 map 3 way 3 off 3 did 3 car 3 dvd 3 own 3 end 3 him 3 per 3 big 3 law 3 art 3 usa 3 old 3 non 3 why 3 low 3 man 3 job 3 too 3 men 3 box 3 gay 3 air 3 yes 3 hot 3 say 3 dec 3 san 3 tax 3 got 3 let 3 act 3 red 3 key 3 few 3 age 3 oct 3 pay 3 war 3 nov 3 fax 3 yet 3 sun 3 rss 3 run 3 net 3 put 3 try 3 god 3 log 3 faq 3 fun 3 feb 3 sep 3 lot 3 ask 3 due 3 mar 3 pro 3 url 3 aug 3 ago 3 apr 3 via 3 bad 3 far 3 jul 3 jun 3 oil 3 bit 3 bay 3 bar 3 dog 3 eur 3 pdf 3 usr 3 mon 3 com 3 gas 3 six 3 pre 3 sat 3 zip 3 bid 3 fri 3 wed 3 inn 3 ltd 3 los 3 inc 3 win 3 bed 3 tue 3 ass 3 thu 3 sea 3 cut 3 tel 3 kit 3 boy 3 est 3 son 3 mac 3 iii 3 gmt 3 max 3 xml 3 bin 3 van 3 ads 3 pop 3 int 3 hit 3 eye 3 usb 3 php 3 etc 3 msn 3 fee 3 las 3 min 3 aid 3 fat 3 saw 3 pst 3 xxx 3 tom 3 sub 3 led 3 fan 3 ten 3 cat 3 die 3 pet 3 guy 3 dev 3 cup 3 vol 3 lee 3 bob 3 fit 3 met 3 www 3 cum 3 ice 3 llc 3 sec 3 bus 3 bag 3 ibm 3 nor 3 bug 3 mid 3 jim 3 del 3 joe 3 cds 3 lab 3 cvs 3 des 3 lcd 3 ave 3 pic 3 tag 3 mix 3 vhs 3 fix 3 ray 3 dry 3 spa 3 con 3 ups 3 var 3 won 3 doc 3 mom 3 row 3 usd 3 eat 3 aim 3 les 3 ann 3 tip 3 ski 3 dan 3 fly 3 hey 3 bbc 3 tea 3 avg 3 sky 3 rom 3 toy 3 src 3 hip 3 dot 3 hiv 3 pda 3 dsl 3 zum 3 dna 3 tim 3 sql 3 don 3 gps 3 acc 3 cap 3 ink 3 pin 3 raw 3 gnu 3 ben 3 aol 3 hat 3 lib 3 utc 3 der 3 cam 3 wet