The Influence of Message Structure, Political Ideology and Time on Audience

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

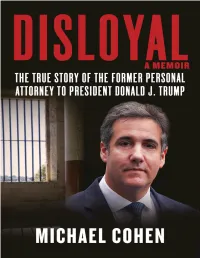

2020 Michael Cohen

Copyright © 2020 by Michael Cohen All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018. Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or [email protected]. Skyhorse® and Skyhorse Publishing® are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc.®, a Delaware corporation. Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file. ISBN: 978-1-5107-6469-9 eBook: 978-1-5107-6470-5 Cover design by Brian Peterson Cover photographs by Getty Images All interior photos © 2020 Michael Cohen Printed in the United States of America Dedication I dedicate this book to the love of my life, my wife Laura, and to my wonderful children, Samantha and Jake. The three of you endured so much during my years with Donald Trump and in the years since then. You have been subjected to harassment, insults and threats; you have seen me get arrested and charged and put in prison (twice). But the deepest suffering must have come as you watched me play an active role in the despicable acts of Mr. -

1 - Centre Stage and Our Debate Underway

Munk Debate on the US Election September 30, 2016 Rudyard Griffiths: This is the heart of downtown Toronto, a city that is home to more than six million people, the skyline carved in the waters of Lake Ontario and here we are, everyone, at Roy Thomson Hall. Its distinctive exterior design, we know it well, reflective by day, transparent by night. This is Toronto’s premier concert hall. It’s a venue usually for the biggest names in entertainment, but tonight before 3,000 people the latest in a series of Munk Debates, a clash of ideas over the US presidential election. Good evening, my name is Rudyard Griffiths and it is once again my pleasure to be your moderator tonight for this debate, this important debate. I want to start by welcoming the North American wide television audience tuning in right now C-SPAN across the continental US and here in Canada coast to coast on CPAC. A warm hello also to the online audience watching right now; Facebook Live streaming this debate over facebook.com, our social media partner, on the websites of our digital and print partner theglobeandmail.com and, of course, on our own website themunkdebates.com and a hello to all of you, the 3,000 people who have once again filled Roy Thomson Hall to capacity. Bravo. Our ability year in and year out, debate in and debate out to bring to you some of the world’s best debaters, some of the brightest minds, the sharpest thinkers to weigh in on the big global challenges, issues and problems facing the world would not be possible without the generosity, the foresight and the commitment of our host tonight. -

Geesin Mollan Trump and Trumpism FINAL

University of Dundee Donald Trump and Trumpism Mollan, Simon; Geesin, Beverly Published in: Organization DOI: 10.1177/1350508419870901 Publication date: 2020 Document Version Peer reviewed version Link to publication in Discovery Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Mollan, S., & Geesin, B. (2020). Donald Trump and Trumpism: Leadership, ideology and narrative of the business executive turned politician. Organization, 27(3), 405-418. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508419870901 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in Discovery Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from Discovery Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain. • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 26. Sep. 2021 Donald Trump and Trumpism: leadership, ideology and narrative of the business executive turned politician During the latter stages of the 2016 American election campaign, libertarian billionaire Peter Theil claimed that Americans supportive of Donald Trump's candidacy–including himself–were taking Trump 'seriously but not literally' (Yarow, 2016), which implied that those opposed to Trump's candidacy took him literally but not seriously. -

Buzzfeed Newsннdepartment of Interior FOIA Request

7/13/2015 DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Mail BuzzFeed NewsDepartment of Interior FOIA Request OS, OS FOIA <[email protected]> BuzzFeed NewsDepartment of Interior FOIA Request 1 message Christopher Massie <[email protected]> Mon, Jul 13, 2015 at 12:48 PM To: [email protected] Dear FOIA Public Liaison: This is a request under the Freedom of Information Act. I request that a copy of the following documents (or documents containing the following information) be provided to me (identify the documents or information as specifically as possible): All Department of Interior records containing the name Donald Trump and/or the words "Trump Organization" ranging from January 1, 1980 to July 13, 2015. In order to help to determine my status to assess fees, you should know that I am a representative of the news media/press and this request is made as part of news gathering and not for commercial use. The maximum dollar amount I am willing to pay for this request is $(insert maximum dollar amount). Please notify me if the fees will exceed $25.00 or the maximum dollar amount I entered. Thank you for your consideration of this request. Sincerely, Christopher Massie 9143101077 19 W. 22 St. New York, NY 10010 [email protected] https://mail.google.com/mail/b/322/u/0/?ui=2&ik=793d2a3fcf&view=pt&search=inbox&th=14e88518dca7547e&siml=14e88518dca7547e 1/1 1/13/2016 DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Mail FOIA Request OS, OS FOIA <[email protected]> FOIA Request 2 messages Abraham Payton <[email protected]> Tue, Jan 12, 2016 at 8:46 PM To: [email protected] Tuesday, January 12, 2016 Clarice Julka FOIA Officer Department of Interior MS7328, MIB 1849 C Street, NW Washington, DC 20240 Phone: (202) 2086045 Fax: (202) 2192374 Email: [email protected] To Whom It May Concern, The following request is being made in accordance with the Freedom of Information Act (5 U.S.C. -

Donald Trump: a Critical Theory-Perspective on Authoritarian Capitalism

tripleC 15(1): 1-72, 2017 http://www.triple-c.at Donald Trump: A Critical Theory-Perspective on Authoritarian Capitalism Christian Fuchs University of Westminster, London, UK, [email protected], @fuchschristian Abstract: This paper analyses economic power, state power and ideological power in the age of Donald Trump with the help of critical theory. It applies the critical theory approaches of thinkers such as Franz Neumann, Theodor W. Adorno and Erich Fromm. It analyses changes of US capitalism that have together with political anxiety and demagoguery brought about the rise of Donald Trump. This article draws attention to the importance of state theory for understanding Trump and the changes of politics that his rule may bring about. It is in this context important to see the complexity of the state, including the dynamic relationship be- tween the state and the economy, the state and citizens, intra-state relations, inter-state rela- tions, semiotic representations of and by the state, and ideology. Trumpism and its potential impacts are theorised along these dimensions. The ideology of Trump (Trumpology) has played an important role not just in his business and brand strategies, but also in his political rise. The (pseudo-)critical mainstream media have helped making Trump and Trumpology by providing platforms for populist spectacles that sell as news and attract audiences. By Trump making news in the media, the media make Trump. An empirical analysis of Trump’s rhetoric and the elimination discourses in his NBC show The Apprentice underpins the analysis of Trumpology. The combination of Trump’s actual power and Trump as spectacle, showman and brand makes his government’s concrete policies fairly unpredictable. -

Should I Vote for Donald Trump? “I Have the Best Words.” Donald Trump, December 2015

Should I vote for Donald Trump? “I have the best words.” Donald Trump, December 2015 [If you close plants in Michigan] you’ll come back to Michigan because those guys are going to want their jobs back even if it [pays] less. “ Donald Trump, in an interview with the Detroit News, discussing his plan to cut workers’ pay I like the Right-to-Work, but the union people, people in unions, they seem to really want to vote for me. It’s been amazing. “ Donald Trump, February 2016 Our wages are too high. We have “ to compete with other countries. Donald Trump, 2015 Privatization [of social security] would be good for all of us. “ Donald Trump, after calling Social Security a Ponzi Scheme How does Donald Trump treat workers? At least 60 lawsuits, along with hundreds of liens, judgments, and other government filings document people who have accused 60 lawsuits for Trump and his businesses of failing to pay them for their work, including: A dishwasher, a glass company, a carpet company, failure to pay a plumber, painters, 48 waiters, dozens of bartenders and hourly workers, real estate brokers, and ultimately, several law firms that workers once represented him in these kinds of lawsuits. USA Today Network, June 9, 2016 Trump’s companies have also been cited for 24 violations of the Fair 24 violations Labor Standards Act since 2005 for failing to pay overtime or minimum wage, according to U.S. Department of Labor data. of the Fair Labor That includes 21 citations against the defunct Trump Plaza and 3 against the also out-of-business Trump Mortgage LLC. -

Your God Is Too Successful Rich Nathan October 10-11, 2015 Your God Is Too…Series 2 Kings 5.1-15

Your God is Too Successful Rich Nathan October 10-11, 2015 Your God Is Too…Series 2 Kings 5.1-15 How many of you are familiar with this man? Photo of Donald Trump (please don’t identify the photo) Of course, that is Donald Trump, who has promised to take the United States’ brand and make it great again. Donald Trump is known for naming his companies after him, so there Trump Airlines Trump Vodka Trump Casinos Trump: The Game Trump Magazine Trump Steaks Go Trump.com Trump University Trump Mortgage Trump Search Engine All of those companies went out of business or went bankrupt. And then there are his successful companies: Trump Towers Trump Place The Apprentice The Trump International Tower in Chicago How many of you are familiar with this man? Photo of Norman Borlaug (please don’t identify the photos) This is Norman Borlaug, who is the Father of the Green Revolution and is called the man who saved a billion lives. Norman Borlaug won the Nobel Peace Prize, the Presidential Medal of 1 © 2015 Rich Nathan | VineyardColumbus.org Freedom and the Congressional Gold Medal. What made Norman Borlaug so great is that as a plant pathologist and geneticist, Borlaug introduced high-yielding varieties of wheat and other grains to Mexico to Pakistan to India to South America and to Africa. He turned nations like India and Pakistan, who had regularly experience famine in the past, into exporters of grain. The Green Revolution that he fathered has been said to have saved a billion people from starvation. -

JMBM's Global Hospitality Group® Unequaled Hotel Experience

GHG CREDENTIALS The 3 most important factors for your hospitality project… Experience Experience Experience JMBM’s Global Hospitality Group® Unequaled hotel experience JEFFER MANGELS BUTLER & MITCHELL LLP The premier hospitality practice in a full-service law firm™ Global Hospitality Group® Representative Clients Experience is the key to better results on important matters. We have more experience with more hotel properties in more locations than any other law firm in the world. We have helped clients with more than 4,300 hospitality properties valued at more than $104.7 billion. We do not need offices around the globe to bring our international expertise to your hotel matter, because most of our work is done by virtual meetings, email and conference calls. We transparently work across all time zones, making our physical office location immaterial. This is nothing new for us; we have serviced clients worldwide for decades. The Representative Clients listed below show how JMBM’s Global Hospitality Group® have used their international hotel experience to help clients big and small all over the world. Company Transaction Description 3Wall Development Represented the company in a broad range of hospitality matters involving acquisition, financing, management, joint venture structuring and labor for the Sheraton Gunter Hotel in San Antonio, the Hilton Garden Inns in Rancho Mirage and Tampa, the Doubletree Tucson at Reid Park, and the Sheraton Four Points LAX in Los Angeles. Work also included NLRB arbitrations regarding neutrality agreement, collective bargaining with UNITE HERE and class action litigation involving the application of a service charge ordinance to the hotel. 5810 Scatterfield Road, LP Represented the company in litigation relating to a “first-class” condition requirement in the ground lease for a hotel in Anderson, Indiana. -

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27

Case 2:19-cv-01501-MCE-DB Document 10 Filed 08/08/19 Page 1 of 3 1 Bryan K. Weir, CA Bar #310964 Thomas R. McCarthy* 2 William S. Consovoy* 3 Cameron T. Norris* CONSOVOY MCCARTHY PLLC 4 1600 Wilson Boulevard, Suite 700 Arlington, VA 22209 5 (703) 243-9423 6 *Application for admission 7 pro hac vice pending UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 8 EASTERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 9 10 11 DONALD J. TRUMP FOR PRESIDENT, No. 19-cv-1501 INC., DONALD J. TRUMP, in his 12 capacity as a private citizen, 13 Plaintiffs, NOTICE OF MOTION AND MOTION FOR PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION 14 v. 15 ALEX PADILLA, in his official capacity as California Secretary of State, and 16 XAVIER BECERRA, in his official capacity as California Attorney General, 17 Defendants. 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 Case 2:19-cv-01501-MCE-DB Document 10 Filed 08/08/19 Page 2 of 3 1 NOTICE 2 Notice is hereby given that Plaintiffs Donald J. Trump for President, Inc. and President 3 Donald J. Trump, in his capacity as a private citizen, make the following motion, which they 4 propose to notice for a hearing on September 5, 2019. 5 MOTION 6 Plaintiffs hereby move for a preliminary injunction enjoining enforcement of the provisions 7 of the Presidential Tax Transparency and Accountability Act, enacted though Senate Bill 27 8 (“SB27”), that require candidates for the presidency to disclose their tax returns as a condition of 9 appearing on a primary ballot. See Cal. Elec. Code §§ 6880-6884. -

2018.10.29 Complaint (Final) Compared With

Case 1:18-cv-09936-LGS Document 78-1 Filed 01/31/19 Page 1 of 204 EXHIBIT A Case 1:18-cv-09936-LGS Document 78-1 Filed 01/31/19 Page 2 of 204 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK JANE DOE, LUKE LOE, RICHARD ROE, and MARY MOE, individually and on behalf of all others similarly situated, Plaintiffs, v. No. _______________________1:18- THE TRUMP CORPORATION, DONALD J. cv-09936-LGS TRUMP, in his personal capacity, DONALD TRUMP JR., ERIC TRUMP, and IVANKA TRUMP, JURY TRIAL DEMANDED Defendants. AMENDED CLASS ACTION COMPLAINT Case 1:18-cv-09936-LGS Document 78-1 Filed 01/31/19 Page 3 of 204 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 1 PARTIES .................................................................................................................................. 1112 A. Plaintiffs ............................................................................................................ 1112 B. Defendants ........................................................................................................ 1113 JURISDICTION AND VENUE ............................................................................................... 1214 FACTS ...................................................................................................................................... 1315 I. THE TRUMP ENTERPRISE ....................................................................................... 1315 A. The Trump -

MULTI-FAMILY Architecture and Planning Lessard D E S I G N

MULTI-FAMILY Architecture and Planning lessard D E S I G N LESSARD DESIGN is an international architecture and planning firm committed to creating environments that inspire connection, collaboration, community and commerce. © Lessard Design 2016. we design lessard lessardSTUDIO community. STUDIO Lessard Design is an international architecture and planning firm committed to creating environments that inspire connection, collaboration, community and commerce. Headquartered in the Washington, DC Metropolitan area, we have offices in New York, and Ahmedabad, India. Our award winning designs have been featured in the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, Urban Land Magazine, American Builders Quarterly, Design, Builder Magazine, Building Design & Construction, Multifamily Trends, Green Business Quarterly, and Inform Architecture & Design. Lessard firm leaders have experience working in nearly 20 countries with projects in the Americas, Europe, Asia and the Middle East. Our understanding of global cultures is translated through design that is sensitive to cultural geographies, communities, traditions and values. Lessard’s diverse mulit-disciplinary team provides the expertise to manage clients through all design phases – from feasibility, strategy and through construction. © Lessard Design 2016. lessard D E S I G N LESSARD STUDIO Lessard Studio RESIDENTIAL DESIGN THERE’S NO PLACE LIKE HOME: The residential landscape is Our architects and planners support the public review processes changing. Transit-oriented development delivers the opportunity as a vital component to achieving objectives. We’re industry leaders to live, work, and play close to home, encouraging sustainable in residential design. It’s apparent in our communication, lifestyles and environments. Lessard Design works closely with collaboration, and commitment to clients and community. -

The Trump Brand

NewYorkNewYork The Trump Brand An Interview with Donald J. Trump, Chairman, President, and Chief Executive Offi cer, The Trump Organization EDITORS’ NOTE Donald Trump is The U.S. needs leadership and The Trump Hotel Collection has con- the author of 15 best-selling books, strong negotiators, both of which are tinued to grow and expand into new markets. including The Art of the Deal, The lacking. We cannot continue to blunder What are the key characteristics of a Trump ho- Art of the Comeback, How to Get our way through international relations tel and how large can the collection become? Rich, Think Like a Billionaire, Never and permit the blunders and scandals The world is a big place and the Trump Give Up, Why We Want You To Be that erupt on an almost daily basis na- Hotel Collection can handle that. There are Rich, Think Like a Champion, Midas tionally. We have lost our position as a not many boundaries when it comes to a gold Touch, and Time To Get Tough. He global leader and we have not set a good standard hotel. Cities want the Trump presence serves on the board of the Police example for our youth. It’s not a climate and we are often asked to build in a variety of Athletic League and is Chairman of for idealism or strong values and that is countries. The key characteristic is the highest the Donald J. Trump Foundation. a disservice to our young people. quality available on every level. We are known Trump is also the co-producer and As a leading entrepreneur, for our impeccable service and thoughtfulness star of The Apprentice and Celebrity Donald J.