Geesin Mollan Trump and Trumpism FINAL

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Periodicalspov.Pdf

“Consider the Source” A Resource Guide to Liberal, Conservative and Nonpartisan Periodicals 30 East Lake Street ∙ Chicago, IL 60601 HWC Library – Room 501 312.553.5760 ver heard the saying “consider the source” in response to something that was questioned? Well, the same advice applies to what you read – consider the source. When conducting research, bear in mind that periodicals (journals, magazines, newspapers) may have varying points-of-view, biases, and/or E political leanings. Here are some questions to ask when considering using a periodical source: Is there a bias in the publication or is it non-partisan? Who is the sponsor (publisher or benefactor) of the publication? What is the agenda of the sponsor – to simply share information or to influence social or political change? Some publications have specific political perspectives and outright state what they are, as in Dissent Magazine (self-described as “a magazine of the left”) or National Review’s boost of, “we give you the right view and back it up.” Still, there are other publications that do not clearly state their political leanings; but over time have been deemed as left- or right-leaning based on such factors as the points- of-view of their opinion columnists, the make-up of their editorial staff, and/or their endorsements of politicians. Many newspapers fall into this rather opaque category. A good rule of thumb to use in determining whether a publication is liberal or conservative has been provided by Media Research Center’s L. Brent Bozell III: “if the paper never met a conservative cause it didn’t like, it’s conservative, and if it never met a liberal cause it didn’t like, it’s liberal.” Outlined in the following pages is an annotated listing of publications that have been categorized as conservative, liberal, non-partisan and religious. -

Juliana Geran Pilon Education

JULIANA GERAN PILON [email protected] Dr. Juliana Geran Pilon is Research Professor of Politics and Culture and Earhart Fellow at the Institute of World Politics. For the previous two years, she taught in the Political Science Department at St. Mary’s College of Maryland. From January 1991 to October 2002, she was first Director of Programs, Vice President for Programs, and finally Senior Advisor for Civil Society at the International Foundation for Election Systems (IFES), after three years at the National Forum Foundation, a non-profit institution that focused on foreign policy issues - now part of Freedom House - where she was first Executive Director and then Vice President. At NFF, she assisted in creating a network of several hundred young political activists in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union. For the past thirteen years she has also taught at Johns Hopkins University, the Institute of World Politics, George Washington University, and the Institute of World Politics. From 1981 to 1988, she was a Senior Policy Analyst at the Heritage Foundation, writing on the United Nations, Soviet active measures, terrorism, East-West trade, and other international issues. In 1991, she received an Earhart Foundation fellowship for her second book, The Bloody Flag: Post-Communist Nationalism in Eastern Europe -- Spotlight on Romania, published by Transaction, Rutgers University Press. Her autobiographical book Notes From the Other Side of Night was published by Regnery/Gateway, Inc. in 1979, and translated into Romanian in 1993, where it was published by Editura de Vest. A paperback edition appeared in the U.S. in May 1994, published by the University Press of America. -

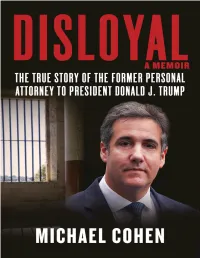

2020 Michael Cohen

Copyright © 2020 by Michael Cohen All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018. Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or [email protected]. Skyhorse® and Skyhorse Publishing® are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc.®, a Delaware corporation. Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file. ISBN: 978-1-5107-6469-9 eBook: 978-1-5107-6470-5 Cover design by Brian Peterson Cover photographs by Getty Images All interior photos © 2020 Michael Cohen Printed in the United States of America Dedication I dedicate this book to the love of my life, my wife Laura, and to my wonderful children, Samantha and Jake. The three of you endured so much during my years with Donald Trump and in the years since then. You have been subjected to harassment, insults and threats; you have seen me get arrested and charged and put in prison (twice). But the deepest suffering must have come as you watched me play an active role in the despicable acts of Mr. -

Republican Goveners Association America 2024 Namun 2019

REPUBLICAN GOVENERS ASSOCIATION AMERICA 2024 NAMUN 2019 Table of Contents Table of Contents 1 Letter from the Chair 4 Letter from the Director 5 Introduction 6 Definitions 6 Historical Background I: Federalism 7 Federalism in the United States 7 Federalism in the Constitution 7 Federalism in Reality 8 Federalism in Jurisprudence 8 Federalism and Presidentialism 9 Federalism and the Congress 10 Moving Forward: A New Federalist Framework? 12 Historical Context II: Contemporary American Politics 12 Donald Trump 12 2016 Election 13 Russian Interference in the 2016 Election and Wiki Leaks 13 2018 Congressional Elections 13 2020 Presidential Election 14 2022 Congressional Elections 14 2024 Presidential Election 14 Timeline 15 Issues 16 Overview 16 Republicans 16 Democrats 16 Economy 17 Healthcare 17 Repealing and Replacing Obamacare 18 Immigration 19 Race 19 Task of the Committee 20 2 www.namun.org / [email protected] / @namun2019 The State of Affairs 20 Call to Action 20 Questions to Consider 20 Sources 21 Appendices 23 Appendix A: 2016 Electoral Map 23 Appendix B: 2024 Electoral Map 23 Appendix C: “The Blue Wall.” 23 Appendix D: Total U.S National Debt 24 Appendix E: Intragovernmental Debt 24 Appendix F: Public Debt 25 Appendix G. Ideology Changes in the Parties 26 Bibliography 27 3 www.namun.org / [email protected] / @namun2019 Letter from the Chair Dear Delegates, It is with great pleasure that I welcome you the Republican Governors of America 2024. I’d like to thank you for expressing your interest in this committee. My name is Michael Elliott and I will be the chair for this committee. -

The Civil War in the American Ruling Class

tripleC 16(2): 857-881, 2018 http://www.triple-c.at The Civil War in the American Ruling Class Scott Timcke Department of Literary, Cultural and Communication Studies, The University of The West Indies, St. Augustine, Trinidad and Tobago, [email protected] Abstract: American politics is at a decisive historical conjuncture, one that resembles Gramsci’s description of a Caesarian response to an organic crisis. The courts, as a lagging indicator, reveal this longstanding catastrophic equilibrium. Following an examination of class struggle ‘from above’, in this paper I trace how digital media instruments are used by different factions within the capitalist ruling class to capture and maintain the commanding heights of the American social structure. Using this hegemony, I argue that one can see the prospect of American Caesarism being institutionally entrenched via judicial appointments at the Supreme Court of the United States and other circuit courts. Keywords: Gramsci, Caesarism, ruling class, United States, hegemony Acknowledgement: Thanks are due to Rick Gruneau, Mariana Jarkova, Dylan Kerrigan, and Mark Smith for comments on an earlier draft. Thanks also go to the anonymous reviewers – the work has greatly improved because of their contributions. A version of this article was presented at the Local Entanglements of Global Inequalities conference, held at The University of The West Indies, St. Augustine in April 2018. 1. Introduction American politics is at a decisive historical juncture. Stalwarts in both the Democratic and the Republican Parties foresee the end of both parties. “I’m worried that I will be the last Republican president”, George W. Bush said as he recoiled at the actions of the Trump Administration (quoted in Baker 2017). -

Neoconservatives Among Us? Astudy of Former Dissidents' Discourse

43 L 62 Neoconservatives Among Us? A Study of Former Dissidents’ Discourse* JENI SCHALLER Abstract: Neoconservative political thought has been characterized as “distinctly American”, but could there be fertile ground for its basic tenets in post-communist Europe? This paper takes an initial look at the acceptance of the ideas of American neo- conservative foreign policy among Czech elites who were dissidents under the communist regime. Open-ended, semi-structured interviews with eight former dissidents were con- ducted and then analyzed against a background of some fundamental features of neocon- servative foreign policy. Discourse analysis is the primary method of examination of the texts. Although a coherent discourse among Czech former dissidents cannot be said to ex- ist, certain aspects reminiscent of American neoconservative thought were found. Key words: neoconservatism, Czech dissidents, foreign policy, discourse analysis I. INTRODUCTION Neoconservatism, as a strain of political thought in the United States, has been represented as “distinctly American” and Irving Kristol, often considered the “godfather” of neoconservatism, emphatically states “[t]here is nothing like neoconservatism in Europe” (Kristol 2003: 33). Analyst Jeffrey Gedmin writes that the “environment for neoconservatism as such is an inhospitable one” in Europe, especially Germany (Gedmin 2004: 291). The states of Cen- tral Europe, in contrast to many of the established continental EU members, represent a rather more pro-American stance. With groups of former dissi- dents whose political leanings are in part informed by the American anti- communist, pro-democracy policies of the 1970s and 1980s, could there be a more hospitable environment for neoconservative ideas in a Central Euro- pean state such as the Czech Republic? The Czech dissident community was not as extensive or well-organised as that in Poland or even Hungary, largely due to the post-1968 “normalisation” in Czechoslovakia. -

Online Media and the 2016 US Presidential Election

Partisanship, Propaganda, and Disinformation: Online Media and the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Faris, Robert M., Hal Roberts, Bruce Etling, Nikki Bourassa, Ethan Zuckerman, and Yochai Benkler. 2017. Partisanship, Propaganda, and Disinformation: Online Media and the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election. Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society Research Paper. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33759251 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA AUGUST 2017 PARTISANSHIP, Robert Faris Hal Roberts PROPAGANDA, & Bruce Etling Nikki Bourassa DISINFORMATION Ethan Zuckerman Yochai Benkler Online Media & the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This paper is the result of months of effort and has only come to be as a result of the generous input of many people from the Berkman Klein Center and beyond. Jonas Kaiser and Paola Villarreal expanded our thinking around methods and interpretation. Brendan Roach provided excellent research assistance. Rebekah Heacock Jones helped get this research off the ground, and Justin Clark helped bring it home. We are grateful to Gretchen Weber, David Talbot, and Daniel Dennis Jones for their assistance in the production and publication of this study. This paper has also benefited from contributions of many outside the Berkman Klein community. The entire Media Cloud team at the Center for Civic Media at MIT’s Media Lab has been essential to this research. -

Tiered Balancing and the Fate of Roe V. Wade: How the New Supreme Court Majority Could Turn the Undue-Burden Standard Into a Deferential Pike Test

TIERED BALANCING AND THE FATE OF ROE V. WADE: HOW THE NEW SUPREME COURT MAJORITY COULD TURN THE UNDUE-BURDEN STANDARD INTO A DEFERENTIAL PIKE TEST By Brendan T. Beery* In one of the more noteworthy uses of his much-ballyhooed “swing vote”1 on the U.S. Supreme Court, Justice Anthony Kennedy sided with Justices Breyer, Ginsburg, Sotomayor, and Kagan in striking down two Texas laws that restricted access to reproductive- healthcare facilities. The laws did so by imposing toilsome admitting privileges and surgical-facility standards that clinics had difficulty abiding. 2 The proposition that a woman has an unenumerated constitutional right to terminate a pregnancy, at least before the point of fetal viability, won the day in 1973.3 But, as 2018 fades into 2019, no judicial precedent is more endangered than the one that has evolved in a triumvirate of cases: Roe v. Wade,4 Planned Parenthood v. Casey,5 and Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt,6 save perhaps the principle * Professor of Law, Western Michigan University Thomas M. Cooley Law School; B.A., Bradley University, 1995; J.D., summa cum laude, Thomas M. Cooley Law School, 1998. The author wishes to thank his friend and colleague, Professor Daniel R. Ray, for his assistance in conceptualizing this essay. The author also thanks the editors and staff of the Kansas Journal of Law & Public Policy for their incisive feedback, professionalism, and hard work. 1 See Caitlin E. Borgmann, Abortion, the Undue Burden Standard, and the Evisceration of Women’s Privacy, 16 WM. & MARY J. WOMEN & L. 291, 292 (2010). -

1 - Centre Stage and Our Debate Underway

Munk Debate on the US Election September 30, 2016 Rudyard Griffiths: This is the heart of downtown Toronto, a city that is home to more than six million people, the skyline carved in the waters of Lake Ontario and here we are, everyone, at Roy Thomson Hall. Its distinctive exterior design, we know it well, reflective by day, transparent by night. This is Toronto’s premier concert hall. It’s a venue usually for the biggest names in entertainment, but tonight before 3,000 people the latest in a series of Munk Debates, a clash of ideas over the US presidential election. Good evening, my name is Rudyard Griffiths and it is once again my pleasure to be your moderator tonight for this debate, this important debate. I want to start by welcoming the North American wide television audience tuning in right now C-SPAN across the continental US and here in Canada coast to coast on CPAC. A warm hello also to the online audience watching right now; Facebook Live streaming this debate over facebook.com, our social media partner, on the websites of our digital and print partner theglobeandmail.com and, of course, on our own website themunkdebates.com and a hello to all of you, the 3,000 people who have once again filled Roy Thomson Hall to capacity. Bravo. Our ability year in and year out, debate in and debate out to bring to you some of the world’s best debaters, some of the brightest minds, the sharpest thinkers to weigh in on the big global challenges, issues and problems facing the world would not be possible without the generosity, the foresight and the commitment of our host tonight. -

COURSE SYLLABUS US Politics and Foreign Policy in the Age of Trump

COURSE SYLLABUS U.S. Politics and Foreign Policy in the Age of Trump Central European University Fall 2020 4 Credits (8 ECTS Credits) Co-Instructors Erin Jenne, PhD Professor, International Relations Dept. [email protected] Levente Littvay, PhD Professor, Political Science Dept. [email protected] Teaching Assistants Michael Zeller, Doctoral Candidate, Political Science Dept. [email protected] Semir Dzebo Doctoral Candidate, International Relations Dept. [email protected] Important Note About the Course Format This course is designed for online delivery. It includes pre-recorded lectures, individual and group activities, a discussion forum where all class related questions can be discussed amongst the students and with the team of instructors. There is 1 hour and 40 minutes set aside each week for synchronous group activities. For these, if necessary, students will be grouped into a European morning (11 am - 12:40 pm CET) and evening (17:20 - 19:00 pm CET) session to accommodate potential timezone issues. (Around the time of the election, we may schedule more. And forget timezones, or sleep, on November 2, 3 and 4.) This course does not meet in person, but, nonetheless, the goal is to make it useful and fun. The course is open to CEU students on-site in Vienna or scattered anywhere across the globe. We welcome MA and PhD students from any department who wish to see the political science perspective on the elections and would like to get some hands on American Politics research experience. Course Description While most courses focus on either the domestic or the foreign policy aspect of U.S. -

Conservative Movement

Conservative Movement How did the conservative movement, routed in Barry Goldwater's catastrophic defeat to Lyndon Johnson in the 1964 presidential campaign, return to elect its champion Ronald Reagan just 16 years later? What at first looks like the political comeback of the century becomes, on closer examination, the product of a particular political moment that united an unstable coalition. In the liberal press, conservatives are often portrayed as a monolithic Right Wing. Close up, conservatives are as varied as their counterparts on the Left. Indeed, the circumstances of the late 1980s -- the demise of the Soviet Union, Reagan's legacy, the George H. W. Bush administration -- frayed the coalition of traditional conservatives, libertarian advocates of laissez-faire economics, and Cold War anti- communists first knitted together in the 1950s by William F. Buckley Jr. and the staff of the National Review. The Reagan coalition added to the conservative mix two rather incongruous groups: the religious right, primarily provincial white Protestant fundamentalists and evangelicals from the Sunbelt (defecting from the Democrats since the George Wallace's 1968 presidential campaign); and the neoconservatives, centered in New York and led predominantly by cosmopolitan, secular Jewish intellectuals. Goldwater's campaign in 1964 brought conservatives together for their first national electoral effort since Taft lost the Republican nomination to Eisenhower in 1952. Conservatives shared a distaste for Eisenhower's "modern Republicanism" that largely accepted the welfare state developed by Roosevelt's New Deal and Truman's Fair Deal. Undeterred by Goldwater's defeat, conservative activists regrouped and began developing institutions for the long haul. -

The Evolution of the Digital Political Advertising Network

PLATFORMS AND OUTSIDERS IN PARTY NETWORKS: THE EVOLUTION OF THE DIGITAL POLITICAL ADVERTISING NETWORK Bridget Barrett A thesis submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at the Hussman School of Journalism and Media. Chapel Hill 2020 Approved by: Daniel Kreiss Adam Saffer Adam Sheingate © 2020 Bridget Barrett ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Bridget Barrett: Platforms and Outsiders in Party Networks: The Evolution of the Digital Political Advertising Network (Under the direction of Daniel Kreiss) Scholars seldom examine the companies that campaigns hire to run digital advertising. This thesis presents the first network analysis of relationships between federal political committees (n = 2,077) and the companies they hired for electoral digital political advertising services (n = 1,034) across 13 years (2003–2016) and three election cycles (2008, 2012, and 2016). The network expanded from 333 nodes in 2008 to 2,202 nodes in 2016. In 2012 and 2016, Facebook and Google had the highest normalized betweenness centrality (.34 and .27 in 2012 and .55 and .24 in 2016 respectively). Given their positions in the network, Facebook and Google should be considered consequential members of party networks. Of advertising agencies hired in the 2016 electoral cycle, 23% had no declared political specialization and were hired disproportionately by non-incumbents. The thesis argues their motivations may not be as well-aligned with party goals as those of established political professionals. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES AND FIGURES .................................................................................................................... V POLITICAL CONSULTING AND PARTY NETWORKS ...............................................................................