Wbadmi Project Impact Assessment Report- Phase 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Influence of Some Fruit Traits of Mango, Mangifera Indica L. Varieties Against Maggot Development and Infestation of Mango Fruit

Journal of Entomology and Zoology Studies 2018; 6(2): 2621-2627 E-ISSN: 2320-7078 P-ISSN: 2349-6800 Influence of some fruit traits of mango, Mangifera JEZS 2018; 6(2): 2621-2627 © 2018 JEZS indica L. varieties against maggot development Received: 07-01-2018 Accepted: 10-02-2018 and infestation of mango fruit fly, Bactrocera JS Choudhary dorsalis (Hendel) ICAR Research Complex for Eastern Region Research Centre, Plandu, Ranchi, Jharkhand, India JS Choudhary, MK Dhakar, Debu Mukherjee, Moanaro, Bikash Das, AK Singh and BP Bhatt MK Dhakar ICAR Research Complex for Eastern Region Research Centre, Abstract Plandu, Ranchi, Jharkhand, The present study (during year 2014 and 2015) examined the various fruit traits of 10 popular varieties of India mango, Mangifera indica in relation to resistance against B. dorsalis under field conditions. Results indicated significant variations among tested varieties in levels of fruit infestation and maggot density Debu Mukherjee inside the fruit. The varieties Amrapali (6.67%), Gulab Khas (20.00%) and Dashehari (15.00%) were ICAR Research Complex for found resistant; Jardalu (21.67%) and Maldah (25.00%) were moderately resistant; Himsagar (36.67%) Eastern Region Research Centre, were susceptible while Chausa (40.00%), Mallika (58.33%), Fazli (58.33%) and Bombay Green Plandu, Ranchi, Jharkhand, (61.67%) were found the highly susceptible to B. dorsalis infestation. Principal components were India extracted based on fruit traits and first four principal components explained cumulative variation of 89.97 % with eigenvalues >0.5 in B. dorsalis infestation. Mango varieties Amrapali, Gulab Khas and Dashehari Moanaro, Bikash Das ICAR Research Complex for were classified as resistant to B. -

Dr. Mahuya Hom Choudhury Scientist-C

Dr. Mahuya Hom Choudhury Scientist-C Patent Information Centre-Kolkata . The first State level facility in India to provide Patent related service was set up in Kolkata in collaboration with PFC-TIFAC, DST-GoI . Inaugurated in September 1997 . PIC-Kolkata stepped in the 4th plan period during 2012-13. “Patent system added the fuel to the fire of genius”-Abrham Lincoln Our Objective Nurture Invention Grass Root Innovation Patent Search Services A geographical indication is a sign used on goods that have a specific geographical origin and possess qualities or a reputation that are due to that place of origin. Three G.I Certificate received G.I-111, Lakshmanbhog G.I-112, Khirsapati (Himsagar) G.I 113 ( Fazli) G.I Textile project at a glance Patent Information Centre Winding Weaving G.I Certificate received Glimpses of Santipore Saree Baluchari and Dhanekhali Registered in G.I registrar Registered G.I Certificates Baluchari G.I -173-Baluchari Dhanekhali G.I -173-Dhaniakhali Facilitate Filing of Joynagar Moa (G.I-381) Filed 5 G.I . Bardhaman Mihidana . Bardhaman Sitabhog . Banglar Rasogolla . Gobindabhog Rice . Tulaipanji Rice Badshah Bhog Nadia District South 24 Parganas Dudheswar District South 24 Chamormoni ParganasDistrict South 24 Kanakchur ParganasDistrict Radhunipagol Hooghly District Kalma Hooghly District Kerela Sundari Purulia District Kalonunia Jalpaiguri District FOOD PRODUCTS Food Rasogolla All over West Bengal Sarpuria ( Krishnanagar, Nadia Sweet) District. Sarbhaja Krishnanagar, Nadia (Sweet) District Nalen gur All over West Bengal Sandesh Bardhaman Mihidana Bardhaman &Sitabhog 1 Handicraft Krishnanagar, Nadia Clay doll Dist. Panchmura, Bishnupur, Terrakota Bankura Dist. Chorida, Baghmundi 2 Chhow Musk Purulia Dist. -

Model Profile for 1.0 Ha Mango Cultivation

Model Profile for 1.0 ha Mango Cultivation 1. Introduction Mango (Mangifera indica) is the leading fruit crop of India and considered to be the king of fruits. Besides delicious taste, excellent flavour and attractive fragrance, it is rich in vitamin A&C. The tree is hardy in nature, can be grown in a variety of soil and requires comparatively low maintenance costs. Mango fruit is utilised at all stages of its development both in its immature and mature state. Raw fruits are used for making chutney, pickles and juices. The ripe fruits besides being used for desert are also utilised for preparing several products like squashes, syrups, nectars, jams and jellies. The mango kernel also contains 8-10 percent good quality fat which can be used for soap and also as a substitute for cocoa butter in confectionery. 2. Scope for Mango Cultivation and its National Importance Mango occupies about 36% of the total area under fruits (2010-11) comprising of 22.97 lakh hectares, with a total production of 151.88 lakh tonnes. Uttar Pradesh and Andhra Pradesh are having the largest area under mango each with around 23% of the total area followed by Karnataka, Bihar, Gujarat and Tamilnadu. Fresh mangoes and mango pulp are the important items of agri-exports from India. India's main export destinations for mango are UAE, Bangladesh, UK, Saudi Arabia, Nepal, Kuwait, USA and other Middle East countries with a limited quantity being shipped to European market. Although, India is the largest mango producing country, accounting about 45% of world production, the export of fresh fruit is limited to Alphonso and Dashehari varieties. -

Screening of Important Cultivators of Mango Varieties for Processing

Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytochemistry 2018; SP1: 302-303 E-ISSN: 2278-4136 P-ISSN: 2349-8234 Screening of important cultivators of mango varieties JPP 2018; SP1: 302-303 for processing Dilip Kumar Pandey Krishi Vigyan Kendra, Palamu, (Birsa Agricultural University, Dilip Kumar Pandey, SK Kamal, Sanjay Kumar Ram and Arun Kumar Ranchi, Jharkhand, India Tiwary SK Kamal Krishi Vigyan Kendra, Palamu, Abstract (Birsa Agricultural University, The nutritional and therapeutic value of mango justifies as “King of Fruits” and processing of mango Ranchi, Jharkhand, India fruits into value added products would be boon to the processor as well as grower. RTS- beverages Sanjay Kumar Ram preparation require low cost and low energy processing technology, simple and adaptable in rural Krishi Vigyan Kendra, Palamu, countryside with limited skill and resources. As the raw produce goes for processing, screening of eight (Birsa Agricultural University, important cultivars (viz Mithua, Bombay-green, Gulabkhas, Zardalu, Langra, Dashehari, Alphonso and Ranchi, Jharkhand, India Himsagar) of mango grown under Chhotanagpur plateau region of Jharkhand were undertaken. Simultaneously, encourage commercial cultivation of mango varieties suitable to grow. The screening Arun Kumar Tiwary result of cultivars show maximum average fruit weight was recorded in Himsagar (220.0 g) and Dept. of Horticulture, Birsa Dashehari had smallest fruit weight (104 g), which is too small size but still liked by people. Pulp Agricultural University, Ranchi, percentage more than 70 percent found in cv. Gulabkhas, Langra, Alphonso, Himsagar, Bombay-green Jharkhand, India and Dashehari. Maximum TSS of juice was in Langra (19.50 B). On overall screening of physico- chemical analysis of fruits and prepared RTS beverages at 150 B showed Alphonso, Himsagar and Langra are mostly accepted and Mithua and Zardalu are least accepted on 9 point Hedonic scale. -

Friday 3 March 2017

Friday 3rd March 2017 (For the period 3rd to7th March 2017) Weblink For District AAS Bulletin: http://www.imdagrimet.gov.in/node/3545 State Composite AAS Bulletin: http://www.imdagrimet.gov.in/node/3544 1 Contour maps for Mean Maximum and Minimum Temperature and their anomaly for the week ending on 01.03.2017 Actual Mean Maximum Temperature (oC) in India for the Mean Maximum Temperature (oC) Anomaly in India for week ending 01.03.2017 the week ending 01.03.2017 Mean maximum temperature was between 36 to 400C over Mean maximum temperature was above normal by 4 to many parts of North Interior Karnataka, Rayalaseema, 60C over some parts of Saurashtra & Kutch and isolated some parts of Madhya Maharashtra, Marathwada, pockets of Himachal Pradesh, West Rajasthan and Gujarat Telangana, South Interior Karnataka and isolated pockets Region. of Gujarat, Odisha and Tamil Nadu. Mean maximum temperature was above normal by 2 to Mean maximum temperature was between 32 to 360C over 40C over Punjab, Haryana & Delhi, many parts of Jammu Vidarbha, Konkan & Goa, Coastal Karnataka, Kerala, & Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh, Rajasthan, Gujarat, Lakshadweep, many parts of Gujarat, Madhya Vidarbha, Madhya Maharashtra, Konkan & Goa, Maharashtra, Marathwada, Chhattisgarh, Odisha, Karnataka, Telangana, Rayalaseema, some parts of Uttar Telangana, Coastal Andhra Pradesh, South Interior Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Jharkhand, Odisha, Kerala, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, some parts of West Rajasthan, Tamil Nadu, Lakshadweep and isolated pockets of Madhya Pradesh, Jharkhand, Gangetic West Bengal, Uttarakhand and Chhattisgarh. Rayalaseema and isolated pockets of East Rajasthan and It was normal to near normal over rest of the country. North Interior Karnataka. -

List of Ad-Hoc Panel 2013-14

Department of Economics Delhi School of Economics University of Delhi List of candidates recommended for Ad-hoc Assistant Professor in Economics under various Colleges of Delhi University for the Academic Year 2013-14 for various Categories (not in order of merit). General Category S.No. Name Address Contact No. Qualification Category 1 Md. Izhar Alam E-110/A, 2nd Floor, Nr. Hari Kothi, 9717210868 B.A. - Bihar Uni. I Abul Fazal Enclave-I, M.A. -AM Uni. Jamia Nagar, Okhla, New Delhi-25 Ph.D. -AM Uni. 2 MD. Umar Farooque C/o.- Ravindar Ji, House No. 144, Third 8130946234 B.A. - BRABU I Floor, Room No-38, Taimoor Nagar, New 9939976004 M.A. - BRABU Delhi-65 Ph.D.- BRABU & NET 3 Shalini Agarwal C-1/118, Opposite St. Marks School, 9717029113 B.A. - Deemed Uni I Janakpuri, N. Delhi 9810739947 M.A. - DBRA Uni. Ph.D.- Deemed Uni. 4 Sanjeev Kumar FF-I, Plot No-55, Gyan Khand-I, 9953531181 B.Sc. - CCS Uni. I Indirapuram, Ghaziabad (UP)-201010 M.A. - CCS Uni. M.Phil. - CCS Uni. Ph.D. - CCS Uni. & NET 5 Geeta Rani Flat No. 2057, Tower-4, Block-D, GH-7, 9999098885 B.A. - CCS Uni. I Crossing Repulik, Ghaziabad(UP) M.A. - CCS Uni. M.Phil. - CCS Uni. Ph.D. - CCS Uni. & NET 6 Renu Sinha 35/10,First Floor, West Patel Nagar, 9999119858 B.A. - Patna University I New Delhi-8 9811119858 M.A.- Patna University Ph.D. - T.M.B. University & NET 7 Garima Malik D-4/4091, Vasant Kunj, New Delhi-70 9899429072 B.A. -

Greater Bangladesh

Annexure 3 Plan to Create Greater Bangla Desh including Assam in it Greater Bangladesh From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Greater Bangladesh (translated variously as Bengali : , Brihat Bangladesh ;[1] Bengali : Brihad Bangladesh ;[2] Bengali : , Maha Bangladesh ;[3] and Bengali : , Bishal Bangla [4] ) is a political theory circulated by a number of Indian politicians and writers that People's Republic of Bangladesh is trying for the territorial expansion to include the Indian states of West Bengal , Assam and others in northeastern India. [5] The theory is principally based on fact that a large number of Bangladeshi illegal immigrants reside in Indian territory. [6] Contents [hide ] 1 History o 1.1 United Bengal o 1.2 Militant organizations 2 Illegal immigration o 2.1 Lebensraum theory o 2.2 Nellie massacre o 2.3 The Sinha Report 3 References [edit ]History The ethno-linguistic region of Bengal encompasses the territory of Bangladesh and the Indian state of West Bengal , as well as parts of Assam and Tripura . During the rule of the Hindu Sena dynasty in Bengal the notion of a Greater Bangladesh first emerged with the idea of uniting Bengali-speaking people in the areas now known as Orissa , Bihar and Indian North East (Assam, Tripura, and Meghalaya ) along with the Bengal .[7] These areas formed the Bengal Presidency , a province of British India formed in 1765, though Assam including Meghalaya and Sylhet District was severed from the Presidency in 1874, which became the Province of Assam together with Lushai Hills in 1912. This province was partitioned in 1947 into Hindu -majority West Bengal and Muslim - majority East Bengal (now Bangladesh) to facilitate the creation of the separate Muslim state of Pakistan , of which East Bengal became a province. -

Evaluation of Mango (Mangifera Indical.) Cultivars for Flowering

International Journal of Bio-resource and Stress Management 2017, 8(4):505-509 Full Research Doi: HTTPS://DOI.ORG/10.23910/IJBSM/2017.8.4.1811a Evaluation of Mango (Mangifera indica L.) Cultivars for Flowering, Fruiting and Yield Attributes T. S. Hada*and A. K. Singh Dept. of Horticulture, Institute of Agricultural Sciences, Banaras Hindu University Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh (221 005), India Corresponding Author Article History T. S. Hada Article ID: AR1811a e-mail: [email protected] Received in 3rd May, 2017 Received in revised form 29th June, 2017 Accepted in final form 4th August, 2017 Abstract A field experiment was conducted to investigate the flowering, fruiting and yield attributes of some mango cultivars for the years 2014−15 and 2015−16. Outcome of the present research work revealed that the date of panicle emergence in different mango cultivars varied in both the years. It was observed that the panicle emergence was earliest in Gulabkhas and late in Fazli in both the years. Chausa produced maximum panicle length (35.19 cm) and breadth (24.76 cm). In the year 2014−15, earliest flowering was noted in Gulabkhas (Feb 17−Feb 26) and in the year 2015−16, earliest flowering was observed in Bombai (Feb 20−Feb 28) while, flowering was very late in Sepiya for both the years. Maximum number of flowers was observed in Langra (1839.13) while, minimum number of flowers was recorded in Amrapali (954.75). The duration of flowering varied from 22.50−36.00 days in different mango cultivars. Maximum value in terms of days was observed with Sepiya (39 days) while it was minimum (22.50 days) in case of Alphonso. -

Examination Schedule for Selection of Different Contractual Posts Under DH& FWS, Murshidabad

Examination Schedule for Selection of Different Contractual Posts under DH& FWS, Murshidabad Venue:- District Training Centre (DTC), (Near Zilla Parishad), Panchanantala, Berhampore, Murshidabad-742101 Roll Father/ Husband's Name of Post Name of Candidate Date of Birth Date of Examination Reporting time Type of Examination No name 1 DPC (RNTCP) Dr. Debalina Das Dutta Mr. Rabin Das 01-12-1987 20/01/2017 9:30 A.M. Interview 2 DPC (RNTCP) Bubai Das Babulal Das 15/01/1980 20/01/2017 9:30 A.M. Interview Ramesh Chandra 3 DPC (RNTCP) Kartick Chandra Mahato 01-10-1982 20/01/2017 9:30 A.M. Interview Mahato 4 DPC (RNTCP) Supriya Banerjee Lt. Samir Banerjee 03-08-1983 20/01/2017 9:30 A.M. Interview 5 DPC (RNTCP) Gopa Kundu Gupinath Kundu 08-10-1983 20/01/2017 9:30 A.M. Interview 6 DPC (RNTCP) Kinshuk Das Lt. Kalipada Das 13-06-1985 20/01/2017 9:30 A.M. Interview Somendra Kumar 7 DPC (RNTCP) Soumick Chakraborty 05-01-1987 20/01/2017 9:30 A.M. Interview Chakraborty 8 DPC (RNTCP) Biswajit Paul Swapan Kr. Paul 22/05/1983 20/01/2017 9:30 A.M. Interview 9 DPC (RNTCP) Krishna Mukherjee Adhir Kumar Mukherjee 16-11-1978 20/01/2017 9:30 A.M. Interview 10 DPC (RNTCP) MD . Ersad Hossain Late Siddique hossain 02-04-1987 20/01/2017 9:30 A.M. Interview 11 DPC (RNTCP) Najmi Alam Abdul Jalil 02-08-1989 20/01/2017 9:30 A.M. Interview 12 DPC (RNTCP) Anupam Ghosh Dilip Kumar Ghosh 19-01-1978 20/01/2017 9:30 A.M. -

Effect of Different Intercrops on Yield, Quality and Shelf-Life in Mango Cv

Intl. J. Agric. Env. Biotech. 6(1):121-126 , March, 2013 Horticulture Effect of different intercrops on yield, quality and shelf-life in mango cv. Himsagar(Mangifera indica L) S.R. Singh,* B. C. Banik and M.A. Hasan Department of Fruits and Orchard Management, Faculty of Horticulture, B.C.K.V., Mohanpur , Nadia – 741252, West Bengal, India Email: [email protected] Paper no: 93 Received: 23rd September 2012 Received in revised form: 19th November 2012 Accepted: 19th January 2013 Abstract Field experiments were conducted during the period 2010-2012 to investigate the suitability and profitably with different intercrops of cowpea, frenchbean, arhar, soyabean, lentil, blackgram and chickpea in mango orchard (cv. Himsagar) was conducted at Central Research Farm, Gayeshpur, B.C.K.V., Nadia, West Bengal. The age of the plant is 7 years old with a spacing of 10x10m which provide the utilization of land space between the plants as an intercrop. Pooled data reveals that the maximum number of fruits 192.41 / tree and yield 46.09 kg / tree were found in Mango + Cowpea whereas maximum fruit weight (254.16 g) in Mango + Lentil. Most of the physical parameters such as fruit length and breadth maximum were recorded (8.20 cm and 7.21 cm respectively) in Mango + Cowpea. But, in case of peel weight (35.67 g) was highest in Mango + Soyabean whereas the higher stone weight (35.79 g) was in sole crop (Mango) only. Again, pulp weight and pulp: stone ratio (193.53 www.IndianJournals.com g and 5.80) were observed in Mango + Frenchbean respectively. -

11. MANGO PRODUCTION and EMPLOYMENT of PEOPLE in Tffls TRADE

11. MANGO PRODUCTION AND EMPLOYMENT OF PEOPLE IN TfflS TRADE 11.1. Introduction Mango is one of the most popular crops in the tropics, adapted to a wide range of soil and relatively easy to cultivate. It is universally considered as one of finest fruit in the world, and is called the "King of Fruits" in the orient and the "national fruit of India". If there was a competition to decide the best fruit in the world for taste and aroma, the Indian mango would certainly be one of the front- runners. In a year, India harvests more than 12 million tones of mangoes. Mango is not only delicious but also full of nutritional value. It is h i^ in beta-carotene, a precursor of vitamin A and is a rich source of vitamin B complex. Physico chemical characteristics of mango was studied by Ghosh, Dhua and Mitra (1985); Kundu and Ghosh (1992). Mangoes are mainly consumed fresh. One hundred grams of raw mango (edible portion) contains 81.7 gm water, 0.7 gm protein, 0.4 gm fat, 16 gm carbohydrates, and food energy of 66 calories. Mangoes are also relativel)' rich in other elements such as calcium, phosphorous, iron, potassium and magnesium. Mango is not just India's most important fruit, India is also the World's largest producer of this famous fruit accounting for approximately 52% of the total W orld production. I'he World production of mango is estimated to be around 23,851,997 MT and India produces 12,000,000 MT. Mango, Mangifera indica is endemic to South-East Asia. -

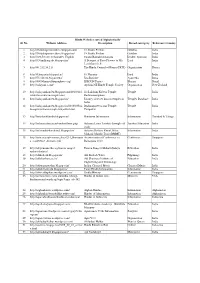

1.Hindu Websites Sorted Alphabetically

Hindu Websites sorted Alphabetically Sl. No. Website Address Description Broad catergory Reference Country 1 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.com/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 2 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.in/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 3 http://199.59.148.11/Gurudev_English Swami Ramakrishnanada Leader- Spiritual India 4 http://330milliongods.blogspot.in/ A Bouquet of Rose Flowers to My Lord India Lord Ganesh Ji 5 http://41.212.34.21/ The Hindu Council of Kenya (HCK) Organisation Kenya 6 http://63nayanar.blogspot.in/ 63 Nayanar Lord India 7 http://75.126.84.8/ayurveda/ Jiva Institute Ayurveda India 8 http://8000drumsoftheprophecy.org/ ISKCON Payers Bhajan Brazil 9 http://aalayam.co.nz/ Ayalam NZ Hindu Temple Society Organisation New Zealand 10 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.com/2010/11/s Sri Lakshmi Kubera Temple, Temple India ri-lakshmi-kubera-temple.html Rathinamangalam 11 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/ Journey of lesser known temples in Temples Database India India 12 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/2010/10/bra Brahmapureeswarar Temple, Temple India hmapureeswarar-temple-tirupattur.html Tirupattur 13 http://accidentalhindu.blogspot.in/ Hinduism Information Information Trinidad & Tobago 14 http://acharya.iitm.ac.in/sanskrit/tutor.php Acharya Learn Sanskrit through self Sanskrit Education India study 15 http://acharyakishorekunal.blogspot.in/ Acharya Kishore Kunal, Bihar Information India Mahavir Mandir Trust (BMMT) 16 http://acm.org.sg/resource_docs/214_Ramayan An international Conference on Conference Singapore