3. Indigenous Participation in the Regional Labour Market

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Grammatical Sketch of Ngarla: a Language of Western Australia Torbjörn Westerlund

UPPSALA UNIVERSITY master thesis The department for linguistics and philology spring term 2007 A grammatical sketch of Ngarla: A language of Western Australia Torbjörn Westerlund Supervisor: Anju Saxena Abstract In this thesis the basic grammatical structure of normal speech style of the Western Australian language Ngarla is described using example sentences taken from the Ngarla – English Dictionary (by Geytenbeek; unpublished). No previous description of the language exists, and since there are only five people who still speak it, it is of utmost importance that it is investigated and described. The analysis in this thesis has been made by Torbjörn Westerlund, and the focus lies on the morphology of the nominal word class. The preliminary results show that the language shares many grammatical traits with other Australian languages, e.g. the ergative/absolutive case marking pattern. The language also appears to have an extensive verbal inflectional system, and many verbalisers. 2 Abbreviations 0 zero marked morpheme 1 first person 1DU first person dual 1PL first person plural 1SG first person singular 2 second person 2DU second person dual 2PL second person plural 2SG second person singular 3 third person 3DU third person dual 3PL third person plural 3SG third person singular A the transitive subject ABL ablative ACC accusative ALL/ALL2 allative ASP aspect marker BUFF buffer morpheme C consonant CAUS causative COM comitative DAT dative DEM demonstrative DU dual EMPH emphatic marker ERG ergative EXCL exclusive, excluding addressee FACT factitive FUT future tense HORT hortative ImmPAST immediate past IMP imperative INCHO inchoative INCL inclusive, including addressee INSTR instrumental LOC locative NEG negation NMLISER nominaliser NOM nominative N.SUFF nominal class suffix OBSCRD obscured perception P the transitive object p.c. -

![AR Radcliffe-Brown]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4080/ar-radcliffe-brown-684080.webp)

AR Radcliffe-Brown]

P129: The Personal Archives of Alfred Reginald RADCLIFFE-BROWN (1881- 1955), Professor of Anthropology 1926 – 1931 Contents Date Range: 1915-1951 Shelf Metre: 0.16 Accession: Series 2: Gift and deposit register p162 Alfred Reginald Radcliffe-Brown was born on 17 January 1881 at Aston, Warwickshire, England, second son of Alfred Brown, manufacturer's clerk and his wife Hannah, nee Radcliffe. He was educated at King Edward's School, Birmingham, and Trinity College, Cambridge (B.A. 1905, M. A. 1909), graduating with first class honours in the moral sciences tripos. He studied psychology under W. H. R. Rivers, who, with A. C. Haddon, led him towards social anthropology. Elected Anthony Wilkin student in ethnology in 1906 (and 1909), he spent two years in the field in the Andaman Islands. A fellow of Trinity (1908 - 1914), he lectured twice a week on ethnology at the London School of Economics and visited Paris where he met Emily Durkheim. At Cambridge on 19 April 1910 he married Winifred Marie Lyon; they were divorced in 1938. Radcliffe-Brown (then known as AR Brown) joined E. L. Grant Watson and Daisy Bates in an expedition to the North-West of Western Australia studying the remnants of Aboriginal tribes for some two years from 1910, but friction developed between Brown and Mrs. Bates. Brown published his research from that time in an article titled “Three Tribes of Western Australia”, The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, Vol. 43, (Jan. - Jun., 1913), pp. 143-194. At the 1914 meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science in Melbourne, Daisy Bates accused Brown of gross plagiarism. -

82 3.3.4.4.3 Ecogeographic Studies of the Cranial Shape The

82 3.3.4.4.3 Ecogeographic studies of the cranial shape The measurement of the human head of both the living and dead has long been a matter of interest to a variety of professions from artists to physicians and latterly to anthropologists (for a review see Spencer 1997c). The shape of the cranium, in particular, became an important factor in schemes of racial typology from the late 18th Century (Blumenbach 1795; Deniker 1898; Dixon 1923; Haddon 1925; Huxley 1870). Following the formulation of the cranial index by Retzius in 1843 (see also Sjovold 1997), the classification of humans by skull shape became a positive fashion. Of course such classifications were predicated on the assumption that cranial shape was an immutable racial trait. However, it had long been known that cranial shape could be altered quite substantially during growth, whether due to congenital defect or morbidity or through cultural practices such as cradling and artificial cranial deformation (for reviews see (Dingwall 1931; Lindsell 1995). Thus the use of cranial index of racial identity was suspect. Another nail in the coffin of the Cranial Index's use as a classificatory trait was presented in Coon (1955), where he suggested that head form was subject to long term climatic selection. In particular he thought that rounder, or more brachycephalic, heads were an adaptation to cold. Although it was plausible that the head, being a major source of heat loss in humans (Porter 1993), could be subject to climatic selection, the situation became somewhat clouded when Beilicki and Welon demonstrated in 1964 that the trend towards brachycepahlisation was continuous between the 12th and 20th centuries in East- Central Europe and thus could not have been due to climatic selection (Bielicki & Welon 1964). -

PUBLISHED AS Smith, Nicholas 2015. “Murtuka Yirraru: Automobility in Pilbara Song-Poems”

PRE-COPYEDITED VERSION — PUBLISHED AS Smith, Nicholas 2015. “Murtuka Yirraru: Automobility in Pilbara Song-Poems”. Anthropological Forum, 25(3): 221-242. Downloaded from http://www.anthropologicalforum.net COPYRIGHT All rights held by Smith, Nicholas. You need to get the author’s permission for uses other than teaching and personal research. Murtuka yirraru: Automobility in Pilbara Song Poem Nick Smith La Trobe University - Anthropology & Sociology, Bundoora, Victoria, Australia Abstract Arguably one of the most enduring icons of modernity is the automobile. The innumerable songs about motor vehicles are testimony to this status. This article examines Pilbara Aboriginal (marrngu) songs about the murtuka (motorcar). Focussing on a particular style of song known as yirraru to Ngarla people of the De Grey River area in Western Australia, I explore a range of questions concerning the impact of automobility on marrngu life-worlds. Is the ‘freedom of the road’ a value historically shared by marrngu and walypala? Or is the marrngu passion for automobility evinced in these yirraru simply an adaptation of pre- colonial values, beliefs and behaviours associated with mobility? This is not an ethnomusicology article; I treat yirraru as narratives, narratives that convey something about the relational in marrngu modes of orientation and engagement with the motor vehicle. Using archival and ethnographic data I argue that murtuka song-poems show that marrngu regarded motor vehicles as instrumental in their own efforts for autonomy in the decades in which these yirraru originate (1920–1960s). Ultimately I consider what the enthusiastic embrace of the murtuka by marrngu might say about the nature of socio-cultural difference, similarity, and marrngu and walypala boundedness in the Pilbara. -

WA Health Language Services Policy

WA Health Language Services Policy September 2011 Cultural Diversity Unit Public Health Division WA Health Language Services Policy Contents Foreword ............................................................................................................................................................................ 1 1. Context .................................................................................................................................................................... 2 1.1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 2 1.2 Government policy obligations ................................................................................................... 2 2. Policy goals and aims .................................................................................................................................... 5 3. Scope......................................................................................................................................................................... 5 4. Guiding principles ............................................................................................................................................. 6 5. Definitions ............................................................................................................................................................... 6 6. Provision of interpreting and translating services .................................................................... -

Return of Yawuru Artefacts to Country Return of Cultural Heritage Project: Repatriation of Yawuru Cultural Heritage Material from the Manchester Museum

Return of Yawuru artefacts to Country Return of Cultural Heritage Project: Repatriation of Yawuru cultural heritage material from the Manchester Museum Iain G Johnston1, Christopher Simpson1 & Neilø McKenzie2 1 Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS). 2 Yawuru Senior Cultural Leader. First published in 2020 by the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS) Copyright © AIATSIS All rights reserved. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 (the Act), no part of this paper may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Act also allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this paper, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied or distributed digitally by any educational institution for its educational purposes, provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act. Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS) GPO Box 553, Canberra ACT 2601 Phone 61 2 6246 1111 Fax 61 2 6261 4285 Email [email protected] aiatsis.gov.au Statement of Community Authorship: The following document has been prepared in collaboration with the Senior Yawuru Ceremonial Leaders, no part may be reproduced by any process, electronic or mechanical, without prior written permission from the Senior Yawuru Ceremonial Leaders and Nyamba Buru Yawuru. -

NYIYAPARLI CLAIM DESCRIPTION Dr Bill Day Tom Price September 3, 2003

NYIYAPARLI CLAIM DESCRIPTION Dr Bill Day Tom Price September 3, 2003 1. Introduction The Nyiyaparli claim (WAG6280/98; WC99/004) covers an area of about 40,250 square kilometres in the East Pilbara. A large area taking in a number of stations, reserves and land tenures are within the claim area: - Kumarina - Pt. Bulloo Downs - Weelarrana - Sylvania - Ethel Creek - Walagunya (ALT, held by Jigalong) - Roy Hill - Marillana - Balfour Downs - Mt. Divide - Pt. Wandanya - Robertson Range Most of these leases are held privately. The exceptions are: - Marillana, Sylvania and Ethel Creek, held by BHP; - Walagunya, held by the ALT, sub-leased to Jigalong Community; - Robertson Range, held by Jigalong Community; - Mt. Divide, held by the Irrangadji Group Association. Most of the Jigalong reserve lands (including Jigalong and Camp 61) are within the claim area, and subject to further discussions between the Nyiyaparli group and the Jigalong Council about future management in light of the State Government’s Aboriginal reserve transfer program. The Nyiyaparli claim area also includes non-exclusive tenures within the town of Newman, and three substantial parcels of UCL in the west, central and southeast parts of the area. The Nyiyaparli claim is represented by the PNTS, as are the neighbouring Palyku, Martu Idja Banyjima, and IBN claims. The Martu claim (WAG6110/98; WC96/078), represented by the Ngaanyatjarra Council NTRB, adjoins much of the eastern boundary of the Nyiyaparli claim area. The Nhanuwongka Wajarri and Ngarlawanga determination area abuts parts of the claim area in the southwest and, in the north, there is a substantial area of overlap with the Nyamal claim over the area of Mt. -

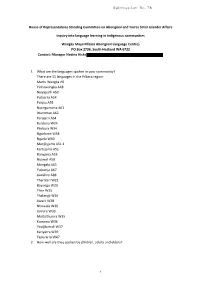

Submission No.78

House of Representatives Standing Committee on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Affairs Inquiry into language learning in Indigenous communities Wangka Maya Pilbara Aboriginal Language Centre} PO Box 2736, South Hedland WA 6722 Contact: Manager Nadine Hicks 1. What are the languages spoken in your community? There are 31 languages in the Pilbara region: Martu Wangka A6 Yinhawangka A48 Nyiyaparli A50 Putijarra A54 Palyku A55 Nyangumarta A61 Warnman A62 Karajarri A64 Burduna W24 Pinikura W34 Ngarluma W38 Ngarla W40 Manjilyjarra A51.1 Kartujarra A51 Banyjima A53 Nyamal A58 Mangala A65 Yulparija A67 Juwaliny A88 Tharrkari W21 Bayungu W23 Thiin W25 Thalanyji W26 Jiwarli W28 Nhuwala W30 Jurruru W33 Martuthunira W35 Kurrama W36 Yindjibarndi W37 Kariyarra W39 Yapurarra W47 2. How well are they spoken by children, adults and elders? 1 This varies widely. While some languages such as Thiin are no longer spoken at all, others such as Martu Wangka are widely spoken by all age groups. Detailed information for each language is available on request. 3. Describe your group and project? Wangka Maya was begun by a group of Pilbara language speakers who were concerned at the loss of languages. It aims to record and foster the Aboriginal languages of the Pilbara region. The group began with no funding working as volunteers. Gradually they attracted project funding and eventually ongoing funding as a language centre. a) Why was it important to start up? Almost no work was being done to record or foster the use of local languages. b) How long have you been running? Since 1987 c) What age group(s) are you working with? All ages. -

National Native Title Tribunal

NATIONAL NATIVE TITLE TRIBUNAL ANNUAL REPORT 1996/97 ANNUAL REPORT 1996/97 CONTENTS Letter to Attorney-General 1 Table of contents 3 Introduction – President’s Report 5 Tribunal values, mission, vision 9 Corporate overview – Registrar’s Report 10 Corporate goals Goal One: Increase community and stakeholder knowledge of the Tribunal and its processes. 19 Goal Two: Promote effective participation by parties involved in native title applications. 25 Goal Three: Promote practical and innovative resolution of native title applications. 30 Goal Four: Achieve recognition as an organisation that is committed to addressing the cultural and customary concerns of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. 44 Goal Five: Manage the Tribunal’s human, financial, physical and information resources efficiently and effectively. 47 Goal Six: Manage the process for authorising future acts effectively. 53 Regional Overviews 59 Appendices Appendix I: Corporate Directory 82 Appendix II: Other Relevant Legislation 84 Appendix III: Publications and Papers 85 Appendix IV: Staffing 89 Appendix V: Consultants 91 Appendix VI: Freedom of Information 92 Appendix VII: Internal and External Scrutiny, Social Justice and Equity 94 Appendix VIII: Audit Report & Notes to the Financial Statements 97 Appendix IX: Glossary 119 Appendix X: Compliance index 123 Index 124 National Native Title Tribunal 3 ANNUAL REPORT 1996/97 © Commonwealth of Australia 1997 ISSN 1324-9991 This work is copyright. It may be reproduced in whole or in part for study or training purposes if an acknowledgment of the source is included. Such use must not be for the purposes of sale or commercial exploitation. Subject to the Copyright Act, reproduction, storage in a retrieval system or transmission in any form by any means of any part of the work other than for the purposes above is not permitted without written permission. -

Indigenous People and the Pilbara Mining Boom a Baseline for Regional Participation

Indigenous people and the Pilbara mining boom A baseline for regional participation J. Taylor and B. Scambary Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research The Australian National University, Canberra Research Monograph No. 25 2005 Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] Web: http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-publication entry. Taylor, John, 1953 - Indigenous people and the Pilbara mining boom: A baseline for regional participation Bibliography ISBN 1 9209424 0 8 ISBN 1 9209425 4 8 (Online document) 1. Aboriginal Australians - Western Australia - Pilbara - Economic conditions. 2. Community development - Western Australia - Pilbara. 3. Sustainable development - Western Australia - Pilbara. 4. Mineral industries - Western Australia - Pilbara. 5. Pilbara (W.A.) - Economic conditions. I. Scambary, B. II. Australian National University. Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research. III. Title. (Series : Research monograph (Australian National University. Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research) ; no. 25). 362.84991509413 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopy- ing or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design by Brendon McKinley Printed by University Printing Services, ANU Table of Contents List of Figures v List of Tables vii Foreword xi Acknowledgements xiii A note on spellings of Aboriginal words xv Acronyms and abbreviations xvii 1. Profiling outcomes 1 Methods 4 Statistical geography 7 2. Demography of the Pilbara region 9 Population size 9 Population growth 13 Population distribution 14 Age composition 16 Population projections 18 3. -

Argument Coding and Clause Linkage in Australian Aboriginal Languages

Argument coding and clause linkage in Australian Aboriginal languages Peter K. Austin Department of Linguistics SOAS, University of London [email protected] 2017-11-08 © Peter K. Austin 1. Introduction1 In the descriptive and typological linguistic literature, Australian Aboriginal languages, especially those of the Pama-Nyungan group, have become notorious for their complex systems of case marking, showing such characteristics as split-ergative morphological coding (Silverstein 1976, Dixon 1979, 1980, 1994, Blake 1977 etc.), interactions of marking with animacy (Aristar 1997, Bickel 2008, Simpson 2012, Verstraete 2010, Filimonova 2005), multiple levels of case marking (‘case stacking’) (Dench and Evans 1988, Simpson 1991, Planck 1996, Andrews 1996, Nordlinger 1998, Austin 1995), and case affixation on verbs (Dench and Evans 1988, Blake 199?). The focus of this paper is argument encoding in linked, typically non-finite, clauses in a range of languages to explore the ways in which predicate-argument grammatical functions are encoded in such constructions cross-linguistically within Australia. I will draw on data from a range of languages, primarily from the Pama-Nyungan group, but also including some non- Pama-Nyungan materials. The aim is to develop a descriptively adequate typology of argument encoding in linked clauses which can serve as a basis for further theoretical and historical research (but see Nordlinger 1998, Dench 1994, Evans 1995).2 1 The major issues discussed in this paper have been the subject of on-going research over the past 35 years, arising from my attempts to understand the morpho-syntax of languages of the Gascoyne-Ashburton region of Western Australia (see Austin 1981b, 1988, 1995). -

Pama-Nyungan), in Comparison with Two Neighbouring Languages

Language Documentation and Description ISSN 1740-6234 ___________________________________________ This article appears in: Language Documentation and Description, vol 10: Special Issue on Humanities of the lesser-known: New directions in the description, documentation and typology of endangered languages and musics. Editors: Niclas Burenhult, Arthur Holmer, Anastasia Karlsson, Håkan Lundström & Jan-Olof Svantesson Main clause TAM-marking in Ngarla (Pama-Nyungan), in comparison with two neighbouring languages TORBJÖRN WESTERLUND Cite this article: Torbjörn Westerlund (2012). Main clause TAM-marking in Ngarla (Pama-Nyungan), in comparison with two neighbouring languages. In Niclas Burenhult, Arthur Holmer, Anastasia Karlsson, Håkan Lundström & Jan- Olof Svantesson (eds) Language Documentation and Description, vol 10: Special Issue on Humanities of the lesser-known: New directions in the description, documentation and typology of endangered languages and musics. London: SOAS. pp. 228-246 Link to this article: http://www.elpublishing.org/PID/120 This electronic version first published: July 2014 __________________________________________________ This article is published under a Creative Commons License CC-BY-NC (Attribution-NonCommercial). The licence permits users to use, reproduce, disseminate or display the article provided that the author is attributed as the original creator and that the reuse is restricted to non-commercial purposes i.e. research or educational use. See http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ ______________________________________________________