Lightweight Automotive Diesel Engine Concepts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mean Value Modelling of a Poppet Valve EGR-System

Mean value modelling of a poppet valve EGR-system Master’s thesis performed in Vehicular Systems by Claes Ericson Reg nr: LiTH-ISY-EX-3543-2004 14th June 2004 Mean value modelling of a poppet valve EGR-system Master’s thesis performed in Vehicular Systems, Dept. of Electrical Engineering at Linkopings¨ universitet by Claes Ericson Reg nr: LiTH-ISY-EX-3543-2004 Supervisor: Jesper Ritzen,´ M.Sc. Scania CV AB Mattias Nyberg, Ph.D. Scania CV AB Johan Wahlstrom,¨ M.Sc. Linkopings¨ universitet Examiner: Associate Professor Lars Eriksson Linkopings¨ universitet Linkoping,¨ 14th June 2004 Avdelning, Institution Datum Division, Department Date Vehicular Systems, Dept. of Electrical Engineering 14th June 2004 581 83 Linkoping¨ Sprak˚ Rapporttyp ISBN Language Report category — ¤ Svenska/Swedish ¤ Licentiatavhandling ISRN ¤ Engelska/English ££ ¤ Examensarbete LITH-ISY-EX-3543-2004 ¤ C-uppsats Serietitel och serienummer ISSN ¤ D-uppsats Title of series, numbering — ¤ ¤ Ovrig¨ rapport ¤ URL for¨ elektronisk version http://www.vehicular.isy.liu.se http://www.ep.liu.se/exjobb/isy/2004/3543/ Titel Medelvardesmodellering¨ av EGR-system med tallriksventil Title Mean value modelling of a poppet valve EGR-system Forfattare¨ Claes Ericson Author Sammanfattning Abstract Because of new emission and on board diagnostics legislations, heavy truck manufacturers are facing new challenges when it comes to improving the en- gines and the control software. Accurate and real time executable engine models are essential in this work. One successful way of lowering the NOx emissions is to use Exhaust Gas Recirculation (EGR). The objective of this thesis is to create a mean value model for Scania’s next generation EGR system consisting of a poppet valve and a two stage cooler. -

Engine Block Materials and Its Production Processes

ENGINE BLOCK MATERIALS AND ITS PRODUCTION PROCESSES 2.2 THE CAST IRON MONOLITHIC BLOCK The widespread use of cast iron monolithic block is as a result of its low cost and its formidability. This type of block normally comes as the integral type where the engine cylinder and the upper crankcase are joined together as one. The iron used for this block is the gray cast iron having a pearlite-microstructure. The iron is called gray cast iron because its fracture has a gray appearance. Ferrite in the microstructure of the bore wall should be avoided because too much soft ferrite tends to cause scratching, thus increasing blow-by. The production of cast iron blocks using a steel die is rear because its lifecycle is shortened as a result of the repeated heat cycles caused by the molten iron. Sand casting is the method widely used in the production of cast iron blocks. This involves making the mould for the cast iron block with sand. The preparation of sand and the bonding are a critical and very often rate-controlling step. Permanent patterns are used to make sand molds. Usually, an automated molding machine installs the patterns and prepares many molds in the same shape. Molten metal is poured immediately into the mold, giving this process very high productivity. After solidification, the mold is destroyed and the inner sand is shaken out of the block. The sand is then reusable. The bonding of sand is done using two main methods: (i) the green sand mold and (ii) the dry sand mold. -

Section 02 - Block Basics

Block Basics – Section 2 Section 02 - Block Basics 2.0 Small Block 330 & 350 Block Key Differences. The key differences between the 330 and 350 are the 350’s larger bore and the Generation 1 Cast Iron Small Block V-8 Facts 330’s forged crank. General. In 1964 Olds replaced their small block 215 V8 with 1964 – 1966 Valve Lifter Angle. All 1964–1966 blocks used a a cast iron block of completely new design. The 330 V-8 different valve lifter angle of attack on the cam (45). Thus shared none of its engine block architecture with that of the 1964–1966 330 blocks CANNOT USE 1967 AND LATER 215 V-8 and the 225 V-6 sourced from Buick. The engine CAMS. All 1964–1966 cams WILL NOT WORK in 1967 and was no longer aluminum, but cast iron, as weight became later blocks. Later blocks used a 39 lifter angle. Blocks with less of a factor with the engine going into both the larger a “1” or “1A” cast up near the oil filler tube used the 45 lifter mid-sized F-85s, Cutlasses and the full-size Jetstars angle and should be avoided, if possible. introduced in that year. The engine was designed as a replacement for the 215, but was cast iron and enlarged in Early 330 Rocker Arms. The first run of 330 blocks was anticipation of the growth in size of the mid-size cars, where equipped with rocker arms similar to the previous 394 block it was to be primarily used and as the workhorse for the that traces its heritage back to 1949. -

United States Patent (19) 11 Patent Number: 5,950,587 Sattler Et Al

USOO5950587A United States Patent (19) 11 Patent Number: 5,950,587 Sattler et al. (45) Date of Patent: Sep. 14, 1999 54 CONTINUOUSLY WARIABLE RUNNER 2682431-A1 4/1993 France. LENGTH MANIFOLD 3825000 A1 2/1989 Germany .......................... 123/184.55 60-224923 11/1985 Japan .................... ... 123/184.55 75 Inventors: Eric R. Sattler, Trenton; Joel S. 2239899 7/1991 United Kingdom ...... ... 123/184.55 Myers, Southgate; Michael J. Haspel, Westland, all of Mich. Primary Examiner Erick R. Solis 73 Assignee: BASF Corporation, Mount Olive, N.J. ASSistant Examiner Brian Hairston Attorney, Agent, or Firm-Ryan W. Massey; James J. Drake 22 Filed: Jul. 22, 1998 A continuously variable runner length manifold is provided (51) Int. Cl. ................................................ FO2B 27/06 for an internal combustion engine. The continuously vari 52 U.S. Cl. .................. 123/184.55; 123/18453 able runner length manifold includes a housing having an 58 Field of Search ........................... 123/184.55, 18453 inlet port and a plurality of outlet ports defined by a plurality of Stacked manifold Sections. A plurality of runner members 56) References Cited are rotatably mounted within the housing. The runner mem bers include wall portions which combine with the housing U.S. PATENT DOCUMENTS to define a plurality of runners in communication with a 4,619,226 10/1986 Ueda et al. ........................ 123s2 MB plenum and a respective one of the outlet ports. The runners 4,699,630 10/1987 Lee et al. ............................... 48/1801 have a length which is continuously variable upon rotation of the runner members relative to the housing. FOREIGN PATENT DOCUMENTS 237755 A2 9/1987 European Pat. -

Compacted Graphite Iron for Diesel Engine Cylinder Blocks

Compacted Graphite Iron for Diesel Engine Cylinder Blocks Wilson Luiz Guesser, Dr Eng - Tupy Fundições and UDESC - Joinville, SC – Brazil – [email protected] Pedro Ventrela Duran, M Sc - Tupy Fundições - Joinville, SC – Brazil – [email protected] Walmor Krause, M Sc - Tupy Fundições - Joinville, SC – Brazil – [email protected] Abstract The recent trends in diesel engines are discussed, and also the consequences in materials selection for engine cylinder blocks. The increasing demand for higher specific power and the need for weight reduction and decrease of emissions require the use of stronger materials for cylinder blocks, opening a promising space for compacted graphite iron (CGI). The properties of CGI are described, in particular those required for engine cylinder blocks (fatigue strength and elastic modulus). Results of mechanical properties from actual castings are presented. As a result of the mechanical properties improvement, some design opportunities are suggested, in order to decrease the weight of the cylinder block. Keywords diesel engines, compacted graphite iron, cylinder blocks 1. Introduction: In a recent paper discussing CGI uses for engine cylinder blocks and heads, S. Dawson (2001) stated that “the Iron Age is just beginning” and we have taken this statement for the present paper. His point of view, added to those from Rizzo (2001), discloses the enormous CGI potential for manufacturing engine components, especially for diesel engines. The growth of diesel engines usage for passenger cars has been remarkable in Europe (see Fig. 1), especially after the introduction of the high-pressure common-rail technology (Buchholz, 2003). This growth is surrounded by requirements as: less fuel consumption, emissions reduction , larger power output and torque, and for passenger cars more compact engines are being required due to space limitations. -

GM Engine Block

A Design Study in Aluminum Casting Aluminum Cylinder Block for General Motors Truck/SUV Engines Design Study Outline -- Introduction -- Designing for Performance Alloy Selection -- Lost Foam Casting Pattern Design Pattern Production Chevy Trailblazer Metal Casting -- Finishing and Quality Assurance -- Lessons Learned and Summary Start the Design Study ! Next Acknowledgment -- The metalcasting design studies are a joint effort of the American Foundry Society and the Steel Founders' Society of America. Project funding was provided by the American Metalcasting Consortium Project, which is sponsored by the Defense Logistics Agency, Attn: DLSC-T, Ft. Belvoir, VA, 22060-6221 Copyright 2004 by the American Foundry Society In cooperation with All rights reserved. GM Powertrain Casting Address comments to: [email protected] Return to AFS Last Modified:August, 2004 by STG Development Home Page A Design Study in Aluminum Castings - GM Cylinder Block Engines for GM SUVs and Trucks The Application -- In 2002 General Motors introduced a new family of Sport Utility Vehicles (Chevy Trailblazer, Buick Rainier and GMC Envoy). In 2004 a family of mid-sized trucks (Chevy Colorado and GMC Canyon) was introduced. ● With the higher vehicle weight and additional load capability, the engineering challenge was to upgrade the powertrain with improvements in power, torque, fuel economy, emissions, and NVH (noise, vibration, harshness ) performance, while keeping the vehicle cost affordable and the weight down. ● A comprehensive engineering study was done to select the best engine configuration, considering V-8, V-6, and Inline 6 designs. The study determined that the Inline design had the following advantages -- simplest design, lowest number of parts, inherently balanced, lowest cost, and best manufacturing flexibility. -

Variable Valve Trains

VARIABLE VALVE TRAINS THE EVOLVING ENGINE Pierburg GmbH Alfred-Pierburg-Straße 1 41460 Neuss Germany www.kspg.com “We’re WORKING ON TOMORROW’s DOUBLY COMPLEMEntaRY AUTOMOBILE ENGINE.” 4-5 UniValve and FlexValve Dr. Dirk Hunkel, Director Business Unit Variable Valve Train Systems, Pierburg GmbH PRECISION FOR HIGH RPM 6-7 UniValve – Design and Function Gasoline or diesel? For years, these arch- inside the combustion chamber while BOTH ROBUst AND VERsatILE 8-9 rivals have charged ahead along their keeping the impact on the fuel con- FlexValve – Design and Function independent respective development sumption to a minimum. The fact that paths, each chiding the other with its variability in the air handling system 715/2007/EG 10 -11 own technical advances. Each system provides advantages for both engines is You want to see it in black and white? has its strengths, but also its weakness- undisputed. But variable valve trains es. The stoichiometric gasoline engine offer even more potential. Keywords are THE EVOLUTION OF YOUR ENGINE 12-13 features a highly efficient and cost displacement on demand, scavenging We work with you to produce a bespoke design. effective after-treatment system thanks and engine braking. to its three-way catalytic converter. But “VaRIABLE VALVE TRAIN SYstEMS ARE NOT 14-17 the fuel consumption has to be im- We’d like to show you what variable SOMETHING YOU JUst GET OFF THE SHELF.” proved. Diesel engines, on the other valve train systems can do. And we’d An interview with Heinrich Dismon, CTO hand, have already reached a very high like to assist you with your decision, efficiency. -

Rebuilding Your First Engine by Joe Mondello

REBUILDING YOUR FIRST ENGINE BY JOE MONDELLO Rebuilding an engine is involved, particular steps must be taken and confidence in the professionalism of your machinist is most important. The first thing is to research the exact cubic inch displacement, year, and type of engine that is in your car. Our technical reference manual will be a great help to you when rebuilding your engine. Always take photos of the engine and engine compartment. Pay special attention to brackets, accessory head bolts, wire looms, AC hoses, belts and special headed or stud type-mounting bolts. Before starting to remove your engine, cover the fenders, front grill and sheet metal with good fender covers or heavy blankets. Then disconnect the battery, fuel lines and drain all the fluids. You should remove the radiator first remembering to disconnect radiator hoses and transmission oil cooler lines to eliminate a big mess of dripping transmission fluid. The carburetor and distributor should then be removed. Connect a chain, engine cradle stop or carburetor plate adapter to engine and prepare to remove the engine. Disconnect engine and transmission mounts and remove the hood. Scribe or use a marking pen around the mounting brackets so hood replacement will be easier. Sometimes the removal of the rear transmission crossover-mounting bar will allow more of a tilt for easier engine and transmission removal. Always block the rear wheels so the car cannot move fore and aft. Always make sure your engine hoist and removing device is securely bolted down and is tight. If you have a 4-speed car, disconnect the clutch cross shaft and all the linkage. -

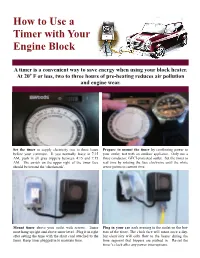

How to Use a Timer with Your Engine Block

How to Use a Timer with Your Engine Block A timer is a convenient way to save energy when using your block heater. At 20o F or less, two to three hours of pre-heating reduces air pollution and engine wear. Set the timer to supply electricity two to three hours Prepare to mount the timer by confirming power to before your commute. It you normally leave at 7:15 your outlet; test with an outdoor appliance. Only use a AM, push in all gray trippers between 4:15 and 7:15 three conductor, GFCI-protected outlet. Set the timer to AM. The switch on the upper right of the timer face real time by rotating the face clockwise until the white should be toward the ‘checkmark’. arrow points to current time. Mount timer above your outlet with screws. Timer Plug in your car each evening to the outlet on the bot- must hang upright and above snow level. Plug it in right tom of the timer. The clock face will rotate once a day, after setting the time with the short cord attached to the but electricity will only flow to the heater during the timer. Keep timer plugged in to maintain time. time segment that trippers are pushed in. Re-set the timer’s clock after any power interruptions. During a typical morning commute more pollution is created by vehicles idling in driveways than driving on roadways. Block heaters reduce these emissions by warming engine compo- nents, allowing emission controls to work sooner. Vehicle emissions testing performed in Anchorage and Fairbanks proved that block heater use substantially reduces carbon monoxide (CO) and other pollu- tion from cold engines. -

Piston Engine Fundamentals TC010-05-01S

LEVEL F PPiissttoonn EEnnggiinnee FFuunnddaammeennttaallss TTCC001100--0055--0011SS Mazda Motor Corporation Technical Service Training Piston Engine Fundamentals CONTENTS TC010-05-01S 1 – INTRODUCTION ............................................................................1 Course Overview ..................................................................................1 Audience and Purpose...................................................................1 Course Content and Objectives .................................................2 How to Use This Guide .........................................................................3 Section Objectives .........................................................................3 Text and Illustrations......................................................................3 Review Exercises ..........................................................................4 2 – BASIC OPERATION.......................................................................5 Objectives .............................................................................................5 How Power is Developed......................................................................6 Harnessing Power..........................................................................6 Controlling Combustion..................................................................7 The Four-Stroke Cycle..........................................................................9 Intake Stroke............................................................................... -

A Numerical Investigation of a Two-Stroke Poppet-Valved Diesel Engine Concept

A NUMERICAL INVESTIGATION OF A TWO-STROKE POPPET-VALVED DIESEL ENGINE CONCEPT Philip Robert Teakle BE MEngSc Tribology and Materials Technology Group Mechanical, Manufacturing and Medical Engineering Queensland University of Technology Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2004 v Keywords Two-stroke, poppet valves, KIVA, thermodynamic modelling, zero-dimensional modelling, multidimensional modelling, engine modelling, scavenging models, scavenging simulations. Executive Summary Two-stroke poppet-valved engines may combine the high power density of two - stroke engines and the low emissions of poppet-valved engines. A two-stroke diesel engine can generate the same power as a four-stroke engine of the same size, but at higher (leaner) air/fuel ratios. Diesel combustion at high air/fuel ratios generally means hydrocarbons, soot and carbon monoxide are oxidised more completely to water and carbon dioxide in the cylinder, and the opportunity to increase the rate of exhaust gas recirculation should reduce the formation of nitrogen oxides (NOx). The concept is being explored as a means of economically modifying diesel engines to make them cleaner and/or more powerful. This study details the application of two computational models to this problem. The first model is a relatively simple thermodynamic model created by the author capable of rapidly estimating the behaviour of entire engine systems. It was used to estimate near-optimum engine system parameters at single engine operating points and over a six-mode engine cycle. The second model is a detailed CFD model called KIVA- ERC. It is a hybrid of the KIVA engine modelling package developed at the Los Alamos National Laboratory and combustion and emissions subroutines developed at the University of Wisconsin-Madison Engine Research Center. -

The Dilemma Between Aluminum and Cast Iron

energies Article Life-Cycle and Energy Assessment of Automotive Component Manufacturing: The Dilemma Between Aluminum and Cast Iron Konstantinos Salonitis , Mark Jolly * , Emanuele Pagone and Michail Papanikolaou Manufacturing Theme, Cranfield University, Cranfield, Bedford, MK43 0AL, UK * Correspondence: m.r.jolly@cranfield.ac.uk; Tel.: +44 (0)1234 758347 Received: 6 June 2019; Accepted: 30 June 2019; Published: 3 July 2019 Abstract: Considering the manufacturing of automotive components, there exists a dilemma around the substitution of traditional cast iron (CI) with lighter metals. Currently, aluminum alloys, being lighter compared to traditional materials, are considered as a more environmentally friendly solution. However, the energy required for the extraction of the primary materials and manufacturing of components is usually not taken into account in this debate. In this study, an extensive literature review was performed to estimate the overall energy required for the manufacturing of an engine cylinder block using (a) cast iron and (b) aluminum alloys. Moreover, data from over 100 automotive companies, ranging from mining companies to consultancy firms, were collected in order to support the soundness of this investigation. The environmental impact of the manufacturing of engine blocks made of these materials is presented with respect to the energy burden; the “cradle-to-grave approach” was implemented to take into account the energy input of each stage of the component life cycle starting from the resource extraction and reaching to the end-of-life processing stage. Our results indicate that, although aluminum components contribute toward reduced fuel consumption during their use phase, the vehicle distance needed to be covered in order to compensate for the up-front energy consumption related to the primary material production and manufacturing phases is very high.