Beezley Hills Field Trip Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Washington Division of Geology and Earth Resources Open File Report

RECONNAISSANCE SURFICIAL GEOLOGIC MAPPING OF THE LATE CENOZOIC SEDIMENTS OF THE COLUMBIA BASIN, WASHINGTON by James G. Rigby and Kurt Othberg with contributions from Newell Campbell Larry Hanson Eugene Kiver Dale Stradling Gary Webster Open File Report 79-3 September 1979 State of Washington Department of Natural Resources Division of Geology and Earth Resources Olympia, Washington CONTENTS Introduction Objectives Study Area Regional Setting 1 Mapping Procedure 4 Sample Collection 8 Description of Map Units 8 Pre-Miocene Rocks 8 Columbia River Basalt, Yakima Basalt Subgroup 9 Ellensburg Formation 9 Gravels of the Ancestral Columbia River 13 Ringold Formation 15 Thorp Gravel 17 Gravel of Terrace Remnants 19 Tieton Andesite 23 Palouse Formation and Other Loess Deposits 23 Glacial Deposits 25 Catastrophic Flood Deposits 28 Background and previous work 30 Description and interpretation of flood deposits 35 Distinctive geomorphic features 38 Terraces and other features of undetermined origin 40 Post-Pleistocene Deposits 43 Landslide Deposits 44 Alluvium 45 Alluvial Fan Deposits 45 Older Alluvial Fan Deposits 45 Colluvium 46 Sand Dunes 46 Mirna Mounds and Other Periglacial(?) Patterned Ground 47 Structural Geology 48 Southwest Quadrant 48 Toppenish Ridge 49 Ah tanum Ridge 52 Horse Heaven Hills 52 East Selah Fault 53 Northern Saddle Mountains and Smyrna Bench 54 Selah Butte Area 57 Miscellaneous Areas 58 Northwest Quadrant 58 Kittitas Valley 58 Beebe Terrace Disturbance 59 Winesap Lineament 60 Northeast Quadrant 60 Southeast Quadrant 61 Recommendations 62 Stratigraphy 62 Structure 63 Summary 64 References Cited 66 Appendix A - Tephrochronology and identification of collected datable materials 82 Appendix B - Description of field mapping units 88 Northeast Quadrant 89 Northwest Quadrant 90 Southwest Quadrant 91 Southeast Quadrant 92 ii ILLUSTRATIONS Figure 1. -

Periodically Spaced Anticlines of the Columbia Plateau

Geological Society of America Special Paper 239 1989 Periodically spaced anticlines of the Columbia Plateau Thomas R. Watters Center for Earth and Planetary Studies, National Air and Space Museum, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D. C. 20560 ABSTRACT Deformation of the continental flood-basalt in the westernmost portion of the Columbia Plateau has resulted in regularly spaced anticlinal ridges. The periodic nature of the anticlines is characterized by dividing the Yakima fold belt into three domains on the basis of spacings and orientations: (1) the northern domain, made up of the eastern segments of Umtanum Ridge, the Saddle Mountains, and the Frenchman Hills; (2) the central domain, made up of segments of Rattlesnake Ridge, the eastern segments of Horse Heaven Hills, Yakima Ridge, the western segments of Umtanum Ridge, Cleman Mountain, Bethel Ridge, and Manastash Ridge; and (3) the southern domain, made up of Gordon Ridge, the Columbia Hills, the western segment of Horse Heaven Hills, Toppenish Ridge, and Ahtanum Ridge. The northern, central, and southern domains have mean spacings of 19.6,11.6, and 27.6 km, respectively, with a total range of 4 to 36 km and a mean of 20.4 km (n = 203). The basalts are modeled as a multilayer of thin linear elastic plates with frictionless contacts, resting on a mechanically weak elastic substrate of finite thickness, that has buckled at a critical wavelength of folding. Free slip between layers is assumed, based on the presence of thin sedimentary interbeds in the Grande Ronde Basalt separating groups of flows with an average thickness of roughly 280 m. -

Top 26 Trails in Grant County 2020

and 12 Watchable Wildlife Units For more information, please contact: Grant County Tourism Commission P.O. Box 37, Ephrata, WA 98823 509.765.7888 • 800.992.6234 In Grant County, Washington TourGrantCounty.com TOP TRAILS Grant County has some of the most scenic and pristine vistas, hiking trails and outdoor 26 recreational opportunities in Washington State. and 12 Watchable Wildlife Units Grant County is known for its varied landscapes on a high desert plateau with coulees, lakes, in Grant County Washington reservoirs, sand dunes, canals, rivers, creeks, and other waterways. These diverse ecosystems Grant County Tourism Commission For Additional copies please contact: support a remarkable variety of fish and PO Box 37 Jerry T. Gingrich wildlife species that contribute to the economic, Ephrata, Washington 98837 Grant County Tourism Commission recreational and cultural life of the County. www.tourgrantcounty.com Grant County Courthouse PO Box 37 Ephrata, WA 98837 No part of this book may be reproduced in (509) 754-2011, Ext. 2931 any form, or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, without permission in For more information on writing from the Grant County Tourism Grant County accommodations Commission. www.tourgrantcounty.com © 2019, Grant County Tourism Commission Second printing, 10m Trails copy and photographs Book, map and cover design by: provided by: Denise Adam Graphic Design Cameron Smith, Lisa Laughlin, J. Kemble, Veradale, WA 99037 Shawn Cardwell, Mark Amara, (509) 891-0873 Emry Dinman, Harley Price, [email protected] Sebastian Moraga and Madison White Printed by: Rewriting and editing by: Mark Amara Pressworks 2717 N. Perry Street Watchable Wildlife copy and Spokane, Washington 99207 photographs provided by: (509) 462-7627 Washington Department of [email protected] Fish and Wildlife Photograph by Lisa Laughlin CONTENTS CONTENTS Grant County Trails and Hiking Grant County Watchable Wildlife Viewing Upper Grand Coulee Area 1. -

COULEE CORRIDOR Scenic Byway

COULEE CORRIDOR SCENIC BYWAY INDEX Sites Page Sites Page INFO KEY 1 1 Corfu Woods and Lower 2 28 Audubon Kiosk Overlook 7 Crab Creek 29 Rocky Ford Creek 2 Royal Lake Overlook 30 Oasis Park 3 Drumheller Overlook 31 Martin Road Russian-Olives 4 Crab Creek Access 32 Norton Road Shrub-Steppe 5 McManamon Lake 33 Jameson Lake 6 Frog Lake, Crab Creek 3 34 Eastern Douglas County 8 and Marsh Trails 35 SW Banks Lake/Ankeny Access 7 Unit 1 Marsh Overlook 36 Dry Falls Overlook 8 Soda and Migraine Lakes 37 Sun Lakes State Park 9 Pillar Wigeon Lakes Area 38 Blue Lake Rest Area 10 Lind Coulee Overview 39 Lake Lenore 9 11 O’Sullivan Dam 4 40 West Beach Park 12 Potholes State Park 41 Gloyd Seeps 13 Desert Wildlife Area - Road 42 Brook Lake C SE 43 Crab Lake/Wilson Creek 14 Birder’s Corner 15 Desert Wildlife Area – Road 44 Old Coulee Highway 10 ‘I’ SW Route 16 Beda Lake 45 Crescent Bay Lake 46 Fiddle Creek 17 Dodson Road - 5 47 Barker Canyon Winchester Wasteway 48 North Dam Park 18 Audubon Dodson Road 49 Osborn Bay Campground Nature Trail 19 Crab Creek Overlook 50 Northrup Point Access 11 20 Potholes Reservoir Peninsula 51 Northrup Canyon Overlook 52 Steamboat Rock Peninsula 53 Coulee City Community Park 21 North Potholes Reserve/ 6 Job Corps Dike 54 Sinlahekin Wildlife Area 12 22 Moses Lake Community Park 23 Moses Lake Outlets CREDITS 12 24 Snowy Owl Route 25 Montlake Park 26 Three Ponds Loggerhead Shrike © Ed Newbold, 2003 27 Neppel Landing Park The Great Washington State Birding Trail 1 COULEE CORRIDOR INFO KEY MAp Icons Best seasons for birding (spring, summer, fall, winter) Developed camping available, including restrooms; fee required Restroom available at day-use site Handicapped restroom and handicapped trail or viewing access Site located in an Important Bird Area Fee required. -

Eastern Washington Pheasant Enhancement Program Annual Report Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife

State of Washington DEPARTMENT OF FISH AND WILDLIFE Mailing Address: P.O. Box 43200, Olympia, WA 98504-3200 • (360) 902-2200 • TDD (360) 902-2207 Main Office Location: Natural Resources Building, 1111 Washington Street SE, Olympia, WA November 10, 2020 The Honorable Christine Rolfes The Honorable Timm Ormsby Chair, Senate Ways and Means Chair, House Appropriations 303 John A. Cherberg Building 315 John L. O’Brien Building Post Office Box 40466 Post Office Box 40600 Olympia, WA 98504-0466 Olympia, WA 98504-0600 The Honorable Kevin Van De Wege The Honorable Brian Blake Chair, Senate Agriculture, Water Chair, House Rural Development, Natural Resources, and Parks Agriculture & Natural Resources 212 John A. Cherberg Building 437A Legislative Building Post Office Box 40424 Post Office Box 40600 Olympia, Olympia, WA 98504 WA 98504 Dear Chairpersons Rolfes, Ormsby, Van De Wege, and Blake: I am writing to provide you with the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife’s (Department) annual report regarding the Eastern Washington Pheasant Enhancement Program (EWPEP). The Department is required to submit an annual report (per RCW 77.12.820) summarizing the Department’s eastern Washington pheasant activities under the program. Pheasant harvest has declined in Eastern Washington over the past two decades. To address hunting success rates and pheasant habitat loss, the Department created the EWPEP. The EWPEP completes habitat enhancement to benefit wild pheasant populations and targets the decline by releasing adult rooster pheasants on public lands. The Washington State Legislature funded the EWPEP in 1997 with a dedicated account called the Eastern Washington Pheasant Enhancement account. The funding is derived from a portion of small game hunting licenses, based on the proportion of purchasers who hunt pheasants in eastern Washington. -

A G~Ographic Dictionary of Washington

' ' ., • I ,•,, ... I II•''• -. .. ' . '' . ... .; - . .II. • ~ ~ ,..,..\f •• ... • - WASHINGTON GEOLOGICAL SURVEY HENRY LANDES, State Geologist BULLETIN No. 17 A G~ographic Dictionary of Washington By HENRY LANDES OLYMPIA FRAN K M, LAMBORN ~PUBLIC PRINTER 1917 BOARD OF GEOLOGICAL SURVEY. Governor ERNEST LISTER, Chairman. Lieutenant Governor Louis F. HART. State Treasurer W.W. SHERMAN, Secretary. President HENRY SuzzALLO. President ERNEST 0. HOLLAND. HENRY LANDES, State Geologist. LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL. Go,:ernor Ernest Lister, Chairman, and Members of the Board of Geological Survey: GENTLEMEN : I have the honor to submit herewith a report entitled "A Geographic Dictionary of Washington," with the recommendation that it be printed as Bulletin No. 17 of the Sun-ey reports. Very respectfully, HENRY LAKDES, State Geologist. University Station, Seattle, December 1, 1917. TABLE OF CONTENTS. Page CHAPTER I. GENERAL INFORMATION............................. 7 I Location and Area................................... .. ... .. 7 Topography ... .... : . 8 Olympic Mountains . 8 Willapa Hills . • . 9 Puget Sound Basin. 10 Cascade Mountains . 11 Okanogan Highlands ................................ : ....' . 13 Columbia Plateau . 13 Blue Mountains ..................................... , . 15 Selkirk Mountains ......... : . : ... : .. : . 15 Clhnate . 16 Temperature ......... .' . .. 16 Rainfall . 19 United States Weather Bureau Stations....................... 38 Drainage . 38 Stream Gaging Stations. 42 Gradient of Columbia River. 44 Summary of Discharge -

Dr. Brett R. Lenz

COLONIZER GEOARCHAEOLOGY OF THE PACIFIC NORTHWEST REGION A Dissertation DR. BRETT R. LENZ COLONIZER GEOARCHAEOLOGY OF THE PACIFIC NORTHWEST REGION, NORTH AMERICA Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Leicester By Brett Reinhold Lenz Department of Archaeology and Ancient History University of Leicester June 2011 1 DEDICATION This work is dedicated to Garreck, Haydn and Carver. And to Hank, for teaching me how rivers form. 2 Abstract This dissertation involves the development of a geologic framework applied to upper Pleistocene and earliest Holocene archaeological site discovery. It is argued that efforts to identify colonizer archaeological sites require knowledge of geologic processes, Quaternary stratigraphic detail and an understanding of basic soil science principles. An overview of Quaternary geologic deposits based on previous work in the region is presented. This is augmented by original research which presents a new, proposed regional pedostratigraphic framework, a new source of lithic raw material, the Beezley chalcedony, and details of a new cache of lithic tools with Paleoindian affinities made from this previously undescribed stone source. 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The list of people who deserve my thanks and appreciation is large. First, to my parents and family, I give the greatest thanks for providing encouragement and support across many years. Without your steady support it would not be possible. Thanks Mom and Dad, Steph, Jen and Mellissa. To Dani and my sons, I appreciate your patience and support and for your love and encouragement that is always there. Due to a variety of factors, but mostly my own foibles, the research leading to this dissertation has taken place over a protracted period of time, and as a result, different stages of my personal development are likely reflected in it. -

Top 35 Fishing Waters of Grant County

TOP35 FISHING WATERS In Grant County, Washington For more information, please contact: Grant County Tourism Commission P.O. Box 37, Ephrata, WA 98823 509.765.7888 • 800.992.6234 TourGrantCounty.com CONTENTS Grant County Tourism Commission The Top 35 Fishing Waters In Grant County, Washington PO Box 37 1. Potholes Reservoir (28,000 acres) .................................................1 Ephrata, Washington 98837 2. Banks Lake (24,900 acres) .......................................................2 TOP 3. Moses Lake (6,800 acres) .......................................................3 No part of this book may be reproduced in any 4. Blue Lake (534 acres) ...........................................................4 3 form, or by any electronic, mechanical, or other 5. Park Lake (338 acres) ...........................................................5 5 means, without permission in writing from the 6. Burke Lake (69 acres) ...........................................................6 Grant County Tourism Commission. 7. Martha Lake (15 acres) ..........................................................7 FISHING 8. Corral Lake (70 acres) ...........................................................8 © 2019, Grant County Tourism Commission Fifth printing, 10m 9. Priest Lake Pool (below Wanapum Dam) ...........................................8 WATERS 10. Hanford Reach (below Priest Rapids Dam) .........................................10 11. Rocky Ford Creek .............................................................11 In Grant County, Washington -

Splay-Fault Origin for the Yakima Fold-And-Thrust Belt, Washington State 2 3 Thomas L

1 Splay-fault origin for the Yakima fold-and-thrust belt, Washington State 2 3 Thomas L. Pratt, United States Geological Survey, School of Oceanography, Box 357940, 4 University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98115 5 6 ABSTRACT 7 The Yakima fold-and-thrust belt (YFTB) is a set of anticlines above reverse faults in the 8 Miocene Columbia River Basalt (CRB) flows of Washington State. The YFTB is bisected by the 9 ~1100-km-long Olympic-Wallowa geomorphic lineament (OWL). There is considerable debate 10 about the origin and earthquake potential of the YFTB and OWL, which lie near six major dams 11 and a large nuclear waste storage site. Here I show that the trends of the YFTB anticlines relative 12 to the OWL match remarkably well the trends of the principal stresses determined from Linear 13 Elastic Fracture Mechanics (LEFM) modeling of the end of a vertical strike-slip fault. From this 14 comparison and the termination of some YFTB anticlines at the OWL, I argue that the YFTB 15 formed as splay faults caused by an abrupt decrease in the amount of strike-slip motion along the 16 OWL. If this hypothesis is correct, the OWL and YFTB are likely interconnected, deeply-rooted 17 structures capable of large earthquakes. 18 19 20 INTRODUCTION 21 The Yakima fold and thrust belt (YFTB) of central Washington State is a set of 22 prominent anticlines in the Miocene Columbia River Basalt flows (CRB; figure 1). The YFTB 23 anticlines form three distinct sets (Riedel et al., 1989 and 1994; Watters, 1989). -

Crab Creek Alternate Water Supply Route Study: Water Quality Monitoring

Quality Assurance Project Plan Crab Creek Alternate Water Supply Route Study: Water Quality Monitoring July 2009 Publication No. 09-03-116 Publication Information This plan is available on the Department of Ecology’s website at www.ecy.wa.gov/biblio/0903116.html. Data for this project will be available on Ecology’s Environmental Information Management (EIM) website at www.ecy.wa.gov/eim/index.htm. Search User Study ID, jros0011 Ecology’s Project Tracker Code for this study is 09-250. Waterbody Numbers: WA-41-1030, WA-42-1010 Author and Contact Information Jim Ross Environmental Assessment Program Eastern Regional Office Washington State Department of Ecology Spokane, WA 99205-1295 For more information contact: Carol Norsen Communications Consultant Environmental Assessment Program P.O. Box 47600 Olympia, WA 98504-7600 Phone: 360-407-7486 Washington State Department of Ecology - www.ecy.wa.gov/ o Headquarters, Olympia 360-407-6000 o Northwest Regional Office, Bellevue 425-649-7000 o Southwest Regional Office, Olympia 360-407-6300 o Central Regional Office, Yakima 509-575-2490 o Eastern Regional Office, Spokane 509-329-3400 Any use of product or firm names in this publication is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the author or the Department of Ecology. To ask about the availability of this document in a format for the visually impaired, call Carol Norsen at 360-407-7486. Persons with hearing loss can call 711 for Washington Relay Service. Persons with a speech disability can call 877- 833-6341. Quality Assurance -

2021 Warmwater Fishing Opportunities in Central Washington

2021 Warmwater Fishing opportunities in Central Washington Table of Contents Washington’s Warmwater Fish Program ..................................................................................................................... 1 Fish Washington Mobile app ...................................................................................................................................... 1 Region Two Warmwater Team Duties ........................................................................................................................ 2 Summary of Regional Warmwater Activities in 2020-21 .............................................................................................. 3 Walleye Surveys (FWIN) ........................................................................................................................................... 3 Adams County........................................................................................................................................................... 4 Cow Lake (Largemouth Bass, Bluegill, Brown Bullhead, and Rainbow Trout emphasis) ........................................................................... 4 Hutchinson—Shiner Lakes (Largemouth Bass and Bluegill emphasis) .......................................................................................................... 4 Sprague Lake (Trout, Bluegill, and Channel Catfish emphasis) ........................................................................................................................ 4 Chelan -

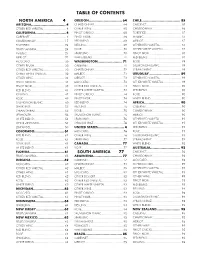

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS NORTH AMERICA 4 OREGON..........................................................................................64 CHILE..........................................................................................85 ARIZONA..........................................................................................4 CHARDONNAY..........................................................................................64 CABERNET..........................................................................................85 OTHER RED VARIETAL..........................................................................................4 OTHER WINE..........................................................................................65 CHARDONNAY..........................................................................................86 CALIFORNIA..........................................................................................4 PINOT GRIGIO..........................................................................................65 FORTIFIED..........................................................................................87 CABERNET..........................................................................................4 PINOT NOIR..........................................................................................66 MALBEC..........................................................................................87 CHARDONNAY..........................................................................................17