Download The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020 Journal

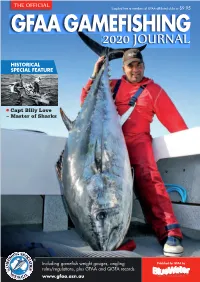

THE OFFICIAL Supplied free to members of GFAA-affiliated clubs or $9.95 GFAA GAMEFISHING 2020 JOURNAL HISTORICAL THE OFFICIAL GAME FISHING ASSOCIATION OF AUSTRALIA 2020 JOURNAL THE OFFICIAL GAME FISHING ASSOCIATION SPECIAL FEATURE •Capt Billy Love – Master of Sharks Including gamefish weight gauges, angling Published for GFAA by rules/regulations, plus GFAA and QGFA records www.gfaa.asn.au LEGENDARY POWER COUPLE THE LEGEND CONTINUES, THE NEW TEREZ SERIES OF RODS BUILT ON SPIRAL-X AND HI-POWER X BLANKS ARE THE ULTIMATE SALTWATER ENFORCER. TECHNOLOGY 8000HG MODELS INFINITE POWER CAST 6’6” HEAVY 50-150lb SPIN JIG 5’10” MEDIUM 24kg CAST 6’6” X-HEAVY 65-200lb SPIN JIG 5’8” HEAVY 37kg THE STELLA SW REPRESENTS THE PINNACLE OF CAST 6’6” XX-HEAVY 80-200lb SPIN JIG 5’9” MEDIUM / HEAVY 24-37kg SHIMANO TECHNOLOGY AND INNOVATION IN THE CAST 7’0” MEDIUM 30-65lb OVERHEAD JIG 5’10” MEDIUM 24kg PURSUIT OF CREATING THE ULTIMATE SPINNING REEL. CAST 7’0” MEDIUM / HEAVY 40-80lb OVERHEAD JIG 5’8” HEAVY 37kg SPIN 6’9” MEDIUM 20-50lb SPIN 7’6” MEDIUM 10-15kg SPIN 6’9” MEDIUM / HEAVY 40-80lb SPIN 7’6” HEAVY 15-24kg TECHNOLOGY SPIN 6’9” HEAVY 50-100lb SPIN 7’0” MEDIUM 5-10kg SPIN 6’9” X-HEAVY 65-200lb SPIN 7’0” MEDIUM / LIGHT 8-12kg UPGRADED DRAG WITH SPIN 7’2” MEDIUM / LIGHT 15-40lb SPIN 7’9” STICKBAIT PE 3-8 HEAT RESISTANCE SPIN 7’2” MEDIUM lb20-50lb SPIN 8’0” GT PE 3-8 *10000 | 14000 models only SPIN 7’2” MEDIUM / HEAVY 40-80lb Check your local Shimano Stockists today. -

Searching for Responsible and Sustainable Recreational Fisheries in the Anthropocene

Received: 10 October 2018 Accepted: 18 February 2019 DOI: 10.1111/jfb.13935 FISH SYMPOSIUM SPECIAL ISSUE REVIEW PAPER Searching for responsible and sustainable recreational fisheries in the Anthropocene Steven J. Cooke1 | William M. Twardek1 | Andrea J. Reid1 | Robert J. Lennox1 | Sascha C. Danylchuk2 | Jacob W. Brownscombe1 | Shannon D. Bower3 | Robert Arlinghaus4 | Kieran Hyder5,6 | Andy J. Danylchuk2,7 1Fish Ecology and Conservation Physiology Laboratory, Department of Biology and Recreational fisheries that use rod and reel (i.e., angling) operate around the globe in diverse Institute of Environmental and Interdisciplinary freshwater and marine habitats, targeting many different gamefish species and engaging at least Sciences, Carleton University, Ottawa, 220 million participants. The motivations for fishing vary extensively; whether anglers engage in Ontario, Canada catch-and-release or are harvest-oriented, there is strong potential for recreational fisheries to 2Fish Mission, Amherst, Massechussetts, USA be conducted in a manner that is both responsible and sustainable. There are many examples of 3Natural Resources and Sustainable Development, Uppsala University, Visby, recreational fisheries that are well-managed where anglers, the angling industry and managers Gotland, Sweden engage in responsible behaviours that both contribute to long-term sustainability of fish popula- 4Department of Biology and Ecology of Fishes, tions and the sector. Yet, recreational fisheries do not operate in a vacuum; fish populations face Leibniz-Institute -

Trout Fishing

ALBERT R. MANN LIBRARY New York State Colleges OF Agriculture and Home Economics AT Cornell University THE GIFT OF WILLARD A. KIGGINS, JR. in memory of his father Trout fishing. 3 1924 003 426 248 Cornell University Library The original of tliis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924003426248 TROUT FISHING BY THE SAME AUTHOR HOW TO FISH CONTAINING 8 TULL-PAGE ILLUSTRATIONS AND iS SMALLER ENGRAVINGS IN THE TEXT. LARGE CROWN 8vO. CLOTH. SALMON FISHING WITH A FACSIMILE IN COLOURS OF A MODEL SET OF FLIES FOR SCOTLAND, IRELAND, ENGLAND AND WALES, AND lO ILLUSTRA- TIONS FROM PHOTOGRAPHS. LARGE CROWN 8V0. CLOTH, AN ANGLER'S SEASON CONTAINING 12 PAGES OF ILLUSTRATIONS FROM PHOTOGRAPHS. LARGE CROWN 8vO. CLOTH, A. And C. BLACK, LTD., SOHO SqUARE, LONDON, W.I, AGENTS America . The Macmillan Company 64 & 66 Fifth Avenue, New York Australasia , . The Oxford University Press 205 Flinders Lane, Melbourne Canada . , The Macmillan Company of Canada, Ltd. St. Martin's House, 70 Bond Street, Toronto India , , . , Macmillan & Company, Ltd. Macmillan Building, Bombay 309 Bow Bazaar Street, Calcutta TROUT AND A SALMON. From the Picture by H, L. Rolfe. TKOUT FISHING BY W. EARL HODGSON WITH A FRONTISPIECE BY H. L. ROLFE AND A FACSIMILE IN COLOURS OF A MODEL BOOK OF FLIES, FOR STREAM AND LAKE, ARRANGED ACCORDING TO THE MONTHS IN WHICH THE LURES ARE APPROPRIATE THIRD EDITION A. & C. BLACK, LTD. 4, 5 & 6 SOHO SQUARE, LONDON, W.l. -

Find Ebook « a Book on Angling: Being a Complete Treatise on The

PPQ30KFI501J / PDF # A Book on Angling: Being a Complete Treatise on the Art of... A Book on A ngling: Being a Complete Treatise on th e A rt of A ngling in Every Branch (Classic Reprint) Filesize: 5.33 MB Reviews A whole new eBook with a new point of view. It can be rally fascinating throgh studying period of time. I am delighted to explain how this is actually the finest book i have read through during my very own life and could be he best publication for at any time. (Scarlett Stracke) DISCLAIMER | DMCA LKJ1YXOPVFGV « PDF A Book on Angling: Being a Complete Treatise on the Art of... A BOOK ON ANGLING: BEING A COMPLETE TREATISE ON THE ART OF ANGLING IN EVERY BRANCH (CLASSIC REPRINT) Forgotten Books, United States, 2015. Paperback. Book Condition: New. 229 x 152 mm. Language: English . Brand New Book ***** Print on Demand *****. A Book on Angling by Francis is a seminal piece of work on the art of fishing, the equipment used and the many techniques involved in dierent circumstances and settings. Francis puts forth an encyclopaedic breadth of information for the reader to digest, ranging from the most basic techniques to the minutest and most advanced knowledge on the subject. A Book on Angling is spread across multiple chapters, starting with an inspiring Editor s Introduction by Herbert Maxwell, wherein he bridges the gaps between time when Francis wrote this book to new developments in the field. The first half of the work is devoted to bottom fishing in which Francis explains the various styles of angling including pond fishing, punt fishing, bank fishing and various others. -

A Handbook of Angling : Teaching Fly-Fishing, Trolling

BOWNESS & BOWNESS, Fift&mg &o& STadtle MAKERS, 230, STRAND, LONDON. From BELL YARD. THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESENTED BY PROF. CHARLES A. KOFOID AND MRS. PRUDENCE W. KOFOID HANDBOOK OF ANGLING. LONDON PRINTED BY SPOTTISWOODB AND CO. NEW-STBEET SQUARE THE GOLDFINCH. BRITANNIA. ERIN GO BRAGH. J . A HANDBOOK ANGLING:OF TEACHING FLY-FISHING, TKOLLING, BOTTOM-FISHING, AND SALMON-FISHING. WITH THE NATURAL HISTOEY OF RIVER FISH, AND THE BEST MODES OF CATCHING THEM. EPHEMERA Of Bell's Life in London, AUTHOR OF 'THE BOOK OF THE SALMON 5 ETC. * I have been a great follower of fishing myself, and in its cheerful solitude have passed some of the happiest hours of a sufficiently happy life.' PALEY. FOURTH EDITION LONDON: LONGMANS, GKEEN, AND CO. 1865. PKEFACE THE THIRD EDITION. To the previous editions of this practical work I prefixed somewhat lengthened prefaces. They were then necessary, as a bush is to a new tavern not as yet renowned for its good wine. The words * Third Edition' in the present title-page are more significant than any preface. They prove that I am still called for in the fishing market. I obey the call, am thankful for the favour I have found, and shall say very little more. Five years have elapsed since I read this angling treatise through and through. Recently I have done so twice in preparing this third edition. The book appeared to me as if it had been written by another like a long-absent child whose features I had almost forgotten. I could judge of it then with less partiality than when it was fresh from my brain, and bore the defect-covering K3FM VI PREFACE TO THE THIRD EDITION. -

To Download the October 2021 Angling

ANGLING AUCTIONS SALE OF F I SHI N G T AC K L E a n d RE L AT E D I T E M S o n SAT U RD AY , 2 nd October 2 02 1 a t 12 noon 1 TERMS AND CONDITIONS 7. Catalogue Description (a) ll Lots are offered for sale as shon and nether A. BUYERS the Auctioneer nor Vendor accept any ANGLING AUCTIONS responsibility for imperfections, faults or errors 1. The Auctioneers as agent of description, buyers should satisfy themselves Unless otherwise stated,the Auctioneers act only as to the condition of any Lots prior to bidding. as agent for the Vendor. (b) Descriptions contained in the catalogue are the ANGLING AUCTIONS opinion of the Auctioneers and should not be 2. Buyer taken as a representation of statement or fact. (a) The Buyer shall be the highest bidder Some descriptions in the catalogue make SALE OF acceptable to the Auctioneer and reference to damage and/or restoration. Such theAuctioneers shall have information is given for guidance only and the absolute discretion to settle any dispute. absence of such a reference does not imply that (b) The Auctioneer reserves the right to refuse to a Lot is free from defects nor does any reference accept bids from any person or to refuse to particular defects imply the absence of others. FISHING TACKLE admission to the premises of sale without giving any reason thereof. 8. Value Added Tax And In the case of a lot marked with an asterix (*) in the 3. Buyers Premium catalogue. -

Fishing Tackle Related Items

ANGLING AUCTIONS SALE OF FISHING TACKLE and RELATED ITEMS at the CROSFIELD HALL BROADWATER ROAD ROMSEY, HANTS SO51 8GL on Saturday, 29th September 2018 at 12 noon TERMS AND CONDITIONS 7. Catalogue Description (a) All Lots are offered for sale as shown and neither A. BUYERS the Auctioneer nor Vendor accept any responsibility for imperfections, faults or errors 1. The Auctioneers as agent of description, buyers should satisfy themselves Unless otherwise stated,the Auctioneers act only as to the condition of any Lots prior to bidding. as agent for the Vendor. (b) Descriptions contained in the catalogue are the opinion of the Auctioneers and should not be 2. Buyer taken as a representation of statement or fact. (a) The Buyer shall be the highest bidder Some descriptions in the catalogue make acceptable to the Auctioneer and reference to damage and/or restoration. Such theAuctioneers shall have information is given for guidance only and the absolute discretion to settle any dispute. absence of such a reference does not imply that (b) The Auctioneer reserves the right to refuse to a Lot is free from defects nor does any reference accept bids from any person or to refuse to particular defects imply the absence of others. admission to the premises of sale without giving any reason thereof. 8. Value Added Tax In the case of a lot marked with an asterix (*) in the 3. Buyers Premium catalogue. VAT is payable on the Hammer Price. The Buyer shall pay the Auctioneer a premium of VAT is payable at the rates prevailing on the date of 18% of the Hammer Price (together with VAT at the auction. -

Atlantic Salmon Fly Tying from Past to Present

10 Isabelle Levesque Atlantic Salmon Fly Tying from past to present Without pretending to be an historian, I can state that the evolution of salmon flies has been known for over two hundred years. Over that time, and long before, many changes have come to the art of fly tying; the materials, tools, and techniques we use today are not what our predecessors used. In order to understand the modern art, a fly tier ought to know a bit of the evolution and history of line fishing, fly fishing, and the art of tying a fly. Without going into too much detail, here is a brief overview of the evolution and the art of angling and fly tying. I will start by separating the evolution of fly tying into three categories: fly fishing, the Victorian era, and the contemporary era. Historians claim that the first scriptures on flies were from Dame Juliana Berners’s Book of Saint Albans (1486), which incorporated an earlier work, A Treatise of Fishing with an Angle. The Benedictine nun wrote on outdoor recreation, the origin of artificial flies, and fly-fishing equipment. This book was updated in 1496 with additional fishing techniques. In the early 1500s, a Spanish author by the name of Fernando Basurto promoted fishing among sportsmen with hisLittle Treatise on Fishing; but the first masterpiece of English literature on fishing wasThe Compleat Angler by Izaak Walton and Charles Cotton, published in 1653. Walton was a passionate fisherman who wanted to promote fishing as an activity in communion with nature. Unlike modern books about fishing, Walton’s did not specify equipment or techniques to use in particular fishing situations. -

The Angling Library of a Gentleman

Sale 216 - January 18, 2001 The Angling Library of a Gentleman 1. Aflalo, F.G. British Salt-Water Fishes. With a Chapter on the Artificial Culture of Sea Fish by R.B. Marson. xii, 328 + [4] ad pp. Illus. with 12 chromo-lithographed plates. 10x7-1/2, original green cloth lettered in gilt on front cover & spine, gilt vignettes. London: Hutchinson, 1904. Rubbing to joints and extremities; light offset/darkening to title-page, else in very good or better condition, pages unopened. (120/180). 2. Akerman, John Yonge. Spring-Tide; or, the Angler and His Friends. [2], xv, [1], 192 pp. With steel-engraved frontispiece & 6 wood-engraved plates. 6-3/4x4-1/4, original cloth, gilt vignette of 3 fish on front cover, spine lettered in gilt. Second Edition. London: Richard Bentley, 1852. Westwood & Satchell p.3 - A writer in the Gentleman's Magazine, referring to this book, says "Never in our recollection, has the contemplative man's recreation been rendered more attractive, nor the delight of a country life set forth with a truer or more discriminating zest than in these pleasant pages." Circular stains and a few others to both covers, some wear at ends, corner bumps, leaning a bit; else very good. (250/350). WITH ACTUAL SAMPLES OF FLY-MAKING MATERIAL 3. Aldam, W.H. A Quaint Treatise on "Flees, and the Art a Artyfichall Flee Making," by an Old Man Well Known on the Derbyshire Streams as a First-Class Fly-Fisher a Century Ago. Printed from an Old Ms. Never Before Published, the Original Spelling and Language Being Retained, with Editorial Notes and Patterns of Flies, and Samples of the Materials for Making Each Fly. -

Worse Things Happen at Sea: the Welfare of Wild-Caught Fish

[ “One of the sayings of the Holy Prophet Muhammad(s) tells us: ‘If you must kill, kill without torture’” (Animals in Islam, 2010) Worse things happen at sea: the welfare of wild-caught fish Alison Mood fishcount.org.uk 2010 Acknowledgments Many thanks to Phil Brooke and Heather Pickett for reviewing this document. Phil also helped to devise the strategy presented in this report and wrote the final chapter. Cover photo credit: OAR/National Undersea Research Program (NURP). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration/Dept of Commerce. 1 Contents Executive summary 4 Section 1: Introduction to fish welfare in commercial fishing 10 10 1 Introduction 2 Scope of this report 12 3 Fish are sentient beings 14 4 Summary of key welfare issues in commercial fishing 24 Section 2: Major fishing methods and their impact on animal welfare 25 25 5 Introduction to animal welfare aspects of fish capture 6 Trawling 26 7 Purse seining 32 8 Gill nets, tangle nets and trammel nets 40 9 Rod & line and hand line fishing 44 10 Trolling 47 11 Pole & line fishing 49 12 Long line fishing 52 13 Trapping 55 14 Harpooning 57 15 Use of live bait fish in fish capture 58 16 Summary of improving welfare during capture & landing 60 Section 3: Welfare of fish after capture 66 66 17 Processing of fish alive on landing 18 Introducing humane slaughter for wild-catch fish 68 Section 4: Reducing welfare impact by reducing numbers 70 70 19 How many fish are caught each year? 20 Reducing suffering by reducing numbers caught 73 Section 5: Towards more humane fishing 81 81 21 Better welfare improves fish quality 22 Key roles for improving welfare of wild-caught fish 84 23 Strategies for improving welfare of wild-caught fish 105 Glossary 108 Worse things happen at sea: the welfare of wild-caught fish 2 References 114 Appendix A 125 fishcount.org.uk 3 Executive summary Executive Summary 1 Introduction Perhaps the most inhumane practice of all is the use of small bait fish that are impaled alive on There is increasing scientific acceptance that fish hooks, as bait for fish such as tuna. -

Sports & Pastimes

Sale 499 Thursday, February 7, 2013 11:00 AM Angling – Sports & Pastimes – Natural History Auction Preview Tuesday, February 5, 9:00 am to 5:00 pm Wednesday, February 6, 9:00 am to 5:00 pm Thursday, February 7, 9:00 am to 11:00 am Other showings by appointment 133 Kearny Street 4th Floor:San Francisco, CA 94108 phone: 415.989.2665 toll free: 1.866.999.7224 fax: 415.989.1664 [email protected]:www.pbagalleries.com REAL-TIME BIDDING AVAILABLE PBA Galleries features Real-Time Bidding for its live auctions. This feature allows Internet Users to bid on items instantaneously, as though they were in the room with the auctioneer. If it is an auction day, you may view the Real-Time Bidder at http://www.pbagalleries.com/realtimebidder/ . Instructions for its use can be found by following the link at the top of the Real-Time Bidder page. Please note: you will need to be logged in and have a credit card registered with PBA Galleries to access the Real-Time Bidder area. In addition, we continue to provide provisions for Absentee Bidding by email, fax, regular mail, and telephone prior to the auction, as well as live phone bidding during the auction. Please contact PBA Galleries for more information. IMAGES AT WWW.PBAGALLERIES.COM All the items in this catalogue are pictured in the online version of the catalogue at www.pbagalleries. com. Go to Live Auctions, click Browse Catalogues, then click on the link to the Sale. CONSIGN TO PBA GALLERIES PBA is always happy to discuss consignments of books, maps, photographs, graphics, autographs and related material. -

Fishing & Other Field Sports

Fishing & other Field Sports Fishing 2 Other Field Sports 58 Henry Sotheran Ltd 2 Sackville Street Piccadilly London W1S 3DP tel: 020 7439 6151 email: [email protected] web: sotherans.co.uk 1. ‘Arthur Holmes’ Box of Delights’ [Twelve hand- painted wooden dioramas depicting hunting, shooting and fishing scenes]. 1920. £7,500 A collection, complete in all its parts, of 12 individual hand-crafted, and numbered, three-dimensional landscaped scenes, or dioramas (all bases 163 x 95 x 10mm; the tallest insert 220mm), which are hand- painted throughout on all visible surfaces (including the oval bases, and sides) and composed of multi- layered scenery and characters which slot into the base together with exquisite detachable fishing rods with twine, floats and bait, landing birds, and even an angler’s satchel with leather strap; the whole fashioned in wood and featuring a series of figures (adults and children) engaged in traditional rural pursuits of hunting, shooting and fishing; each signed on the base, in ink, by the maker Arthur Holmes, numbered, and dated 1920 throughout; all contained within a carefully constructed custom-made wooden slatted and lidded box with metal clasp (no longer functioning) and including internal compartments and trays with leather lifting tabs configured with outlines to indicate the storage plan. This lovingly, and painstakingly, hand-crafted personal artefact is testament to the great skill and patience of the creator and is a beautiful production that would not look out of place in a museum. Unfortunately we have no provenance to offer beyond the maker’s (Arthur Holmes) signature throughout, as it originated from a provincial fair, with no associated history.