2012-Vol38-No3web.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dewey Gillespie's Hands Finish His Featherwing

“Where The Rivers Meet” The Fly Tyers of New Brunswi By Dewey Gillespie The 2nd Time Around Dewey Gillespie’s hands finish his featherwing version of NB Fly Tyer, Everett Price’s “Rose of New England Streamer” 1 Index A Albee Special 25 B Beulah Eleanor Armstrong 9 C Corinne (Legace) Gallant 12 D David Arthur LaPointe 16 E Emerson O’Dell Underhill 34 F Frank Lawrence Rickard 20 G Green Highlander 15 Green Machine 37 H Hipporous 4 I Introduction 4 J James Norton DeWitt 26 M Marie J. R. (LeBlanc) St. Laurent 31 N Nepisiguit Gray 19 O Orange Blossom Special 30 Origin of the “Deer Hair” Shady Lady 35 Origin of the Green Machine 34 2 R Ralph Turner “Ralphie” Miller 39 Red Devon 5 Rusty Wulff 41 S Sacred Cow (Holy Cow) 25 3 Introduction When the first book on New Brunswick Fly Tyers was released in 1995, I knew there were other respectable tyers that should have been including in the book. In absence of the information about those tyers I decided to proceed with what I had and over the next few years, if I could get the information on the others, I would consider releasing a second book. Never did I realize that it would take me six years to gather that information. During the six years I had the pleasure of personally meeting a number of the tyers. Sadly some of them are no longer with us. During the many meetings I had with the fly tyers, their families and friends I will never forget their kindness and generosity. -

Introduction to Fly Fishing

p Introduction to Fly Fishing Instructor: Mark Shelton, Ph.D. msheltonwkalpoly. edu (805) 756-2161 Goals for class: °Everyone learns fly fishing basics oSimplify the science, technology of fly fishing oHave fun! Course Content: Wednesday - 6:00-9:00 p.m. oSources of infonnation -Books, magazines, web sources, T.V. shows, fly fishing clubs oFly rods, reels, lines, leaders, waders, boots, nets, vests, gloves, float tubes, etc. oBasic fly fishing knots - how and when to use oGame fish identification, behavior - trout, bass, stripers, steelhead, etc. Friday- 6:00-9:00 p.m. °Aquatic entomology - what the fish eat in streams, lakes and ponds oFlies to imitate natural fish food -Dry flies, nymphs, streamers, midges, poppers, terrestrials, scuds, egg patterns oFly fishing strategies Reading the water Stealthy presentations Fishing dries, nymphs, etc. Strike indicators, dropper fly rigs, line mending oSlides/video offly fishing tactics Saturday - 8:30-4:30 p.m. oFly casting video oFly casting - on lawn oTrip to local farm pond for casting on water oTrip to local stream to read water, practice nymphing bz ·0-----------------.. -. FLY FISIDNG INFORMATION SOURCES Books: A Treatyse ofFysshynge with an Angle. 1496. Dame Juliana Bemers? -1 st book on fly fishing The Curtis Creek Manifesto. 1978. Anderson. Fly Fishing Strategy. 1988. Swisher and Richards. A River Runs Through It. 1989. Maclean. Joan Wulff's Fly Fishing: Expert Advicefrom a Woman's Perspective. 1991. Wulff. California Blue-Ribbon Trout Streams. 1991. Sunderland and Lackey. Joe Humphrey's Trout Tactics. 1993. Humphreys. Western Fly-Fishing Strategies. 1998. Mathews. 2 - p---------- Books con't. Stripers on the Fly. -

Fly-Fishing Boy Scouts of America Merit Badge Series

FLY-FISHING BOY SCOUTS OF AMERICA MERIT BADGE SERIES FLY-FISHING “Enhancing our youths’ competitive edge through merit badges” Requirements 1. Do the following: a. Explain to your counselor the most likely hazards you may encounter while participating in fly-fishing activities and what you should do to anticipate, help prevent, mitigate, and respond to these hazards. Name and explain five safety practices you should always follow while fly-fishing. b. Discuss the prevention of and treatment for health concerns that could occur while fly-fishing, including cuts and scratches, puncture wounds, insect bites, hypothermia, dehydration, heat exhaustion, heatstroke, and sunburn. c. Explain how to remove a hook that has lodged in your arm. 2. Demonstrate how to match a fly rod, line, and leader to achieve a balanced system. Discuss several types of fly lines, and explain how and when each would be used. Review with your counselor how to care for this equipment. 3. Demonstrate how to tie proper knots to prepare a fly rod for fishing: a. Tie backing to the arbor of a fly reel spool using an arbor knot. b. Tie backing to the fly line using a nail knot. c. Attach a leader to the fly line using a nail knot or a loop-to-loop connection. d. Add a tippet to a leader using a surgeon’s knot or a loop-to-loop connection. e. Tie a fly onto the terminal end of the leader using an improved clinch knot. 35900 ISBN 978-0-8395-3283-5 ©2021 Boy Scouts of America 2021 Printing 4. -

SPORT FISH of OHIO Identification DIVISION of WILDLIFE

SPORT FISH OF OHIO identification DIVISION OF WILDLIFE 1 With more than 40,000 miles of streams, 2.4 million acres of Lake Erie and inland water, and 450 miles of the Ohio River, Ohio supports a diverse and abundant fish fauna represented by more than 160 species. Ohio’s fishes come in a wide range of sizes, shapes and colors...and live in a variety of aquatic habitats from our largest lakes and rivers to the smallest ponds and creeks. Approximately one-third of these species can be found in this guide. This fish identification guide provides color illustrations to help anglers identify their catch, and useful tips to help catch more fish. We hope it will also increase your awareness of the diversity of fishes in Ohio. This book also gives information about the life history of 27 of Ohio’s commonly caught species, as well as information on selected threatened and endangered species. Color illustrations and names are also offered for 20 additional species, many of which are rarely caught by anglers, but are quite common throughout Ohio. Fishing is a favorite pastime of many Ohioans and one of the most enduring family traditions. A first fish or day shared on the water are memories that last a lifetime. It is our sincere hope that the information in this guide will contribute significantly to your fishing experiences and understanding of Ohio’s fishes. Good Fishing! The ODNR Division of Wildlife manages the fisheries of more than 160,000 acres of inland water, 7,000 miles of streams, and 2.25 million acres of Lake Erie. -

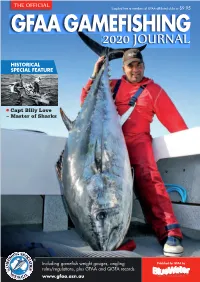

2020 Journal

THE OFFICIAL Supplied free to members of GFAA-affiliated clubs or $9.95 GFAA GAMEFISHING 2020 JOURNAL HISTORICAL THE OFFICIAL GAME FISHING ASSOCIATION OF AUSTRALIA 2020 JOURNAL THE OFFICIAL GAME FISHING ASSOCIATION SPECIAL FEATURE •Capt Billy Love – Master of Sharks Including gamefish weight gauges, angling Published for GFAA by rules/regulations, plus GFAA and QGFA records www.gfaa.asn.au LEGENDARY POWER COUPLE THE LEGEND CONTINUES, THE NEW TEREZ SERIES OF RODS BUILT ON SPIRAL-X AND HI-POWER X BLANKS ARE THE ULTIMATE SALTWATER ENFORCER. TECHNOLOGY 8000HG MODELS INFINITE POWER CAST 6’6” HEAVY 50-150lb SPIN JIG 5’10” MEDIUM 24kg CAST 6’6” X-HEAVY 65-200lb SPIN JIG 5’8” HEAVY 37kg THE STELLA SW REPRESENTS THE PINNACLE OF CAST 6’6” XX-HEAVY 80-200lb SPIN JIG 5’9” MEDIUM / HEAVY 24-37kg SHIMANO TECHNOLOGY AND INNOVATION IN THE CAST 7’0” MEDIUM 30-65lb OVERHEAD JIG 5’10” MEDIUM 24kg PURSUIT OF CREATING THE ULTIMATE SPINNING REEL. CAST 7’0” MEDIUM / HEAVY 40-80lb OVERHEAD JIG 5’8” HEAVY 37kg SPIN 6’9” MEDIUM 20-50lb SPIN 7’6” MEDIUM 10-15kg SPIN 6’9” MEDIUM / HEAVY 40-80lb SPIN 7’6” HEAVY 15-24kg TECHNOLOGY SPIN 6’9” HEAVY 50-100lb SPIN 7’0” MEDIUM 5-10kg SPIN 6’9” X-HEAVY 65-200lb SPIN 7’0” MEDIUM / LIGHT 8-12kg UPGRADED DRAG WITH SPIN 7’2” MEDIUM / LIGHT 15-40lb SPIN 7’9” STICKBAIT PE 3-8 HEAT RESISTANCE SPIN 7’2” MEDIUM lb20-50lb SPIN 8’0” GT PE 3-8 *10000 | 14000 models only SPIN 7’2” MEDIUM / HEAVY 40-80lb Check your local Shimano Stockists today. -

Arizona Fishing Regulations 3 Fishing License Fees Getting Started

2019 & 2020 Fishing Regulations for your boat for your boat See how much you could savegeico.com on boat | 1-800-865-4846insurance. | Local Offi ce geico.com | 1-800-865-4846 | Local Offi ce See how much you could save on boat insurance. Some discounts, coverages, payment plans and features are not available in all states or all GEICO companies. Boat and PWC coverages are underwritten by GEICO Marine Insurance Company. GEICO is a registered service mark of Government Employees Insurance Company, Washington, D.C. 20076; a Berkshire Hathaway Inc. subsidiary. TowBoatU.S. is the preferred towing service provider for GEICO Marine Insurance. The GEICO Gecko Image © 1999-2017. © 2017 GEICO AdPages2019.indd 2 12/4/2018 1:14:48 PM AdPages2019.indd 3 12/4/2018 1:17:19 PM Table of Contents Getting Started License Information and Fees ..........................................3 Douglas A. Ducey Governor Regulation Changes ...........................................................4 ARIZONA GAME AND FISH COMMISSION How to Use This Booklet ...................................................5 JAMES S. ZIELER, CHAIR — St. Johns ERIC S. SPARKS — Tucson General Statewide Fishing Regulations KURT R. DAVIS — Phoenix LELAND S. “BILL” BRAKE — Elgin Bag and Possession Limits ................................................6 JAMES R. AMMONS — Yuma Statewide Fishing Regulations ..........................................7 ARIZONA GAME AND FISH DEPARTMENT Common Violations ...........................................................8 5000 W. Carefree Highway Live Baitfish -

Searching for Responsible and Sustainable Recreational Fisheries in the Anthropocene

Received: 10 October 2018 Accepted: 18 February 2019 DOI: 10.1111/jfb.13935 FISH SYMPOSIUM SPECIAL ISSUE REVIEW PAPER Searching for responsible and sustainable recreational fisheries in the Anthropocene Steven J. Cooke1 | William M. Twardek1 | Andrea J. Reid1 | Robert J. Lennox1 | Sascha C. Danylchuk2 | Jacob W. Brownscombe1 | Shannon D. Bower3 | Robert Arlinghaus4 | Kieran Hyder5,6 | Andy J. Danylchuk2,7 1Fish Ecology and Conservation Physiology Laboratory, Department of Biology and Recreational fisheries that use rod and reel (i.e., angling) operate around the globe in diverse Institute of Environmental and Interdisciplinary freshwater and marine habitats, targeting many different gamefish species and engaging at least Sciences, Carleton University, Ottawa, 220 million participants. The motivations for fishing vary extensively; whether anglers engage in Ontario, Canada catch-and-release or are harvest-oriented, there is strong potential for recreational fisheries to 2Fish Mission, Amherst, Massechussetts, USA be conducted in a manner that is both responsible and sustainable. There are many examples of 3Natural Resources and Sustainable Development, Uppsala University, Visby, recreational fisheries that are well-managed where anglers, the angling industry and managers Gotland, Sweden engage in responsible behaviours that both contribute to long-term sustainability of fish popula- 4Department of Biology and Ecology of Fishes, tions and the sector. Yet, recreational fisheries do not operate in a vacuum; fish populations face Leibniz-Institute -

The Eight Classic Nymphs and How to Fish Them

Orvis Early Season Weighted Nymph Selection The Eight Classic Nymphs and How to Fish Them Manchester, Vermont 05254 Makers of Fine Fishing Tackle Since 1856 This article was recreated by Bob Hazlett from a very old black and white pamphlet by Orvis found at the bottom of a box of fly-tying material. The text is original; the photos are modern color renditions of those in the original. Page 1 of 7 The Eight Classic Nymphs and How to Fish Them All trout waters, including streams, lakes and ponds contain thousands of different insects upon which trout feed. The immature forms of these insects are called nymphs. Dwelling on the bottom, they can be found year-round and are a major factor in the trout's diet. The flies in this selection were designed to imitate the nymphal forms of the insect orders most important to the trout fisherman. These include the mayflies, the stoneflies and the caddisflies. Weighted nymphs can provide an effective approach when conditions are uncertain or if trout are not feeding on the surface. At streamside, we are always alert for some clue to fly selection. But as so often happens throughout the season, we arrive on the stream and there are no flies hatching. In need of a starting point, many experienced hands begin to systematically probe the waters with weighted nymphs. Which nymph to try first? One that is suggestive in size and color of the naturals in the particular water one is fishing. Naturals can be dislodged from stream bed rocks or submerged logs and examined closely. -

Trout Fishing

ALBERT R. MANN LIBRARY New York State Colleges OF Agriculture and Home Economics AT Cornell University THE GIFT OF WILLARD A. KIGGINS, JR. in memory of his father Trout fishing. 3 1924 003 426 248 Cornell University Library The original of tliis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924003426248 TROUT FISHING BY THE SAME AUTHOR HOW TO FISH CONTAINING 8 TULL-PAGE ILLUSTRATIONS AND iS SMALLER ENGRAVINGS IN THE TEXT. LARGE CROWN 8vO. CLOTH. SALMON FISHING WITH A FACSIMILE IN COLOURS OF A MODEL SET OF FLIES FOR SCOTLAND, IRELAND, ENGLAND AND WALES, AND lO ILLUSTRA- TIONS FROM PHOTOGRAPHS. LARGE CROWN 8V0. CLOTH, AN ANGLER'S SEASON CONTAINING 12 PAGES OF ILLUSTRATIONS FROM PHOTOGRAPHS. LARGE CROWN 8vO. CLOTH, A. And C. BLACK, LTD., SOHO SqUARE, LONDON, W.I, AGENTS America . The Macmillan Company 64 & 66 Fifth Avenue, New York Australasia , . The Oxford University Press 205 Flinders Lane, Melbourne Canada . , The Macmillan Company of Canada, Ltd. St. Martin's House, 70 Bond Street, Toronto India , , . , Macmillan & Company, Ltd. Macmillan Building, Bombay 309 Bow Bazaar Street, Calcutta TROUT AND A SALMON. From the Picture by H, L. Rolfe. TKOUT FISHING BY W. EARL HODGSON WITH A FRONTISPIECE BY H. L. ROLFE AND A FACSIMILE IN COLOURS OF A MODEL BOOK OF FLIES, FOR STREAM AND LAKE, ARRANGED ACCORDING TO THE MONTHS IN WHICH THE LURES ARE APPROPRIATE THIRD EDITION A. & C. BLACK, LTD. 4, 5 & 6 SOHO SQUARE, LONDON, W.l. -

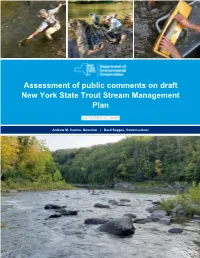

Assessment of Public Comment on Draft Trout Stream Management Plan

Assessment of public comments on draft New York State Trout Stream Management Plan OCTOBER 27, 2020 Andrew M. Cuomo, Governor | Basil Seggos, Commissioner A draft of the Fisheries Management Plan for Inland Trout Streams in New York State (Plan) was released for public review on May 26, 2020 with the comment period extending through June 25, 2020. Public comment was solicited through a variety of avenues including: • a posting of the statewide public comment period in the Environmental Notice Bulletin (ENB), • a DEC news release distributed statewide, • an announcement distributed to all e-mail addresses provided by participants at the 2017 and 2019 public meetings on trout stream management described on page 11 of the Plan [353 recipients, 181 unique opens (58%)], and • an announcement distributed to all subscribers to the DEC Delivers Freshwater Fishing and Boating Group [138,122 recipients, 34,944 unique opens (26%)]. A total of 489 public comments were received through e-mail or letters (Appendix A, numbered 1-277 and 300-511). 471 of these comments conveyed specific concerns, recommendations or endorsements; the other 18 comments were general statements or pertained to issues outside the scope of the plan. General themes to recurring comments were identified (22 total themes), and responses to these are included below. These themes only embrace recommendations or comments of concern. Comments that represent favorable and supportive views are not included in this assessment. Duplicate comment source numbers associated with a numbered theme reflect comments on subtopics within the general theme. Theme #1 The statewide catch and release (artificial lures only) season proposed to run from October 16 through March 31 poses a risk to the sustainability of wild trout populations and the quality of the fisheries they support that is either wholly unacceptable or of great concern, particularly in some areas of the state; notably Delaware/Catskill waters. -

Merritt Island National Wildlife Refuge

Merritt Island National Wildlife Refuge Comprehensive Conservation Plan U.S. Department of the Interior Fish and Wildlife Service Southeast Region August 2008 COMPREHENSIVE CONSERVATION PLAN MERRITT ISLAND NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGE Brevard and Volusia Counties, Florida U.S. Department of the Interior Fish and Wildlife Service Southeast Region Atlanta, Georgia August 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS COMPREHENSIVE CONSERVATION PLAN EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................................................... 1 I. BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................................. 3 Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 3 Purpose and Need for the Plan .................................................................................................... 3 U.S. Fish And Wildlife Service ...................................................................................................... 4 National Wildlife Refuge System .................................................................................................. 4 Legal Policy Context ..................................................................................................................... 5 National Conservation Plans and Initiatives .................................................................................6 Relationship to State Partners ..................................................................................................... -

Jackson Region Fisheries Newsletter

WYOMING GAME AND FISH May 2011 DEPARTMENT Volume 8 Jackson Region Fisheries Newsletter Exploring the Greyback Once again the Jackson Regional Angler Newsletter is fea- turing a geographical region within the headwaters of the Snake River drainage. This year, the Greys River and Hoback River (commonly known as the Greyback) is receiving the attention. In the past, the areas we have explored have been wilderness areas, the Greyback is not within wilderness and therefore, offers a variety of different recreational opportunities for anglers and adventurists. From ATV’s to mountain bikes and horses to snowmachines, this area allows for a diversity of activities for everyone’s interests. Get out there and explore the Greyback! West Dell Drainage Inside This Issue: When the Skiing Gets Tough, ● The Tough go Fishing ● Flat Creek the Tough Go Fishing ● Essential Flies Winter fly fishing isn’t for everyone. When your rod ices up and you have to ● Take Me Fishing wear gloves to keep your hands from doing the same, it takes a special person to ● say, “let’s try the next hole”. Late winter and early spring however, have produced Exploring Greyback (Newsletter insert) some of the best dry fly fishing I have seen on the Snake River. Why? Because, from February through April, Winter Stoneflies (Family: Capniidae) begin to hatch in large numbers. These small invertebrates spend most of their life cycle embedded in the substrate at the bottom of the river. Locally, the dry hatch peaks on the first calm days of the year when the air temperature exceeds 40 de- grees.