A Handbook of Angling : Teaching Fly-Fishing, Trolling

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dewey Gillespie's Hands Finish His Featherwing

“Where The Rivers Meet” The Fly Tyers of New Brunswi By Dewey Gillespie The 2nd Time Around Dewey Gillespie’s hands finish his featherwing version of NB Fly Tyer, Everett Price’s “Rose of New England Streamer” 1 Index A Albee Special 25 B Beulah Eleanor Armstrong 9 C Corinne (Legace) Gallant 12 D David Arthur LaPointe 16 E Emerson O’Dell Underhill 34 F Frank Lawrence Rickard 20 G Green Highlander 15 Green Machine 37 H Hipporous 4 I Introduction 4 J James Norton DeWitt 26 M Marie J. R. (LeBlanc) St. Laurent 31 N Nepisiguit Gray 19 O Orange Blossom Special 30 Origin of the “Deer Hair” Shady Lady 35 Origin of the Green Machine 34 2 R Ralph Turner “Ralphie” Miller 39 Red Devon 5 Rusty Wulff 41 S Sacred Cow (Holy Cow) 25 3 Introduction When the first book on New Brunswick Fly Tyers was released in 1995, I knew there were other respectable tyers that should have been including in the book. In absence of the information about those tyers I decided to proceed with what I had and over the next few years, if I could get the information on the others, I would consider releasing a second book. Never did I realize that it would take me six years to gather that information. During the six years I had the pleasure of personally meeting a number of the tyers. Sadly some of them are no longer with us. During the many meetings I had with the fly tyers, their families and friends I will never forget their kindness and generosity. -

Fishing Tackle Related Items

ANGLING AUCTIONS SALE OF FISHING TACKLE and RELATED ITEMS at the CROSFIELD HALL BROADWATER ROAD ROMSEY, HANTS SO51 8GL on SATURDAY, 5th October 2019 at 12 noon TERMS AND CONDITIONS 7. Catalogue Description (a) All Lots are offered for sale as shown and neither A. BUYERS the Auctioneer nor Vendor accept any responsibility for imperfections, faults or errors 1. The Auctioneers as agent of description, buyers should satisfy themselves Unless otherwise stated,the Auctioneers act only as to the condition of any Lots prior to bidding. as agent for the Vendor. (b) Descriptions contained in the catalogue are the opinion of the Auctioneers and should not be 2. Buyer taken as a representation of statement or fact. (a) The Buyer shall be the highest bidder Some descriptions in the catalogue make acceptable to the Auctioneer and reference to damage and/or restoration. Such theAuctioneers shall have information is given for guidance only and the absolute discretion to settle any dispute. absence of such a reference does not imply that (b) The Auctioneer reserves the right to refuse to a Lot is free from defects nor does any reference accept bids from any person or to refuse to particular defects imply the absence of others. admission to the premises of sale without giving any reason thereof. 8. Value Added Tax In the case of a lot marked with an asterix (*) in the 3. Buyers Premium catalogue. VAT is payable on the Hammer Price. The Buyer shall pay the Auctioneer a premium of VAT is payable at the rates prevailing on the date of 18% of the Hammer Price (together with VAT at the auction. -

Langley's Trout Candy by Kevin Cohenour

Langley’s Trout Candy by Kevin Cohenour Every once in awhile a fly pattern comes along, such as the Clouser Minnow and Lefty's Deceiver, that will catch most any species. The Trout Candy has proven itself to be in that category. I first learned of this pattern in 1996 when I walked into Jacksonville’s Salty Feather JUNEFEBRUARY 20012002 fly shop. I asked owner John Bottko for a pattern I could tie for redfish and trout. He described the FLIES & LIES VIA E-MAIL Trout Candy for me. Originated by Alan Langley of Jacksonville, the Trout Candy began as a pattern to catch sea trout. But as we quickly Computer whiz Kevin Cohenour has found, it is an extremely effective redfish fly. figured out an easy way for you to receive Tied in smaller sizes (6 & 8) it has taken “Flies & Lies” via e-mail in the format of a bonefish in the keys. With a marabou tail it has “PDF” file. Your computer will probably fooled salmon and rainbows in Alaska. It will already read a PDF file with Adobe Acrobat catch ladyfish all day long, entices snook and or similar software. If not, free downloads jacks, and has even landed flounder and are available. croakers. Tied in size 1 or 2 with large eyes it We will send the June issue via mail will get down in the surf to the cruising reds. and e-mail on a trial basis, Thereafter, if you The first redfish I ever caught was on a choose, we can send your copy by e-mail size 4 Trout Candy I had tied from John’s verbal alone. -

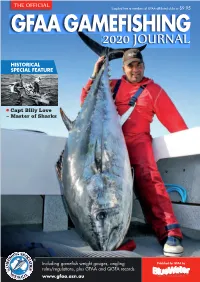

2020 Journal

THE OFFICIAL Supplied free to members of GFAA-affiliated clubs or $9.95 GFAA GAMEFISHING 2020 JOURNAL HISTORICAL THE OFFICIAL GAME FISHING ASSOCIATION OF AUSTRALIA 2020 JOURNAL THE OFFICIAL GAME FISHING ASSOCIATION SPECIAL FEATURE •Capt Billy Love – Master of Sharks Including gamefish weight gauges, angling Published for GFAA by rules/regulations, plus GFAA and QGFA records www.gfaa.asn.au LEGENDARY POWER COUPLE THE LEGEND CONTINUES, THE NEW TEREZ SERIES OF RODS BUILT ON SPIRAL-X AND HI-POWER X BLANKS ARE THE ULTIMATE SALTWATER ENFORCER. TECHNOLOGY 8000HG MODELS INFINITE POWER CAST 6’6” HEAVY 50-150lb SPIN JIG 5’10” MEDIUM 24kg CAST 6’6” X-HEAVY 65-200lb SPIN JIG 5’8” HEAVY 37kg THE STELLA SW REPRESENTS THE PINNACLE OF CAST 6’6” XX-HEAVY 80-200lb SPIN JIG 5’9” MEDIUM / HEAVY 24-37kg SHIMANO TECHNOLOGY AND INNOVATION IN THE CAST 7’0” MEDIUM 30-65lb OVERHEAD JIG 5’10” MEDIUM 24kg PURSUIT OF CREATING THE ULTIMATE SPINNING REEL. CAST 7’0” MEDIUM / HEAVY 40-80lb OVERHEAD JIG 5’8” HEAVY 37kg SPIN 6’9” MEDIUM 20-50lb SPIN 7’6” MEDIUM 10-15kg SPIN 6’9” MEDIUM / HEAVY 40-80lb SPIN 7’6” HEAVY 15-24kg TECHNOLOGY SPIN 6’9” HEAVY 50-100lb SPIN 7’0” MEDIUM 5-10kg SPIN 6’9” X-HEAVY 65-200lb SPIN 7’0” MEDIUM / LIGHT 8-12kg UPGRADED DRAG WITH SPIN 7’2” MEDIUM / LIGHT 15-40lb SPIN 7’9” STICKBAIT PE 3-8 HEAT RESISTANCE SPIN 7’2” MEDIUM lb20-50lb SPIN 8’0” GT PE 3-8 *10000 | 14000 models only SPIN 7’2” MEDIUM / HEAVY 40-80lb Check your local Shimano Stockists today. -

Searching for Responsible and Sustainable Recreational Fisheries in the Anthropocene

Received: 10 October 2018 Accepted: 18 February 2019 DOI: 10.1111/jfb.13935 FISH SYMPOSIUM SPECIAL ISSUE REVIEW PAPER Searching for responsible and sustainable recreational fisheries in the Anthropocene Steven J. Cooke1 | William M. Twardek1 | Andrea J. Reid1 | Robert J. Lennox1 | Sascha C. Danylchuk2 | Jacob W. Brownscombe1 | Shannon D. Bower3 | Robert Arlinghaus4 | Kieran Hyder5,6 | Andy J. Danylchuk2,7 1Fish Ecology and Conservation Physiology Laboratory, Department of Biology and Recreational fisheries that use rod and reel (i.e., angling) operate around the globe in diverse Institute of Environmental and Interdisciplinary freshwater and marine habitats, targeting many different gamefish species and engaging at least Sciences, Carleton University, Ottawa, 220 million participants. The motivations for fishing vary extensively; whether anglers engage in Ontario, Canada catch-and-release or are harvest-oriented, there is strong potential for recreational fisheries to 2Fish Mission, Amherst, Massechussetts, USA be conducted in a manner that is both responsible and sustainable. There are many examples of 3Natural Resources and Sustainable Development, Uppsala University, Visby, recreational fisheries that are well-managed where anglers, the angling industry and managers Gotland, Sweden engage in responsible behaviours that both contribute to long-term sustainability of fish popula- 4Department of Biology and Ecology of Fishes, tions and the sector. Yet, recreational fisheries do not operate in a vacuum; fish populations face Leibniz-Institute -

Trout Fishing

ALBERT R. MANN LIBRARY New York State Colleges OF Agriculture and Home Economics AT Cornell University THE GIFT OF WILLARD A. KIGGINS, JR. in memory of his father Trout fishing. 3 1924 003 426 248 Cornell University Library The original of tliis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924003426248 TROUT FISHING BY THE SAME AUTHOR HOW TO FISH CONTAINING 8 TULL-PAGE ILLUSTRATIONS AND iS SMALLER ENGRAVINGS IN THE TEXT. LARGE CROWN 8vO. CLOTH. SALMON FISHING WITH A FACSIMILE IN COLOURS OF A MODEL SET OF FLIES FOR SCOTLAND, IRELAND, ENGLAND AND WALES, AND lO ILLUSTRA- TIONS FROM PHOTOGRAPHS. LARGE CROWN 8V0. CLOTH, AN ANGLER'S SEASON CONTAINING 12 PAGES OF ILLUSTRATIONS FROM PHOTOGRAPHS. LARGE CROWN 8vO. CLOTH, A. And C. BLACK, LTD., SOHO SqUARE, LONDON, W.I, AGENTS America . The Macmillan Company 64 & 66 Fifth Avenue, New York Australasia , . The Oxford University Press 205 Flinders Lane, Melbourne Canada . , The Macmillan Company of Canada, Ltd. St. Martin's House, 70 Bond Street, Toronto India , , . , Macmillan & Company, Ltd. Macmillan Building, Bombay 309 Bow Bazaar Street, Calcutta TROUT AND A SALMON. From the Picture by H, L. Rolfe. TKOUT FISHING BY W. EARL HODGSON WITH A FRONTISPIECE BY H. L. ROLFE AND A FACSIMILE IN COLOURS OF A MODEL BOOK OF FLIES, FOR STREAM AND LAKE, ARRANGED ACCORDING TO THE MONTHS IN WHICH THE LURES ARE APPROPRIATE THIRD EDITION A. & C. BLACK, LTD. 4, 5 & 6 SOHO SQUARE, LONDON, W.l. -

From the Editor Club Meetings Trout U Nlim Ited N Otices Contacts

A PUBLICATION OF The Northern Lights Fly Tyers & Fishers PROVIDING A FRIENDLY ATMOSPHERE FOR THE NOVICE AND EXPERT Northern Lights TO LEARN AND SHARE THE FLY TYING AND FISHING EXPERIENCE Fly Tyers & Fishers VOLU ME 9 ISSU E 3 REVISED MARCH , 2005 From the Editor Contacts Last of the “Winter” Season in Full Swing! (Program Revision on March 3) President nd Dennis Southwick This month kicked off on the 2 with Barry White demonstrating his burlap stone, Lance (780) 463-6533 Taylor the RS Quad and Dennis Southwick the SA Hopper in honor of Roman Scharabun. [email protected] The second week, on the 9th, we will have a TU donation Fly Tye. That’s followed on the 16th by a Club swap meet. The 23rd will have President Dennis Southwick tying his “Spastic Vice-President Weevil”. We end the month on the 30th with Michael Dell talking about Vests. Brian Bleackley (780) 718-1428 The Iron Fly Tyer event was a rousing success again! We had over 50 people show up to [email protected] watch Master Michael, Sponge Bobber and Dale John Stone try to cope with bamboo as the mystery material. The crowed was amazed at the tying skills and imagination employed by Secretary the participants. Dale Johnson emerged as the victor. Way to go Dale! You can find photos of John Marple the event and the flies tied in the forum on the club web page. My thanks go to the (780) 435-5386 participants, the judges and the photographers. Job well done by all! Program The salmon fly postage stamp tyers have not yet completed their flies as there were too many Dave Murray interesting events last month. -

Find Ebook « a Book on Angling: Being a Complete Treatise on The

PPQ30KFI501J / PDF # A Book on Angling: Being a Complete Treatise on the Art of... A Book on A ngling: Being a Complete Treatise on th e A rt of A ngling in Every Branch (Classic Reprint) Filesize: 5.33 MB Reviews A whole new eBook with a new point of view. It can be rally fascinating throgh studying period of time. I am delighted to explain how this is actually the finest book i have read through during my very own life and could be he best publication for at any time. (Scarlett Stracke) DISCLAIMER | DMCA LKJ1YXOPVFGV « PDF A Book on Angling: Being a Complete Treatise on the Art of... A BOOK ON ANGLING: BEING A COMPLETE TREATISE ON THE ART OF ANGLING IN EVERY BRANCH (CLASSIC REPRINT) Forgotten Books, United States, 2015. Paperback. Book Condition: New. 229 x 152 mm. Language: English . Brand New Book ***** Print on Demand *****. A Book on Angling by Francis is a seminal piece of work on the art of fishing, the equipment used and the many techniques involved in dierent circumstances and settings. Francis puts forth an encyclopaedic breadth of information for the reader to digest, ranging from the most basic techniques to the minutest and most advanced knowledge on the subject. A Book on Angling is spread across multiple chapters, starting with an inspiring Editor s Introduction by Herbert Maxwell, wherein he bridges the gaps between time when Francis wrote this book to new developments in the field. The first half of the work is devoted to bottom fishing in which Francis explains the various styles of angling including pond fishing, punt fishing, bank fishing and various others. -

To Download the October 2021 Angling

ANGLING AUCTIONS SALE OF F I SHI N G T AC K L E a n d RE L AT E D I T E M S o n SAT U RD AY , 2 nd October 2 02 1 a t 12 noon 1 TERMS AND CONDITIONS 7. Catalogue Description (a) ll Lots are offered for sale as shon and nether A. BUYERS the Auctioneer nor Vendor accept any ANGLING AUCTIONS responsibility for imperfections, faults or errors 1. The Auctioneers as agent of description, buyers should satisfy themselves Unless otherwise stated,the Auctioneers act only as to the condition of any Lots prior to bidding. as agent for the Vendor. (b) Descriptions contained in the catalogue are the ANGLING AUCTIONS opinion of the Auctioneers and should not be 2. Buyer taken as a representation of statement or fact. (a) The Buyer shall be the highest bidder Some descriptions in the catalogue make SALE OF acceptable to the Auctioneer and reference to damage and/or restoration. Such theAuctioneers shall have information is given for guidance only and the absolute discretion to settle any dispute. absence of such a reference does not imply that (b) The Auctioneer reserves the right to refuse to a Lot is free from defects nor does any reference accept bids from any person or to refuse to particular defects imply the absence of others. FISHING TACKLE admission to the premises of sale without giving any reason thereof. 8. Value Added Tax And In the case of a lot marked with an asterix (*) in the 3. Buyers Premium catalogue. -

Fishing Tackle Related Items

ANGLING AUCTIONS SALE OF FISHING TACKLE and RELATED ITEMS at the CROSFIELD HALL BROADWATER ROAD ROMSEY, HANTS SO51 8GL on Saturday, 29th September 2018 at 12 noon TERMS AND CONDITIONS 7. Catalogue Description (a) All Lots are offered for sale as shown and neither A. BUYERS the Auctioneer nor Vendor accept any responsibility for imperfections, faults or errors 1. The Auctioneers as agent of description, buyers should satisfy themselves Unless otherwise stated,the Auctioneers act only as to the condition of any Lots prior to bidding. as agent for the Vendor. (b) Descriptions contained in the catalogue are the opinion of the Auctioneers and should not be 2. Buyer taken as a representation of statement or fact. (a) The Buyer shall be the highest bidder Some descriptions in the catalogue make acceptable to the Auctioneer and reference to damage and/or restoration. Such theAuctioneers shall have information is given for guidance only and the absolute discretion to settle any dispute. absence of such a reference does not imply that (b) The Auctioneer reserves the right to refuse to a Lot is free from defects nor does any reference accept bids from any person or to refuse to particular defects imply the absence of others. admission to the premises of sale without giving any reason thereof. 8. Value Added Tax In the case of a lot marked with an asterix (*) in the 3. Buyers Premium catalogue. VAT is payable on the Hammer Price. The Buyer shall pay the Auctioneer a premium of VAT is payable at the rates prevailing on the date of 18% of the Hammer Price (together with VAT at the auction. -

Atlantic Salmon Fly Tying from Past to Present

10 Isabelle Levesque Atlantic Salmon Fly Tying from past to present Without pretending to be an historian, I can state that the evolution of salmon flies has been known for over two hundred years. Over that time, and long before, many changes have come to the art of fly tying; the materials, tools, and techniques we use today are not what our predecessors used. In order to understand the modern art, a fly tier ought to know a bit of the evolution and history of line fishing, fly fishing, and the art of tying a fly. Without going into too much detail, here is a brief overview of the evolution and the art of angling and fly tying. I will start by separating the evolution of fly tying into three categories: fly fishing, the Victorian era, and the contemporary era. Historians claim that the first scriptures on flies were from Dame Juliana Berners’s Book of Saint Albans (1486), which incorporated an earlier work, A Treatise of Fishing with an Angle. The Benedictine nun wrote on outdoor recreation, the origin of artificial flies, and fly-fishing equipment. This book was updated in 1496 with additional fishing techniques. In the early 1500s, a Spanish author by the name of Fernando Basurto promoted fishing among sportsmen with hisLittle Treatise on Fishing; but the first masterpiece of English literature on fishing wasThe Compleat Angler by Izaak Walton and Charles Cotton, published in 1653. Walton was a passionate fisherman who wanted to promote fishing as an activity in communion with nature. Unlike modern books about fishing, Walton’s did not specify equipment or techniques to use in particular fishing situations. -

By Joseph D. Bates Jr. and Pamela Bates Richards (Mechanicsburg, Pa.: Executive Assistant Marianne Kennedy Stackpole Books, 1996)

Thaw HE FEBRUARYTHAW comes to Ver- "From the Old to the New in Salmon mont. The ice melts, the earth loosens. Flies" is our excerpt from Fishing Atlantic TI splash my way to the post office ankle Salmon: The Flies and the Patterns (reviewed deep in puddles and mud, dreaming of being by Bill Hunter in the Winter 1997 issue). waist deep in water. It is so warm I can smell When Joseph D. Bates Jr. died in 1988, he left things. The other day I glimpsed a snow flur- this work in progress. Pamela Bates Richards, ry that turned out to be an insect. (As most his daughter, added significant material to anglers can attest, one often needs to expect the text and spearheaded its publication, to see something in order to see it at all.) Se- working closely with Museum staff during ductive, a tease, the thaw stays long enough her research. The book, released late last year to infect us with the fever, then leaves, laugh- by Stackpole Books, includes more than ing as we exhibit the appropriate withdrawal 160 striking color plates by photographer symptoms. Michael D. Radencich. We are pleased to re- By the time these words are printed and produce eight of these. distributed, I hope the true thaw will be Spring fever finds its expression in fishing upon us here and that those (perhaps few) of and romance in Gordon M. Wickstrom's us who retire our gear for the winter will reminiscence of "A Memoir of Trout and Eros once again be on the water.