Historical Monuments at Rawat Near Islamabad

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PAKISTAN Haveli, the Defining Symbol of Rohtas Fort

Restoring Man Singh PAKISTAN Haveli, the defining symbol of Rohtas Fort ohtas Fort has towered majestically on its height above the ancient "royal road" since it was con- Rstructed in 1541 by Emperor Sher Shah Suri after his defeat of Mogul Emperor Humayun. It is one of the most important historical medieval forts still in existence in Pakistan. Within the four-kilometer cir- cumference of this World Heritage Site is the Man Singh Haveli, a Rajput palace. Funded by the U.S. Ambassador's Fund for Cultural Preservation, the Himalayan Wildlife Foundation was able, starting in 2004, to take the first important steps of documenting the structure and layout of the palace, while carrying out a topographic survey of the area. After constructing scaffolding and walkways to allow safe access to the site, emergency consolidation of decaying parts of the ground floor of the haveli were com- pleted. Damaged floors, walls and shades on the upper floors were repaired with lime plaster. Soil erosion in the courtyard allowed rainwater to seep into the ground floor; that problem was resolved so that water does not accu- mulate. The restorers also had to contend with tufts of grass and even a tree penetrating the walls. The expand- ing tree trunk caused part of the base of the cupola's drum to separate from the structure. Two original motifs encircling the cupola were dis- covered as workers stripped away damaged and decayed mortar; they have been restored, as well as the brick design on part of the rim. This allows viewers to get an idea of what the original design looked like. -

AFCP Projects at World Heritage Sites

CULTURAL HERITAGE CENTER – BUREAU OF EDUCATIONAL AND CULTURAL AFFAIRS – U.S. DEPARTMENT OF STATE AFCP Projects at World Heritage Sites The U.S. Ambassadors Fund for Cultural Preservation supports a broad range of projects to preserve the cultural heritage of other countries, including World Heritage sites. Country UNESCO World Heritage Site Projects Albania Historic Centres of Berat and Gjirokastra 1 Benin Royal Palaces of Abomey 2 Bolivia Jesuit Missions of the Chiquitos 1 Bolivia Tiwanaku: Spiritual and Political Centre of the Tiwanaku 1 Culture Botswana Tsodilo 1 Brazil Central Amazon Conservation Complex 1 Bulgaria Ancient City of Nessebar 1 Cambodia Angkor 3 China Mount Wuyi 1 Colombia National Archeological Park of Tierradentro 1 Colombia Port, Fortresses and Group of Monuments, Cartagena 1 Dominican Republic Colonial City of Santo Domingo 1 Ecuador City of Quito 1 Ecuador Historic Centre of Santa Ana de los Ríos de Cuenca 1 Egypt Historic Cairo 2 Ethiopia Fasil Ghebbi, Gondar Region 1 Ethiopia Harar Jugol, the Fortified Historic Town 1 Ethiopia Rock‐Hewn Churches, Lalibela 1 Gambia Kunta Kinteh Island and Related Sites 1 Georgia Bagrati Cathedral and Gelati Monastery 3 Georgia Historical Monuments of Mtskheta 1 Georgia Upper Svaneti 1 Ghana Asante Traditional Buildings 1 Haiti National History Park – Citadel, Sans Souci, Ramiers 3 India Champaner‐Pavagadh Archaeological Park 1 Jordan Petra 5 Jordan Quseir Amra 1 Kenya Lake Turkana National Parks 1 1 CULTURAL HERITAGE CENTER – BUREAU OF EDUCATIONAL AND CULTURAL AFFAIRS – U.S. DEPARTMENT -

Punjab Tourism for Economic Growth Final Report Consortium for Development Policy Research

Punjab Tourism for Economic Growth Final Report Consortium for Development Policy Research ABSTRACT This report documents the technical support provided by the Design Team, deployed by CDPR, and covers the recommendations for institutional and regulatory reforms as well as a proposed private sector participation framework for tourism sector in Punjab, in the context of religious tourism, to stimulate investment and economic growth. Pakistan: Cultural and Heritage Tourism Project ---------------------- (Back of the title page) ---------------------- This page is intentionally left blank. 2 Consortium for Development Policy Research Pakistan: Cultural and Heritage Tourism Project TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ACRONYMS & ABBREVIATIONS 56 LIST OF FIGURES 78 LIST OF TABLES 89 LIST OF BOXES 910 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 1011 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1112 1 BACKGROUND AND CONTEXT 1819 1.1 INTRODUCTION 1819 1.2 PAKISTAN’S TOURISM SECTOR 1819 1.3 TRAVEL AND TOURISM COMPETITIVENESS 2324 1.4 ECONOMIC POTENTIAL OF TOURISM SECTOR 2526 1.4.1 INTERNATIONAL TOURISM 2526 1.4.2 DOMESTIC TOURISM 2627 1.5 ECONOMIC POTENTIAL HERITAGE / RELIGIOUS TOURISM 2728 1.5.1 SIKH TOURISM - A CASE STUDY 2930 1.5.2 BUDDHIST TOURISM - A CASE STUDY 3536 1.6 DEVELOPING TOURISM - KEY ISSUES & CHALLENGES 3738 1.6.1 CHALLENGES FACED BY TOURISM SECTOR IN PUNJAB 3738 1.6.2 CHALLENGES SPECIFIC TO HERITAGE TOURISM 3940 2 EXISTING INSTITUTIONAL ARRANGEMENTS & REGULATORY FRAMEWORK FOR TOURISM SECTOR 4344 2.1 CURRENT INSTITUTIONAL ARRANGEMENTS 4344 2.1.1 YOUTH AFFAIRS, SPORTS, ARCHAEOLOGY AND TOURISM -

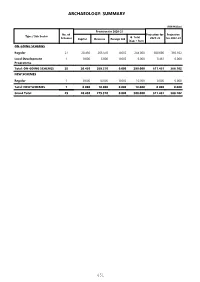

Archaeology: Summary

ARCHAEOLOGY: SUMMARY (PKR Million) Provision for 2020-21 No. of Projection for Projection Type / Sub Sector G. Total Schemes Capital Revenue Foreign Aid 2021-22 for 2022-23 (Cap + Rev) ON-GOING SCHEMES Regular 27 20.430 263.570 0.000 284.000 608.000 366.102 Local Development 1 0.000 6.000 0.000 6.000 3.461 0.000 Programme Total: ON-GOING SCHEMES 28 20.430 269.570 0.000 290.000 611.461 366.102 NEW SCHEMES Regular 1 0.000 10.000 0.000 10.000 0.000 0.000 Total: NEW SCHEMES 1 0.000 10.000 0.000 10.000 0.000 0.000 Grand Total 29 20.430 279.570 0.000 300.000 611.461 366.102 451 Archaeology (PKR Million) Accum. Provision for 2020-21 MTDF Projections Throw fwd GS Scheme Information Est. Cost Exp. G.Total Beyond No Scheme ID / Approval Date / Location Cap. Rev. 2021-22 2022-23 June, 20 (Cap.+Rev.) June, 2023 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 ON-GOING SCHEMES Regular 3859 Development and Restoration of 150.299 142.984 0.000 7.315 7.315 0.000 0.000 0.000 Archaeological Sites from Taxila to Swat (Taxila Section), Rawalpindi 01291200016 / 01-07-2012 / Rawalpindi 3860 Improvement and Up-gradation of Taxila 15.607 13.357 0.000 2.250 2.250 0.000 0.000 0.000 Museum 01291604472 / 29-08-2016 / Rawalpindi 3861 Conservation and Restoration of Losar 21.000 1.910 0.000 5.000 5.000 14.090 0.000 0.000 Boali, Wah Cantt, 01291901438 / 21-08-2019 / Rawalpindi 3862 Master Plan for Preservation and 218.094 154.419 0.000 10.000 10.000 27.000 26.675 0.000 Restoration of Rohtas Fort, Jhelum, 01281200011 / 01-07-2012 / Jhelum 3863 Development of Rothas Fort Distt 38.572 19.282 0.000 -

Estimates of Charged Expenditure and Demands for Grants (Development)

GOVERNMENT OF THE PUNJAB ESTIMATES OF CHARGED EXPENDITURE AND DEMANDS FOR GRANTS (DEVELOPMENT) VOL - II (Fund No. PC12037 – PC12043) FOR 2011 - 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS Demand # Description Pages VOLUME-I PC22036 Development 1 - 720 VOLUME-II PC12037 Irrigation Works 1 - 40 PC12038 Agricultural Improvement and Research 41 - 45 PC12040 Town Development 47 - 52 PC12041 Roads and Bridges 53 - 171 PC12042 Government Buildings 173 - 399 PC12043 Loans to Municipalities / Autonomous Bodies, etc. 401 - 411 GOVERNMENT OF THE PUNJAB GENERAL ABSTRACT OF DISBURSEMENT (GROSS) (Amount in million) Budget Revised Budget Estimates Estimates Estimates 2010-2011 2010-2011 2011-2012 PC22036 Development 100,099.054 81,431.616 127,207.412 PC12037 Irrigation Works 10,638.747 8,071.528 10,891.000 PC12038 Agricultural Improvement and Research 145.865 146.554 124.087 PC12040 Town Development 650.000 287.491 1,200.000 PC12041 Roads and Bridges 49,781.208 37,985.865 38,251.976 PC12042 Government Buildings 34,700.126 10,844.478 42,325.525 PC12043 Loans to Municipalities/Autonomous Bodies etc. 11,531.739 8,468.178 10,987.138 TOTAL :- 207,546.739 147,235.710 230,987.138 Current / Capital Expenditure detailed below: Daanish School System (3,000.000) - (3,000.000) Punjab Education Endowment Fund (PEEF) - - (2,000.000) Punjab Education Foundation (PEF) - - (6,000.000) TEVTA - - (2,000.000) DLIs for MDGs - - (8,500.000) Town Development (650.000) (287.491) (1,200.000) Population Welfare Programme (1,865.000) (1,341.127) (2,860.000) Companies: FIEDMC, PLDC, SWM, PLDDB, - - (6,440.000) PARB etc Current Capital Expenditure (11,531.739) (8,468.178) (10,987.138) Total (17,046.739) (10,096.796) (42,987.138) Net Annual Development Programme 190,500.000 137,138.914 188,000.000 BUDGET ESTIMATES REVISED ESTIMATES BUDGET ESTIMATES Page # GRANT/SECTOR/SUBSECTOR 2010‐11 2010‐11 2011‐12 SUMMARY Rs Rs Rs. -

STFP Bulletin

November 2012 Volume 1, Issue 11 STFP Bulletin STFP promotes tourism practices that are environmentally sustainable, economically beneficial to the local communities, and educational experience for tourists. Newsletter Highlights: Eco-Adventure trip to Cholistan Desert In the south of Punjab along the border of India lies the mysterious desert of Cholistan. This vast dry expanse holds in its heart a treasure of historical sites, cultural heritage and rich Eco-Adventure trip to variety of wild life. Cholistan Desert 1 The desert of Cholistan was once the lush green valley of great Hakra River which suddenly disappeared about 4000 years ago and with it went the glory of this land. The jungles Day trip to Rawat Fort vanished, wildlife migrated and civilization living along its banks moved on to the fertile banks of Indus River. and Rohtas Fort 2 Day trip to Thatta, Through this tour we will take you to Cholistan desert at the time of the year when its landscape looks its best and you will get a chance to explore the hidden grandeur of the vast Makli, Haleji and wilderness of this magical desert. You will visit desert villages, nomadic settlements, shrines of sufi saints, Lalsohanra National Park and remains of the old fort of Derawar. Keenhar Lakes 3 Date: 8 to 11 November What is Sustainable Day: Thursday to Sunday Tourism? 4 Duration: 4 days Isn’t Sustainable Departure Time: 0800 hours Base: Lahore Tourism the same thing Per head Fee: Rs.11,900/- as Eco-Tourism? 4 Booking Deadline: 5th November To register for this trip please send us an email at: [email protected] Upcoming Events 4 For further information contact: Syed Adnan Amjad at 051-2612448,Rauf Ahmad 0300- 4550435 STFP Bulletin Page 2 of 4 Day trip to Rawat Fort and Rohtas Fort Rohtas Fort is a symbol of the determination and strength of its builder, Sher Shah Suri. -

Conserving Pa Kis Ta N

CONSERVING PAK I S TA N ’ S B U I LT H E R I TA G E Fauzia Qureshi ENVIRONMENT & URBAN AFFAIRS DIVISION, GOVERNMENT OF PAKISTAN The sector papers were commissioned from mid-1988 to mid-1990 and printed in 1992, 1993 and 1994 The Pakistan National Conservation Strategy was prepared by the Government of Pakistan (Environment and Urban Affairs Division) in collaboration with IUCN – The World Conservation Union It was supported by the Canadian International Development Agency Additional sector activities were supported by the United Nations Development Programme IUCN – The World Conservation Union, Pakistan 1 Bath Island Road, Karachi 75530 © 1994 by IUCN – The World Conservation Union, Pakistan All rights reserved This material can be copied without the prior permission of the publisher Editors: Tehmina Ahmed & Yasmin Qureshi Editorial Advisors: Dhunmai Cowasjee & Saneeya Hussain ISBN 969-8141-01-4 Design: Creative Unit (Pvt) Ltd Formatting: Umer Gul Afridi, Journalists' Resource Centre for the Environment Printed in Pakistan by Rosette CONTENTS ● ● ● ● ● ● ● Acknowledgments vii Preface ix Summary xi 1. Introduction 1 2. Scope of Study 2 3. Background and Current Status 2 Background 2 The Current Situation 3 4. Problems Affecting the Built Heritage 6 Neglect 6 Poor Quality Conservation Work 8 Rapid Urbanization 9 Pollution 9 Natural Disasters 10 5. Resolving the Problems 11 Urbanization 11 Pollution 11 iii Generating Revenue 11 Incentives for Conservation 12 Legislation 13 Increase in Trained Manpower 13 Awareness Campaign 14 Conservation as a Means of Education 14 Tourism 15 6. Policy Recommendations for Heritage Conservation 15 Building Awareness 15 Training Programmes 17 An Inventory of the Built Heritage 17 Co-ordination 18 Legislation and Administration 18 Tourism Promotion and Development 18 Economic Instruments (Incentives and Penalties) 19 7. -

Mughal Architecture Period

www.gradeup.co Mughal dynasty was established after the battle of Panipat in 1526. And after Babur, every emperor took great considerable interest in the architecture field. The Mughals were a staunch supporter of art and architecture. They developed Indo-Islamic architecture in the Indian subcontinent. They developed or improve the style of earlier dynasties like Lodhi’s and it was a combination of Islamic, Persian, Turkish and Indian Architecture. During this reign, architecture touched its zenith, many new buildings and tombs were built with great artistic vision and inspiration. Mughal Architecture Period BABUR • Babur undertook the construction of a mosque in Panipat and Rohilkhand in 1526 A.D. • His reign was too small for any new style and design but he was fond of formal gardens. HUMAYUN • He succeeded Babur but the reign was filled with constant struggle and war with Sher Shah Suri. • He led the foundation of a city named Dinpanah but he couldn’t finish it. • The first proper Mughal architecture was Humayun’s Tomb in Delhi, built by his widow Hamida Bhanu Begum. Also known as a precursor of Taj Mahal in Agra and provided the prototype for Mausoleum of Jahangir at Shahdara, Lahore. • Persian style was prominent during this period. • Sikandar Lodhi’s Tomb was the first garden-tomb built in India but it was the Humayun’s Tomb which gave new vision to art. • Some of the designing features were: o The tomb stands on a raised vast platform in the centre of a square garden. o Garden is divided into 4 parts by Charbagh (causeways), in the centre of which run shallow water-channels. -

Part 8 of 9 of the Main Report

Environmental Impact Assessment July 2017 PAK: Jalalpur Irrigation Project Project No. 46528-002 Part 8 of 9 of the Main Report Prepared by Irrigation Department, Government of Punjab for the Asian Development Bank (ADB). This environmental impact assessment is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. ADB PDA 6006: PAK Detailed Design of Jalalpur Irrigation Project Environmental Impact Assessment (Updated) CHAPTER-7 STAKEHOLDER CONSULTATION 7.1. Introduction 393. The basic purpose of conducting the stakeholder consultation was to involve the key stakeholders and locals into the process of Project design and to incorporate the appropriate environmental and social concerns into the process. Moreover, Pak-EPA’s IEE/EIA Regulations specify that the stakeholder consultation process shall be an integral part of environmental assessment, and thus makes it mandatory. This Chapter presents the details of the stakeholder consultation process carried out for the proposed Project. Consultations which were initiated at the Project preparatory/feasibility stage for the EIA were continued at the detailed design stage. 394. Stakeholders of the Project were identified, categorized and accessed at selected federal, provincial, district and village levels (including those who will be directly and indirectly affected by the Project). -

Pakistan Autumn Sightseeing Tour

Pakistan Autumn Sightseeing Tour Tour Highlights • Karakoram Highway –Old Silk Route • Eye-Catching Beauty of Nanga Parbat-8125m • Famous Indus River & visit Junction of Karakoram, Himalaya, Hindukush • Hunza Valley and views of snowcapped Rakaposhi 7788m • Explore Kalash valleys of Chitral • Famous Passes- Khunjerab, Shandoor and Lowari Explore All Provinces by driving through Besham,Islamabad, Lahore, Multan, Sukkur 20 NIGHTS HOTEL, 21 DAYS US$1100/PAX FOR A GROUP OF 12 SIGHTSEEING US$ 1200/PAX FOR A GROUP OF 10 SOFT HIKING US$1350/PAX FOR A GROUP OF 8-9 MAX. ALTITUDE – 4733M / 15,528FT US$1450/PAX FOR A GROUP OF 5-7 Key Destinations: Lahore - Islamabad- Karakoram Highway - Gilgit- Hunza Khunjerab Pass- Ghizer Valley- Shandoor Pass-Chitral-Kalash Valley-Lowari Pass www.snowland.com.pk PK: +92(0)3335105022 [email protected] 2 | Page Pakistan Autumn Sightseeing Tour TOUR BACKGROUND This exciting tour will take you to the dramatic and enchanting valleys of the Northern Areas (Gilgit-Baltistan & Chitral) of Pakistan. Lush green fertile valleys with high quality delicious fruit are fed by springs and glacial streams flowing from the lofty snow capped mountains. Karakoram Highway and River Indus is a constant Feature of the region. The best time of year to visit Hunza and Chitral is April to October. From spring to autumn the valleys are more attractive, all three fabulous seasons have their own unique charm, which cannot be described in words but can only be felt. TOUR OVERVIEW DEPARTURE DATES: April- November 2018 Date Day Activity -

Psdp 2009-2010

WATER & POWER DIVISION (WATER SECTOR) (Million Rupees) Sl. Name, Location & Status of the Estimated Cost Expenditure Throw- Allocation for 2009-10 No Scheme Total Foreign upto June forward as on Foreign Rupee Total Loan 2009 01-7-09 Loan 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 On-going Schemes 1 Raising of Mangla Dam including 101384.330 0.000 62204.003 39180.327 0.000 12000.000 12000.000 resettlement 2 Mirani Dam 5811.000 0.000 5247.260 563.740 0.000 313.740 313.740 3 Sabakzai Dam 2005.545 0.000 1488.990 516.555 0.000 280.000 280.000 4 Satpara Multipurpose Dam 4805.975 195.786 2193.998 2611.977 0.000 50.000 50.000 5 Gomal Zam Dam 12829.000 4964.000 2951.922 9877.078 0.000 2000.000 2000.000 6 Greater Thal Canal (Phase - I) 30467.109 0.000 7176.962 23290.147 0.000 1000.000 1000.000 7 Kachhi Canal (Phase - I) 31204.000 0.000 18625.016 12578.984 0.000 4000.000 4000.000 8 Rainee Canal (Phase - I) 18862.000 0.000 5051.287 13810.713 0.000 2000.000 2000.000 9 Lower Indus Right Bank Irrigation & 14707.143 0.000 10819.677 3887.466 0.000 1500.000 1500.000 Drainage, Sindh 10 Balochistan Effluent Disposal into RBOD. 6535.970 0.000 2548.353 3987.617 0.000 800.000 800.000 (RBOD-III) 11 Feasibility Studies of Dams (Naulong, 378.468 0.000 191.485 186.983 0.000 60.000 60.000 Hingol), Balochistan 12 Land and Water Monitoring / Evaluation 427.000 0.000 0.000 427.000 0.000 40.000 40.000 of Indus Plains (SMO) 13 Construction of IRSA Office building, 38.250 0.000 28.250 10.000 0.000 10.000 10.000 Islamabad 14 Revamping/Rehabilitation of Irrigation & 16796.000 0.000 8850.000 7946.000 -

ISLAMABAD to KARACHI (17 Days) Domes & Deserts of the Indus

ISLAMABAD to KARACHI (17 days) Domes & Deserts of the Indus COUNTRIES VISITED: PAKISTAN INCLUDES • Accommodation - twin share - simple hostels/hotels • Islamabad city tour • Taxila museum • Shan Faisal Mosque • Rohtas Fort • Lahore city tour (2 full days) • Harappa archaeological site • Multan city tour • Derawar Fort • Sadu Bela - Hindu Temple • Boat safari to Sukkur island • Boating with the Mohanas tribe on Manchar Lake • Ajrak factory visit (traditional block printed cloth) • Karachi city and surroundings tour (1 full day) www.oasisoverland.co.uk PAGE 1 [email protected] Tel: +44 (0)203 725 8924 • Manghopir Sufi Shrine and hot sulphur springs • Letter of Invitation and general visa advice • Pakistani clothes (Shalwaar Chemise) • Airport transfers • Meals - 3 meals per day • Tea & Coffee morning & afternoon • All transport • English speaking guide EXCLUDES • Visas • Optional Excursions as listed in the Pre-Departure Information • Flights • Airport Taxes & Transfers • Travel Insurance • Drinks • Tips TRIP ITINERARY DAYS 1 ISLAMABAD Welcome in Pakistan at Islamabad airport. Transfer to our hotel and take a rest before starting with our city tour. Islamabad is a city of many contrasts with green avenues, splendid views of the surrounding hills and busy city life. We have a full day's guided tour around the major sights, including the old city of Rawalpindi, Daman e Koh view point and the huge structure of Shah Faisal Mosque. A short drive away is the museum of Taxila and the remains of Jaulian Monastery. We have time to browse in the museum at the artefacts, many dating back over 2000 years. DAYS 2 - 4 ISLAMABAD TO LAHORE En route to Lahore we visit the Rohtas Fort.