"On the Other Side of Sorrow" by James Hunter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sutherland Futures-P22-24

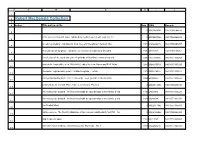

THINGS YOU NEED TO NOTE ALTNAHARRA, OUTLYING TOWNSHIPS INCHNADAMPH, FORSINARD Reinforcing rural townships where development is consistent with the pattern of AND KINBRACE settlement, service capacity and local amenity is encouraged. Central South and East North West Achnahannat Achuan Achlyness Several traditional staging posts within the remote and sparsely populated Achnairn Achavandra Muir Achmelvich interior continue to offer lifeline services in remote, fragile communities. Altass Achrimsdale-East Achnacarin Prospects are dependent on sustained employment in estate/land management, Amat Clyne Achriesgill (east and tourism and interpretive facilities and local enterprise. Development pressures Astle Achue west) are negligible. Given a lack of first-time infrastructure, a flexible development Linside Ardachu Badcall regime needs to balance safeguards for the existing character and environmental Linsidemore Backies Badnaban standards. Migdale Badnellan Balchladich Spinningdale Badninish Blairmore Camore Clachtoll Clashbuidh Clashmore What key sites are most suitable? What key sites North are least suitable? Does the Settlement Clashmore Clashnessie Achininver Crakaig Crofts- Culkein Development Area suitably reflect the limits of Baligill Lothmore Culkein of Drumbeg ?? your community for future development? Blandy/Strathtongue ??? Crofthaugh Droman Braetongue/ Brae Culgower-West Garty Elphin What development or facilities does your Kirkiboll Lodge Foindle Clerkhill community need and where? Culrain Inshegra Coldbackie Dalchalm Inverkirkaig -

The Norse Influence on Celtic Scotland Published by James Maclehose and Sons, Glasgow

i^ttiin •••7 * tuwn 1 1 ,1 vir tiiTiv^Vv5*^M òlo^l^!^^ '^- - /f^K$ , yt A"-^^^^- /^AO. "-'no.-' iiuUcotettt>tnc -DOcholiiunc THE NORSE INFLUENCE ON CELTIC SCOTLAND PUBLISHED BY JAMES MACLEHOSE AND SONS, GLASGOW, inblishcre to the anibersitg. MACMILLAN AND CO., LTD., LONDON. New York, • • The Macmillan Co. Toronto, • - • The Mactnillan Co. of Canada. London, • . - Simpkin, Hamilton and Co. Cambridse, • Bowes and Bowes. Edinburgh, • • Douglas and Foults. Sydney, • • Angus and Robertson. THE NORSE INFLUENCE ON CELTIC SCOTLAND BY GEORGE HENDERSON M.A. (Edin.), B.Litt. (Jesus Coll., Oxon.), Ph.D. (Vienna) KELLY-MACCALLUM LECTURER IN CELTIC, UNIVERSITY OF GLASGOW EXAMINER IN SCOTTISH GADHELIC, UNIVERSITY OF LONDON GLASGOW JAMES MACLEHOSE AND SONS PUBLISHERS TO THE UNIVERSITY I9IO Is buaine focal no toic an t-saoghail. A word is 7nore lasting than the world's wealth. ' ' Gadhelic Proverb. Lochlannaich is ànnuinn iad. Norsemen and heroes they. ' Book of the Dean of Lismore. Lochlannaich thi'eun Toiseach bhiir sgéil Sliochd solta ofrettmh Mhamiis. Of Norsemen bold Of doughty mould Your line of oldfrom Magnus. '' AIairi inghean Alasdair Ruaidh. PREFACE Since ever dwellers on the Continent were first able to navigate the ocean, the isles of Great Britain and Ireland must have been objects which excited their supreme interest. To this we owe in part the com- ing of our own early ancestors to these isles. But while we have histories which inform us of the several historic invasions, they all seem to me to belittle far too much the influence of the Norse Invasions in particular. This error I would fain correct, so far as regards Celtic Scotland. -

Contemporary Gaelic Language and Culture: an Introduction (SCQF Level 5)

National Unit specification: general information Unit title: Contemporary Gaelic Language and Culture: An Introduction (SCQF level 5) Unit code: FN44 11 Superclass: FK Publication date: July 2011 Source: Scottish Qualifications Authority Version: 01 Summary The purpose of this Unit is to provide candidates with the knowledge and skills to enable them to understand development issues relating to the Gaelic language; understand contemporary Gaelic media, performing arts and literature; and provide the opportunity to enhance the four language skills of speaking, listening, reading and writing. This is a mandatory Unit within the National Progression Award in Contemporary Gaelic Songwriting and Production but can also be taken as a free-standing Unit. This Unit is suitable both for candidates who are fluent Gaelic speakers or Gaelic learners who have beginner level skills in written and spoken Gaelic. It can be delivered to a wide range of learners who have an academic, vocational or personal interest in the application of Gaelic in the arts and media. It is envisaged that candidates successfully completing this Unit will be able to progress to further study in Gaelic arts. Outcomes 1 Describe key factors contributing to Gaelic language and cultural development. 2 Describe key elements of the contemporary Gaelic arts and media world. 3 Apply Gaelic language skills in a range of contemporary arts and media contexts. Recommended entry While entry is at the discretion of the centre, candidates are expected to have, as a minimum, basic language skills in Gaelic. This may be evidenced by the attainment of Intermediate 1 Gaelic (Learners) or equivalent ability in the four skills of listening, speaking, reading and writing. -

On the Study and Promotion of Drama in Scottish Gaelic Sìm Innes

Editorial: On the study and promotion of drama in Scottish Gaelic Sìm Innes (University of Glasgow) and Michelle Macleod (University of Aberdeen), Guest-Editors We are very grateful to the editors of the International Journal of Scottish Theatre and Screen for allowing us the opportunity to guest-edit a special volume about Gaelic drama. The invitation came after we had organised two panels on Gaelic drama at the biennial Gaelic studies conference, Rannsachadh na Gàidhlig, at the University Edinburgh 2014. We asked the contributors to those two panels to consider developing their papers and submit them to peer review for this special edition: each paper was read by both a Gaelic scholar and a theatre scholar and we are grateful to them for their insight and contributions. Together the six scholarly essays and one forum interview in this issue are the single biggest published work on Gaelic drama to date and go some way to highlighting the importance of this genre within Gaelic society. In 2007 Michelle Macleod and Moray Watson noted that ‘few studies of modern Gaelic drama’ (Macleod and Watson 2007: 280) exist (prior to that its sum total was an unpublished MSc dissertation by Antoinette Butler in 1994 and occasional reviews): Macleod continued to make the case in her axiomatically entitled work ‘Gaelic Drama: The Forgotten Genre in Gaelic Literary Studies’. (Dymock and McLeod 2011) More recently scholarship on Gaelic drama has begun to emerge and show, despite the fact that it had hitherto been largely neglected in academic criticism, that there is much to be gained from in-depth study of the genre. -

Review of the Sutherland Biodiversity Action Plan 2003 – 2012

Review of the Sutherland Biodiversity Action Plan 2003 – 2012 A report to the Sutherland Partnership Biodiversity Group by Ro Scott March 2013 1 Contents Page Highlights – A selection of successful projects 3 1. Introduction 4 2. Analysis of projects 5 3. Evaluation against original objectives 8 4. Changes since 2003 10 5. Identification of achievement gaps and the means to fill them 14 6. Cross-cutting issues 34 7. Where to next? 36 8. Miscellaneous recommendations 38 Throughout the document, direct quotes from the original 2003 Sutherland Biodiversity Action Plan are shown in a smaller typeface. Acknowledgement Thanks are due to all the current members of the Sutherland Partnership Biodiversity Group for their enthusiastic input to this review: Ian Evans (Chair) Assynt Field Club Kate Batchelor West Sutherland Fisheries Trust Janet Bromham Highland Council Biodiversity Officer Paul Castle Highland Council Ranger Service Judi Forsyth SEPA Kenny Graham RSPB Fiona Mackenzie Sutherland Partnership Development Officer Ian Mitchell SNH Don O’Driscoll John Muir Trust Andy Summers Highland Council Ranger Service Gareth Ventress Forest Enterprise Scotland 2 Ten Years of the Sutherland Biodiversity Action Plan *** Highlights *** (in no particular order) 230 populations of Aspen identified with suggestions for further work Important new habitat type recognised and located – Ancient Wood Pasture Information on three key groups of Sutherland invertebrates collated Two village wildlife audits published – Scourie and Rogart 9 Primary Schools engaged in conservation projects Two new wildlife ponds created New water vole colonies discovered Wildflower meadow created at Golspie Two ‘Wet and Wild’ weekends held at Borgie and Kinlochbervie Nesting terns protected on Brora Golf Course First confirmed British record of the lacewing Helicoconis hirtinervis 3 1. -

Reconstruction of a Gaelic World in the Work of Neil M. Gunn and Hugh Macdiarmid

Paterson, Fiona E. (2020) ‘The Gael Will Come Again’: Reconstruction of a Gaelic world in the work of Neil M. Gunn and Hugh MacDiarmid. MPhil(R) thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/81487/ Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten: Theses https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] ‘The Gael Will Come Again’: Reconstruction of a Gaelic world in the work of Neil M. Gunn and Hugh MacDiarmid Fiona E. Paterson M.A. (Hons) Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Philosophy in Scottish Literature School of Critical Studies College of Arts University of Glasgow June 2020 Abstract Neil Gunn and Hugh MacDiarmid are popularly linked with regards to the Scottish Literary Renaissance, the nation’s contribution to international modernism, in which they were integral figures. Beyond that, they are broadly considered to have followed different creative paths, Gunn deemed the ‘Highland novelist’ and MacDiarmid the extremist political poet. This thesis presents the argument that whilst their methods and priorities often differed dramatically, the reconstruction of a Gaelic world - the ‘Gaelic Idea’ - was a focus in which the writers shared a similar degree of commitment and similar priorities. -

SSC 2011 Brochure Concept 4.Indd

Scottish International Storytelling Festival 2011 An Island Odyssey: Scotland and Old Europe 21 October – 30 October Box offi ce: 0131 556 9579 www.scottishstorytellingcentre.co.uk Welcome to the About the programme Scottish International Each event in our programme is categorised to help you decide which to book. The two main strands are for adults, and take place in Edinburgh and Storytelling Festival on tour across Scotland, with an emphasis this year on Scotland’s islands. Welcome to a feast of Thon places hae the uncanny knack o a dh’fhiosraich sinn. Uime sin, Live Storytelling concluding with a fi nale where the island culture – Scottish and makin oor speerits rise an oor thochts èisdibh ri luasgadh nan tonn, Live evening storytelling whole story and its epic themes of Mediterranean. There is bizz wi tales, tunes and dauncin fi t. teudan na clàrsaich agus guth an performances in the Scottish temptation, separation and journey something about islands that We’re aa isalnders at hert, sae harken sgeulaiche fad an deich an latha Storytelling Centre’s stunning, are explored in a grand afternoon catches our imagination, gives noo tae the shush of the sea, the birr seo de chèilidh agus ealainean intimate theatre space and at and evening of unforgettable birth to stories, inspires melody o strings, and the voice o the tellers tradaiseanta. Togaibh an acair The Hub, headquarters of the storytelling. and sometimes sets the foot an the makars. Louse the tows an agus seòlaibh a-mach ann am Edinburgh International Festival. tapping. There is something drift oan a dwamming tide. -

Northern Scotland

Soil Survey of Scotland NORTHERN SCOTLAND 15250 000 SHEET 3 The Macaulay Institute for Soil Research Aberdeen 1982 SOIL SURVEY OF SCOTLAND Soil and Land Capability for Agriculture NORTHERN SCOTLAND By D. W. Futty, BSc and W. Towers, BSc with contributions by R. E. F. Heslop, BSc, A. D. Walker, BSc, J. S. Robertson, BSc, C. G. B. Campbell, BSc, G. G. Wright, BSc and J. H. Gauld, BSc, PhD The Macaulay Institute for Soil Research Aberdeen 1982 @ The Macaulay Institute for Soil Research, Aberdeen, 1982 Front cover. CanGP, Suiluen and Cu1 Mor from north of Lochinuer, Sutherland. Hills of Tomdonian sandsione rise above a strongly undulating plateau of Lewirian gneiss. Institute of Geologcal Sciences photograph published by permission of the Director; NERC copyight. ISBN 0 7084 0221 6 PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS ABERDEEN Contents Chapter Page PREFACE vii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ix 1 DE~CRIPTIONOF THE AREA 1 PHYSIOGRAPHIC REGIONS- GEOLOGY, LANDFORMS AND PARENT MATERIALS 1 The Northern Highlands 1 The Grampian Highlands 5 The Caithness Plain 6 The Moray Firth Lowlands 7 CLIMATE 7 Rainfall and potential water deficit 8 Accumulated temperature 9 Exposure 9 SOILS 10 General aspects 10 Classification and distribution 12 VEGETATION 15 Moorland 16 Oroarctic communities 17 Grassland 18 Foreshore and dunes 19 Saltings and splash zone 19 Scrub and woodland 19 2 THE SOIL MAP UNITS 21 The Alluvial Soils 21 The Organic Soils 28 The Aberlour Association 31 The Ardvanie Association 32 The Arkaig Association 33 The Berriedale Association 44 The -

Robert Macdonald Collection 3 4 Author Title, Part No

A B C D E F 1 2 Robert MacDonald Collection 3 4 Author Title, part no. & title Date ISBN Barcode 0 M0019855HL 38011050264616 5 51 beauties of Scottish song : adapted for medium voices with tonic sol-fa / 0 M0006030HL 38011050265076 6 A Celtic miscellany : translations from the Celtic literatures / Kenneth Hur 1971 0140442472 38011050265357 7 A chuidheachd mo ghaoil : laoidean / air an seinn le Cairstiona Sheadha 1990 q8179317 38011050265662 8 A collection of the vocal airs of the Highlands of Scotland : communicated a 1996 1871931665 38011551310264 9 Acts of the Lords ofthe Isles 1336-1493 / edited by Jean Munro and R.W. Munr 1986 0906245079 38011551867255 10 Amannan : sgialachdan goimi / Pòl MacAonghais ... (et al.) 1979 055021402x 38011551310512 11 Am feachd Gaidhealach : ar tir 's ar teanga : lean gu dlùth ri cliù do shinn 1944 w3998157 38011551310850 12 A Mini-Guide to Cornish. Place Names, Dictionary, Phrases 0 M0023438HL 38011050270191 13 Am measg nam bodach : co-chruinneachadh de sgeulachdan is beul-aithris a cha 1938 q3349594 38011551310421 14 Am measg nam bodach : co-chruinneachadh de sgeulachdan is beul-aithris a cha 1938 q3349594 38011551311031 15 [An Dealbh Mhor] 0 M0023413HL 38011551315883 16 An Deo Greine. The Monthly Magazine of An Comunn Gaidhealach. Vol.XV1, No. 0 M0021209HL 38011050266405 17 And it came to pass 1962 b6219267 38011551865341 18 An Inverness miscellany / [edited by Loraine Maclean]. - No.1 1983 0950261238 38011551866331 19 A B C D E F An Inverness miscellany / [edited by Loraine Maclean]. - No.2 1987 0950261262 38011551866349 20 An Leabhar mo`r = The great book of Gaelic / edited by Malcolm Maclean and T 2002 1841952494 38011551311411 21 AN ROSARNACH:AN CEATHRAMH LEABHARBOOK 4. -

The Freeliterary Magazine of the North

NorthwordsIssue 16 NowAutum 2010 A Passion For Assynt MANDY HAGGITH, PÀDRAIG MACAOIDH & ALASDAIR MACRAE on NORMAN MACCAIG’s love for the ‘most beautiful corner of the land’ Poems and stories from LESLEY HARRISON, JIM TAYLOR, JIM CARRUTH, PAUL BROWNSEY & many more Reviews of the best new Scottish Books including ROBERT ALAN JAMIESON, ANGUS PETER CAMPBELL & NEIL GUNN The FREE literary magazine of the North Extract by kind permission of the Oxfort Dictionary and Cormack’s & Crawford’s, Dingwall and Ullapool. Victor Frankenstein used electricity to animate his monster. William McGonagall was struck by lightning while walking from Dundee to Braemar. William Falkner wrote ‘As I lay Dying’ while working at a power plant. The Next Great Author clicks the ‘Save’ button. Electricity drifts through the circuits. Electricity: from the frog-twitchings of galvanism to modern domesticated electrons. For electricity under control, contact: Electrical, environmental and general services. Inverfarigaig, Loch Ness 07712589626 Boswell, being angry at her, threw the mutton chops out of the window. I ventured outside to see what Forres might offer a traveller. The main street was broad and fair though the brats on the street were impertinent. However they left off their games when we came upon a market, whereat they called out ‘Babalu, babalu!’ and ran among the crowd. I had not encountered this word before. A courteous woman explained it thus: somewhere in this place there is an object which you will desire, though you know not what it may be. A curious word, yet cogent. I am resolved to enter it into my Dictionary. -

Gaelic Society Collection 3 Publication Control Classmark Author Title, Part No

A B C D E F G H 1 2 Gaelic Society Collection 3 Publication Control Classmark Author Title, part no. & title Barcode 4 date number (Dewey) A B C. : ann teagasg Criosdiugh, nios achamaire do reir ceisd & 1838 q8179079 238 38011086142968 5 freagradh ai A' Charraig : leabhar bliadhnail eaglais bhearnaraigh 1971 0950233102 285.24114 38011030517448 6 A' Charraig : leabhar bliadhnail eaglais bhearnaraigh 1971 0950233102 285.24114 38011086358515 7 A' Charraig : leabhar bliadhnail eaglais bhearnaraigh 1971 0950233102 285.24114 38011086358523 8 A'Choisir-chiuil : the St.Columba collection of Gaelic songs arranged for 1983 0901771724 891.63 38011030517331 9 pa A'chòmdhail cheilteach eadarnàiseanta : Congress 99. - Glaschu : 26-31 2000 M0001353HL 891.63 38011000710015 10 July A collection of Highland rites and customes / copied by Edward Lhuyd 1975 0859910121 390.941 38011000004195 11 from th A collection of Highland rites and customes / copied by Edward Lhuyd 1975 0859910121 390.941 38011086392324 12 from th A collection of the vocal airs of the Highlands of Scotland : 1996 1871931665 788.95 38011086142927 13 communicated a A Companionto Scottish culture / edited by David Daiches 1981 0713163445 941.11 38011086393645 14 A History of the Scottish Highlands, Highland clans and Highland 1875 x3549092 941.15 38011086358366 15 regiments. Ainmean aìte = Place names 1991 095164193x 491.63 38011050956930 16 Ainmeil an eachraidh : iomradh air dusan ainmeil ann an caochladh 1997 1871901413 920.0411 38011097413804 17 sheòrsacha Aithghearradh teagasg Chriosta : le aonta nan Easbuig ro-urramach 1902 q8177241 232.954 38011086340042 18 Easbuig Ab A B C D E F G H Alba [map]. - 1:1,000,000 1972 M0003560HL 912 38011030517398 19 Albyn's anthology : or, a select collection of the melodies & local poetry p. -

Annual Report 2004/05

annual report 2004/05 www.bord-na-gaidhlig.org.uk 1 1. Highlights in Bòrd na Gàidhlig’s Year ............................................................................................. 2 2. Bòrd na Gàidhlig ..................................................................................................................................... 4 Objectives, Operational Plan and Funding Criteria .............................................................4 contents The Members ....................................................................................................................................5 3. Chairman’s Comments ......................................................................................................................... 8 4. Chief Executive’s Report ....................................................................................................................10 5. Bòrd Na Gàidhlig – The Second Year ...........................................................................................14 Partnership and Alliance ...........................................................................................................14 Gaelic Language Bill ...................................................................................................................16 Language Planning ....................................................................................................................18 The Community ...........................................................................................................................20