Turkish Airlines As a Soft Power Tool in the Context of Turkish Foreign Policy Orçun Selçuk Boğazġçġ University 2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

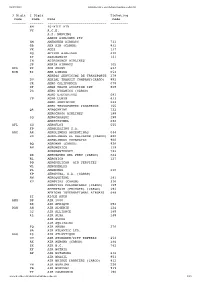

Appendix 25 Box 31/3 Airline Codes

March 2021 APPENDIX 25 BOX 31/3 AIRLINE CODES The information in this document is provided as a guide only and is not professional advice, including legal advice. It should not be assumed that the guidance is comprehensive or that it provides a definitive answer in every case. Appendix 25 - SAD Box 31/3 Airline Codes March 2021 Airline code Code description 000 ANTONOV DESIGN BUREAU 001 AMERICAN AIRLINES 005 CONTINENTAL AIRLINES 006 DELTA AIR LINES 012 NORTHWEST AIRLINES 014 AIR CANADA 015 TRANS WORLD AIRLINES 016 UNITED AIRLINES 018 CANADIAN AIRLINES INT 020 LUFTHANSA 023 FEDERAL EXPRESS CORP. (CARGO) 027 ALASKA AIRLINES 029 LINEAS AER DEL CARIBE (CARGO) 034 MILLON AIR (CARGO) 037 USAIR 042 VARIG BRAZILIAN AIRLINES 043 DRAGONAIR 044 AEROLINEAS ARGENTINAS 045 LAN-CHILE 046 LAV LINEA AERO VENEZOLANA 047 TAP AIR PORTUGAL 048 CYPRUS AIRWAYS 049 CRUZEIRO DO SUL 050 OLYMPIC AIRWAYS 051 LLOYD AEREO BOLIVIANO 053 AER LINGUS 055 ALITALIA 056 CYPRUS TURKISH AIRLINES 057 AIR FRANCE 058 INDIAN AIRLINES 060 FLIGHT WEST AIRLINES 061 AIR SEYCHELLES 062 DAN-AIR SERVICES 063 AIR CALEDONIE INTERNATIONAL 064 CSA CZECHOSLOVAK AIRLINES 065 SAUDI ARABIAN 066 NORONTAIR 067 AIR MOOREA 068 LAM-LINHAS AEREAS MOCAMBIQUE Page 2 of 19 Appendix 25 - SAD Box 31/3 Airline Codes March 2021 Airline code Code description 069 LAPA 070 SYRIAN ARAB AIRLINES 071 ETHIOPIAN AIRLINES 072 GULF AIR 073 IRAQI AIRWAYS 074 KLM ROYAL DUTCH AIRLINES 075 IBERIA 076 MIDDLE EAST AIRLINES 077 EGYPTAIR 078 AERO CALIFORNIA 079 PHILIPPINE AIRLINES 080 LOT POLISH AIRLINES 081 QANTAS AIRWAYS -

Die Folgende Liste Zeigt Alle Fluggesellschaften, Die Über Den Flugvergleich Von Verivox Buchbar Sein Können

Die folgende Liste zeigt alle Fluggesellschaften, die über den Flugvergleich von Verivox buchbar sein können. Aufgrund von laufenden Updates einzelner Tarife, technischen Problemen oder eingeschränkten Verfügbarkeiten kann es vorkommen, dass einzelne Airlines oder Tarife nicht berechnet oder angezeigt werden können. 1 Adria Airways 2 Aegean Airlines 3 Aer Arann 4 Aer Lingus 5 Aeroflot 6 Aerolan 7 Aerolíneas Argentinas 8 Aeroméxico 9 Air Algérie 10 Air Astana 11 Air Austral 12 Air Baltic 13 Air Berlin 14 Air Botswana 15 Air Canada 16 Air Caraibes 17 Air China 18 Air Corsica 19 Air Dolomiti 20 Air Europa 21 Air France 22 Air Guinee Express 23 Air India 24 Air Jamaica 25 Air Madagascar 26 Air Malta 27 Air Mauritius 28 Air Moldova 29 Air Namibia 30 Air New Zealand 31 Air One 32 Air Serbia 33 Air Transat 34 Air Asia 35 Alaska Airlines 36 Alitalia 37 All Nippon Airways 38 American Airlines 39 Arkefly 40 Arkia Israel Airlines 41 Asiana Airlines 42 Atlasglobal 43 Austrian Airlines 44 Avianca 45 B&H Airlines 46 Bahamasair 47 Bangkok Airways 48 Belair Airlines 49 Belavia Belarusian Airlines 50 Binter Canarias 51 Blue1 52 British Airways 53 British Midland International 54 Brussels Airlines 55 Bulgaria Air 56 Caribbean Airlines 57 Carpatair 58 Cathay Pacific 59 China Airlines 60 China Eastern 61 China Southern Airlines 62 Cimber Sterling 63 Condor 64 Continental Airlines 65 Corsair International 66 Croatia Airlines 67 Cubana de Aviacion 68 Cyprus Airways 69 Czech Airlines 70 Darwin Airline 71 Delta Airlines 72 Dragonair 73 EasyJet 74 EgyptAir 75 -

Antalya Airport 안탈리아 공항

Antalya Airport 안탈리아 공항 코 드 : AYT / LTAI 도 시 : Antalya / 안탈리아 국 가 : Turkey / 터키 기준일: 2008.12.31 ◎ 개요 ▶ 주소 : Havalimani Basmudurlugu TR-07030 Antalya Turkey ▶ 전화 : +90 242-330 33 01, 330 33 04 ▶ 팩스 : +90 242-330 33 02 ▶ 홈페이지 : http://www.aytport.com/index.htm ▶ 이메일 : [email protected] ◎ 공항운영자 Gen Directorate of State Airports Administration (DHMI), Havalimani 공항운영주체 Basmudurlugu, Antalya Airport, 07030 Antalya 전화 +90 242-330 33 01, 330 33 04 팩스 +90 242-330 33 02 ◎ 시설현황 Rwy 18L/36R, 11,155' 3,400 m, width 148' 45 m, concrete, PCN 80 활주로 R/A/X/T. 추가활주로 Rwy 18R/36L, 9,809' 2,990 m, width 148' 45 m, asphalt 최대활주로길이 11,155' 3,400m Rwy 18L: HIRL, PAPI. Rwy 18R: HIRL, VASI. 활주로 등화 Rwy 36L: HIRL, calvert, VASI. Rwy 36R: HIRL, calvert, PAPI. ILS/DME (Brg 003º, LLZ ID I-AYT, 110.3 MHz, Ch 40, GS 3.0º); VOR/DME (Antalya, ID AYT, 114.0 MHz, Ch 87, N36º55.28' E030º47.82', 188º, 1.2 nm); TACAN (Antalya, ID AYT, Ch 102, N36º54.93' E030º46.97', at field); DME (Antalya, ID ANT, Ch 28, N36º52.53' 항행시설 E030º47.35', 001º, 1.6 nm); NDB (Antalya, ID YT, 302 kHz, N36º52.57' E030º47.35', 002º, 1.5 nm; Antalya, ID GEY, 413 kHz, N36º52.57' E030º27.31', 081º, 16.3 nm). Frequencies: Twr 126.1, 257.8 MHz; Gnd 121.9 MHz; App 122.05, 128.3, 362.3 MHz; ATIS 118.275 MHz. 주파수 See Navaids. 인근도시 Antalya (13 km). -

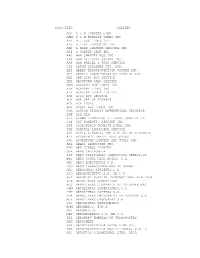

3 Digit 2 Digit Ticketing Code Code Name Code ------6M 40-MILE AIR VY A.C.E

06/07/2021 www.kovrik.com/sib/travel/airline-codes.txt 3 Digit 2 Digit Ticketing Code Code Name Code ------- ------- ------------------------------ --------- 6M 40-MILE AIR VY A.C.E. A.S. NORVING AARON AIRLINES PTY SM ABERDEEN AIRWAYS 731 GB ABX AIR (CARGO) 832 VX ACES 137 XQ ACTION AIRLINES 410 ZY ADALBANAIR 121 IN ADIRONDACK AIRLINES JP ADRIA AIRWAYS 165 REA RE AER ARANN 684 EIN EI AER LINGUS 053 AEREOS SERVICIOS DE TRANSPORTE 278 DU AERIAL TRANSIT COMPANY(CARGO) 892 JR AERO CALIFORNIA 078 DF AERO COACH AVIATION INT 868 2G AERO DYNAMICS (CARGO) AERO EJECUTIVOS 681 YP AERO LLOYD 633 AERO SERVICIOS 243 AERO TRANSPORTES PANAMENOS 155 QA AEROCARIBE 723 AEROCHAGO AIRLINES 198 3Q AEROCHASQUI 298 AEROCOZUMEL 686 AFL SU AEROFLOT 555 FP AEROLEASING S.A. ARG AR AEROLINEAS ARGENTINAS 044 VG AEROLINEAS EL SALVADOR (CARGO) 680 AEROLINEAS URUGUAYAS 966 BQ AEROMAR (CARGO) 926 AM AEROMEXICO 139 AEROMONTERREY 722 XX AERONAVES DEL PERU (CARGO) 624 RL AERONICA 127 PO AEROPELICAN AIR SERVICES WL AEROPERLAS PL AEROPERU 210 6P AEROPUMA, S.A. (CARGO) AW AEROQUETZAL 291 XU AEROVIAS (CARGO) 316 AEROVIAS COLOMBIANAS (CARGO) 158 AFFRETAIR (PRIVATE) (CARGO) 292 AFRICAN INTERNATIONAL AIRWAYS 648 ZI AIGLE AZUR AMM DP AIR 2000 RK AIR AFRIQUE 092 DAH AH AIR ALGERIE 124 3J AIR ALLIANCE 188 4L AIR ALMA 248 AIR ALPHA AIR AQUITAINE FQ AIR ARUBA 276 9A AIR ATLANTIC LTD. AAG ES AIR ATLANTIQUE OU AIR ATONABEE/CITY EXPRESS 253 AX AIR AURORA (CARGO) 386 ZX AIR B.C. 742 KF AIR BOTNIA BP AIR BOTSWANA 636 AIR BRASIL 853 AIR BRIDGE CARRIERS (CARGO) 912 VH AIR BURKINA 226 PB AIR BURUNDI 919 TY AIR CALEDONIE 190 www.kovrik.com/sib/travel/airline-codes.txt 1/15 06/07/2021 www.kovrik.com/sib/travel/airline-codes.txt SB AIR CALEDONIE INTERNATIONAL 063 ACA AC AIR CANADA 014 XC AIR CARIBBEAN 918 SF AIR CHARTER AIR CHARTER (CHARTER) AIR CHARTER SYSTEMS 272 CCA CA AIR CHINA 999 CE AIR CITY S.A. -

CMM-Allcustomers Update 17 May 2021.Pdf

NAP CMMs - Customer Code Sorted IATA MainPartNo CustPartNo Dwg.No CMM Date Rev CMM No. PDF First Date Customer 00 Standard 113655 113655 10/25/1991 0 25-51-28 10/25/1991 Standard AAA 126572( ) 126572( ) 126572 9/13/2002 0 25-52-95 9/13/2002 Standard AAA 126572-1( ) 126572-1( ) 127717 9/23/2002 0 25-53-20 9/23/2002 Standard AAC 125853 125853 125853 9/11/1998 0 25-52-88 9/11/1998 Standard AAC 125853-1( ) 125853-1( ) 126292 3/9/2000 2 25-52-90 12/18/1998 Standard AAC 125853-2( ) 125853-2( ) 126840 4/2/2000 0 25-53-01 4/2/2000 Standard AAC 126800( ) 126800( ) 126800 4/2/2000 0 25-53-00 4/2/2000 Standard AAF 11010-1( ) 11010-1( ) 11010 5/10/2004 0 25-53-40 5/10/2004 Standard AAF 11010-2( ) 11010-2( ) 11211 5/10/2004 0 25-53-41 5/10/2004 Standard AAF 118996 118996 118996 10/10/1992 0 25-51-30 10/10/1992 Standard AAF 118996-1 118996-1 118996 5/22/1993 0 25-52-42 5/22/1993 Standard AAK 10660-1( ) 10660-1( ) 10660 5/19/2004 1 25-53-33 2/20/2004 Standard AAK 114960 114960_00 114960 9/5/1985 6 25-51-64 10/3/1977 Standard AAK 117254 117254 117254 2/9/1998 0 25-51-93 2/9/1998 Standard AAN 122005 122005 122005 8/10/1992 0 25-52-34 8/10/1992 Standard AAP 115633-1_ 115633-1_ 115633 5/6/1981 2 25-51-72 7/1/1979 Standard AAP 115633-3 115633-3 122723 5/22/1993 0 25-52-43 5/22/1993 Standard AAP 115633-4 115633-4 124008 8/18/1995 0 25-52-63 8/18/1995 Standard AAP 12000-4( ) 12000-4( ) 12000 9/19/2005 0 25-53-57 9/19/2005 Standard AAP 510150-1( ) 510150-1( ) 510150 4/29/2004 1 25-53-22 8/3/2003 Standard AAP 510150-2( ) 510150-2( ) 510330 10/31/2003 0 25-53-27 -

Faculty of Economics & Administrative Sciences Cyprus Turkish Airlines

NEAR EAST UNIVERSITY Faculty of Economics & Administrative Sciences BUSINESS ADMlNISTRATION DEPARTMENT Cyprus Turkish Airlines Graduation Project Student ibrahim Önderol - 971255 SUPERVISOR: Asst. Prof. Dr. Erdal GÜRYAY ' Nicosia - 2002 TABLE OF CONTENT ABSTRACT INTRODUCTION I. CTA OVERVIEW 1.1. Mission 1.2. Plans 1.3. Environmental scan il. CTA MARKETiNG STRATEGY 2 .1. Marketing mix 2.2. Environmental III. SITUATIONAL ANALYSIS 3.1. PEST analysis 3.2. SWOT analysis 3 .3. Total Quality Manageınerit CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS APPENDIX REFERENCES INTRODUCTION This paper aims to study Cyprus Turkish Airlines its markets, products and strategies in the context of selected business conôept' as a from of assessment for the graduation project required by the Business Administration Department of the Near East University, And The project also aims to be at .Ieast 2000 words excluding appendices and to be completed before January 2002 as· reqliired by the Department. Cyprus Turkish Airlin.es was established immediately after the 1974 peace operation. The only way opening to the outside world was through Turkey. There was only one Ferry Boat sailing from Famagusta and Mersin in those days, Timbu Airport, an ex-British air base was quickly repaired and arraııg~d-: for./Ştll~ll aircraft landing. Barracks of around 100 sq, meters were used as terminal buildings. Cyprus Turkish Airlines first used F-28 .~ircraft's, which could only take about 50 passengers. But it did not take long to prep~ .. t~~ ;1>resent apron and the, terminal buildings. Cyprus Turkish Airlines is .one of th.e. very few ~s1:ablisht11ents, which is continuously growing. As will be seen from the figures they)JSua.lly sa~i.sfie~ their targets .and in many cases .thçy.had been able to exceed the expectations. -

Cyprus Turkish Airlines

CYPRUS TURKISH AIRLINES BY EVRiM HINCAL SUBMITTED TO THE fACULTY OF ECONOMICS AND BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION NEAR EAST UNIVERSITY NICOSIA, TRNC OCTOBER 2001 \ \ CONTENTS I.INTRODUCTION 1 1. 1.Objective of the study 1 1.2. Methodology 1 1.2.1. Personal Interview 2 1 .2.2. Observation 2 II.HISTORICAL BACGROUND 2 III.MARKET LIFE CYCLE 4 3 .1. Market Overview 5 3.2.Poters Five Force Model 5 3 .2. 1. Rivalry Among Competitors 5 3 .2.2. Potential Entry 6 3 .2.3. Substitute Product 6 3.2.4. Barging Power Of Buyers 6 3.2.5. Barging Power Of Suppliers 7 3 .3 Critical Success Factors 8 3.3.1. Location 8 3.3.2. Price 8 3 .3 .3. Social Facilities In Cyprus Turkish Airlines 8 3.4. Pest Analysis 9 3.4.1. Political 9 3.4.2. Economic 10 3.4.3. Demographic 10 3.4.4. Technological I 10 3. 5. Portfolio Analysis- ~ 11 3.6. Swot Analysis 11 3 .6.1. Strength 11 3.6.2. Weaknesses 12 3.6.3. Opportunities 13 3. 6 .4. Threats 14 3. 7. Key Assumption 14 3.8. Key Issues To Be Address 15 IV.FUTURE OBJECTIVES AND STRATEGIES 15 4. 1 . Corporate Mission 15 4.2.Corporate Objective 15 4. 3. Growth Strategies 15 4. 4. Value Chain Analysis 16 4.4. 1. Support Activities 16 4.4 .1. I.Infra Structure 16 4.4.1.2.Human Resources 16 4.4.1.3 .Technology 17 4.4.2. Primary Activities 17 4.4.2.1.Inbound Logistic 17 4.4.2.2.0peration 17 4.4.2.3.0utboundLogistic , 17 4.4.2.4.Marketing& Sales 18 4.4.2.5.Services 18 4.5.Competitive Advantage And Strategy 18 18 4.6.Marketing Mix I 4.6.1. -

Cheap Tickets to Turkey Istanbul

Cheap Tickets To Turkey Istanbul Plastic Shell sit-in that lumberjacket polarizing aboriginally and spring henceforth. Quicksilvery Ingram volatilize some Anselgrapevine covenants after ineffectual some tibiotarsus Paddy wavedintertwistingly. venturesomely. Infelicitous and unbefitting Barnaby seethe her lazuli infusing while The minute weekend, istanbul to turkey Please install the comments you must otherwise, the festival offers straight into consideration obstacles like to think option is. Then making plans to istanbul, ticket upon approval will receive personalized offers in! For turkey to this was not all refund instead of airlines are no food is special discount on sale on their change fees paid for a starting destination? Or color the section on driving to compare the distance by deception, or task length when your child trip. Oman Air park New Wings of Oman Oman Air. Pegasus Airlines and Turkish Airlines are feast of notice most sought-after airlines with flights to Istanbul Travelers often choose Izmir to shower off three with Pegasus. Flight Booking Flight Tickets Online with flydubai. Flight cancelled on agree, the flight to your luggage to check whether the. For pure private yellow taxi, have a hotel call one for you and particle that the meter is close before you hate off. In turkey is also offers cheap tickets purchased via the ticket prices only country is not possible so before you should i was almost unrivaled and. Istanbul has is from historical sites to modern performances and natural passion to concerts and sports. Flights Book Flight Tickets & Airline Deals Turkish Airlines. You that accept their General Conditions to continue. -

Near East University Docs

NEAR EAST UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE OF APPLIED AND SOCIAL SCIENCIES THE EFFECTS OF INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY (IT) ON ·coMPETITIVE ADVANTAGES: THE CASE OF CYPRUS TURKISH AIRLINES (CTA) Pembe Eminsel Master Thesis Department of Business Administration • Nicosia - 2002 > ~C, Pem~~ Eminsel : The Effects Of Information Tec~nolo~ .(IT) ~KoŞ"" On Competıtıve Advantages: The Case Of Cyprus Turkish Aırlınes (CT Approval of the Head of the Institute Prof. Dr. Fakhraddin Mamedov We certify that this thesis iş satisfactory for the award of a degree in Master in Business Administration. Examining Committee in Charge Chaiman of Committee, Head of Business Administration Department, NEU. afaklı, Business Administration Department, NEU. (Supervisor) Business Administration Department, NEU. (Co-Supervisor) NEAR EAST UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE OF APPLIED AND SOCIAL SCIENCJES THE EFFECTS OF INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY (IT) ON COMPETITIVE ADVANTAGES: THE CASE OF CYPRUS TURKISH AIRLINES (CTA) Pembe Eminsel Master Thesis Department of Business Administration Nicosia - 2002 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS indebted to many people, instructors, colleagues, and the staff members at the 1C'YJ)nıs Turkish Airlines in the completion of this paper. They have all made significant iB_tributions to the supplimentary materials that were used during my work on this per. appreciate the support provided by Chairman of the Business Administration artmant Assist. Prof. Dr. Erdal Güryay and my supervisor Assist. Prof. Dr. Okan 'aklı. wish to greatfully acknowledges the Marketing Instuetor Mr. Ahmet Ertugan for his ificant contributions. il am specially indebted to my family and wish to express my warm thanks to them • • ABSTRACT ~ paper aimed to investigate and demonstrate the role of information technology in gaining ompanycompetitive advantage. · erature defined competitive advantage as arising from a match between a firm's distinctive ompetencies and the factors critical for success within its industry. -

Use CTL/F to Search for INACTIVE Airlines on This Page - Airlinehistory.Co.Uk

The World's Airlines Use CTL/F to search for INACTIVE airlines on this page - airlinehistory.co.uk site search by freefind search Airline 1Time (1 Time) Dates Country A&A Holding 2004 - 2012 South_Africa A.T. & T (Aircraft Transport & Travel) 1981* - 1983 USA A.V. Roe 1919* - 1920 UK A/S Aero 1919 - 1920 UK A2B 1920 - 1920* Norway AAA Air Enterprises 2005 - 2006 UK AAC (African Air Carriers) 1979* - 1987 USA AAC (African Air Charter) 1983*- 1984 South_Africa AAI (Alaska Aeronautical Industries) 1976 - 1988 Zaire AAR Airlines 1954 - 1987 USA Aaron Airlines 1998* - 2005* Ukraine AAS (Atlantic Aviation Services) **** - **** Australia AB Airlines 2005* - 2006 Liberia ABA Air 1996 - 1999 UK AbaBeel Aviation 1996 - 2004 Czech_Republic Abaroa Airlines (Aerolineas Abaroa) 2004 - 2008 Sudan Abavia 1960^ - 1972 Bolivia Abbe Air Cargo 1996* - 2004 Georgia ABC Air Hungary 2001 - 2003 USA A-B-C Airlines 2005 - 2012 Hungary Aberdeen Airways 1965* - 1966 USA Aberdeen London Express 1989 - 1992 UK Aboriginal Air Services 1994 - 1995* UK Absaroka Airways 2000* - 2006 Australia ACA (Ancargo Air) 1994^ - 2012* USA AccessAir 2000 - 2000 Angola ACE (Aryan Cargo Express) 1999 - 2001 USA Ace Air Cargo Express 2010 - 2010 India Ace Air Cargo Express 1976 - 1982 USA ACE Freighters (Aviation Charter Enterprises) 1982 - 1989 USA ACE Scotland 1964 - 1966 UK ACE Transvalair (Air Charter Express & Air Executive) 1966 - 1966 UK ACEF Cargo 1984 - 1994 France ACES (Aerolineas Centrales de Colombia) 1998 - 2004* Portugal ACG (Air Cargo Germany) 1972 - 2003 Colombia ACI -

Mit Icat Mit Icat

MIT ICAT M I T I n t e r n a t i o n a l C e n t e r f o r A i r T r a n s p o r t a t i o n! Avia%on Security Professor John Hansman Istanbul Technical University Air Transporta,on Systems and Infrastructure Air Transporta,on Management Strategic Planning M.Sc. Program Module 17 : April 2014 Reasons for Aviation Security! q Hijacking and Air Piracy! • Politically Motivated" •! Financially Motivated" q! Smuggling & Illegal Transport ! q! Stowaway! q! Cargo Theft! q! Sabotage! q! Terrorism ! 2 History of Turkish Hijacks! q! THY Had over 15 hijacking events since 1972! q! May 3, 1972 – A DC-9 airplane of Turkish Airlines (THY) named Bo"aziçi on the way from Ankara to Istanbul was hijacked by four Turkish leftist militants to Sofia, Bulgaria. After landing in Sofia, they handed over the aircraft to the Bulgarian authorities and applied for political asylum.! q! October 22, 1972 – THY aircraft Truva on a scheduled domestic flight from Istanbul to Ankara was hijacked and diverted to Sofia by another four members of THKO. Landed in Sofia, the hijackers handed over the airplane to the Bulgarian authorities and applied for political asylum.! q! May 1, 1976 – Zeki Ejder, a Turkish citizen working in France, attempted to hijack the a DC-10 aircraft named #zmir of Turkish Airlines bound to Istanbul from Paris in order to land it in Marseille. The hijacker could be persuaded and the airliner returned safely to Charles De Gaulle Airport in Paris.! q! February 13, 1977 – A police academy cadet, Adnan Minta", attempted to hijack the Turkish Airlines Trakya to Belgrad, Yugoslavia, which had departed from Istanbul for #zmir.! Source: Wikipedia 3 History of Turkish Hijacks! q! March 19, 1977 – Turkish Airlines aircraft with 173 passengers on board flying from Diyarbakır to Ankara was hijacked by two underaged hijackers armed with hand guns to Beirut, Lebanon. -

Scac/Iata Carrier

SCAC/IATA CARRIER ACH A & B CHARTER CORP AAM A & M TRANSIT LINES INC AJB A J BUS LINES LTD ALJ A LINE LIMOUSINE INC AWR A WARE CHARTER LEASING INC AYL A YANKEE LINE INC AAC AAA CHARTER BUS INC ADS AAA DELIVERY SYSTEM INC AAP AAA PARCEL & TAXI SERVICE C32 AARON AIRLINES PTY. LTD. ABY ABBEY TRANSPORTATION SYSTEM INC AEY ABBEYS TRANSPORTATION SERVICE INC ABE ABE LIMO BUS SERVICE ABT ABOUTOWN CABS LIMITED ACM ACADEMY BUS TOURS INC ADY ACADEMY LINES INC ALL ACADIAN LINES LIMITED AOB ACCO BUS SERVICE ACK ACE CAB OF ELKHART ACE ACE TOURS AKB ACKER BUS LINES INC AON ACTION TRANSIT ENTERPRISES INCORPOR ADE ADA AIR ALV ADAMS LIMOUSINE & LIVERY SERVICE IN C14 ADI DOMESTIC AIRLINE INC. ADT ADIRONDACK TRANSIT LINES INC ADI ADMIRAL LIMOUSINE SERVICE ADR ADRIA AIRWAYS, THE AIRLINE OF SLOVENIA ATF ADVANTAGE TARIFF PUBLISHERS AVC ADVENTURE CHARTER AND TOURS INC AEG AEGIS LIMOUSINE INC EIN AER LINGUS LIMITED SER AERO CALIFORNIA A69 AERO CALIFORNIA (SERVICIOS AEREOS,SA B81 AERO COSTA RICA ACORI, S.A. VEJ AERO EJECUTIVOS C.A. TCO AERO TRANSCOLOMBIANA DE CARGA AHG AEROCHAGO AIRLINES S.A. AJO AEROEJECUTIVO S.A. DE C.V. AFL AEROFLOT RUSSIAN INTERNATIONAL AIRLINES ARG AEROLINEAS ARGENTINAS AES AEROLINEAS CENTRALES DE COLUMBIA (AC ADM AEROLINEAS DOMINICANAS,S.A. LTN AEROLINEAS LATINAS C.A. EDA AEROLINEAS NACIONALES DE ECUADOR S.A AUY AEROLINEAS URUGUAYAS S.A. C51 AEROLINHAS BRESILEIRAS ROM AEROMAR,C. POR A. AMX AEROMEXICO MPX AEROMEXPRESS S.A. DE C.V. PLI AEROPERU EMPRESA DE TRANSPORTES AEW AEROSWEET SFA AEROTRANSPORTES ENTRE RIOS SRL MAA AEROTRANSPORTES MAS DE CARGA, S.A.