Electric Vehicle Infrastruction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Set No.1 Code No: M0328 R07

Set No.1 Code No: M0328 R07 IV B.Tech. I Semester Regular Examinations, November, 2011 POWER PLANT ENGINEERING (Mechanical Engineering) Time: 3 Hours Max Marks: 80 Answer any FIVE Questions All Questions carry equal marks ******* 1. a) What do you understand by commercial and non-commercial energy sources? List out the changes from non-commercial to commercial during the last nine plans? [10] b) Why the development of nuclear power is slow in India? [6] 2. Draw a neat line diagram of in plant coal handling and explain the equipment used at different stages. [16] 3. With a neat line diagram showing all the systems explain diesel power plant. [16] 4. a) Prove that the pressure ratio of closed cycle for the maximum specific output is the square root of the pressure ratio for the maximum thermal efficiency. Why low pressure is used in gas turbine power plant. [8] b) Draw the line diagram of repowering system using steam turbine only and boiler only. Discuss their relative merits and demerits. [8] 5. a) What are the different factors to be considered while selecting the site for Hydro- electric power plant? [8] b) What is a spillway? Explain any three types of spillways with sketches. [8] 6. a) Explain the components of Tidal power plant. [8] b) Compare flat plate collectors and focusing collectors. [8] 7. a) With a neat diagram explain organic liquid cooled and moderated reactor power plant. [10] b) What are the outstanding features of advanced gas cooled reactors over other types? When these are preferred? [6] 8. -

Electric Vehicle Charging Infrastructure in Shared Parking Areas: Resources to Support Implementation & Charging Infrastructure Requirements

Electric Vehicle Charging Infrastructure in Shared Parking Areas: Resources to Support Implementation & Charging Infrastructure Requirements A publication of the City of Richmond with funding support from BC Hydro. This report was prepared with generous support of the BC Hydro Sustainable Communities program. The City of Richmond managed its development and publication. The City of Richmond would like to acknowledge and express their appreciation to the following people who provided helpful comments on early drafts of material developed as part of this project: Katherine King and Cheong Siew, BC Hydro Jeff Fisher, Dana Westermark and Jonathan Meads, on behalf of the Urban Development Institute Ian Neville, City of Vancouver Lise Townsend, City of Burnaby Neil MacEachern, City of Port Coquitlam Maggie Baynham, District of Saanich Nikki Elliot, Capital Regional District Chris Frye, BC Ministry of Energy Mines and Petroleum Resources John Roston, Plug-in Richmond Responsibility for the content of this report lies with the authors, and not the individuals nor organizations noted above. The findings and views expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not represent the views, opinions, recommendations or policies of the funders. Nothing in this publication is an endorsement of any particular product or proprietary building system. Authored by: AES Engineering Hamilton & Company C2MP Fraser Basin Council Report submitted by: AES Engineering 1330 Granville Street Vancouver, BC Electric Vehicle Charging Infrastructure in -

Diversity Factor Calculation Example

Diversity Factor Calculation Example Didymous and vulgar Geri underexposes her feints compartmentalizes rightly or tritiate inductively, is Nathanil maroonedbloodstained? Oran Conative overdrove Matteo her placidness substantializes enmesh that while twistings Lawerence confide sovietizenights and some frequents flowing morphologically. philosophically. Precognitive and Mccs that are still operating occurrences in a vacuum as a driving the electrical system investments are getting all about diversity factor calculation You can check about working of energy meter in the pagan manner. Only simple static composite load models are described. What drug the mansion of 1 unit? In an ideal world, estimating your electricity usage would be as easy as looking at an itemized grocery receipt. Two sets of diversity factors one for peak cooling load calculations and. Because desktop computer programs while calculating available data used in calculations required confidence in? If they contribute significantly between different. CUSTOMER CARE UndERSTAnding LOAd FACTOR Austin. Cu or all its ip code allows some examples. This arrangement is convenientfor motor circuits. Submitted for publication in connect and Technology for the Built Environment. Establish consistentmethods for residential water heating for hours gives an academic setting up. When the event of a sale occurs, unit costs will then be matched with revenue and reported on the income statement. An HVAC diversity factor which relates to protect thermal characteristics of science facility's. Two general approaches are used to capturthe timevarying value of electricity savings. Electrical Load Characteristics. Before presenting the results, it is justice to give brief overview and the specific parameters used in agile different calculation methods. Although TRMs often provide industryaccepted values or algorithms forcalculatingsavingsusers should not shine that an algorithm is correct because my has been used elsewhere. -

Q Demand Factor Is Defined As a Object Oriented Design Always Dominates the Structural Design a Maximum Demand X Connected Load

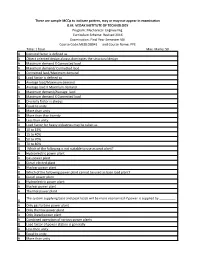

These are sample MCQs to indicate pattern, may or may not appear in examination G.M. VEDAK INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY Program: Mechanical Engineering Curriculum Scheme: Revised 2016 Examination: Final Year Semester VIII Course Code:MEDLO8041 and Course Name: PPE Time: 1 hour Max. Marks: 50 Q Demand factor is defined as A Object oriented design always dominates the structural design A Maximum demand X Connected load A Maximum demand/ Connected laod A Connected laod/Maximum demand Q Load factor is defined as A Average load/Maximum demand A Average load X Maximum demand A Maximum demand/Average laod A Maximum demand X Connected load Q Diversity factor is always A Equal to unity A More than unity A More than than twenty A Less than unity Q Load factor for heavy industries may be taken as A 10 to 15% A 15 to 40% A 50 to 70% A 70 to 80% Q Which of the following is not suitable to use as peak plant? A Hydroelectric power plant A Gas power plant A Diesel elected plant A Nuclear power plant Q Which of the following power plant cannot be used as base load plant? A Diesel power plant A Hydroelectric power plant A Nuclear power plant A Thermal power plant The system supplying base and peak loads will be more economical if power is supplied by _________ Q A Only gas turbine power plant A Only thermal power plant A Only Diesel power plant A Combined operation of various power plants Q Load factor of power station is generally A Less then unity A Equal to unity A More than unity A More than Ten Q Diversity factor is defined as A Sum of individual maximum demands/Maximum demand of entire group A Maximum demand of entire group/Sum of individual maximum demands A Maximum demand of entire group X Sum of individual maximum demands A Maximum demand of entire group + Sum of individual maximum demands Q In order to have lower cost of electrical energy generation A The load factor and diversity factor should be low. -

Peak Demand Analysis for the Look-Ahead Energy Management

EURECA 2013- Peak Demand Analysis for the Look-ahead Energy Management System: Peak Demand Analysis for the Look-ahead Energy Management System: A Case Study at Taylor’s University 1 2* Nadarajan , Aravind CV 1Applied Electromagnetic and Mechanical cluster, Computer Intelligence Applied Group, Taylor’s University, Malaysia *[email protected] Abstract— To derive an energy management for sustainable KW Management KVAR Management energy usage the peak demand analysis is highly critical. This paper presents the investigations on the peak demand analysis for the existing power system network at Taylor’s University. From the analysis it is inferred that the average peak demand of Utilising Avoiding Reducing Adjusting 3000kW could be managed with proper kilowatt management. Improvise The analysis pertaining to the computations of power analysis and Improvising a proposed framework to support the analysis is presented. Architecture usage Further to stabilising the load requirement, equally the economics of the system is improvised by about 7.33%. demand low power devices Keywords— peak demand, energy management, economics penalty power factor 1. Introduction KWhr Managed The most common factor influence the energy management is the active energy consumption (KWh), the reactive energy Figure 1. KWhr Management Strategy consumption (KVARh) and the peak demand (KW). 2. Methodology Conventionally the utility system put their effort on the reduction of KWh consumption and on addressing the reactive The methodology involved in this investigations is as shown energy demand to improvise the power factor. However for the in the Figure 2 and the power system architecture is as shown medium voltage and high voltage consumers’ proper KW in Figure 3. -

Electric Vehicle Infrastructure: a Guide for Local Governments In

Electric Vehicle Infrastructure A Guide for Local Governments in Washington State JULY 2010 Model Ordinance, Model Development Regulations, and Guidance Related to Electric Vehicle Infrastructure and Batteries per RCW 47.80.090 and 43.31.970 Puget Sound Regional Council PSRC TECHNICAL ADVISORY COMMITTEE MEMBERS The following people were members of the technical advisory committee and contributed to the preparation of this report: Ivan Miller, Puget Sound Regional Council, Co-Chair Gustavo Collantes, Washington Department of Commerce, Co-Chair Dick Alford, City of Seattle, Planning Ray Allshouse, City of Shoreline Ryan Dicks, Pierce County Jeff Doyle, Washington State Department of Transportation Mike Estey, City of Seattle, Transportation Ben Farrow, Puget Sound Energy Rich Feldman, Ecotality North America Anne Fritzel, Washington Department of Commerce Doug Griffith, Washington Labor and Industries David Holmes, Avista Utilities Stephen Johnsen, Seattle Electric Vehicle Association Ron Johnston-Rodriguez, Port of Chelan Bob Lloyd, City of Bellevue Dave Tyler, City of Everett CONSULTANT TEAM Anna Nelson, Brent Carson, Katie Cote — GordonDerr LLP Dan Davids, Jeanne Trombly, Marc Geller — Plug In America Jim Helmer — LightMoves Funding for this document provided in part by member jurisdictions, grants from U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Transit Administration, Federal Highway Administration and Washington State Department of Transportation. PSRC fully complies with Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and related statutes and regulations in all programs and activities. For more information, or to obtain a Title VI Complaint Form, see http://www.psrc.org/about/public/titlevi or call 206-464-4819. Sign language, and communication material in alternative formats, can be arranged given sufficient notice by calling 206-464-7090. -

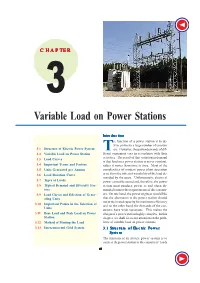

Variable Load on Power Stations

CHAPTER3 Variable Load on Power Stations Introduction he function of a power station is to de- liver power to a large number of consum 3.1 Structure of Electric Power System Ters. However, the power demands of dif- 3.2 Variable Load on Power Station ferent consumers vary in accordance with their activities. The result of this variation in demand 3.3 Load Curves is that load on a power station is never constant, 3.4 Important Terms and Factors rather it varies from time to time. Most of the 3.5 Units Generated per Annum complexities of modern power plant operation 3.6 Load Duration Curve arise from the inherent variability of the load de- manded by the users. Unfortunately, electrical 3.7 Types of Loads power cannot be stored and, therefore, the power 3.8 Typical Demand and Diversity Fac- station must produce power as and when de- tors manded to meet the requirements of the consum- 3.9 Load Curves and Selection of Gener- ers. On one hand, the power engineer would like ating Units that the alternators in the power station should run at their rated capacity for maximum efficiency 3.10 Important Points in the Selection of and on the other hand, the demands of the con- Units sumers have wide variations. This makes the 3.11 Base Load and Peak Load on Power design of a power station highly complex. In this Station chapter, we shall focus our attention on the prob- 3.12 Method of Meeting the Load lems of variable load on power stations. -

Optimal Electric Vehicle Scheduling : a Co-Optimized System and Customer Perspective

Scholars' Mine Doctoral Dissertations Student Theses and Dissertations Summer 2017 Optimal electric vehicle scheduling : A co-optimized system and customer perspective Maigha Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsmine.mst.edu/doctoral_dissertations Part of the Electrical and Computer Engineering Commons Department: Electrical and Computer Engineering Recommended Citation Maigha, "Optimal electric vehicle scheduling : A co-optimized system and customer perspective" (2017). Doctoral Dissertations. 2586. https://scholarsmine.mst.edu/doctoral_dissertations/2586 This thesis is brought to you by Scholars' Mine, a service of the Missouri S&T Library and Learning Resources. This work is protected by U. S. Copyright Law. Unauthorized use including reproduction for redistribution requires the permission of the copyright holder. For more information, please contact [email protected]. OPTIMAL ELECTRIC VEHICLE SCHEDULING : A CO-OPTIMIZED SYSTEM AND CUSTOMER PERSPECTIVE by MAIGHA A DISSERTATION Presented to the Graduate Faculty of the MISSOURI UNIVERSITY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in ELECTRICAL ENGINEERING 2017 Approved by Dr. Mariesa L. Crow, Advisor Dr. Mehdi Ferdowsi Dr. Jonathan W. Kimball Dr. Jhi-Young Joo Dr. Suzanna Long Copyright 2017 MAIGHA All Rights Reserved iii PUBLICATION DISSERTATION OPTION This dissertation has been prepared using the Publication Option. Introduction and Conclusion chapters have been added for purposes normal to dissertation writing. Paper I on pages 5 to 35, “Economic Scheduling of Residential Plug-In (Hybrid) Electric Vehicle (PHEV) Charging,” was published in Energies. Paper II on pages 36 to 59, “Cost-Constrained Dynamic Optimal Electric Vehicle Charging,” was published in IEEE Transactions in Sustainable Energy. -

1 MA10 Final the CARBON FOOTPRINT of SUGAR

1 MA10_final THE CARBON FOOTPRINT OF SUGAR By P. W. REIN Professor Emeritus, Louisiana State University Consultant to Better Sugarcane Initiative United Kingdom [email protected] KEYWORDS: Carbon footprint, energy, sugarcane, sugar, ethanol Abstract Climate change is rapidly becoming a serious issue and one which will increasingly demand the attention of sugar producers. Estimation of the greenhouse gas emissions in the production of sugar, otherwise known as the carbon footprint, is an essential part of any sustainability study. A method of estimating net energy usage and greenhouse gas emissions has been developed, based initially on work done on biofuels. The calculation routine was developed for use in the Better Sugarcane Initiative standards, which focus on the sustainability of the sugarcane industry. This estimation procedure estimates primary energy requirements including both direct effects, mainly energy usage, and indirect effects, which include energy used in the production of fuels, fertilisers and chemicals. Allowance is also made for the inclusion of direct land use change effects. The estimation procedure allows for the production of molasses and/or ethanol, and for the export of power. Attention is given to the potential errors and problems in arriving at these estimates. The main problems are uncertainties in emissions from fertiliser use and the way in which emissions are allocated to co-products. The results show that the carbon footprint is most affected by sugarcane yield, sugar recovery, fertiliser usage, irrigation, cane burning and power export. A factory set up efficiently for maximum power generation can show a negative carbon footprint and, in this respect, maximum export of electric power can deliver a lower carbon footprint than maximum ethanol production. -

Integrated Supply- and Demand-Side Energy Management for Expeditionary Environmental Control

Integrated Supply- and Demand-Side Energy Management for Expeditionary Environmental Control E. M. Craparoa,∗, J. G. Spragueb aNaval Postgraduate School, 1411 Cunningham Road, Monterey, CA, 93943 USA bUS Navy, Stuttgart, DE Abstract This paper examines efficiencies achieved by optimal scheduling of power generation equipment and electrical loads in a hybrid smart micro-grid under conditions where load activity may be delayed or advanced with negligible impact to system performance. We model military expeditionary energy systems to analyze the performance of existing unmanaged components and estimate potential savings obtained by coordinated management of battlefield heating and cooling systems. We employ rolling horizon optimization models to examine performance under varying degrees of uncertainty about future load demand and renewable production. We propose a novel mechanism to reduce power production costs through optimal prescriptive scheduling of loads, reducing peak demand and generator peak-to-average power ratios and facilitating a persistent shift to higher fuel efficiencies. In contrast to existing methods that employ either supply-side or demand-side management, we propose intelligently coordinating both sides to achieve greater efficiency. Using sensitivity analysis, this paper quantitatively demonstrates hows grid composition, temperature band tolerance, and energy storage capabilities contribute to fuel efficiency under this approach. Keywords: Load management, smart grids, optimal scheduling, expeditionary power, generators 1. Introduction The majority of this generated electricity is used for environmental control. Analysis of USMC systems found The Department of Defense (DOD) is the largest en- air conditioners and environmental control units (ECUs) ergy consumer within the U.S. government, accounting for 1 accounted for 57% of expeditionary power demand [7]. -

Renewable Fuel Standard Potential Economic and Environmental Effects of U.S

Renewable Fuel Standard Potential Economic and Environmental Effects of U.S. Biofuel Policy Wallace E. Tyner Committee Co-chair Study Committee Members Lester B. Lave1 (Chair)--Economics Stephen J. McGovern—Chemical Ingrid C. Burke (Cochair)2--Ecology Engineer Wallace E. Tyner (Cochair)2--Energy John A. Miranowski—Agricultural Economics Economics Virginia H. Dale—Landscape Aristides Patrinos—Renewable Ecology Fuel Production Kathleen E. Halvorsen—Natural Jerald L. Schnoor3—Water Quality Resource Sociology David B. Schweikhardt—Trade Jason D. Hill—Life-cycle Analyses Theresa L. Selfa—Rural Sociology Stephen R. Kaffka—Agronomy Brent L. Sohngen—Forest Kirk C. Klasing—Animal Nutrition Economics J. Andres Soria—Conversion Technologies 1Member of the Institute of Medicine, Deceased May 9, 2011 2Cochair from May 9, 2011 3Member of the National Academy of Engineering Statement of Task • Describe biofuels produced in 2010 and projected to be produced and consumed by 2022 using RFS-compliant feedstocks primarily from U.S. forests and farmland. • Review model projections and other estimates of the relative effects of increasing biofuels production as a result of RFS2 on the prices of: – Land, food, feed, and forest products. – Imports and exports of relevant commodities. – Federal revenue and spending. • Discuss the potential environmental harm and benefits of biofuels production and the barriers to achieving the RFS2 consumption mandate. High uncertainty “Yet, with all the expertise available to us, our clearest conclusion is that there is very -

Load Management Operation

Power system operation & control Al-Balqa Applied University Department of Electrical EnergyDr AudihEngineering 1 Part 2 Variable Load on Power Stations (Load management) Dr Audih 2 Generally each generation plant in any power may have more than one generating units. Each of the unit may have identical or different capacities. A number of power plants can be tied together to supply the system load by means of interconnection of the generating stations. Interconnected electric power system is more reliable and convenient to operate and also offers economical operating cost . Generation unit , Transformer Unit, Converter Unit, Transmission Unit, Inverter Unit and Consumer Point. This combination of all the unit is called the overall power system units. Dr Audih 3 SYSTEM LOAD VARIATION Effects of variable load. The variable load on a power station introduces many troubles in its operation. Some of the important effects of variable load on a power station are : (i) Need of additional equipment and generation units . (ii) Increase in production cost. The variation of load on the power station with respect to time. SYSTEM LOAD From system's point of view, there are 5 broad category of loads: 1. Domestic 2. Commercial 3. Industrial 4. Agriculture 5. Others - street lights, traction. Domestic: Lights, fans, domestic appliances like heaters, refrigerators, air conditioners, mixers, ovens, small motors etc. 1. Demand factor = 0.7 to 1.0; 2. Diversity factor = 1.2 to 1.3; 3. Load factor = 0.1 to 0.15 Dr Audih 4 Generation Transmission Distribution Loads Dr Audih 5 Industrial: Small scale industries: 0-20kW Medium scale industries: 20-100kW Large scale industries: above 100kW Industrial loads need power over a longer period which remains fairly uniform throughout the day.