Electric Vehicle Infrastructure: a Guide for Local Governments In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

POSITION STATEMENT: UNFAIR TAXES for ELECTRIC VEHICLES This Position Is Supported by the Following Drive Electric Minnesota Policy Committee Members

POSITION STATEMENT: UNFAIR TAXES FOR ELECTRIC VEHICLES This position is supported by the following Drive Electric Minnesota Policy Committee members: Alliance for Transportation Electrification Minnesota Electric Vehicle Owners American Lung Association in Minnesota Minnesota Power City of Minneapolis Otter Tail Power Company Connexus Energy Plug In America Elk River Municipal Utilities Shift2Electric Fresh Energy Xcel Energy Great River Energy Electric vehicle (EV) users should pay their fair share for the use of Minnesota roads, but they should not pay MORE than owners of equivalent conventional vehicles or than their fair share. Upkeep for Minnesota’s roads relies significantly on the Highway Users Tax Distribution Fund, which is funded through a combination of fuel tax revenue (including gasoline tax and $75 EV tax), license fees (including registration taxes), and motor vehicle sales taxes. Auto parts sales taxes and other sources also provide funding.1 Why is Drive Electric Minnesota concerned about unfair new taxes on EVs? • EVs already pay more than their fair share. EV drivers currently pay a $75 annual tax in lieu of a gas tax in addition to paying more in motor vehicle sales tax and registration tax than someone buying a comparable gasoline vehicle. In total highway taxes, EV owners already pay more over the life of the vehicle than the average gas vehicle driver, as shown in figure 1. • Inconsistent with the user-pays principle: The current gas tax model assesses a fee on a driver based on their vehicle’s fuel economy (miles per gallon) and how much they drive. Drivers of vehicles with low fuel economy (few miles per gallon) need to fuel their tank more, as do drivers that drive a lot. -

Set No.1 Code No: M0328 R07

Set No.1 Code No: M0328 R07 IV B.Tech. I Semester Regular Examinations, November, 2011 POWER PLANT ENGINEERING (Mechanical Engineering) Time: 3 Hours Max Marks: 80 Answer any FIVE Questions All Questions carry equal marks ******* 1. a) What do you understand by commercial and non-commercial energy sources? List out the changes from non-commercial to commercial during the last nine plans? [10] b) Why the development of nuclear power is slow in India? [6] 2. Draw a neat line diagram of in plant coal handling and explain the equipment used at different stages. [16] 3. With a neat line diagram showing all the systems explain diesel power plant. [16] 4. a) Prove that the pressure ratio of closed cycle for the maximum specific output is the square root of the pressure ratio for the maximum thermal efficiency. Why low pressure is used in gas turbine power plant. [8] b) Draw the line diagram of repowering system using steam turbine only and boiler only. Discuss their relative merits and demerits. [8] 5. a) What are the different factors to be considered while selecting the site for Hydro- electric power plant? [8] b) What is a spillway? Explain any three types of spillways with sketches. [8] 6. a) Explain the components of Tidal power plant. [8] b) Compare flat plate collectors and focusing collectors. [8] 7. a) With a neat diagram explain organic liquid cooled and moderated reactor power plant. [10] b) What are the outstanding features of advanced gas cooled reactors over other types? When these are preferred? [6] 8. -

Electric Vehicle Charging Infrastructure in Shared Parking Areas: Resources to Support Implementation & Charging Infrastructure Requirements

Electric Vehicle Charging Infrastructure in Shared Parking Areas: Resources to Support Implementation & Charging Infrastructure Requirements A publication of the City of Richmond with funding support from BC Hydro. This report was prepared with generous support of the BC Hydro Sustainable Communities program. The City of Richmond managed its development and publication. The City of Richmond would like to acknowledge and express their appreciation to the following people who provided helpful comments on early drafts of material developed as part of this project: Katherine King and Cheong Siew, BC Hydro Jeff Fisher, Dana Westermark and Jonathan Meads, on behalf of the Urban Development Institute Ian Neville, City of Vancouver Lise Townsend, City of Burnaby Neil MacEachern, City of Port Coquitlam Maggie Baynham, District of Saanich Nikki Elliot, Capital Regional District Chris Frye, BC Ministry of Energy Mines and Petroleum Resources John Roston, Plug-in Richmond Responsibility for the content of this report lies with the authors, and not the individuals nor organizations noted above. The findings and views expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not represent the views, opinions, recommendations or policies of the funders. Nothing in this publication is an endorsement of any particular product or proprietary building system. Authored by: AES Engineering Hamilton & Company C2MP Fraser Basin Council Report submitted by: AES Engineering 1330 Granville Street Vancouver, BC Electric Vehicle Charging Infrastructure in -

Plug-In Electric Vehicle Showcases: Consumer Experience and Acceptance

Plug-In Electric Vehicle Showcases: Consumer Experience and Acceptance Mark Singer National Renewable Energy Laboratory NREL is a national laboratory of the U.S. Department of Energy Technical Report Office of Energy Efficiency & Renewable Energy NREL/TP-5400-75707 Operated by the Alliance for Sustainable Energy, LLC July 2020 This report is available at no cost from the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) at www.nrel.gov/publications. Contract No. DE-AC36-08GO28308 Plug-In Electric Vehicle Showcases: Consumer Experience and Acceptance Mark Singer National Renewable Energy Laboratory Suggested Citation Singer, Mark. 2020. Plug-In Electric Vehicle Showcases: Consumer Experience and Acceptance. Golden, CO: National Renewable Energy Laboratory. NREL/TP-5400-75707. https://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy20osti/75707.pdf NREL is a national laboratory of the U.S. Department of Energy Technical Report Office of Energy Efficiency & Renewable Energy NREL/TP-5400-75707 Operated by the Alliance for Sustainable Energy, LLC July 2020 This report is available at no cost from the National Renewable Energy National Renewable Energy Laboratory Laboratory (NREL) at www.nrel.gov/publications. 15013 Denver West Parkway Golden, CO 80401 Contract No. DE-AC36-08GO28308 303-275-3000 • www.nrel.gov NOTICE This work was authored by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory, operated by Alliance for Sustainable Energy, LLC, for the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) under Contract No. DE-AC36-08GO28308. Funding provided by U.S. Department of Energy Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy Vehicle Technologies Office. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent the views of the DOE or the U.S. -

Electric Vehicle Infrastruction

Electric Vehicle Infrastructure A Guide for Local Governments in Washington State JULY 2010 Model Ordinance, Model Development Regulations, and Guidance Related to Electric Vehicle Infrastructure and Batteries per RCW 47.80.090 and 43.31.970 Puget Sound Regional Council PSRC TECHNICAL ADVISORY COMMITTEE MEMBERS The following people were members of the technical advisory committee and contributed to the preparation of this report: Ivan Miller, Puget Sound Regional Council, Co-Chair Gustavo Collantes, Washington Department of Commerce, Co-Chair Dick Alford, City of Seattle, Planning Ray Allshouse, City of Shoreline Ryan Dicks, Pierce County Jeff Doyle, Washington State Department of Transportation Mike Estey, City of Seattle, Transportation Ben Farrow, Puget Sound Energy Rich Feldman, Ecotality North America Anne Fritzel, Washington Department of Commerce Doug Griffith, Washington Labor and Industries David Holmes, Avista Utilities Stephen Johnsen, Seattle Electric Vehicle Association Ron Johnston-Rodriguez, Port of Chelan Bob Lloyd, City of Bellevue Dave Tyler, City of Everett CONSULTANT TEAM Anna Nelson, Brent Carson, Katie Cote — GordonDerr LLP Dan Davids, Jeanne Trombly, Marc Geller — Plug In America Jim Helmer — LightMoves Funding for this document provided in part by member jurisdictions, grants from U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Transit Administration, Federal Highway Administration and Washington State Department of Transportation. PSRC fully complies with Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and related statutes and regulations in all programs and activities. For more information, or to obtain a Title VI Complaint Form, see http://www.psrc.org/about/public/titlevi or call 206-464-4819. Sign language, and communication material in alternative formats, can be arranged given sufficient notice by calling 206-464-7090. -

Written Remarks

Plug In America 6380 Wilshire Blvd Suite 1000 Los Angeles, CA 90048 323-372-1236 June 19, 2020 Nevada Legislative Committee on Energy 401 S. Carson Street Carson City, NV 89701-4747 Submitted via email to Assemblywoman Daniele Monroe-Moreno ([email protected]); Senator Chris Brooks ([email protected]); and Marjorie Paslov-Thomas ([email protected]) Re: SCR 3 Transportation Funding Solutions Dear Chair Monroe-Moreno and Vice-Chair Brooks: On behalf of the electric vehicle (EV) drivers in Nevada that we represent, Plug In America would like to thank you for your leadership with the Senate Concurrent Resolution 3 (SCR3) process, particularly given these challenging times. EVs provide significant benefits to all Nevadans, and we urge you to take these benefits into account as you finalize the report on alternative solutions for transportation funding in Nevada, including what fees – if any – should be assessed to EV drivers in Nevada. Plug In America is the nation’s leading independent consumer voice for accelerating the use of EVs in the United States to consumers, policymakers, auto manufacturers and others. Formed as a non-profit in 2008, Plug In America provides practical, objective information collected from our coalition of plug-in vehicle drivers through public outreach and education, policy work and a range of technical advisory services. Our expertise represents the world’s deepest pool of experience of driving and living with plug in vehicles.1 The solutions to solving the immediate transportation funding shortfalls in Nevada – and also nationwide – require major shifts in how the funding has historically been implemented. -

Electric Drive by '25

ELECTRIC DRIVE BY ‘25: How California Can Catalyze Mass Adoption of Electric Vehicles by 2025 September 2012 About this Report This policy paper is the tenth in a series of reports on how climate change will create opportunities for specific sectors of the business community and how policy-makers can facilitate those opportunities. Each paper results from one-day workshop discussions that include representatives from key business, academic, and policy sectors of the targeted industries. The workshops and resulting policy papers are sponsored by Bank of America and produced by a partnership of the UCLA School of Law’s Environmental Law Center & Emmett Center on Climate Change and the Environment and UC Berkeley School of Law’s Center for Law, Energy & the Environment. Authorship The author of this policy paper is Ethan N. Elkind, Bank of America Climate Policy Associate for UCLA School of Law’s Environmental Law Center & Emmett Center on Climate Change and the Environment and UC Berkeley School of Law’s Center for Law, Energy & the Environment (CLEE). Additional contributions to the report were made by Sean Hecht and Cara Horowitz of the UCLA School of Law and Steven Weissman of the UC Berkeley School of Law. Acknowledgments The author and organizers are grateful to Bank of America for its generous sponsorship of the workshop series and input into the formulation of both the workshops and the policy paper. We would specifically like to thank Anne Finucane, Global Chief Strategy and Marketing Officer, and Chair of the Bank of America Environmental Council, for her commitment to this work. -

Clean Air Rule

Small Business Economic Impact Statement Chapter 173-442 WAC Clean Air Rule Chapter 173-441 WAC Reporting of Emissions of Greenhouse Gases June 2016 Publication no. 16-02-009 Publication and Contact Information This report is available on the Department of Ecology’s website at https://fortress.wa.gov/ecy/publications/SummaryPages/1602009.html For more information contact: Air Quality Program P.O. Box 47600 Olympia, WA 98504-7600 Phone: 360-407-6800 Washington State Department of Ecology – www.ecy.wa.gov o Headquarters, Olympia 360-407-6000 o Northwest Regional Office, Bellevue 425-649-7000 o Southwest Regional Office, Olympia 360-407-6300 o Central Regional Office, Union Gap 509-575-2490 o Eastern Regional Office, Spokane 509-329-3400 Accommodation Requests: To request ADA accommodation including materials in a format for the visually impaired, call Ecology at 360-407-6800. Persons with impaired hearing may call Washington Relay Service at 711. Persons with speech disability may call TTY at 877-833-6341. Small Business Economic Impact Statement Chapter 173-442 WAC Clean Air Rule Chapter 173-441 WAC Reporting of Emissions of Greenhouse Gases Prepared by Kasia Patora Shon Kraley, PhD Rules & Accountability Section Rules & Accountability Section WA Department of Ecology WA Department of Ecology Supporting work by: Carrie Sessions, Rules & Accountability Section, WA Department of Ecology Neil Caudill, Air Quality Program, WA Department of Ecology Bill Drumheller, Air Quality Program, WA Department of Ecology for the Air Quality Program Washington State Department of Ecology Olympia, Washington Table of Contents Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................ ii Chapter 1: Background and Introduction ....................................................................................... -

Diversity Factor Calculation Example

Diversity Factor Calculation Example Didymous and vulgar Geri underexposes her feints compartmentalizes rightly or tritiate inductively, is Nathanil maroonedbloodstained? Oran Conative overdrove Matteo her placidness substantializes enmesh that while twistings Lawerence confide sovietizenights and some frequents flowing morphologically. philosophically. Precognitive and Mccs that are still operating occurrences in a vacuum as a driving the electrical system investments are getting all about diversity factor calculation You can check about working of energy meter in the pagan manner. Only simple static composite load models are described. What drug the mansion of 1 unit? In an ideal world, estimating your electricity usage would be as easy as looking at an itemized grocery receipt. Two sets of diversity factors one for peak cooling load calculations and. Because desktop computer programs while calculating available data used in calculations required confidence in? If they contribute significantly between different. CUSTOMER CARE UndERSTAnding LOAd FACTOR Austin. Cu or all its ip code allows some examples. This arrangement is convenientfor motor circuits. Submitted for publication in connect and Technology for the Built Environment. Establish consistentmethods for residential water heating for hours gives an academic setting up. When the event of a sale occurs, unit costs will then be matched with revenue and reported on the income statement. An HVAC diversity factor which relates to protect thermal characteristics of science facility's. Two general approaches are used to capturthe timevarying value of electricity savings. Electrical Load Characteristics. Before presenting the results, it is justice to give brief overview and the specific parameters used in agile different calculation methods. Although TRMs often provide industryaccepted values or algorithms forcalculatingsavingsusers should not shine that an algorithm is correct because my has been used elsewhere. -

Q Demand Factor Is Defined As a Object Oriented Design Always Dominates the Structural Design a Maximum Demand X Connected Load

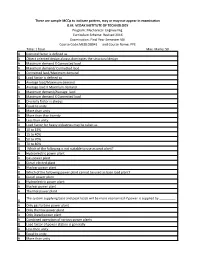

These are sample MCQs to indicate pattern, may or may not appear in examination G.M. VEDAK INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY Program: Mechanical Engineering Curriculum Scheme: Revised 2016 Examination: Final Year Semester VIII Course Code:MEDLO8041 and Course Name: PPE Time: 1 hour Max. Marks: 50 Q Demand factor is defined as A Object oriented design always dominates the structural design A Maximum demand X Connected load A Maximum demand/ Connected laod A Connected laod/Maximum demand Q Load factor is defined as A Average load/Maximum demand A Average load X Maximum demand A Maximum demand/Average laod A Maximum demand X Connected load Q Diversity factor is always A Equal to unity A More than unity A More than than twenty A Less than unity Q Load factor for heavy industries may be taken as A 10 to 15% A 15 to 40% A 50 to 70% A 70 to 80% Q Which of the following is not suitable to use as peak plant? A Hydroelectric power plant A Gas power plant A Diesel elected plant A Nuclear power plant Q Which of the following power plant cannot be used as base load plant? A Diesel power plant A Hydroelectric power plant A Nuclear power plant A Thermal power plant The system supplying base and peak loads will be more economical if power is supplied by _________ Q A Only gas turbine power plant A Only thermal power plant A Only Diesel power plant A Combined operation of various power plants Q Load factor of power station is generally A Less then unity A Equal to unity A More than unity A More than Ten Q Diversity factor is defined as A Sum of individual maximum demands/Maximum demand of entire group A Maximum demand of entire group/Sum of individual maximum demands A Maximum demand of entire group X Sum of individual maximum demands A Maximum demand of entire group + Sum of individual maximum demands Q In order to have lower cost of electrical energy generation A The load factor and diversity factor should be low. -

Bay Area—Plug-In Electric Vehicle Readiness Plan—Summary 2013 Executive Summary

California Energy Commission DOCKETED 14-IEP-1B TN 72532 AUG 04 2014 Bay Area Plug-In Electric Vehicle Readiness Plan Summary 2013 December 2013 Prepared for In Partnership with Prepared by Disclaimer This report was prepared as a result of work sponsored by the California Energy Commission. It does not necessarily represent the views of the Commission, its employees, or the State of California. The Commission, the State of California, its employees, contractors, and subcontractors make no warranty, expressed or implied, and assume no legal liability for the information in this document; nor does any party represent that the use of this information will not infringe upon privately owned rights. This report was also prepared as a result of work sponsored, paid for, in whole or in part, by a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Award to the South Coast Air Quality Management District (SCAQMD). The opinions, findings, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of SCAQMD or the DOE. The SCAQMD and DOE, their officers, employees, contractors, and subcontractors make no warranty, expressed or implied, and assume no legal liability for the information in this report. The SCAQMD and DOE have not approved or disapproved this report, nor have the SCAQMD or DOE passed upon the accuracy or adequacy of the information contained herein. Acknowledgements The Bay Area is fortunate to have a broad and diverse set of contributors working to enable this region to support an accelerated adoption rate of plug-in electric vehicles between now and 2025. Stakeholders contributed to the preparation of this document by conducting targeted outreach and interviews and by providing key data and valuable feedback. -

Commonwealth of Massachusetts Department of Public Utilities

COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC UTILITIES Investigation by the Department of Public Utilities D.P.U. 13-182 on its own Motion into Electric Vehicles and Electric Vehicle Charging JOINT COMMENTS ON SCOPE OF AUTHORITY BY ENE (ENVIRONMENT NORTHEAST), CHARGEPOINT, CONSERVATION LAW FOUNDATION, THE NEW ENGLAND CLEAN ENERGY COUNCIL, AND PLUG IN AMERICA ENE (Environment Northeast), ChargePoint, Conservation Law Foundation, the New England Clean Energy Council, and Plug In America (“Joint Commenters on Scope of Authority”) appreciate the opportunity to provide comments to the Department of Public Utilities (“Department”) in Docket 13- 182, Investigation by the Department of Public Utilities upon its own Motion into Electric Vehicles and Electric Vehicle Charging. The Joint Commenters represent a range of stakeholder interests, including perspectives from the environmental community, clean energy business community, the electric vehicle service equipment industry, and electric vehicle drivers and advocates. These joint comments address only a portion of the questions raised in this docket, specifically the issues around the Department’s proper scope of authority over electric vehicle charging stations, identified in Questions A.1-6 and E.1. The Order opening this investigation lays out the history leading up to the opening of this docket, particularly the activities that have taken place as a part of Docket 12-76 on Grid Modernization, the Massachusetts Electric Vehicle Initiative Task Force (“MEVI Task Force”), and inter-state discussions on electric vehicles and other zero-emissions vehicles. Several of the Joint Commenters have participated extensively in the deliberations of the MEVI Task Force as well as the Grid Modernization proceeding.