The Rule of Law Conflict Between Poland and the EU in the Light of Two Integration Discourses: Neofunctionalism and Intergovernmentalism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EU Urban Agenda at the Urban Forum “Cities

April 2014 - 13th issue NEWSLETTERhttp://urban-intergroup.eu ear partners, dear colleagues, this 13th newsletter of the URBAN “DIntergroup is the last one of this term. I was very pleased to chair the UR- BAN Intergroup over the last five years. I think that we should be proud of what we have achieved together during this half a decade. All along this term, we welcomed in our Intergroup MEPs from most of EU Mem- ber States, all political groups and almost all committees. We also got support from new partners – culminating at 83 – from local, regional, national and European level that represent the interests of Europe’s town and cities or work in the domain relevant for urban development.” Jan Olbrycht President of the URBAN Intergroup ver the past five years, we organised no less than 27 conferences and over 30 “Omeetings, concerning issues such as transports, housing, biodiversity, culture, sustainable development or urban planning. Members of the URBAN Intergroup fol- lowed closely what was happening in their respective committees in the European Parliament. They reported on latest developments and defended urban related issues in various fields. Moreover, our members and partners were deeply involved in the negotiations of the EU post 2013 cohesion policy, especially concerning the urban ele- ments in the structural funds’ regulations. Finally, we are very proud to have initiated two preparatory actions: “RURBAN”, which aimed at improving urban-rural partner- ships, and “World cities: EU-third countries cooperation on urban development”, cur- rently still under preparation. We also followed closely the symbolic change of name of the Directorate-General for Regional Policy (DG REGIO) and welcomed the addition of “Urban Policy”. -

European Parliament Elections 2019 - Forecast

Briefing May 2019 European Parliament Elections 2019 - Forecast Austria – 18 MEPs Staff lead: Nick Dornheim PARTIES (EP group) Freedom Party of Austria The Greens – The Green Austrian People’s Party (ÖVP) (EPP) Social Democratic Party of Austria NEOS – The New (FPÖ) (Salvini’s Alliance) – Alternative (Greens/EFA) – 6 seats (SPÖ) (S&D) - 5 seats Austria (ALDE) 1 seat 5 seats 1 seat 1. Othmar Karas* Andreas Schieder Harald Vilimsky* Werner Kogler Claudia Gamon 2. Karoline Edtstadler Evelyn Regner* Georg Mayer* Sarah Wiener Karin Feldinger 3. Angelika Winzig Günther Sidl Petra Steger Monika Vana* Stefan Windberger 4. Simone Schmiedtbauer Bettina Vollath Roman Haider Thomas Waitz* Stefan Zotti 5. Lukas Mandl* Hannes Heide Vesna Schuster Olga Voglauer Nini Tsiklauri 6. Wolfram Pirchner Julia Elisabeth Herr Elisabeth Dieringer-Granza Thomas Schobesberger Johannes Margreiter 7. Christian Sagartz Christian Alexander Dax Josef Graf Teresa Reiter 8. Barbara Thaler Stefanie Mösl Maximilian Kurz Isak Schneider 9. Christian Zoll Luca Peter Marco Kaiser Andrea Kerbleder Peter Berry 10. Claudia Wolf-Schöffmann Theresa Muigg Karin Berger Julia Reichenhauser NB 1: Only the parties reaching the 4% electoral threshold are mentioned in the table. Likely to be elected Unlikely to be elected or *: Incumbent Member of the NB 2: 18 seats are allocated to Austria, same as in the previous election. and/or take seat to take seat, if elected European Parliament ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• www.eurocommerce.eu Belgium – 21 MEPs Staff lead: Stefania Moise PARTIES (EP group) DUTCH SPEAKING CONSITUENCY FRENCH SPEAKING CONSITUENCY GERMAN SPEAKING CONSTITUENCY 1. Geert Bourgeois 1. Paul Magnette 1. Pascal Arimont* 2. Assita Kanko 2. Maria Arena* 2. -

10.4.2019 A8-0029/114 Amendment 114 Róża Gräfin Von Thun Und Hohenstein, Olga Sehnalová, Dita Charanzová, Kateřina Konečn

10.4.2019 A8-0029/114 Amendment 114 Róża Gräfin von Thun und Hohenstein, Olga Sehnalová, Dita Charanzová, Kateřina Konečná, Biljana Borzan, Julia Reda, Julia Pitera, Tadeusz Zwiefka, Janusz Lewandowski, Dariusz Rosati, Jan Olbrycht, Elżbieta Katarzyna Łukacijewska, Danuta Maria Hübner, Bogusław Sonik, Danuta Jazłowiecka, Jarosław Kalinowski, Michał Boni, Antanas Guoga, Petras Auštrevičius, Agnieszka Kozłowska-Rajewicz, Adam Szejnfeld, Marek Plura, Barbara Kudrycka, Dubravka Šuica, Ivana Maletić, Željana Zovko, Marijana Petir, Krzysztof Hetman, Jerzy Buzek, Emil Radev, Lidia Joanna Geringer de Oedenberg, Janusz Zemke, Krystyna Łybacka, Adam Gierek, Bogdan Andrzej Zdrojewski, Eduard Kukan, Laima Liucija Andrikienė, Michaela Šojdrová, Tomáš Zdechovský, Renate Weber, Robert Rochefort, Momchil Nekov, Sergei Stanishev, Georgi Pirinski, Emilian Pavel, Peter Kouroumbashev, Maria Grapini, Ioan Mircea Paşcu, Daciana Octavia Sârbu, Wajid Khan, Luigi Morgano, Maria Noichl, Davor Škrlec, Ruža Tomašić, Jozo Radoš, Tonino Picula, Ivo Vajgl, Tanja Fajon, Miriam Dalli, Pavel Poc, Jan Keller, Monika Beňová, Boris Zala, Miltiadis Kyrkos, Martina Dlabajová, Miroslav Poche, Igor Šoltes, Petr Ježek, Filiz Hyusmenova, Monika Smolková, Vladimír Maňka, Jiří Maštálka, Jaromír Kohlíček, Stefan Eck, Luke Ming Flanagan, Gabriele Zimmer, Marie-Pierre Vieu, Miguel Viegas, João Pimenta Lopes, João Ferreira, Anja Hazekamp, Martin Schirdewan, Paloma López Bermejo, Cornelia Ernst, Takis Hadjigeorgiou, Helmut Scholz, Marina Albiol Guzmán, Mihai Ţurcanu, Jiří Pospíšil, Stanislav -

Ms Mairead Mcguinness European Commissioner for Financial Services, Financial Stability and the Capital Markets Union Mr

TO: Ms Mairead McGuinness European Commissioner for Financial Services, Financial Stability and the Capital Markets Union Mr Valdis Dombrovskis European Commission Executive Vice-President for An Economy that Works for People CC: Mr Frans Timmermans European Commission Executive Vice-President for the European Green Deal Ms Kadri Simson European Commissioner for Energy Brussels, 13 April 2021 Dear Executive Vice-President Dombrovskis, Dear Commissioner McGuinness, We are convinced that the Taxonomy Regulation is crucial for the European Union to achieve both the new greenhouse gas emissions reduction target for 2030 and climate neutrality by 2050. Additionally, the Regulation should help strengthening the European Union’s strategic resilience and global economic competitiveness, maintaining its energy security and affordability, boosting growth and job creation and supporting a just and inclusive energy transition that leaves nobody behind. However, to what extent the Taxonomy Regulation will ultimately meet these expectations depends primarily on the technical screening criteria (TSC) defined in the Delegated Act on climate change mitigation and adaptation. We understand the European Commission will publish it later this month, whereupon the European Parliament may make full use of its scrutinizing prerogatives under Article 290 TFEU. In advance of its publication, we would like to share with you some of our major concerns regarding the revised draft version of this delegated act. Firstly, it is indispensable that the Taxonomy Regulation takes into account transition at the energy system level and supports the most cost-efficient decarbonisation pathway for each Member State in line with the principle of technology neutrality. In this context, it is key to acknowledge the role of gaseous fuels. -

Intercultural & Religious Dialogue

INTERCULTURAL & RELIGIOUS DIALOGUE ACTIVITY REPORT 2018 INTERCULTURAL & RELIGIOUS DIALOGUE Activity Report 2018 INTERCULTURAL & RELIGIOUS DIALOGUE ACTIVITY REPORT 2018 3 INTERCULTURAL & RELIGIOUS DIALOGUE INTERCULTURAL & RELIGIOUS DIALOGUE Activity Report 2018 Activity Report 2018 INTRODUCTION TABLE OF CONTENT DATE ACTIVITY PAGE The EPP Group Intercultural and Religious Dialogue activities aim to promote mutual understanding and an active sense of European citizenship for a peaceful living together. Decision makers are called 6 February Working Group Meeting 7 to provide answers to the complex crisis with political, economic, religious and cultural implications on Initiatives of religious organisations to face climate change in Europe. with CEC 'Intercultural and Religious Dialogue’ does not mean theological discussions in the European 28 February Conference on Oriental Christians in MASHREQ Region: 9 Consequences of the conflicts in the Middle-East on the Parliament. It is about listening to people from the sphere of religion and exchanging views with Christians Communities and future perspectives representatives of academia, governments, European Institutions on issues of common interest or concern and in connection to religion and intercultural relations. 6 March Seminar on the Importance for Europe to Protect Christian 13 Cultural Heritage - Views from the Orthodox Churches The Working Group on 'Intercultural and Religious Dialogue' is an official structure of the EPP 13 March Working Group Meeting 16 Group and is co-chaired by Jan -

European Parliament 2014-2019

European Parliament 2014-2019 Committee on Budgets 2017/0351(COD) 20.6.2018 OPINION of the Committee on Budgets for the Committee on Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs on the proposal for a regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on establishing a framework for interoperability between EU information systems (borders and visa) and amending Council Decision 2004/512/EC, Regulation (EC) No 767/2008, Council Decision 2008/633/JHA, Regulation (EU) 2016/399 and Regulation (EU) 2017/2226 (COM(2017)0793 – C8-0002/2018 – 2017/0351(COD)) Rapporteur for opinion: Bernd Kölmel AD\1156513EN.docx PE616.791v02-00 EN United in diversity EN PA_Legam PE616.791v02-00 2/9 AD\1156513EN.docx EN SHORT JUSTIFICATION The rapporteur welcomes the two Commission proposals for a regulation for establishing a framework for interoperability between EU information systems adopted on 12 December 2017. Both proposals aim at overcoming structural shortcomings in the present EU information management architecture by making information systems interoperable, i.e. able to exchange data and share information. The rapporteur fully subscribes to their purpose, which is to ensure fast access to information, including by law enforcement authorities, to detect multiple identities and combat identity fraud, to facilitate identity checks of third- country nationals and to facilitate the prevention, investigation or prosecution of serious crime and terrorism. The present opinion concerns the proposal on borders and visa, which aims to regulate access to the Visa Information System, the Schengen Information System as currently regulated by Regulation (EC) No 1987/2006, the Entry-Exit System (EES) and the European Travel information and Authorisation System (ETIAS). -

BTI 2012 | Poland Country Report

BTI 2012 | Poland Country Report Status Index 1-10 9.05 # 6 of 128 Political Transformation 1-10 9.20 # 8 of 128 Economic Transformation 1-10 8.89 # 6 of 128 Management Index 1-10 6.79 # 13 of 128 scale: 1 (lowest) to 10 (highest) score rank trend This report is part of the Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Transformation Index (BTI) 2012. The BTI is a global assessment of transition processes in which the state of democracy and market economy as well as the quality of political management in 128 transformation and developing countries are evaluated. More on the BTI at http://www.bti-project.org Please cite as follows: Bertelsmann Stiftung, BTI 2012 — Poland Country Report. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2012. © 2012 Bertelsmann Stiftung, Gütersloh BTI 2012 | Poland 2 Key Indicators Population mn. 38.2 HDI 0.813 GDP p.c. $ 19783 Pop. growth1 % p.a. 0.1 HDI rank of 187 39 Gini Index 34.2 Life expectancy years 76 UN Education Index 0.822 Poverty3 % <2 Urban population % 61.2 Gender inequality2 0.164 Aid per capita $ - Sources: The World Bank, World Development Indicators 2011 | UNDP, Human Development Report 2011. Footnotes: (1) Average annual growth rate. (2) Gender Inequality Index (GII). (3) Percentage of population living on less than $2 a day. Executive Summary The 2009 – 2011 period was marked by several major features. The government is composed of a two-party coalition created after the 2007 parliamentary election. It consists of Civic Platform (PO) and Polish People’s Party (PSL), the latter clearly being the junior partner in the coalition. -

Family in Contemporary Europe

[...] There is a prevailing consensus that the modern family in Europe is entrenched in a serious crisis that is the result of a va- Family in riety of factors, including economic, cultural and social factors whe- re for some time now a wave of cultural revolt has spread, begin- ning with the youth revolution that took place in 1968 and claimed Contemporary Europe the necessity of being free from any “burdens” including moral principles, in order to become people who cannot be stopped by The Role of the Catholic Church anyone in realising their full and unbridled freedom. Without negating the fundamental value of the modern family, in the European Integration Process experts on the matter turn our attention to its threats. They are foremost derived from the belief that the traditional family, espe- cially one that recognises the indissolubility of marriage, is not This publication contains the transcripts only a relic of the past, but above all it is the primary enemy of mo- from speeches and discussions during the conference dern interpersonal communities that are based on the principles in Krakow on 13-14 September 2013 of full freedom. [...] Bp Prof. Tadeusz Pieronek 82.1-,-.8- =,28->>? A-@>0/- AAABC2>802;D-+,2<4B2,5B<; Family in Contemporary Europe 1+.6> =4,/E =4,;043-./ ( The Pontifical University The Robert Schuman The Konrad Adenauer ’Wokó³ nas’ The Group of John Paul II Foundation Foundation Publishing House of the European People's Party Gliwice 2014 &'()(*)+,&*-),*)+ ’Wokó³ nas’ Publishing -

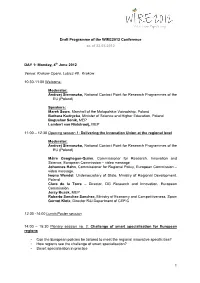

WIRE Draft Programme 23 05 12Www

Draft Programme of the WIRE2012 Conference as of 23.05.2012 DAY 1: Monday, 4 th June 2012 Venue: Krakow Opera, Lubicz 48, Krakow 10:30-11:00 Welcome: Moderator: Andrzej Siemaszko, National Contact Point for Research Programmes of the EU (Poland) Speakers: Marek Sowa , Marshall of the Malopolskie Voivodship, Poland Barbara Kudrycka , Minister of Science and Higher Education, Poland Bogusław Sonik, MEP Lambert van Nistelrooij, MEP 11:00 – 12:30 Opening session 1: Delivering the Innovation Union at the regional level Moderator: Andrzej Siemaszko, National Contact Point for Research Programmes of the EU (Poland) Máire Geoghegan-Quinn , Commissioner for Research, Innovation and Science, European Commission – video message Johannes Hahn , Commissioner for Regional Policy, European Commission – video message, Iwona Wendel , Undersecretary of State, Ministry of Regional Development, Poland Clara de la Torre – Director, DG Research and Innovation, European Commission Jerzy Buzek, MEP Roberto Sanchez Sanchez, Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness, Spain Gernot Klotz , Director R&I Department of CEFIC 12:30 -14:00 Lunch/Poster session 14:00 – 15:30 Plenary session no. 2: Challenge of smart specialisation for European regions • Can the European policies be tailored to meet the regional innovative specificities? • How regions see the challenge of smart specialisation? • Smart specialisation in practice 1 Moderator: Clara de la Torre – Director, DG Research and Innovation, European Commission Rapporteur : Colombe Warin - DG Research and Innovation, European Commission Speakers: Lambert van Nistelrooij , MEP, Rapporteur to General Regulation Ales Gnamus, DG JRC, European Commission Christina Diegelmann, Assembly of European Regions Philippe Vanrie, European Business & Innovation Centre (BICs) Network Sarka Hermanova, Czech Technology Platform 15:30 - 16:00 Coffee Break 16:00 – 17:30 Parallel sessions Parallel session no. -

6516/17 FFF/Mn 1 DRI at the Above Mentioned Part-Session, The

Council of the European Union Brussels, 10 April 2017 (OR. en) 6516/17 PE-RE 4 'I' ITEM NOTE From: General Secretariat of the Council To: Permanent Representatives Committee (part 2) / Council Subject: RESOLUTIONS and DECISIONS adopted by the European Parliament at its part-session in Strasbourg from 3 to 6 April 2017. At the above mentioned part-session, the European Parliament adopted 34 acts1 as follows: - 17 legislative acts - 17 non-legislative acts I. Legislative Acts A. Ordinary Legislative Procedure First reading 1) Characteristics for fishing vessels Report: Werner Kuhn (A8-0376/2016) European Parliament legislative resolution P8_TA(2017)0096 2) Certain aspects of company law Report: Tadeusz Zwiefka (A8-0088/2017) European Parliament legislative resolution P8_TA(2017)0103 3) Money market funds Report: Neena Gill (A8-0041/2015) European Parliament legislative resolution P8_TA(2017)0109 1 To consult the acts, Ctrl + click on the hyperlink (P8 reference) contained in the text concerned. You will be directed to the act as published on the European Parliament's website. 6516/17 FFF/mn 1 DRI EN 4) Prospectus to be published when securities are offered to the public or admitted to trading Report: Petr Ježek (A8-0238/2016) European Parliament legislative resolution P8_TA(2017)0110 5) Wholesale roaming markets Report: Miapetra Kumpula-Natri (A8-0372/2016) European Parliament legislative resolution P8_TA(2017)0128 6) Third countries whose nationals are subject to or exempt from a visa requirement: Ukraine Report: Mariya Gabriel (A8-0274/2016) European Parliament legislative resolution P8_TA(2017)0129 Second reading 7) Medical devices Recommendation for second reading: Glenis Willmott (A8-0068/2017) European Parliament legislative resolution P8_TA(2017)0107 8) In vitro diagnostic medical devices Recommendation for second reading: Peter Liese (A8-0069/2017) European Parliament legislative resolution P8_TA(2017)0108 B. -

To: President of the European Parliament, MEP David Maria Sassoli CC

To: President of the European Parliament, MEP David Maria Sassoli CC: Chair of the European People’s Party Group, MEP Manfed Weber MEPs Siegfried Muresan, Esther De Lange, Jan Olbrycht, José Manuel Fernandes President of the Socialists & Democrats group, MEP Iratxe Garcia MEPs Simona Bonafè, Eric Andrieu, Biljana Borzan, Margarida Marques President of Renew Europe Group, MEP Dacian Ciolos MEPs Valérie Hayer, Luis Garicano Co-Presidents of the Green, European Free AllianceGreens/EFA, MEP Ska Keller, MEP Philippe Lamberts MEPs Ernest Urtasun, Rasmus Andresen Co-Chair of the European Conservatives and Reformists group, MEP Ryszard Legutko Co-Chair of the European Conservatives and Reformists group, MEP Raffaele Fitto President of the Confederal Group of the European United Left/Nordic Green Left GUE/NGL, MEP Manon Aubry President of the Confederal Group of the European United Left/Nordic Green Left GUE/NGL, MEP Martin Schirdewan MEPs Dimitrios Papadimoulis, José Gusmao Vice President of the European Parliament, MEP Mairead Mcguinness Co-Chairs of the Intergroup on Children’s Rights MEP Hilde Vautmans, MEP Saskia Bricmont, MEP Caterina Chinnici, MEP David Lega Chair of the Employment Committee, MEP Lucia Duris Nicholsonova Rapporteur of the ESF+ MEP David Casa Shadow Rapporteur of the ESF+ MEP Brando Benifei Shadow Rapporteur of the ESF+ MEP Monica Semedo Shadow Rapporteur of the ESF+ MEP Simona Baldassarre Shadow Rapporteur of the ESF+ MEP Terry Reintke Shadow Rapporteur of the ESF+ MEP Elzbieta Rafalska Shadow Rapporteur of the ESF+ MEP Jose Gusmao Wednesday 22 July, 2020 Prioritisation of child poverty reduction in the European Parliament’s Resolution on the Recovery Package and the 2021-2027 EU MFF Dear President Sassoli, Dear Members of European Parliament, We are writing to you on behalf of the EU Alliance for Investing in Childreni to ask for your support in ensuring there is adequate EU budget allocation to the fight against child poverty. -

Official Directory of the European Union

ISSN 1831-6271 Regularly updated electronic version FY-WW-12-001-EN-C in 23 languages whoiswho.europa.eu EUROPEAN UNION EUROPEAN UNION Online services offered by the Publications Office eur-lex.europa.eu • EU law bookshop.europa.eu • EU publications OFFICIAL DIRECTORY ted.europa.eu • Public procurement 2012 cordis.europa.eu • Research and development EN OF THE EUROPEAN UNION BELGIQUE/BELGIË • БЪЛГАРИЯ • ČESKÁ REPUBLIKA • DANMARK • DEUTSCHLAND • EESTI • ΕΛΛΑΔΑ • ESPAÑA • FRANCE • ÉIRE/IRELAND • ITALIA • ΚΥΠΡΟΣ/KIBRIS • LATVIJA • LIETUVA • LUXEMBOURG • MAGYARORSZÁG • MALTA • NEDERLAND • ÖSTERREICH • POLSKA • PORTUGAL • ROMÂNIA • SLOVENIJA • SLOVENSKO • SUOMI/FINLAND • SVERIGE • UNITED KINGDOM • BELGIQUE/BELGIË • БЪЛГАРИЯ • ČESKÁ REPUBLIKA • DANMARK • DEUTSCHLAND • EESTI • ΕΛΛΑ∆Α • ESPAÑA • FRANCE • ÉIRE/IRELAND • ITALIA • ΚΥΠΡΟΣ/KIBRIS • LATVIJA • LIETUVA • LUXEMBOURG • MAGYARORSZÁG • MALTA • NEDERLAND • ÖSTERREICH • POLSKA • PORTUGAL • ROMÂNIA • SLOVENIJA • SLOVENSKO • SUOMI/FINLAND • SVERIGE • UNITED KINGDOM • BELGIQUE/BELGIË • БЪЛГАРИЯ • ČESKÁ REPUBLIKA • DANMARK • DEUTSCHLAND • EESTI • ΕΛΛΑΔΑ • ESPAÑA • FRANCE • ÉIRE/IRELAND • ITALIA • ΚΥΠΡΟΣ/KIBRIS • LATVIJA • LIETUVA • LUXEMBOURG • MAGYARORSZÁG • MALTA • NEDERLAND • ÖSTERREICH • POLSKA • PORTUGAL • ROMÂNIA • SLOVENIJA • SLOVENSKO • SUOMI/FINLAND • SVERIGE • UNITED KINGDOM • BELGIQUE/BELGIË • БЪЛГАРИЯ • ČESKÁ REPUBLIKA • DANMARK • DEUTSCHLAND • EESTI • ΕΛΛΑΔΑ • ESPAÑA • FRANCE • ÉIRE/IRELAND • ITALIA • ΚΥΠΡΟΣ/KIBRIS • LATVIJA • LIETUVA • LUXEMBOURG • MAGYARORSZÁG • MALTA • NEDERLAND