Against Normality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Ballad of John & Yoko

THE BALLAD OF JOHN & YOKO Written by Luken Tonjes SincerelyLuken.com ACT 1 1 EXT. NEW YORK CITY. MUSEUM OF MODERN ART. AFTERNOON 1 We see a 1966 JOHN LENNON. He is wearing an English cap, signature sunglasses, and a scarf. JOHN is standing outside of the Museum of modern art, the sound of the city bombards him, the head liner is “YOKO ONO” he is curious so he walks in. R INT. MUSEUM OF MODERN ART. AFTERNOON. It is now quiet. He takes off his cap and sunglasses and proceeds down the hall. There is a picture of YOKO as he is walking in. JOHN sees a ladder in the middle of the room with a magnifying glass hanging from the ceiling, and a canvas attached to the wall. He decides to climb it, he picks up the magnifying glass and takes a look at the canvas. It reads “yes” JOHN is in awe and takes a look to his right, there stands YOKO ONO. She is talking to someone and is laughing. JOHN gives a faint smile. CUT TO: INT. NEW YORK CITY. MUSEUM OF MODERN ART. AFTERNOON.- LATER It is towards the end of the show, there are men taking down some of the pieces. YOKO is directing them and she has a clipboards in her hand. JOHN walks up to YOKO in confidence and taps her on the shoulder. She turns quickly. JOHN Hi, I just wanted to introduce myself, I loved the show. Especially the one piece- YOKO And you are? JOHN is shot down JOHN Sorry? 2. -

THE LOST LENNON TAPES Megatree Liners Index

THE LOST LENNON TAPES MEGATREE INDEX Compiled from the liner note information on the Lost Lennon Tapes MegaTree. Unless otherwise noted, songs are performed by John Lennon. _____________________________________________________________ #9 Dream (alternate mix) .......................................................................................128 #9 Dream (composing demo) ................................................................................203 #9 Dream (demo 2) ..................................................................................................081 #9 Dream (demo) .....................................................................................................063 #9 Dream (LP version) ...........................................................................................063 #9 Dream (partial) ...................................................................................................081 #9 Dream (rough mix) ...................................................................................081, 203 #9 Dream......................................................000, 006, 050, 052, 138, 164, 176, 185 12-Bar Original – The Beatles................................................................................081 1968 marijuana bust.................................................................................................015 1980 Demos...............................................................................................................213 1980.............................................................................................................................200 -

'Peace and Love': Tributes to John Lennon Mark 40Th Anniversary of His Death by Daniel Uria

'Peace and love': Tributes to John Lennon mark 40th anniversary of his death By Daniel Uria Flowers and petals decorate the "Imagine" mosaic at Strawberry Fields in New York City's Central Park on Monday, which is dedicated to late Beatle John Lennon on the eve of the 40th anniversary of his assassination on December 8, 1980. Photo by John Angelillo/UPI |License Photo Dec. 8 (UPI) --For millions of people around the world, it's a moment they will always remember -- where they were, what they were doing and how they felt about it -- when they heard the news that music superstar and former Beatle John Lennon had been gunned down outside his New York City home 40 years ago Tuesday. The date, Dec. 8, 1980, was a momentous one in the history of music and the annals of crime. Now, four decades later, Lennon's murder and his life are the subject of much focus. Julian Lennon, John's first son with wife Cynthia, acknowledged Tuesday's anniversary by posting a photo of his father and the words, "As Time Goes By..." Son Sean Lennon, who was just 5 and inside their home at the Dakota at the time of the shooting, simply posted a photo of himself and his father and mother, singer Yoko Ono. RELATED The Beatles' 'Yellow Submarine' coming to YouTube for streaming event "We all had to say goodbye to John peace and love John," former Beatles drummer and musician Ringo Starr said in a tweet Tuesday, with a photo of him and Lennon. -

BWTB July 30Th 2016

1 Playlist July 31st, 2016 2 9AM The Beatles - All I’ve Got to Do – With The Beatles (Lennon-McCartney) Lead vocal: John Written entirely by John Lennon and introduced to the other Beatles at the session at which it was recorded, The Beatles never played the song again. Lennon has said this soulful ballad was his attempt at making a Smokey Robinson song. Recorded on September 11, 1963 in 14 takes with an overdub (presumably George’s introductory guitar chord) becoming “take 15” and the finished version. “All I’ve Got to Do” marked a rare instance in which John’s lead vocal was not double-tracked. On U.S. album: Meet The Beatles! - Capitol LP The Beatles - Money (That’s What I Want) – With The Beatles (Bradford-Gordy) Lead vocal: John Originally recorded by Barrett Strong and released as a single on Motown’s Tamla and Anna labels in 1959 and 1960 respectively, peaking at #23 in 1960. It was a part of The Beatles’ live repertoire from 1960 to 1964. On July 18, 1963, the group, with George Martin on piano, performed the song live in the studio -- vocals and all -- for six full takes, the final take being deemed the best. Although The Beatles involvement with the 3 recorded track lasted this one day, George Martin continued to add overdubs and tinker with his piano part until the song was completed to his satisfaction on September 30, 1963. On U.S. album: The Beatles’ Second Album - Capitol LP The Beatles - I Should Have Known Better - A Hard Day’s Night (Lennon-McCartney) Lead vocal: John Following their triumphant visit to America The Beatles were thrust back to work. -

A Sweeter Music Preben Antonsen (B.1991) Dar Al-Harb: House of War * Polansky (B’Midbar) No

Cal Performances Presents Program Sunday, January 25, 2009, 3pm The Residents drum no fife (Why We Need War) * Hertz Hall Polansky (B’midbar) No. 6 * A Sweeter Music Preben Antonsen (b.1991) Dar al-Harb: House of War * Polansky (B’midbar) No. 14 * Sarah Cahill, piano Mamoru Fujieda (b.1952) The Olive Branch Speaks John Sanborn, video Terry Riley (b.1935) Be Kind to One Another (Rag) * Commissioned by Stephen B. Hahn and Mary Jane Beddow. PROGRAM * World Premiere Peter Garland (b.1952) After the Wars (excerpts) * Sarah Cahill would like to thank the following individuals: 1. “The nation is ruined, but mountains and Dorothy Cahill, Robert Cole, Miranda Sanborn, Liz and Greg Lutz, Robert Bielecki, rivers remain” (Tu Fu) Margaret Dorfman, Steve Hahn and Mary Jane Beddow, Jerry Kuderna, Paul Dresher, 2. “Summer grass/all that remains/ Joshua Raoul Brody, Skip Sweeney, Bonnie Hughes, Dave Jones Design, Margaret Cromwell, of young warriors’ dreams” (Basho) Joseph Copley and, most of all, John Sanborn, the collaborator and partner of my dreams. Larry Polansky (b.1953) (B’midbar) No. 1 * Cal Performances’ 2008–2009 season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. Frederic Rzewski (b.1938) Peace Dances * Commissioned by Robert Bielecki. Polansky (B’midbar) No. 17 * Education & Community Event Yoko Ono (b.1933) Toning * Composers Forum: The Music of Peace: Can Music Be Political? Friday, January 23, 2009, 6–7:30pm Jerome Kitzke (b.1955) There Is a Field * Wheeler Auditorium 1. I Sarah Cahill and several of the commissioned composers discuss the intersection 2. Look Down Fair Moon of politics and music, especially in works without text, and what it means to write 3. -

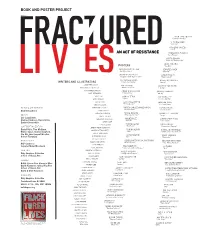

Book and Poster Project an Act of Resistance

BOOK AND POSTER PROJECT IGOR LANGSHTEYN “Secret Formulas” SEYOUNG PARK “Hard Hat” CAROLINA CAICEDO “Shell” AN ACT OF RESISTANCE FRANCESCA TODISCO “Up in Flames” CURTIS BROWN “Not in my Fracking City” WOW JUN CHOI POSTERS “Cracking” SAM VAN DEN TILLAAR JENNIFER CHEN “Fracktured Lives” “Dripping” ANDREW CASTRUCCI LINA FORSETH “Diagram: Rude Algae of Time” “Water Faucet” ALEXANDRA ROJAS NICHOLAS PRINCIPE WRITERS AND ILLUSTRATORS “Protect Your Mother” “Money” SARAH FERGUSON HYE OK ROW ANDREW CASTRUCCI ANN-SARGENT WOOSTER “Water Life Blood” “F-Bomb” KATHARINE DAWSON ANDREW CASTRUCCI MICHAEL HAFFELY MIKE BERNHARD “Empire State” “Liberty” YOKO ONO CAMILO TENSI JUN YOUNG LEE SEAN LENNON “Pipes” “No Fracking Way” AKIRA OHISO IGOR LANGSHTEYN MORGAN SOBEL “7 Deadly Sins” CRAIG STEVENS “Scull and Bones” EDITOR & ART DIRECTOR MARIANNE SOISALO KAREN CANALES MALDONADO JAYPON CHUNG “Bottled Water” Andrew Castrucci TONY PINOTTI “Life Fracktured” CARLO MCCORMICK MARIO NEGRINI GABRIELLE LARRORY DESIGN “This Land is Ours” “Drops” CAROL FRENCH Igor Langshteyn, TERESA WINCHESTER ANDREW LEE CHRISTOPHER FOXX Andrew Castrucci, Daniel Velle, “Drill Bit” “The Thinker” Daniel Giovanniello GERRI KANE TOM MCGLYNN TOM MCGLYNN KHI JOHNSON CONTRIBUTING EDITORS “Red Earth” “Government Warning” JEREMY WEIR ALDERSON Daniel Velle, Tom McGlynn, SANDRA STEINGRABER TOM MCGLYNN DANIEL GIOVANNIELLO Walter Sipser, Dennis Crawford, “Mob” “Make Sure to Put One On” ANTON VAN DALEN Jim Wu, Ann-Sargent Wooster, SOFIA NEGRINI ALEXANDRA ROJAS DAVID SANDLIN Robert Flemming “No” “Frackicide” -

Ono's Lawsuit

SHUKAT ARROW HAFER WEBER & HERBSMAN, LLP Dorothy M. Weber, Esq. (DMW 4734) 494 Eighth Avenue, Suite 600 New York, NY 10001 (212) 245-4580 [email protected] Attorneys for Plaintiff UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK ---------------------------------------------------------------------X YOKO ONO LENNON, Plaintiff, Case No. 1:20-cv-08176 -against- COMPLAINT FREDERIC SEAMAN, Defendant. ---------------------------------------------------------------------X Plaintiff Yoko Ono Lennon, by her attorneys Shukat Arrow Hafer Weber & Herbsman, LLP, alleges for her complaint, upon knowledge and belief as to her own acts and upon information and belief as to the acts of all others, as follows: THE PARTIES, JURISDICTION AND VENUE 1. Plaintiff Yoko Ono Lennon (“Plaintiff” or “Mrs. Lennon”) is a Japanese citizen and resident of the State of New York. She is an internationally known philanthropist, musician and artist. Mrs. Lennon is also the widow of the late John Lennon - one of the most successful and influential musicians of all time. 2. Together, she and Lennon recorded numerous albums, including Unfinished Music No. 1: Two Virgins, Unfinished Music No. 2: Life With the Lions, The Wedding Album, Sometime in New York City, Double Fantasy, which won a Grammy Award in 1981 as Album of the Year, and Milk and Honey, which was released after Lennon’s death. 3. Since the “Bed-Ins for Peace” held in Montreal and Amsterdam in 1969, Mrs. Lennon has dedicated her life to campaigning for world peace and human rights. On September 21, 2020, The Peace Studio inaugurated the “Yoko Ono Imagine Peace Award”. 4. Mrs. Lennon has succeeded to all copyrights interests owned by Lennon prior to his death. -

Festival Program 11Days 40Frames 20

festival program 11days 40frames 20. oslo INTERNASJONALE FILMFESTIVAL 18.↗28. NOVEMBER 2010 FILM/FILMS SPILLEFILMER/FEATURE FILMS A Crowd of Three Japan 10 Behind Blue Skies Sweden 9 Biutiful Spain, Mexico 5 Cold Fish Japan 19 Curling Canada 5 Due Date USA 6 Essential Killing Poland, Norway, Ireland, Hungary 6 Fair Game USA, United Arab Emirates 8 Get Low USA, Germany, Poland 8 Go Get Some Rosemary USA, France 8 HAHAHA Korea, South 9 Ja, vi elsker Norway 9 Kaboom USA, France 10 Last Night USA, France 12 Life During Wartime USA 12 Memory Lane France 13 NY Export: Opus Jazz USA 13 Of Gods and Men France 6 Parade Japan 14 Putty Hill USA 16 Rare Exports: A Christmas Tale Finland, Norway, France, Sweden 16 VELKOMMEN TIL DEN Redline Japan 5 Rubber France 16 20. OSLO INTERNASJONALE FILMFESTIVAL Somewhere USA 3 The Little Tailor France 14 The Myth of the American Sleepover USA 17 Klar for jubileumsfeiring, men festen skal Dans? Fokus på filmer med og om den The Sleeping Beauty France 10 The Strange Case of Angelica Portugal, Spain, France, Brazil 14 mest markeres med fantastiske filmer; legendariske koreografen Pina Bausch, som The Town USA 17 vår festivalmeny bugner av lekre godbiter. døde i fjor sommer. New York City Ballet bidrar The Tree France, Australia 18 Tilva Ros Serbia 18 til en ny tolkning av verk av Jerome Robbins. Tiny Furniture USA 18 Syv år etter at vi avsluttet festivalen med Tuesday, After Christmas Romania 13 We Are What We Are Mexico 17 Sofia Coppolas Lost In Translation har vi Nye sterke debutanter er alltid vår spesialitet. -

Yoko Ono Has Had to Battle to Be Taken Seriously As a Musician

Though long respected in the art world, Yoko Ono has had to battle to be taken seriously as a musician. Her latest release, Between My Head And The Sky, is at last winning the 76 year old the kind of acclaim many would say is overdue. It’s taken a lifetime, literally, but the world is finally ready for Yoko Ono. by Sarah Illingworth Photography by Charlotte Muhal and Sean Lennon © Yoko Ono 2009 A spotlight locks onto the tiny, black-clad artist inhibitions and she’s completely unselfconscious of working with Yoko - if a little stressed out. as she scuttles onstage and opens her sold out onstage. There’s only about 20 people that I’ve “She said, ‘I want to go into the studio show at the Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM, ever seen, really, who are at her level of personal tomorrow.’ And it was one o’clock in the New York) with an a cappella piece. The audience freedom onstage. She just comes alive. As soon as afternoon. She’s like, ‘get me a studio, and get me is immediately transfixed. We’re there to see she walks out there she just enters this zone that’s musicians.’ I had no band for her, I had nothing Yoko’s latest album, Between My Head And The an alternate sort of realm, where she’s completely planned, and we were mixing the EP in three Sky, brought to life - not only by her and the transported by what she’s doing.” days. So it was this really last minute, panicked newest incarnation of the Plastic Ono Band - but It’s a freedom that is also clear when listening thing.” by members of the original ensemble, as well as to Between…, which Sean produced, arranged and The two recordings that came out of that the likes of Paul Simon, Bette Midler, the Scissor has released through Chimera. -

COME TOGETHER Und SWEET TORONTO

InfoMail Nr. 983: JOHN LENNON DVDs COME TOGETHER und SWEET TORONTO Hallo M.B.M., hallo BEATLES-Fan, folgende DVDs (zwei Erstausgaben, eine Neuauflage) bieten wir derzeit an: Herbst 2002 oder 28. Januar 2003: DVD SWEET TORONTO. Direct Video DVD SV 3003 D, England. 12,50 € ERSTAUFLAGE: Aspect: 4:3; Region Code: PAL - Zone 2; Color Mode: Farbe; Sprache: Englisch; Audio: Dolby Digital English 2.0 Stereo; Laufzeit: ca. 56 Minuten. Teil 1, Titel 1: SEPTEMBER 1988: LONDON, ENGLAND: John Lennon Art Exhibits Opens. (3:32). Teil 2, Titel 2-20: SAMSTAG, 13. SEPTEMBER 1969: VARSITY STADIUM, TORONTO, CANADA: Teil 2, Titel 2-6: Bo Diddley: Bo Diddley. Jerry Lee Lewis: Hound Dog. Chuck Berry: Johnny B. Goode. Little Richard: Lucille. JOHN LENNON & THE PLASTIC ONO BAND (YOKO ONO & ERIC CLAPTON & KLAUS VOORMANN & ALAN WHITE): Teil 2, Titel 7-9: Blue Suede Shoes (Carl Perkins). Teil 2, Titel 10-11: Money (That’s What I Want) (Berry Gordy/Janie Bradford). Teil 2, Titel 12-13: Dizzy Miss Lizzie (Larry Williams). Teil 2, Titel 14-15: Yer Blues. Teil 2, Titel 16: Cold Turkey (John Lennon). Teil 2, Titel 17: Give Peace A Chance. YOKO ONO & THE PLASTIC ONO BAND (JOHN LENNON & ERIC CLAPTON & KLAUS VOORMANN & ALAN WHITE): Teil 2, Titel 18: Don’t Worry Kyoto (Mummy’s Only Looking For Her Hand In The Snow) (Yoko Ono). Teil 2, Titel 19: John John (Let’s Hope For Peace) (Ono). Teil 2, Titel 20: Abspann. Gesamtzeit: ca. 56 Minuten. Special Features: An interview with YOKO ONO conducted in London in 1988 at the JOHN LENNON EXHIBITION. -

IMAGINE PEACE: Featuring John & Yoko’S Year of Peace IMAGINE PEACE: Featuring John & Yoko’S Year of Peace

Home » Arts & Features » IMAGINE PEACE: Featuring John & Yoko’s Year of Peace IMAGINE PEACE: Featuring John & Yoko’s Year of Peace September 8, 2011 | Arts & Features, featured, Multimedia, Photos | 0 comments By: Talia Martirano Since the start of her career in 1950 and throughout her partnership with John Lennon in the 60s, Yoko Ono used her artwork to spread a message of peace, which she continues to do till this day. Her message is now being spread to universities across the country, and the Staller Center’s art gallery at Stony Brook is the first venue in New York to hold the exhibition. Rhonda Cooper, the gallery director, says she has been trying to get this exhibit here for a while, and finally some connections made it possible. “The message of this exhibition is about peace, which I think is very timely right now and important for young people,” Cooper said. The show is open to students and the public alike, and will be at the Staller Center until October 15. Along with 198 people, reporters from both Newsday and the New York Times came to see the gallery on September 6, the gallery’s opening night. The exhibition focuses on the themes of peace and love that can bring viewers back to the 1960s, when the marriage of John Lennon and Yoko Ono grabbed a lot of media attention. Always trying to spread the peace, Lennon and Ono used their fame to protest the Vietnam War, even inviting the press in their bedroom to see them at peace. This iconic time is showcased at Staller Center by photos, videos, posters and music from both artists, as a couple and individually. -

Lennon/Mccartney

Pepperdine Law Review Volume 34 Issue 1 Article 5 12-15-2006 I Am the Walrus. - No. I Am!: Can Paul McCartney Transpose the Ubiquitous "Lennon/McCartney" Songwriting Credit to Read "McCartney/Lennon?" An Exploration of the Surviving Beatle's Attempt to Re-Write Music Lore, as it Pertains to the Bundle of Intellectual Property Rights Ezra D. Landes Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/plr Part of the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Ezra D. Landes I Am the Walrus. - No. I Am!: Can Paul McCartney Transpose the Ubiquitous "Lennon/ McCartney" Songwriting Credit to Read "McCartney/Lennon?" An Exploration of the Surviving Beatle's Attempt to Re-Write Music Lore, as it Pertains to the Bundle of Intellectual Property Rights, 34 Pepp. L. Rev. Iss. 1 (2007) Available at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/plr/vol34/iss1/5 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Caruso School of Law at Pepperdine Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pepperdine Law Review by an authorized editor of Pepperdine Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. I Am the Walrus., - No. I Am!: Can Paul McCartney Transpose the Ubiquitous "Lennon/McCartney" Songwriting Credit to Read "McCartney/Lennon?" An Exploration of the Surviving Beatle's Attempt to Re-Write Music Lore, as it Pertains to the Bundle of Intellectual Property Rights 1. See THE BEATLES, 1 Am the Walrus, on MAGICAL MYSTERY TOUR (Capitol Records 1987) (1967). Some of the history behind this song foreshadows the acrimonious songwriting credits dispute that is the focus of this Comment.