Report on Austria's Digital Services

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Letter in PDF Format the Foundation on And

Having problems in reading this e-mail? Click here Tuesday 11th September 2018 issue 815 The Letter in PDF format The Foundation on and The foundation application available on Appstore and Google Play European Union-Russia: after three lost decades, are we moving towards new cohabitation? Author: Pierre Mirel To date relations between the European Union and Russia have been based on the Partnership and Cooperation Agreement (PCA) signed in 1994 and entering into force in 1997 after ratification by the Member States and European Parliament. It established a political framework similar to the association agreements with the countries of Central Europe except that it did not include the establishment of an area of free-trade. Concluded for a period of ten years and renewed automatically yearly the PCA has been suspend for the main part. Has the time not come to think of relations with Russia differently? and on which terms? Read more Elections : Sweden Commission : Japan - Food/School Council : Budget - Economy/Finance - Travel/ETIAS - Eurogroup Parliament : European elections Diplomacy : Serbia/Kosovo Court of Auditors : Erasmus+ Germany : Brexit Austria : Ukraine Spain : Sweden - Euro zone France : Benelux - Franco-German Italy : Justice Lithuania : Poland Czech Republic : Germany Romania : Spain UK : EU- UK Macedonia : Future Council of Europe : Cyprus - Ukraine Eurostat : Growth Culture : Heritage/Days - Congress/Metz - Exhibition/Rotterdam - Art/Paris - Dance/Sevilla - Festival/Vienna Agenda | Other issues | Contact Elections : Sweden: right and left running neck and neck and the populist breakthrough not as big as forecast After the release of the first results in the Swedish general election on 9th September the blocks on the left and right are running neck and neck: 144 MPs for the left and 143 for the right. -

Report for Austria– Questionnaire Related the Administration Control

ADMINISTRATIVE JUSTICE IN EUROPE – Report for Austria– Questionnaire related the administration control list and typology in the 25 Member States of the European Union Preliminary. 1. Administration jurisdictional control was one typical concern of the liberal streams in the 19th century. In Austria, “the Reichsgericht”, a precursor of the Constitutional Court, was created by the December 1867 constitution which also planned creation of a Supreme Administrative Court (hereafter “the Verwaltungsgerichtshof”). However, this project was only fulfilled in 1876. Following this, the Verwaltungsgerichtshof played a decisive role in developing the legal protection system in Austria, establishing fundamental principles for administrative procedural law. Between 1934 and 1938, the Constitutional Court and the Verwaltungsgerichtshof merged to become “the Bundesgerichtshof”. Several judges were retired for political reasons. The introductions of Chambers with extended composition and of actions for administrative failure to act were significant reforms. After 1938, “the Bundesgerichtshof” lost its authority as Constitutional Court as well as several of its administrative jurisdiction authorities. Several judges were retired for political reasons. In 1940 “the Bundesgerichtshof” became “the Verwaltungsgerichtshof in Vienna” which was an administrative authority of the Reich. In 1941, the Verwaltungsgerichtshof became the “Vienna Außensenat” of the “Reichsverwaltungsgericht” by forming an organisational association with other German administrative courts. A few weeks after the Austrian declaration of independence in 1945, Chancellor Renner commissioned Mr. Coreth to revive the Verwaltungsgerichtshof which took up its duties again on 7th December 1945. The legal text on the Verwaltungsgerichtshof was amended and reissued several times but, in substance, it is still in force today. In 1945, the Constitutional Court was re-established with the same capacities as 1933 and it began carrying out its duties again in 1946. -

The Government of the Hungarian People's Republic

CONVENTION BETWEEN THE GOVERNMENT OF THE HUNGARIAN PEOPLE'S REPUBLIC AND THE GOVERNMENT OF THE ITALIAN REPUBLIC FOR THE AVOIDANCE OF DOUBLE TAXATION WITH RESPECT TO TAXES ON INCOME AND CAPITAL AND THE PREVENTION OF FISCAL EVASION.1 The Government of the Hungarian People's Republic and the Government of the Italian Republic, desiring to promote and facilitate the economic relations between the two countries, have agreed to conclude a Convention for the avoidance of double taxation with respect to taxes on income and capital and the prevention of fiscal evasion of which the provisions are the following: Article 1 - Personal scope This Convention shall apply to persons who are residents of one or both of the Contracting States. Article 2 - Taxes covered 1. This Convention shall apply to taxes on income and on capital imposed on behalf of each Contracting State or its political or administrative subdivisions or local authorities, irrespective of the manner in which they are levied. 2. There shall be regarded as taxes on income and on capital taxes imposed on total income, on total capital, or on elements of income or of capital, including taxes on gains from the alienation of movable or immovable property, taxes on the total amounts of wages or salaries paid by enterprises, as well as taxes on capital appreciation. 3. The existing taxes to which this Convention shall apply are the following: (a) in the case of the Italian Republic: (1) the individual income tax (imposta sul reddito delle persone fisiche); (2) the tax on the income of legal entities (imposta sul reddito delle persone giuridiche); and (3) the local income tax (imposta locale sui redditi), even if withheld at the source (hereinafter referred to as "Italian tax"); (b) in the case of the Hungarian People's Republic: (1) the income taxes (j”vedelemad¢k); (2) the profit taxes (nyeres‚gad¢k); (3) the enterprises' special tax (v llalati kl”nad¢); (4) the tax on buildings (h zad¢); 1 Date of Conclusion: 16 May 1977. -

The Empire in the Provinces: the Case of Carinthia

religions Article The Empire in the Provinces: The Case of Carinthia Helmut Konrad Institut für Geschichte, Karl-Franzens-Universität Graz, Attemsgasse 8/II, [505] 8010 Graz, Austria; [email protected] Academic Editors: Malachi Hacohen and Peter Iver Kaufman Received: 16 May 2016; Accepted: 1 August 2016; Published: 5 August 2016 Abstract: This article examines the legacy of the Habsburg Monarchy in the First Austrian Republic, both in the capital, Vienna, and in the province of Carinthia. It concludes that Social Democracy, often cited as one of the six ingredients that held the old Empire together, took on distinct forms in the Republic’s different federal states. The scholarly literature on the post-1918 “heritage” of the Monarchy therefore needs to move beyond monolithic generalizations and toward regionally focused comparative studies. Keywords: empire; socialism; Jews; Habsburg Monarchy; Austria; Vienna; Carinthia; German Nationalism; Sprachenkampf 1. Introduction Which forms did the ideas take that allowed the Habsburg monarchy to persist, despite the diversity of nationalisms present in the small Republic of German-Austria, for so long after the end of the First World War? What was the “glue” that held this multiethnic empire together, when its collapse had been predicted since 1848, and which of its elements continued to exist beyond 1918? How was this heritage expressed in the different regions of the new republic? At least six factors can be identified as ingredients of the “glue” that held the monarchy together: first, the Emperor, a figure who symbolized the fusion of the complex linguistic, ethnic and religious components of the Habsburg state; second, the administrative officials, who were loyal to the Emperor and worked in the ubiquitous and even architecturally similar buildings of the Monarchy’s district authorities and train stations; third, the army, whose members promoted the imperial ideals through their long terms of service and acknowledged linguistic diversity. -

Open Letter Chancellor Kurz

Federal Chancellor Sebastian Kurz Federal Chancellery Ballhausplatz 2 1010 Vienna Austria 27 September 2018 Sebastian Kurz, your leadership is needed to protect the youth As the former President of the World Federation of Public Health Associations, I had the privileGe to visit many countries which stronGly reduced their smokinG rate and effectively protect their non-smokers. Austria was not yet able to do so. Now, I also have the Good fortune of havinG a younG man from Austria livinG in my home as part of a Student Exchange Scheme. I am concerned for his health and the health of his siblinGs, his friends and his fellow Austrians. That’s why I would like to share some of our experiences from Australia. Smoking in Austria and Australia The followinG OECD data show the ‘daily smokinG rates’ in our countries. Since the 1970s, there are sliGhtly more smokers in Austria but two-thirds less smokers in Australia: Source: https://data.oecd.orG/healthrisk/daily-smokers.htm This marked contrast is also seen in youth smokers. In Austria, 27% of 15 year olds were smokers in 2013. In Australia, younG people are now overwhelminGly rejectinG all forms of smokinG. In 2014 the percentaGe of i secondary students aGed 15 years who smoked tobacco was less than 5% . The latest statistics indicate that this has reduced even further, so that in 2016 less than 1% of 12-15 year olds had ever tried smokinGii. What could Austria learn from Australia? There are several lessons that can be learnt from the persistent approach taken by Australian governments. -

With Kurz and Rutte, Merkel Won Allies in Reshaping the EU by Maurizio Ferrera and Alexander Damiano Ricci

With Kurz and Rutte, Merkel won allies in reshaping the EU By Maurizio Ferrera and Alexander Damiano Ricci After the electoral successes of Emmanuel Macron in France and Angela Merkel in Germany, two new political events defined the contours of the new political playground in Europe. On the one hand, the Dutch Prime Minister, Mark Rutte (VVD) was able to form a coalition Government with three other parties in the Netherlands. On the other hand, the 31-year old leader of the Austrian People’s Party (OVP), Sebastian Kurz, won the General elections in Austria. The manifesto of the next Dutch Government comes under the title “Trust in the Future” and has sarcastically been defined by dome Dutch newspapers as a “collage” of claims coming either from the Liberal D66 party, or the two Christian formations, CDA and CU. Anyhow, it took some 6 months to find a balance between the “economic” prerogatives of the VVD and the D66, on the one hand, and the “identitarian” claims of the CDU and the CU, on the other one. As a matter of fact, after the elections of 2017, The Hague and Vienna share similar views on the priorities at the EU governance level Out of the negotiations, the former obtained the simplification of the taxation scheme and greater flexibility on the job market. The latter could go back to their party bases with welfare measures targeting Dutch households and symbolic policies: allegedly, every 18 year-old citizen is set to receive a book on the history of the Netherlands. The parties agreed as well on rising levels of public investments in education, healthcare, infrastructures, security and defence. -

Austria: Vienna

Guide to Catholic-Related Records outside the U.S. about Native Americans See User Guide for help on interpreting entries Archdiocese of Vienna new 2004 AUSTRIA, VIENNA Archdiocese of Vienna Archives AT- 2 A-1010 Wollzeile 2 Wien, Oesterreich Phone 43 1 51552 http://stephanscom.at/ Hours: Monday, Tuesday, and Thursday, 8:30-1:00, 2:00-4:00; and Friday, 8:30-12:00 Access: Some restrictions apply Copying facilities: Yes History of the Leopoldine Society 1827 Bishop Edward D. Fenwick, O.P. of Cincinnati, Ohio sent Reverend John Fréderic Résé to Europe to recruit German- speaking priests and financial assistance for the Cincinnati Diocese; Reverend Samuel Mazzuchelli, O.P. (1806-1864) was among those recruited 1829 In response, the Leopoldine Society (Leopoldinen Stetiftung) was established in Vienna with headquarters at the Augustinian monastery; it solicited German- speaking priests and financial assistance from the dioceses of the Austrian Empire for needy dioceses in the United States, some of which had American Indian missions 1830-1910 The Leopoldine Society donated about $680,500 (3,402,000 kronen) to U.S. dioceses; those with Indian missions that received notable funding included Boise, Cincinnati, Detroit, Grand Rapids, Green Bay, Lead (later renamed Rapid City), Marquette, Nesqually (later renamed Seattle), Oregon (later renamed Portland in Oregon), and Tucson Before 1850 Due to efforts by the Leopoldine Society, several priests from the Austrian Empire emigrated to the United States; those who became missionaries to American Indians include Reverend Frederic I. Baraga (first bishop of the Diocese of Marquette, Michigan), Reverend Joseph F. Buh, Reverend Ignatius Mrak (second bishop of the Diocese of Marquette, Michigan), Reverend Francis Pierz, and Reverend Otto Skolla, O.F.M. -

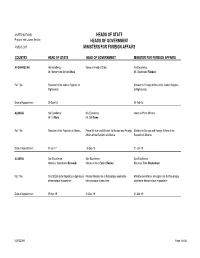

HEADS of STATE Protocol and Liaison Service HEADS of GOVERNMENT PUBLIC LIST MINISTERS for FOREIGN AFFAIRS

UNITED NATIONS HEADS OF STATE Protocol and Liaison Service HEADS OF GOVERNMENT PUBLIC LIST MINISTERS FOR FOREIGN AFFAIRS COUNTRY HEAD OF STATE HEAD OF GOVERNMENT MINISTER FOR FOREIGN AFFAIRS AFGHANISTAN His Excellency Same as Head of State His Excellency Mr. Mohammad Ashraf Ghani Mr. Salahuddin Rabbani Full Title President of the Islamic Republic of Minister for Foreign Affairs of the Islamic Republic Afghanistan of Afghanistan Date of Appointment 29-Sep-14 02-Feb-15 ALBANIA His Excellency His Excellency same as Prime Minister Mr. Ilir Meta Mr. Edi Rama Full Title President of the Republic of Albania Prime Minister and Minister for Europe and Foreign Minister for Europe and Foreign Affairs of the Affairs of the Republic of Albania Republic of Albania Date of Appointment 24-Jul-17 15-Sep-13 21-Jan-19 ALGERIA Son Excellence Son Excellence Son Excellence Monsieur Abdelkader Bensalah Monsieur Nour-Eddine Bedoui Monsieur Sabri Boukadoum Full Title Chef d'État de la République algérienne Premier Ministre de la République algérienne Ministre des Affaires étrangères de la République démocratique et populaire démocratique et populaire algérienne démocratique et populaire Date of Appointment 09-Apr-19 31-Mar-19 31-Mar-19 31/05/2019 Page 1 of 66 COUNTRY HEAD OF STATE HEAD OF GOVERNMENT MINISTER FOR FOREIGN AFFAIRS ANDORRA Son Excellence Son Excellence Son Excellence Monseigneur Joan Enric Vives Sicília Monsieur Xavier Espot Zamora Madame Maria Ubach Font et Son Excellence Monsieur Emmanuel Macron Full Title Co-Princes de la Principauté d’Andorre Chef du Gouvernement de la Principauté d’Andorre Ministre des Affaires étrangères de la Principauté d’Andorre Date of Appointment 16-May-12 21-May-19 17-Jul-17 ANGOLA His Excellency His Excellency Mr. -

Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS)

Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) BEPS Action 7 Additional Guidance on the Attribution of Profits to Permanent Establishments 4 October 2017 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS AFME and UK Finance .................................................................................................................. 5 Andrew Cousins & Richard Newby ............................................................................................... 8 Andrew Hickman ............................................................................................................................ 13 ANIE (Federazione Nazionale Imprese Elettrotecniche ed Elettroniche) ....................................... 19 Association of British Insurers ....................................................................................................... 22 BDI ...... .......................................................................................................................................... 24 BDO...... .......................................................................................................................................... 26 BEPS Monitoring Group ................................................................................................................ 29 BIAC ... .......................................................................................................................................... 47 BusinessEurope ............................................................................................................................. -

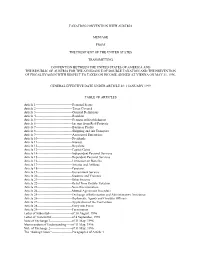

Taxation Convention with Austria Message from The

TAXATION CONVENTION WITH AUSTRIA MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES TRANSMITTING CONVENTION BETWEEN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA AND THE REPUBLIC OF AUSTRIA FOR THE AVOIDANCE OF DOUBLE TAXATION AND THE PREVENTION OF FISCAL EVASION WITH RESPECT TO TAXES ON INCOME, SIGNED AT VIENNA ON MAY 31, 1996. GENERAL EFFECTIVE DATE UNDER ARTICLE 28: 1 JANUARY 1999 TABLE OF ARTICLES Article 1----------------------------------Personal Scope Article 2----------------------------------Taxes Covered Article 3----------------------------------General Definitions Article 4----------------------------------Resident Article 5----------------------------------Permanent Establishment Article 6----------------------------------Income from Real Property Article 7----------------------------------Business Profits Article 8----------------------------------Shipping and Air Transport Article 9----------------------------------Associated Enterprises Article 10--------------------------------Dividends Article 11--------------------------------Interest Article 12--------------------------------Royalties Article 13--------------------------------Capital Gains Article 14--------------------------------Independent Personal Services Article 15--------------------------------Dependent Personal Services Article 16--------------------------------Limitation on Benefits Article 17--------------------------------Artistes and Athletes Article 18--------------------------------Pensions Article 19--------------------------------Government Service Article 20--------------------------------Students -

1 December 5, 2014 His Excellency Sebastian Kurz Federal Ministry For

December 5, 2014 His Excellency Sebastian Kurz Federal Ministry for Europe, Integration and Foreign Affairs Minoritenplatz 8 1010 Vienna Austria Dear Minister Kurz: We are writing to commend publicly the Austrian government for convening the Vienna Conference on the Humanitarian Impact of Nuclear Weapons. As members of global leadership networks developed in cooperation with the U.S.-based Nuclear Threat Initiative (NTI), we believe it is essential for governments and interested parties to state emphatically that the use of a nuclear weapon, by a state or non-state actor, anywhere on the planet would have catastrophic human consequences. Our global networks–comprised of former senior political, military and diplomatic leaders from across five continents–share many of the concerns represented on the conference agenda. In Vienna and beyond, in addition, we see an opportunity for all states, whether they possess nuclear weapons or not, to work together in a joint enterprise to identify, understand, prevent, manage and eliminate the risks associated with these indiscriminate and inhumane weapons. Specifically, we have agreed to collaborate across regions on the following four-point agenda for action and to work to shine a light on the risks posed by nuclear weapons. As we approach the 70th anniversary of the detonations over Hiroshima and Nagasaki, we pledge our support and partnership to all governments and members of civil society who wish to join our effort. Identifying Risk: We believe the risks posed by nuclear weapons and the international dynamics that could lead to nuclear weapons being used are under- estimated or insufficiently understood by world leaders. -

Low Fertility in Austria and the Czech Republic: Gradual Policy Adjustments

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Sobotka, Tomáš Working Paper Low fertility in Austria and the Czech Republic: Gradual policy adjustments Vienna Institute of Demography Working Papers, No. 2/2015 Provided in Cooperation with: Vienna Institute of Demography (VID), Austrian Academy of Sciences Suggested Citation: Sobotka, Tomáš (2015) : Low fertility in Austria and the Czech Republic: Gradual policy adjustments, Vienna Institute of Demography Working Papers, No. 2/2015, Austrian Academy of Sciences (ÖAW), Vienna Institute of Demography (VID), Vienna This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/110987 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten