Managed Expectations: EU Member States' Views on the Conference On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Letter in PDF Format the Foundation on And

Having problems in reading this e-mail? Click here Tuesday 11th September 2018 issue 815 The Letter in PDF format The Foundation on and The foundation application available on Appstore and Google Play European Union-Russia: after three lost decades, are we moving towards new cohabitation? Author: Pierre Mirel To date relations between the European Union and Russia have been based on the Partnership and Cooperation Agreement (PCA) signed in 1994 and entering into force in 1997 after ratification by the Member States and European Parliament. It established a political framework similar to the association agreements with the countries of Central Europe except that it did not include the establishment of an area of free-trade. Concluded for a period of ten years and renewed automatically yearly the PCA has been suspend for the main part. Has the time not come to think of relations with Russia differently? and on which terms? Read more Elections : Sweden Commission : Japan - Food/School Council : Budget - Economy/Finance - Travel/ETIAS - Eurogroup Parliament : European elections Diplomacy : Serbia/Kosovo Court of Auditors : Erasmus+ Germany : Brexit Austria : Ukraine Spain : Sweden - Euro zone France : Benelux - Franco-German Italy : Justice Lithuania : Poland Czech Republic : Germany Romania : Spain UK : EU- UK Macedonia : Future Council of Europe : Cyprus - Ukraine Eurostat : Growth Culture : Heritage/Days - Congress/Metz - Exhibition/Rotterdam - Art/Paris - Dance/Sevilla - Festival/Vienna Agenda | Other issues | Contact Elections : Sweden: right and left running neck and neck and the populist breakthrough not as big as forecast After the release of the first results in the Swedish general election on 9th September the blocks on the left and right are running neck and neck: 144 MPs for the left and 143 for the right. -

Dear President, Dear Ursula, We Welcome the Letter of 1 March That

March 8, 2021 Dear President, dear Ursula, We welcome the letter of 1 March that you received from Chancellor Merkel and PM Frederiksen, PM Kallas and PM Marin. We share many of the ideas outlined in the letter. Indeed, there are some points that we find are of particular importance as we work to progress the digital agenda for the EU. We certainly agree that our agenda must be founded on a good mix of self-determination and openness. Our approach to digital sovereignty must be geared towards growing digital leadership by preparing for smart and selective action to ensure capacity where called for, while preserving open markets and strengthening global cooperation and the external trade dimension. Digital innovation benefits from partnerships among sectors, promoting public and private cooperation. Translating excellence in research and innovation into commercial successes is crucial to creating global leadership. The Single Market remains key to our prosperity and to the productivity and competitiveness of European companies, and our regulatory framework needs to be made fit for the digital age. We need a Digital Single Market for innovation, to eliminate barriers to cross-border online services, and to ensure free data flows. Attention must be paid to the external dimension where we should continue to work closely with our allies around the world and where in our interest, develop new partnerships. We need to make sure that the EU can be a leader of a responsible digital transformation. Trust and innovation are two sides of the same coin. Europe’s competitiveness should be built on efficient, trustworthy, transparent, safe and responsible use of data in accordance with our shared values. -

Open Letter Chancellor Kurz

Federal Chancellor Sebastian Kurz Federal Chancellery Ballhausplatz 2 1010 Vienna Austria 27 September 2018 Sebastian Kurz, your leadership is needed to protect the youth As the former President of the World Federation of Public Health Associations, I had the privileGe to visit many countries which stronGly reduced their smokinG rate and effectively protect their non-smokers. Austria was not yet able to do so. Now, I also have the Good fortune of havinG a younG man from Austria livinG in my home as part of a Student Exchange Scheme. I am concerned for his health and the health of his siblinGs, his friends and his fellow Austrians. That’s why I would like to share some of our experiences from Australia. Smoking in Austria and Australia The followinG OECD data show the ‘daily smokinG rates’ in our countries. Since the 1970s, there are sliGhtly more smokers in Austria but two-thirds less smokers in Australia: Source: https://data.oecd.orG/healthrisk/daily-smokers.htm This marked contrast is also seen in youth smokers. In Austria, 27% of 15 year olds were smokers in 2013. In Australia, younG people are now overwhelminGly rejectinG all forms of smokinG. In 2014 the percentaGe of i secondary students aGed 15 years who smoked tobacco was less than 5% . The latest statistics indicate that this has reduced even further, so that in 2016 less than 1% of 12-15 year olds had ever tried smokinGii. What could Austria learn from Australia? There are several lessons that can be learnt from the persistent approach taken by Australian governments. -

With Kurz and Rutte, Merkel Won Allies in Reshaping the EU by Maurizio Ferrera and Alexander Damiano Ricci

With Kurz and Rutte, Merkel won allies in reshaping the EU By Maurizio Ferrera and Alexander Damiano Ricci After the electoral successes of Emmanuel Macron in France and Angela Merkel in Germany, two new political events defined the contours of the new political playground in Europe. On the one hand, the Dutch Prime Minister, Mark Rutte (VVD) was able to form a coalition Government with three other parties in the Netherlands. On the other hand, the 31-year old leader of the Austrian People’s Party (OVP), Sebastian Kurz, won the General elections in Austria. The manifesto of the next Dutch Government comes under the title “Trust in the Future” and has sarcastically been defined by dome Dutch newspapers as a “collage” of claims coming either from the Liberal D66 party, or the two Christian formations, CDA and CU. Anyhow, it took some 6 months to find a balance between the “economic” prerogatives of the VVD and the D66, on the one hand, and the “identitarian” claims of the CDU and the CU, on the other one. As a matter of fact, after the elections of 2017, The Hague and Vienna share similar views on the priorities at the EU governance level Out of the negotiations, the former obtained the simplification of the taxation scheme and greater flexibility on the job market. The latter could go back to their party bases with welfare measures targeting Dutch households and symbolic policies: allegedly, every 18 year-old citizen is set to receive a book on the history of the Netherlands. The parties agreed as well on rising levels of public investments in education, healthcare, infrastructures, security and defence. -

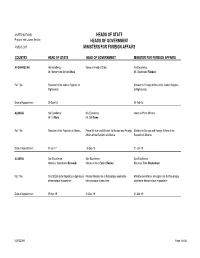

HEADS of STATE Protocol and Liaison Service HEADS of GOVERNMENT PUBLIC LIST MINISTERS for FOREIGN AFFAIRS

UNITED NATIONS HEADS OF STATE Protocol and Liaison Service HEADS OF GOVERNMENT PUBLIC LIST MINISTERS FOR FOREIGN AFFAIRS COUNTRY HEAD OF STATE HEAD OF GOVERNMENT MINISTER FOR FOREIGN AFFAIRS AFGHANISTAN His Excellency Same as Head of State His Excellency Mr. Mohammad Ashraf Ghani Mr. Salahuddin Rabbani Full Title President of the Islamic Republic of Minister for Foreign Affairs of the Islamic Republic Afghanistan of Afghanistan Date of Appointment 29-Sep-14 02-Feb-15 ALBANIA His Excellency His Excellency same as Prime Minister Mr. Ilir Meta Mr. Edi Rama Full Title President of the Republic of Albania Prime Minister and Minister for Europe and Foreign Minister for Europe and Foreign Affairs of the Affairs of the Republic of Albania Republic of Albania Date of Appointment 24-Jul-17 15-Sep-13 21-Jan-19 ALGERIA Son Excellence Son Excellence Son Excellence Monsieur Abdelkader Bensalah Monsieur Nour-Eddine Bedoui Monsieur Sabri Boukadoum Full Title Chef d'État de la République algérienne Premier Ministre de la République algérienne Ministre des Affaires étrangères de la République démocratique et populaire démocratique et populaire algérienne démocratique et populaire Date of Appointment 09-Apr-19 31-Mar-19 31-Mar-19 31/05/2019 Page 1 of 66 COUNTRY HEAD OF STATE HEAD OF GOVERNMENT MINISTER FOR FOREIGN AFFAIRS ANDORRA Son Excellence Son Excellence Son Excellence Monseigneur Joan Enric Vives Sicília Monsieur Xavier Espot Zamora Madame Maria Ubach Font et Son Excellence Monsieur Emmanuel Macron Full Title Co-Princes de la Principauté d’Andorre Chef du Gouvernement de la Principauté d’Andorre Ministre des Affaires étrangères de la Principauté d’Andorre Date of Appointment 16-May-12 21-May-19 17-Jul-17 ANGOLA His Excellency His Excellency Mr. -

1 December 5, 2014 His Excellency Sebastian Kurz Federal Ministry For

December 5, 2014 His Excellency Sebastian Kurz Federal Ministry for Europe, Integration and Foreign Affairs Minoritenplatz 8 1010 Vienna Austria Dear Minister Kurz: We are writing to commend publicly the Austrian government for convening the Vienna Conference on the Humanitarian Impact of Nuclear Weapons. As members of global leadership networks developed in cooperation with the U.S.-based Nuclear Threat Initiative (NTI), we believe it is essential for governments and interested parties to state emphatically that the use of a nuclear weapon, by a state or non-state actor, anywhere on the planet would have catastrophic human consequences. Our global networks–comprised of former senior political, military and diplomatic leaders from across five continents–share many of the concerns represented on the conference agenda. In Vienna and beyond, in addition, we see an opportunity for all states, whether they possess nuclear weapons or not, to work together in a joint enterprise to identify, understand, prevent, manage and eliminate the risks associated with these indiscriminate and inhumane weapons. Specifically, we have agreed to collaborate across regions on the following four-point agenda for action and to work to shine a light on the risks posed by nuclear weapons. As we approach the 70th anniversary of the detonations over Hiroshima and Nagasaki, we pledge our support and partnership to all governments and members of civil society who wish to join our effort. Identifying Risk: We believe the risks posed by nuclear weapons and the international dynamics that could lead to nuclear weapons being used are under- estimated or insufficiently understood by world leaders. -

HIGH-LEVEL POLITICAL FORUM 2021 Statement by the Republic of Austria Delivered by Federal Minister for the EU and Constitution

HIGH-LEVEL POLITICAL FORUM 2021 Statement by the Republic of Austria Delivered by Federal Minister for the EU and Constitution at the Federal Chancellery of Austria H.E. Karoline EDTSTADLER New York, July 2021 Check against delivery Excellencies, Ladies and Gentlemen, COVID 19 has plainly shown the importance of resilience and sustainability. The 2030 Agenda and SDGs, as agreed upon all Member States of the United Nations, form an important long-term framework for recovery strategies. The current challenges make it no longer a choice, but a necessity to accelerate innovative and decisive joint actions. Multilateralism, including EU efforts, is the necessary course of action. This pandemic highlights that we are all "in the same boat". This is the reason why we have to bear in mind that the 2030 Agenda and the Sustainable Development Goals have no borders by principle. They are a compass for decision-making and set out the issues that are viable for the future of our societies and the planet. At the same time, they contain a very strong potential for increased competitiveness and innovation. Austria’s commitment to the SDGs at all levels demonstrates that this agenda is of great importance to us: • Austria is very honoured that Chancellor Sebastian Kurz has been invited to open this year’s Ministerial Segment of the HLPF. • I have the pleasure to transmit this national statement for the general debate on behalf of Austria for the second time in a row. • Moreover, Austria was honoured to serve as co-facilitator of the recent ECOSOC/High-level Political Forum Review process. -

Merkel Pledges to Rebuild 'Devastated' Flood-Hit Areas

World Monday, July 19, 2021 05 UNESCO pursues plan to classify Great Barrier Reef as ‘endangered’ DPA The director and the To prevent it from be- and its impact on World Her- World Heritage sites world- BEIJING president of the 44th session, ing red-listed, the Australian itage are an important topic wide. China’s Vice Minister of Edu- government had invited more at the meeting in Fuzhou. The Currently, 53 World Herit- DESPITE opposition in Aus- cation Tian Xuejun, dismissed than a dozen ambassadors on director of the World Herit- age sites are classified as en- tralia, the UNESCO World speculation that the move was a snorkelling trip to the reef age Committee stressed that dangered. Heritage Committee is push- related to political tensions ahead of the meeting. the idea of the List of Endan- For the first time in the ing ahead with plans to classify between China and Australia. Nine of the 15 diplomats gered Sites is “a call to action” history of the World Heritage the Great Barrier Reef, threat- were from countries that in which the entire world com- Convention, two sites could ened by climate change, as an The Great Barrier Reef off would have voting rights at munity should cooperate. lose their title at the session. endangered natural site, the the committee’s meeting, Ernesto Ottone, the UN The Liverpool waterfront, committee’s director Mechtild the east coast of Australia Australian news agency AAP agency’s department head in for example, is to be discussed Roessler said on Sunday. stretches over more than reported. -

Austria | Freedom House

Austria | Freedom House https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/2019/austria A. ELECTORAL PROCESS: 12 / 12 A1. Was the current head of government or other chief national authority elected through free and fair elections? 4 / 4 Executive elections in Austria are generally free and fair. The president is elected for a six-year term and has predominantly ceremonial duties. The president does, however, appoint the chancellor, who also needs the support of the legislature to govern. Austria’s current president is the former head of the Green Party, Alexander Van der Bellen, who was elected after a close and controversial poll that featured a repeat of the run-off between Van der Bellen and FPÖ candidate Norbert Hofer. The run-off was repeated after the Constitutional Court established that there had been problems with the handling of postal ballots. Following the 2017 elections to the National Council (Nationalrat), the lower house of parliament, ÖVP head Sebastian Kurz became chancellor with support of the right- wing, populist FPÖ. A2. Were the current national legislative representatives elected through free and fair elections? 4 / 4 Legislative elections in Austria are generally considered credible. The National Council has 183 members chosen through proportional representation at the district, state, and federal levels. Members serve five-year terms. The 62 members of the upper house, the Federal Council (Bundesrat), are chosen by state legislatures for five- or six-year terms. Snap elections to the National Council took place in 2017, one year early, following the collapse of the coalition between the SPÖ and the ÖVP. Animosities between the two former coalition partners were reflected in an antagonistic, heavily-fought election campaign. -

19Th Viennese Ball: Saturday, March 2, 2019; 5:30Pm - Midnight

HC Newsletter January 2019 Dear Friends of Austria! Winter! Skiseason! Longing for “Wedeln” in deep powder snow? Guess, where this Photo was taken? - See answer at the end of the Newsletter! With the “Silvesterball” (New Years Eve Ball) the Ball Season started in Vienna and is in full swing by now. Here in Seattle we carry on this tradition with the annual Viennese Ball! 19th Viennese Ball: Saturday, March 2, 2019; 5:30pm - midnight This cherished tradition to let music be a tool of diplomacy, to bring people together, and to forget the problems surrounding us for a couple of hours, dates back over 200 years. The annual social highlight organized by the Austria Club of WA and held at the Nile Country Club in Mountlake Terrace, offers an elegant evening including delicious dinner, dance and voice performances, polonaise, quadrille, and of course dancing to live music until midnight! Do you want to brush up on your dance steps? From 4-5 pm just before the event, a complimentary dance lesson is offered by the USA Dance Team. Again, this year, the City of Vienna is sponsoring the event and provides traditional “Damenspenden” (gift for the ladies) with a special greeting from Vienna’s Major Michael Ludwig: "The Viennese Ball in Seattle is a special greeting from Vienna, the city on the Danube, to Seattle, the city of culture and joy of life. I wish the organizers every possible success and all guests an unforgettable evening. I hope you will have a good time waltzing the night away." - Michael Ludwig, Mayor of Vienna For more information see www.austriaclubwa.com and attached flyer. -

Austria Election Preview: Sebastian Kurz and the Rise of the Austrian ‘Anti-Party’ Page 1 of 4

LSE European Politics and Policy (EUROPP) Blog: Austria election preview: Sebastian Kurz and the rise of the Austrian ‘anti-party’ Page 1 of 4 Austria election preview: Sebastian Kurz and the rise of the Austrian ‘anti-party’ Austria goes to the polls on 15 October, with the centre-right ÖVP, led by 31-year-old Sebastian Kurz, currently ahead in the polls. Jakob-Moritz Eberl, Eva Zeglovits and Hubert Sickinger provide a comprehensive preview of the vote, writing that although polling is consistent with the idea the ÖVP and Kurz are the probable election winners, a noteworthy number of voters are still undecided. Kurz becoming the next chancellor is thus not as set in stone as Angela Merkel’s win in Germany was. Credit: Michael Tholen (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0) Austria’s last parliamentary election in September 2013 resulted in two new parties gaining parliamentary representation, the populist Team Stronach (founded by billionaire Frank Stronach) and the liberal NEOS, while the BZÖ, Jörg Haider’s party which was in government between 2002 and 2006, failed to pass the threshold for parliamentary representation. The governing parties, the Social Democrats (SPÖ) and the People’s Party (ÖVP), recorded all-time lows in support, but still formed a coalition after the election. Team Stronach, however, deteriorated into insignificance very soon afterwards. Since then, however, Austrian voters have become increasingly dissatisfied with the performance of the SPÖ- ÖVP government. Eventually, the so-called refugee crisis in 2015 led to the right-wing populist FPÖ surging into first place in the polls. Soon after, in 2016, both government parties suffered a heavy defeat in the presidential elections, when their candidates gained only around 10% of the vote each, and failed to participate in the second, decisive round of the contest. -

STATEMENT by the Republic of Moldova in Response to the Address by the Minister for Foreign Affairs of Austria, H.E

PC.DEL/1119/16 15 July 2016 ENGLISH only PERMANENT DELEGATION OF THE REPUBLIC OF MOLDOVA TO THE OSCE STATEMENT by the Republic of Moldova in response to the address by the Minister for Foreign Affairs of Austria, H.E. Mr. Sebastian Kurz (1108th Permanent Council, July 14, 2016) Mr. Chairperson, We warmly welcome H.E. Mr. Sebastian Kurz, Minister for Foreign Affairs of Austria to the Permanent Council and thank him for outlining the priorities of the in-coming Austrian OSCE Chairmanship for the next year. The Republic of Moldova has aligned with the statement delivered by the European Union. In addition, we would like to make some remarks in our national capacity. We commend Austria’s initiative to assume the Chairmanship at a very challenging time for the OSCE. For the last several years, the Organization has been confronting with an increasing number of security challenges stemming both from inside and outside the OSCE area. The unresolved protracted conflicts, the on-going crisis in and around Ukraine as well as emerging threats generated by the upsurge of terrorism, trafficking in human beings, illegal migration are just few issues that underline the importance of strengthening OSCE’s capacities to address more efficiently the old core issues and the new challenges. The OSCE is well placed to address in an inclusive and comprehensive manner the most pressing issues on the European security agenda. The up-coming Informal Ministerial meeting in Potsdam will provide the opportunity to assess where we stand now and to explore initiatives on reconsolidating security in Europe.