Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

06Dem Internationalen Steuerwettbewerb Begegnen

DEM INTERNATIONALEN STEUERWETTBEWERB 06BEGEGNEN I. Motivation II. Der Tax Cuts and Jobs Act und seine Auswirkungen 1. Wesentliche Elemente der Steuerreform 2. Makroökonomische Auswirkungen der Steuerreform III. Deutschland im internationalen Steuerwettbewerb 1. Gewinnsteuersätze international im Abwärtstrend 2. Diskriminierende Besteuerung von mobilen und immobilen Aktivitäten IV. Herausforderungen bei der internationalen Besteuerung 1. Prinzipien zur Festlegung der Besteuerungsrechte 2. Besteuerung der Digitalwirtschaft als Herausforderung 3. Alternative Harmonisierungsbestrebungen V. Steuerpolitische Optionen zur Förderung privater Investitionen 1. Moderate Senkung der Steuerbelastung 2. Abbau von Verzerrungen Eine andere Meinung Literatur Dem internationalen Steuerwettbewerb begegnen – Kapitel 6 DAS WICHTIGSTE IN KÜRZE Zu Beginn des Jahres 2018 wurde in den Vereinigten Staaten mit dem Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) eine umfangreiche Steuerreform umgesetzt, die zum einen die Steuersätze auf Arbeits- und Kapi- taleinkommen deutlich reduziert hat, zum anderen die Besteuerung multinationaler Unternehmen neu ordnet. Dies ist die größte Steuerreform seit dem Tax Reform Act 1986 und dürfte sich in viel- facher Hinsicht auf die Wirtschaft in den Vereinigten Staaten auswirken. Es ist eine zusätzliche Belebung des US-amerikanischen Wirtschaftswachstums zu erwarten, was wiederum das deut- sche Wirtschaftswachstum anregen dürfte. Mit Belgien, Frankreich und Italien haben Staaten mit ehemals höheren Steuersätzen als Deutsch- land ebenfalls die Steuersätze gesenkt und weitere Senkungen angekündigt. Bei den tariflichen Gewinnsteuersätzen rückt Deutschland damit allmählich wieder an die Spitze der OECD-Länder. Die Steuertarife sind jedoch nur ein Bestandteil eines Steuersystems. Die Bemessungsgrundlage, auf die der Steuersatz angewandt wird, ist gleichermaßen von Bedeutung. In diesem Kontext wird unter dem Begriff „Smart Tax Competition“ diskutiert, inwieweit steuerliche Anreize gezielt gesetzt werden können, um bestimmte, sehr mobile Aktivitäten anzuziehen. -

The Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center Microsimulation Model: Documentation and Methodology for Version 0304

The Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center Microsimulation Model: Documentation and Methodology for Version 0304 Jeffrey Rohaly Adam Carasso Mohammed Adeel Saleem January 10, 2005 Jeffrey Rohaly is a research associate at the Urban Institute and director of tax modeling for the Tax Policy Center. Adam Carasso is a research associate at the Urban Institute. Mohammed Adeel Saleem is a research assistant at the Urban Institute. This documentation covers version 0304 of the model, which was developed in March 2004. The authors thank Len Burman and Kim Rueben for helpful comments and suggestions and John O’Hare for providing background on statistical matching. Views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Urban Institute, the Brookings Institution, their boards, or their sponsors. Documentation and Methodology: Tax Model Version 0304 A. Introduction.................................................................................................................... 3 Overview................................................................................................................................. 3 History..................................................................................................................................... 5 B. Source Data .................................................................................................................... 7 SOI Public Use File ............................................................................................................... -

Tax Administrations and the Challenges of the Digital

LISBON TAX SUMMIT TAX ADMINISTRATIONS AND THE CHALLENGES OF THE DIGITAL WORLD 24 - 26 October 2018 Lisbon, Portugal SUMMARY REPORT LISBON TAX SUMMIT TAX ADMINISTRATIONS AND THE CHALLENGES OF DIGITAL WORLD CONTENTS DAY 1 FAIR AND EFFECTIVE TAXATION ACROSS THE DIGITAL ECONOMY 2 SESSION 1 INAUGURAL SESSION 2 SESSION 2 KEYNOTES: FAIR AND EFFECTIVE TAXATION ACROSS THE DIGITAL ECONOMY 3 SESSION 3 PANEL: HOW TO TAX DIGITAL BUSINESSES - COUNTRIES EXPERIENCES 4 SESSION 4 PANEL: TAX TRANSPARENCY IN THE DIGITAL ERA 6 SESSION 5 ROUND TABLE: DIGITAL TAXATION. IMPLICATIONS, CONCERNS ON THE POLICY AND ADMINISTRATION SIDES 7 SESSION 6 ROUND TABLE: TREATMENT OF CRYPTOCURRENCIES 14 AND INITIAL COIN OFFERINGS 8 DAY 2 MAKING TAX ADMINISTRATION DIGITAL 9 SESSION 7 KEYNOTE: MAKING TAX ADMINISTRATION DIGITAL 9 SESSION 8 PANEL: GETTING CLOSER TO THE FACTS. REAL-TIME CONTROLS FOR TAX ADMINISTRATION PURPOSES 10 SESSION 9 PANEL: PUBLIC SERVICE DELIVERY 11 SESSION 10 PANEL: HUMAN RESOURCES & CAPACITY BUILDING 13 SESSION 11 ROUND TABLE: TAX AND CUSTOMS DIGITAL ADMINISTRATIONS 14 SESSION 12 PANEL: ADVANCED ANALYTICS FOR COMPLIANCE CONTROL 15 DAY 3 VISION OF THE FUTURE: CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES OF TAX DIGITIZATION 16 SESSION 13 KEYNOTE: VISION OF THE FUTURE: CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES OF TAX DIGITIZATION 16 SESSION 14 PANEL: NEW TECHNOLOGIES TO ENHANCE TAX COMPLIANCE AND COLLECTION 17 SESSION 15 PANEL: TAX DIGITIZATION: VIEWS AND PERSPECTIVES OF BUSINESS COMMUNITY 18 SESSION 16 ROUND TABLE: TAX ADMINISTRATION IN 10 - 15 YEARS, HOW ARE WE COPING WITH THE PACE OF -

The Government of the Hungarian People's Republic

CONVENTION BETWEEN THE GOVERNMENT OF THE HUNGARIAN PEOPLE'S REPUBLIC AND THE GOVERNMENT OF THE ITALIAN REPUBLIC FOR THE AVOIDANCE OF DOUBLE TAXATION WITH RESPECT TO TAXES ON INCOME AND CAPITAL AND THE PREVENTION OF FISCAL EVASION.1 The Government of the Hungarian People's Republic and the Government of the Italian Republic, desiring to promote and facilitate the economic relations between the two countries, have agreed to conclude a Convention for the avoidance of double taxation with respect to taxes on income and capital and the prevention of fiscal evasion of which the provisions are the following: Article 1 - Personal scope This Convention shall apply to persons who are residents of one or both of the Contracting States. Article 2 - Taxes covered 1. This Convention shall apply to taxes on income and on capital imposed on behalf of each Contracting State or its political or administrative subdivisions or local authorities, irrespective of the manner in which they are levied. 2. There shall be regarded as taxes on income and on capital taxes imposed on total income, on total capital, or on elements of income or of capital, including taxes on gains from the alienation of movable or immovable property, taxes on the total amounts of wages or salaries paid by enterprises, as well as taxes on capital appreciation. 3. The existing taxes to which this Convention shall apply are the following: (a) in the case of the Italian Republic: (1) the individual income tax (imposta sul reddito delle persone fisiche); (2) the tax on the income of legal entities (imposta sul reddito delle persone giuridiche); and (3) the local income tax (imposta locale sui redditi), even if withheld at the source (hereinafter referred to as "Italian tax"); (b) in the case of the Hungarian People's Republic: (1) the income taxes (j”vedelemad¢k); (2) the profit taxes (nyeres‚gad¢k); (3) the enterprises' special tax (v llalati kl”nad¢); (4) the tax on buildings (h zad¢); 1 Date of Conclusion: 16 May 1977. -

The Little Downpayment Savings Policy That Could

This article was downloaded by: [George Mason University] On: 27 August 2015, At: 04:02 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: 5 Howick Place, London, SW1P 1WG Housing and Society Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rhas20 The little downpayment savings policy that could: revisiting building and loan societies and their products in times of the tight credit box and the pending housing finance reform Katrin Anackera a School of Policy, Government and International Affairs, 3351 Fairfax Drive, MSN 3B1, Arlington, VA 22201, USA Published online: 25 Aug 2015. Click for updates To cite this article: Katrin Anacker (2015): The little downpayment savings policy that could: revisiting building and loan societies and their products in times of the tight credit box and the pending housing finance reform, Housing and Society, DOI: 10.1080/08882746.2015.1076128 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08882746.2015.1076128 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. -

Optimal Benefit-Based Corporate Income

Optimal Benefit-Based Corporate Income Tax Simon M Naitram∗ Adam Smith Business School, University of Glasgow June 26, 2019 Abstract I derive an optimal benefit-based corporate tax rate formula as a function of the public input elasticity of profits and the (net of) tax elasticity of profits. I argue that the existence of the corporate income tax should be justified by the benefit-based view of taxation: firms should pay tax according to the benefits they receive from the use of the public input. I argue that benefit-based corporate taxation is normatively fair. Since the public input is a location-specific factor, a positive benefit-based corporate tax rate is also feasible even in a small open economy. The benefit-based view gives three clear principles of corporate tax design. First, we should tax corporate profits at source. Second, the optimal tax base is location-specific rents. Third, profit shifting is normatively wrong. An empirical application of the formula suggests the optimal benefit-based corporate tax rate on public corporations in the United States lies in the range of 35 to 52 percent. JEL: H21; H25; H32; H41 Keywords: benefit principle; optimal corporate tax; public input 1 Introduction The view that `corporations must pay their fair share' dominates public opinion. In 2017, Amer- icans' biggest complaint about the federal tax system was the feeling that some corporations do not pay their fair share of tax. Sixty-two percent of respondents said they were bothered `a lot' by corporations who did not pay their fair share (Pew Research Center, 2017a). -

The Relationship Between MNE Tax Haven Use and FDI Into Developing Economies Characterized by Capital Flight

1 The relationship between MNE tax haven use and FDI into developing economies characterized by capital flight By Ali Ahmed, Chris Jones and Yama Temouri* The use of tax havens by multinationals is a pervasive activity in international business. However, we know little about the complementary relationship between tax haven use and foreign direct investment (FDI) in the developing world. Drawing on internalization theory, we develop a conceptual framework that explores this relationship and allows us to contribute to the literature on the determinants of tax haven use by developed-country multinationals. Using a large, firm-level data set, we test the model and find a strong positive association between tax haven use and FDI into countries characterized by low economic development and extreme levels of capital flight. This paper contributes to the literature by adding an important dimension to our understanding of the motives for which MNEs invest in tax havens and has important policy implications at both the domestic and the international level. Keywords: capital flight, economic development, institutions, tax havens, wealth extraction 1. Introduction Multinational enterprises (MNEs) from the developed world own different types of subsidiaries in increasingly complex networks across the globe. Some of the foreign host locations are characterized by light-touch regulation and secrecy, as well as low tax rates on financial capital. These so-called tax havens have received widespread media attention in recent years. In this paper, we explore the relationship between tax haven use and foreign direct investment (FDI) in developing countries, which are often characterized by weak institutions, market imperfections and a propensity for significant capital flight. -

Business Disruption: Transfer Pricing Issues and Considerations for the Real Estate Investment Trust Industry

Tax Insights from Transfer Pricing and Real Estate Business Disruption: Transfer pricing issues and considerations for the real estate investment trust industry May 5, 2020 In brief The current crisis has caused significant business disruption for almost every industry, but with particular impact on certain industries. Many real estate investment trusts (REITs) face difficulties as their tenants struggle to meet lease obligations, their real estate assets decline in value, and the ability of their employees to work remotely is challenged. Like many other businesses, REITs must adjust their operations to deal with business disruption arising from the current environment. For a REIT that has taxable REIT subsidiaries (TRSs), its transfer pricing policies can play a key role in its ability to respond to these challenges. This is because TRSs provide REITs with the increased operational flexibility to enter into transactions that may not be permissible for the REIT itself. However, when REITs enter into — or revise — transactions with TRSs based on changes in market conditions, careful consideration should be given to the rules governing the taxation of REITs and TRSs under Sections 856 and 857, as well as the transfer pricing rules under Section 482. Not doing so could result in unexpected excise taxes, REIT compliance concerns, and liquidity issues. The following summarizes common transactions between REITs and TRSs and key issues that should be considered from an income tax perspective. In detail Leases of property from a REIT to a TRS Leases from REITs to TRSs are prevalent where a REIT holds certain classes of property, such as hotels or assisted living facilities. -

2013 Individual Income Tax Rates, Standard Deductions, Personal Exemptions, and Filing Thresholds

15-Oct-15 2016 Individual Income Tax Rates, Standard Deductions, Personal Exemptions, and Filing Thresholds If your filing status is Single If your filing status is Married filing jointly Taxable Income Taxable Income But not But not Over --- over --- Marginal Rate Over --- over --- Marginal Rate $0 $9,275 10% $0 $18,550 10% $9,275 $37,650 15% $18,550 $75,300 15% $37,650 $91,150 25% $75,300 $151,900 25% $91,150 $190,150 28% $151,900 $231,450 28% $190,150 $413,350 33% $231,450 $413,350 33% $413,350 $415,050 35% $413,350 $466,950 35% $415,050 and over 39.6% $466,950 and over 39.6% If your filing status is Married filing If your filing status is Head of Household separately Taxable Income Taxable Income But not But not Over --- over --- Marginal Rate Over --- over --- Marginal Rate $0 $13,250 10% $0 $9,275 10% $13,250 $50,400 15% $9,275 $37,650 15% $50,400 $130,150 25% $37,650 $91,150 25% $130,150 $210,800 28% $91,150 $190,150 28% $210,800 $413,350 33% $190,150 $413,350 33% $413,350 $441,000 35% $413,350 $441,000 35% $441,000 and over 39.6% $441,000 and over 39.6% Standard Deduction Standard Deduction for Dependents Standard Blind/Elderly Greater of $1000 or sum of $350 and Single $6,300 $1,550 individual's earned income Married filing jointly $12,600 $1,250 Personal Exemption $4,050 Head of Household $9,300 $1,550 Married filing Threshold for Refundable separately $6,300 $1,250 Child Tax Credit $3,000 Filing Threshold Number of Blind / Elderly Exemptions 0 1 2 3 4 Single 10,350 11,900 13,450 Head of Household 13,350 14,900 16,450 Married -

Taxation Convention with Austria Message from The

TAXATION CONVENTION WITH AUSTRIA MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES TRANSMITTING CONVENTION BETWEEN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA AND THE REPUBLIC OF AUSTRIA FOR THE AVOIDANCE OF DOUBLE TAXATION AND THE PREVENTION OF FISCAL EVASION WITH RESPECT TO TAXES ON INCOME, SIGNED AT VIENNA ON MAY 31, 1996. GENERAL EFFECTIVE DATE UNDER ARTICLE 28: 1 JANUARY 1999 TABLE OF ARTICLES Article 1----------------------------------Personal Scope Article 2----------------------------------Taxes Covered Article 3----------------------------------General Definitions Article 4----------------------------------Resident Article 5----------------------------------Permanent Establishment Article 6----------------------------------Income from Real Property Article 7----------------------------------Business Profits Article 8----------------------------------Shipping and Air Transport Article 9----------------------------------Associated Enterprises Article 10--------------------------------Dividends Article 11--------------------------------Interest Article 12--------------------------------Royalties Article 13--------------------------------Capital Gains Article 14--------------------------------Independent Personal Services Article 15--------------------------------Dependent Personal Services Article 16--------------------------------Limitation on Benefits Article 17--------------------------------Artistes and Athletes Article 18--------------------------------Pensions Article 19--------------------------------Government Service Article 20--------------------------------Students -

Tax Policy State and Local Individual Income Tax

TAX POLICY CENTER BRIEFING BOOK The State of State (and Local) Tax Policy SPECIFIC STATE AND LOCAL TAXES How do state and local individual income taxes work? 1/9 Q. How do state and local individual income taxes work? A. Forty-one states and the District of Columbia levy broad-based taxes on individual income. New Hampshire and Tennessee tax only individual income from dividends and interest. Seven states do not tax individual income of any kind. Local governments in 13 states levy some type of tax on income in addition to the state income tax. State governments collected $344 billion from individual income taxes in 2016, or 27 percent of state own-source general revenue (table 1). “Own-source” revenue excludes intergovernmental transfers. Local governments—mostly concentrated in Maryland, New York, Ohio, and Pennsylvania—collected just $33 billion from individual income taxes, or 3 percent of their own-source general revenue. (Census includes the District of Columbia’s revenue in the local total.) TABLE 1 State and Local Individual Income Tax Revenue 2016 Revenue (billions) Percentage of own-source general revenue State and local $376 16% State $344 27% Local $33 3% Source: Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center, “State and Local Finance Initiative Data Query System.” Note: Own-source general revenue does not include intergovernmental transfers. Forty-one states and the District of Columbia levy a broad-based individual income tax. New Hampshire taxes only interest and dividends, and Tennessee taxes only bond interest and stock dividends. (Tennessee is phasing its tax out and will completely eliminate it in 2022.) Alaska, Florida, Nevada, South Dakota, Texas, Washington, and Wyoming do not have a state individual income tax. -

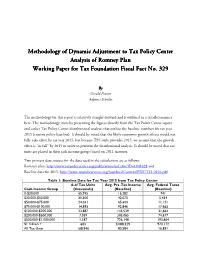

Methodology of Dynamic Adjustment to Tax Policy Center Analysis of Romney Plan Working Paper for Tax Foundation Fiscal Fact No

Methodology of Dynamic Adjustment to Tax Policy Center Analysis of Romney Plan Working Paper for Tax Foundation Fiscal Fact No. 329 ByByBy Gerald Prante Adjunct Scholar The methodology for this report is relatively straight-forward and is outlined in a detailed manner here. The methodology starts by presenting the figures directly from the Tax Policy Center report and earlier Tax Policy Center distributional analysis that outline the baseline numbers for tax year 2015 (current policy baseline). It should be noted that the likely economic growth effects would not fully take effect by tax year 2015, but because TPC only provides 2015, we assume that the growth effect is “in full” by 2015 in order to perform the distributional analysis. It should be noted that tax units are placed in their cash income groups based on 2011 incomes. Two primary data sources for the data used in the calculations are as follows: Romney plan: http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/publications/url.cfm?ID=1001628 and Baseline data for 2015: http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/numbers/Content/PDF/T12-0126.pdf . Table 1: Baseline Data for Tax Year 2015 from Tax Policy Center # of Tax Units Avg. Pre -Tax Income Avg. Federal Taxes Cash Income Group (thousands) (Baseline) (Baseline) 0-$30,000 65,745 16,282 741 $30,000 -$50,000 30,300 42,073 5,454 $50,000 -$75,000 24,031 65,604 11,121 $75,000 -$100,000 14,893 92,846 17,663 $100,000 -$200,000 23,887 145,539 31,662 $200,000 -$500,000 7,059 305,065 74,677 $500,000 -$1,000,000 1,187 726,148 193,864 $1 million + 603 3,088,329 970,172 All Tax Units 168,946 80,584 16,851 Table 2: Static Distributional Estimates of Romney Plan from TPC Report Avg.