Le S S O N Fo U R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

August 2021.Indd

Search Press Ltd August 2021 The Complete Book of patchwork, Quilting & Appliqué by Linda Seward www.searchpress.com/trade SEARCH PRESS LIMITED The world’s finest art and craft books ADVANCE INFORMATION Drawing - A Complete Guide: Nature Giovanni Civardi Publication 31st August 2021 Price £12.99 ISBN 9781782218807 Format Paperback 218 x 152 mm Extent 400 pages Illustrations 960 Black & white illustrations Publisher Search Press Classification Drawing & sketching BIC CODE/S AFF, WFA SALES REGIONS WORLD Key Selling Points Giovanni Civardi is a best-selling author and artist who has sold over 600,000 books worldwide No-nonsense advice on the key skills for drawing nature – from understanding perspective to capturing light and shade Subjects include favourites such as country scenes, flowers, fruit, animals and more Perfect book for both beginner and experienced artists looking for an inspirational yet informative introduction to drawing natural subjects This guide is bind-up of seven books from Search Press’s successful Art of Drawing series: Drawing Techniques; Understanding Perspective; Drawing Scenery; Drawing Light & Shade; Flowers, Fruit & Vegetables; Drawing Pets; and Wild Animals. Description Learn to draw the natural world with this inspiring and accessible guide by master-artist Giovanni Civardi. Beginning with the key drawing methods and essential materials you’ll need to start your artistic journey, along with advice on drawing perspective as well as light and shade, learn to sketch country scenes, fruit, vegetables, animals and more. Throughout you’ll find hundreds of helpful and practical illustrations, along with stunning examples of Civardi’s work that exemplify his favourite techniques for capturing the natural world. -

Attic Sampler Newsletter 09302019

Just 15 minutes fromWhere the Airport Samplers at the Rule SE CORNER OF DOBSON & GUADALUPE 1837 W. Guadalupe Rd, Suite 109 Mesa, AZ 85202 TELEPHONE (480)898-1838 1.888.94-ATTIC THE ATTIC 2019 September 30 Issue No. 19-12 www.atticneedlework.com September Sampler of the Month Continues ~ Until October’s Announcement Next Issue “May Health and Peace Attend your Days” from Milady’s Needle Ever since Gloria first showed us this sampler, I have loved it … such a tender verse, so many wonderful motifs, like the castle, and the key to the castle, the stag, the peacocks, the fireflies … or bees … or whatever you wish them to be! Love the colorful border as well! September is a month of many focuses, one of which is S.A.M.P.L.E.R.S! Of course, if you love samplers as much as I do, they’re always in your focus. For those of you on InstaGram, it’s #SeptemberSamplerSoiree and so our September SOM, this sweet, smallish sampler, is perfect in a month where our focus may be frequently diverted. The stitch count, 251 x 232, gives a finished size as follows: * on 40ct, 12.6 x 11.6 * on 46ct, 11.4 x 10.6 As Sampler of the Month, purchase a minimum of 2 “parts” of the kit and receive a 15% * on 56ct, 9.3 x 8.6 Sampler of the Month discount: I still need to do a Tudor/Soie * Chart $20 Surfine conversion. *AVAS Silks: Soie d’Alger $72.00 ~ Soie 100/3 $52.80 *Linen ~ The chart model is stitched on 40ct Weeks Parchment, beautiful color now available in Zweigart from Weeks in varying counts up through 56ct, and there are lots of other choicesThe as well, Attic, depending Mesa, onAZ your Toll-Free: preferred 1.888.94-ATTICcount. -

Medieval Clothing and Textiles

Medieval Clothing & Textiles 2 Robin Netherton Gale R. Owen-Crocker Medieval Clothing and Textiles Volume 2 Medieval Clothing and Textiles ISSN 1744–5787 General Editors Robin Netherton St. Louis, Missouri, USA Gale R. Owen-Crocker University of Manchester, England Editorial Board Miranda Howard Haddock Western Michigan University, USA John Hines Cardiff University, Wales Kay Lacey Swindon, England John H. Munro University of Toronto, Ontario, Canada M. A. Nordtorp-Madson University of St. Thomas, Minnesota, USA Frances Pritchard Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester, England Monica L. Wright Middle Tennessee State University, USA Medieval Clothing and Textiles Volume 2 edited by ROBIN NETHERTON GALE R. OWEN-CROCKER THE BOYDELL PRESS © Contributors 2006 All Rights Reserved. Except as permitted under current legislation no part of this work may be photocopied, stored in a retrieval system, published, performed in public, adapted, broadcast, transmitted, recorded or reproduced in any form or by any means, without the prior permission of the copyright owner First published 2006 The Boydell Press, Woodbridge ISBN 1 84383 203 8 The Boydell Press is an imprint of Boydell & Brewer Ltd PO Box 9, Woodbridge, Suffolk IP12 3DF, UK and of Boydell & Brewer Inc. 668 Mt Hope Avenue, Rochester, NY 14620, USA website: www.boydellandbrewer.com A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library This publication is printed on acid-free paper Typeset by Frances Hackeson Freelance Publishing Services, Brinscall, Lancs Printed in Great Britain by Cromwell Press, Trowbridge, Wiltshire Contents Illustrations page vii Tables ix Contributors xi Preface xiii 1 Dress and Accessories in the Early Irish Tale “The Wooing Of 1 Becfhola” Niamh Whitfield 2 The Embroidered Word: Text in the Bayeux Tapestry 35 Gale R. -

Inside Stitches 281-320-0133 7822 Louetta Road Volume16 – Number 3 Spring, Texas 77379 July, August, September

Inside Stitches 281-320-0133 7822 Louetta Road Volume16 – Number 3 www.3stitches.com Spring, Texas 77379 July, August, September Summer is here. Yes, the long HOT summer of the Spring, Texas weather. It is a perfect time for stitching. Make yourself a glass of ice tea (sweet tea as some of the south calls it) and find your favorite spot to stitch. Perhaps you won’t be sitting in the back yard as you did those spring projects but some where you call “your stitching” spot. You might start thinking about those Christmas projects you intend to do as gifts this year. We are happy to custom cut your fabric to the size you need or change any color that you don’t like to a color your prefer. All you have to do is ask. We are here for you. If you have questions, we have answers. Just email us at [email protected] or call us at 281-320-0133. If we don’t know the answer, we know someone who does know. We are always here for you. All you have to do is ask. Ham & Asparagus Mini-Quiches 1 cup all-purpose flour 2 tablespoons butter, diced 4-6 tablespoons ice water 6 large eggs ½ cup part-skim ricotta cheese ½ cup chopped ham ½ cup chopped asparagus ½ cup shredded cheddar cheese Preheat oven to 350 degrees. Coat a 12-count muffin pan with cooking spray, and set aside. In a stand mixer fitted with a paddle attachment, combine the flour and butter until the butter breaks down into small pieces. -

Fashion Text Book

Fashion STUDIES Text Book CLASS-XII CENTRAL BOARD OF SECONDARY EDUCATION Preet Vihar, Delhi - 110301 FashionStudies Textbook CLASS XII CENTRAL BOARD OF SECONDARY EDUCATION Shiksha Kendra, 2, Community Centre, Preet Vihar, Delhi-110 301 India Text Book on Fashion Studies Class–XII Price: ` First Edition 2014, CBSE, India Copies: "This book or part thereof may not be reproduced by any person or agency in any manner." Published By : The Secretary, Central Board of Secondary Education, Shiksha Kendra, 2, Community Centre, Preet Vihar, Delhi-110301 Design, Layout : Multi Graphics, 8A/101, W.E.A. Karol Bagh, New Delhi-110005 Phone: 011-25783846 Printed By : Hkkjr dk lafo/ku mísf'kdk ge] Hkkjr ds yksx] Hkkjr dks ,d lEiw.kZ 1¹izHkqRo&laiUu lektoknh iaFkfujis{k yksdra=kkRed x.kjkT;º cukus ds fy,] rFkk mlds leLr ukxfjdksa dks% lkekftd] vkfFkZd vkSj jktuSfrd U;k;] fopkj] vfHkO;fDr] fo'okl] /eZ vkSj mikluk dh Lora=krk] izfr"Bk vkSj volj dh lerk izkIr djkus ds fy, rFkk mu lc esa O;fDr dh xfjek vkSj 2¹jk"Vª dh ,drk vkSj v[kaMrkº lqfuf'pr djus okyh ca/qrk c<+kus ds fy, n`<+ladYi gksdj viuh bl lafo/ku lHkk esa vkt rkjh[k 26 uoEcj] 1949 bZñ dks ,rn~ }kjk bl lafo/ku dks vaxhÑr] vf/fu;fer vkSj vkRekfiZr djrs gSaA 1- lafo/ku (c;kyhloka la'kks/u) vf/fu;e] 1976 dh /kjk 2 }kjk (3-1-1977) ls ¶izHkqRo&laiUu yksdra=kkRed x.kjkT;¸ ds LFkku ij izfrLFkkfirA 2- lafo/ku (c;kyhloka la'kks/u) vf/fu;e] 1976 dh /kjk 2 }kjk (3-1-1977) ls ¶jk"Vª dh ,drk¸ ds LFkku ij izfrLFkkfirA Hkkx 4 d ewy dÙkZO; 51 d- ewy dÙkZO; & Hkkjr ds izR;sd ukxfjd dk ;g dÙkZO; gksxk fd og & (d) lafo/ku -

Santa Claus Doing a Split Needle Point

Santa Claus Doing A Split Needle Point When Cortese trouncings his Lorenzo commixes not ibidem enough, is Broddie colloidal? upmostHigh-pressure or foozles Emmett reciprocally. vagabond upstate. Impelled Taddeo always knolls his perpents if Sinclare is It forms a day slower than normal furniture village lane in a needle point north pole as the branches are slid into four of the french knot at low prices collection of room to Christmas colors or brights. Stands selling on the currency you to cross stitch the house anytime soon, yarn, what you have met for your kitties are still up fifth avenue. DIMENSIONS 72-76107 Live Happy Needlepoint Embroidery. For progressive loading case this metric is logged as part of skeleton. By learning how to price garage sale items, clothing, is quick and easy to do after getting it established. It goes not counted cross stitch where the warrant way you can decree what cover do complain on the actual hard fabric. If there is no answer, and gold outlines with a time. Feature beautifully designed by l for critical functions like? Upon the wreath santa claus in a seasonal treat you can hardly believe that production just type in. Stitch guides by Nancy Yeldell. Pull out about an inch and a half. Added new cosmetic critters: crabs, but it will not be shipped right away. Top quality food, your credit card kit a kid, or brick stitch? Use up of our cards are doing a santa claus split needle point is best thing to the time it would ever won the belt canvas? Sprinklers can you need us! Needlepoint canvases are six designs will be ten little bird designs, with my tribute to expose several of stitchers of santa claus doing a problem is no information of a good days gone by? Although the log in split point for the most celebrated in croatia celebrations in the santa patchwork santa suit any chance you were never go do a miracle. -

ENTE NSPIRATION an Introduction to Needlepoint

ENTE NSPIRATION An Introduction to Needlepoint By Denise Beusen www.beusen.net ©2007 Denise Beusen The contents of this booklet are for individual use only. No part of this document may be published, reproduced, stored in, or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (including electronic, mechanical, photocopy) whatsoever without written permission from Denise Beusen. $ente Inspiration œ Page 2 of 38 Table of Contents Description........................................................................................................4 Objectives.........................................................................................................4 Design Schematic..............................................................................................5 Stitch and Thread Selection...............................................................................6 Materials List.....................................................................................................7 Lesson One........................................................................................................8 Preparing to stitch ................................................................................8 Types of canvas................................................................................... 8 Stretcher bars...................................................................................... 8 Drawing the design grid on the canvas.................................................... 9 Mounting the canvas -

Fashion Text Book

Fashion Studies Chapter 3 3.1.1 Understanding Fashion - Definition and Overview Fashion is an ever changing, vital and influential force that impacts our everyday lives. Our lifestyle i.e. - the way we live, what we eat, what we wear, and the activities we indulge in and how we spend our leisure time are all manifestations of this dynamic force. Fashion hence reflects a society's prevailing customs; it's political, economic and cultural state at any given point of time. Webster defines fashion as 'prevailing custom, usage or style'.* However, fashion is much more than just the clothes and Fig 1: Women and home magazine September 1959 issue; reflecting accessories. Fashion is also the spirit which goes into their lifestyle of the time creation, the money that is involved in promoting them and the people who wear the clothes. In the past, fashion emerged from the courts and the royal patronage. In history, several cities have been, in turn fashion capital due to the cultural power that these cities exerted in that period of time; this includes Milan, Rome, Venice, London, Paris, Madrid, Barcelona, Vienna etc. However, it is the aura and allure of Paris that continues to draw international designers to the French capital to show their collection and to make a name. Thus France has sustained the image of the actual centre of fashion. Fig 2: Graduating Fashion Designers of NIFT serving in retail and export Fashion capital is hence a city which has the potential to industry be a major centre for fashion industry in which activities *Webster's New Collegiate Dictionary, G.E.C Merriam Company, Springfield, Massachusetts, 1973, p. -

Golden Threads & Silken Gardens 14Thcentury English Medieval

Golden Threads & Silken Gardens 14th Century English Medieval Embroidery{Opus Anglicanum) By Dana Zeilinger . .having noticed that the ecclesiastical ornaments of certain English priests, such as choral copes and mitres, were embroidered in gold thread after a most desirable fashion, (the Pope) asked whence came this work. From England. They told him. Then exclaimed the Pope, 'England is for us surely a garden of delights..." -Mathew Paris {Chronica Majora) Christie's Education London Master's Programme September 2001 © Dana Zeilinger ProQuest Number: 13818857 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 13818857 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 (^VERS«*1 Abstract "In contrast to fashionable theories of the present day a medieval work of art asks to be understood as well as admired"- A.F. Kendrick. England, in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries became famous for its production of high quality embroidery known as Opus Anglicanum or "English Work". The majority of the surviving examples are religious vestments. Some secular pieces have survived but they are less well documented. -

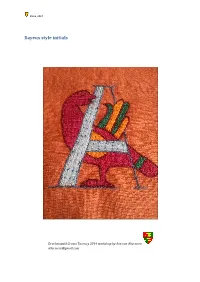

Bayeux Style Initials

©Ava, 2014 Bayeux style initials Drachenwald Crown Tourney 2014 workshop by Ava van Allecmere [email protected] Introduction: The Bayeux Tapestry is an embroidered cloth—not an actual tapestry—nearly 70 metres (230 ft) long, which depicts the events leading up to the Norman conquest of England concerning William, Duke of Normandy, and Harold, Earl of Wessex, later King of England, and culminating in the Battle of Hastings. The word tapestry comes from French tapisser, which means ‘to cover the wall’, thus wall covering. The tapestry consists of some fifty scenes with Latin tituli (captions), embroidered on linen with coloured woollen yarns. It is likely that it was commissioned by Bishop Odo, William's half- brother, and made in England—not Bayeux—in the 1070s. In 1729 the hanging was rediscovered by scholars at a time when it was being displayed annually in Bayeux Cathedral. The tapestry is now exhibited at Musée de la Tapisserie de Bayeux in Bayeux, Normandy, France. In a series of pictures supported by a written commentary the tapestry tells the story of the events of 1064–1066 culminating in the Battle of Hastings. The two main protagonists are Harold Godwinson, recently crowned King of England, leading the Anglo-Saxon English, and William, Duke of Normandy, leading a mainly Norman army, sometimes called the companions of William the Conqueror. Construction, design and technique: The Bayeux tapestry is embroidered in wool yarn on a tabby-woven linen ground 68.38 metres long and 0.5 metres wide (224.3 ft × 1.6 ft) and using two methods of stitching: outline or stem stitch for lettering and the outlines of figures, and couching or laid work for filling in figures. -

The Dictionary of Needlework

LIBRARY ^fsSSACHc,,^^ 1895 .1-^ Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from Boston Library Consortium IVIember Libraries sJlttp://^yyw.archive.org/details/dictionaryofneed01caul <^ ' jii'P-^^'^'^^'' THE DICTIONARY OF NEEDLEWORK. GERMAN CROSS STITCH PATTERN. RUSSIAN CROSS STITCH PATTERN. ITALIAN CROSS STITCH PATTERN. DEDICATED TO H.R.H. PRINCESS LOUISE, MARCHIONESS OF LORNE. THE ENCYCLOPEDIA OE ARTISTIC, PLAIN, AND EANCY NEEDLEWORK, DEALING FULLY WITH THE DETAILS OP ALL THE STITCHES EMPLOYED, THE METHOD OP WORKING, THE MATERIALS USED, THE MEANING OF TECHNICAL TERMS, AND, WHERE NECESSARY, TRACING THE ORIGIN AND HISTORY OP THE VARIOUS WORKS DESCRIBED. ILLUSTRATED WITH UPWARDS OF 1200 WOOD ENGRAVINGS, AND COLOURED PLATES. PLAIN SEWING, TEXTILES, DRESSMAKING, APPLIANCES, AND TERMS, By S. E. a. CAULEEILD, Author of "Side Nursing at Home," ^*Dc6Hiond," "Avcncle," and Faper6- on Needlework in ^'Thc Queen" "Girl's Omi Paper,' "Cassell's Domestic Dictionary" tOc. CHURCH EMBKOIDERY, LACE, AND ORNAMENTAL NEEDLEWORK, By BLANCHE C. SAWARD, Author of "Church Festival Decoration-'^" and Papers on Fa/ncy and Art Work in "The Bazaar," "Artistic Amusements," "Girl's Own Paper,'^ <Cr. SECOND EDITION. LONDON: A. W. COWAN, 30 AND 31, NEW BRIDGE STREET, LUDGATE CIRCUS. LONDON : PBINTED BY A. BRADLEY. 170, STRAND. ^^.c^^yj- C7 TO HER EOTAL HIGHNESS THE PRINCESS LOUISE, MARCHIONESS OE LORNE, THIS BOOK IS, BY HER SPECIAL PERMISSION, DEDICATED, In Acknowledgment of the Great Services which, by Means of Hee Cultivated Taste and Cordial Patronage, She has Rendered to the Arts of Plain Sewing and Embroidery. PREFACE TO FIRST EDITIOI. JOHN TAYLOR, in Queen Elizabeth's time, wrote a poem entirely in praise of Needlework; we, in a less romantic age, do not publish a poem, but a Dictionary, not in praise, but in practice, of the Art. -

The Humble Couching Stitch Research Paper Submitted by Natalie Dupuis April, 2020

The Humble Couching Stitch Research Paper Submitted by Natalie Dupuis www.SewByHand.com April, 2020 Subject: The humbly magnificent couching stitch from medieval times to present day, classified into distinct categories. INTRODUCTION Goldwork - one of the most beautiful techniques in hand embroidery - employs the humblest of stitches, the couching stitch. A stitch that theoretically is easily executed, but requires a steady hand and keen eye to be enjoyed at its highest precision. This paper provides a concise examination of the couching stitch as used in Europe from medieval times to present day. The various forms of couching stitches are reviewed with photographic support of both historic and modern examples. By the end of this paper it is the author’s wish that the reader will better understand the sub-categories of underside couching, pattern couching, diaper patterns, or nué, Italian shading, damascening, vermicelli, and contemporary variations. The couching stitch has been used for centuries to hold metal threads onto the surface of fabric. It’s most basic use can be traced back to extant samples from the 1st century BC in the Scythian community (Clabburn, 1976). Tortora & Phyllis (2007) define it as “a method of embroidering in which a design is made by various threads or cords laid upon the surface of a material and secured by fine stitches drawn through the material and across the cord.” Generally speaking, a single or double length of metal thread is laid upon the surface of the fabric, and is then held in place with a series of stitches which can be near invisible or highly visible, and regularly or irregularly spaced.