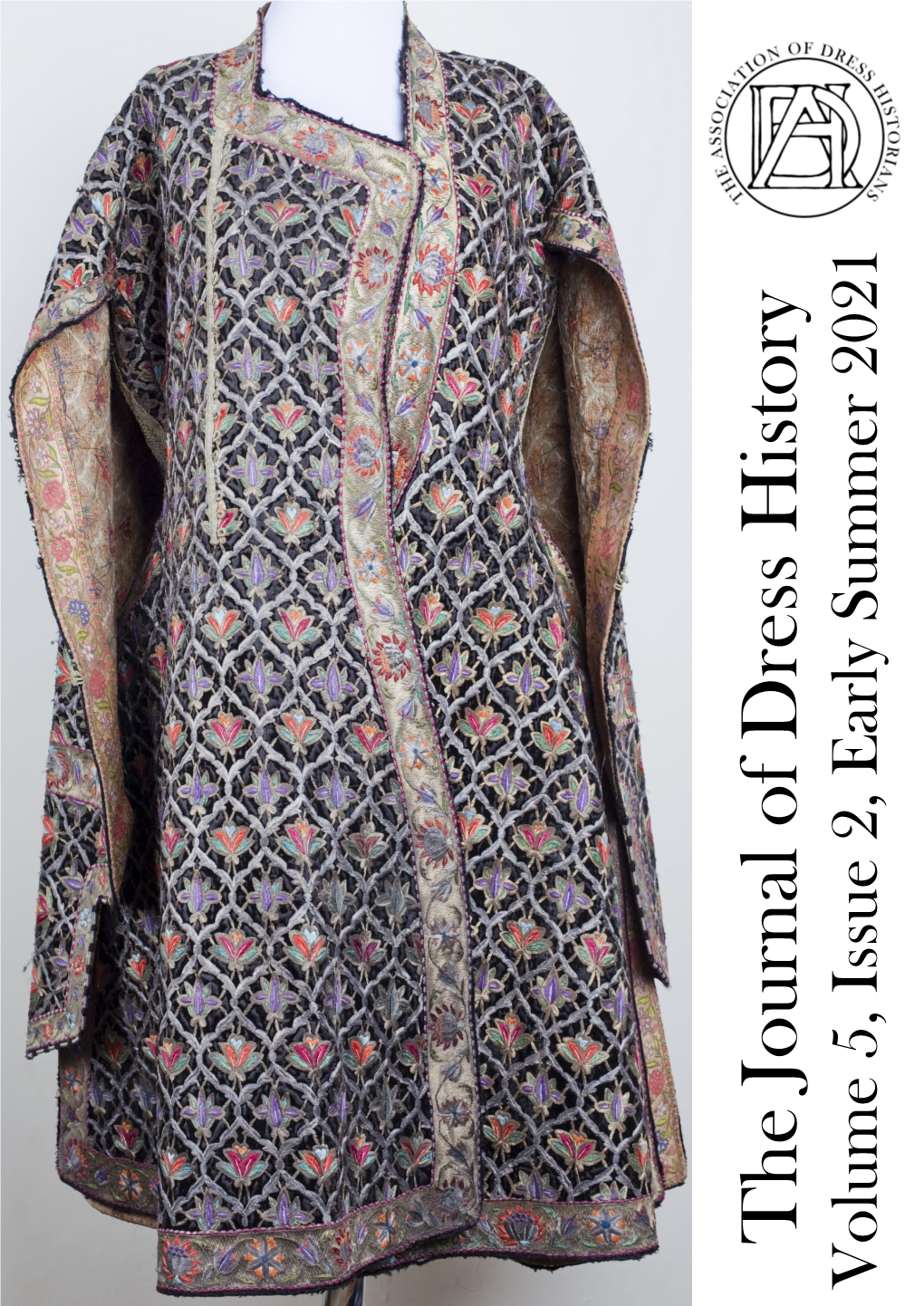

Volume 5, Issue 2, E Arly Summer 2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Textiles of the Han Dynasty & Their Relationship with Society

The Textiles of the Han Dynasty & Their Relationship with Society Heather Langford Theses submitted for the degree of Master of Arts Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Centre of Asian Studies University of Adelaide May 2009 ii Dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the research requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Centre of Asian Studies School of Humanities and Social Sciences Adelaide University 2009 iii Table of Contents 1. Introduction.........................................................................................1 1.1. Literature Review..............................................................................13 1.2. Chapter summary ..............................................................................17 1.3. Conclusion ........................................................................................19 2. Background .......................................................................................20 2.1. Pre Han History.................................................................................20 2.2. Qin Dynasty ......................................................................................24 2.3. The Han Dynasty...............................................................................25 2.3.1. Trade with the West............................................................................. 30 2.4. Conclusion ........................................................................................32 3. Textiles and Technology....................................................................33 -

Youtube and the Vernacular Rhetorics of Web 2.0

i REMEDIATING DEMOCRACY: YOUTUBE AND THE VERNACULAR RHETORICS OF WEB 2.0 Erin Dietel-McLaughlin A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2010 Committee: Kristine Blair, Advisor Louisa Ha Graduate Faculty Representative Michael Butterworth Lee Nickoson ii ABSTRACT Kristine Blair, Advisor This dissertation examines the extent to which composing practices and rhetorical strategies common to ―Web 2.0‖ arenas may reinvigorate democracy. The project examines several digital composing practices as examples of what Gerard Hauser (1999) and others have dubbed ―vernacular rhetoric,‖ or common modes of communication that may resist or challenge more institutionalized forms of discourse. Using a cultural studies approach, this dissertation focuses on the popular video-sharing site, YouTube, and attempts to theorize several vernacular composing practices. First, this dissertation discusses the rhetorical trope of irreverence, with particular attention to the ways in which irreverent strategies such as new media parody transcend more traditional modes of public discourse. Second, this dissertation discusses three approaches to video remix (collection, Detournement, and mashing) as political strategies facilitated by Web 2.0 technologies, with particular attention to the ways in which these strategies challenge the construct of authorship and the power relationships inherent in that construct. This dissertation then considers the extent to which sites like YouTube remediate traditional rhetorical modes by focusing on the genre of epideictic rhetoric and the ways in which sites like YouTube encourage epideictic practice. Finally, in light of what these discussions reveal in terms of rhetorical practice and democracy in Web 2.0 arenas, this dissertation offers a concluding discussion of what our ―Web 2.0 world‖ might mean for composition studies in terms of theory, practice, and the teaching of writing. -

All-Time Favorites

S W E A Jersey Cardigan Sweaters T E · Fabric: 100% pill-resistant acrylic R · Dyed-to-match buttons S · Reinforced stress areas All-time favorites · Elasticized rib-trim cuffs and bottom for shape retention 5912 Soft sweaters with staying power · Machine wash and dry 1970 Jersey Crewneck Cardigan (Female) · Full button-down front · No pockets Colors: Black, Brown, Cardinal, Green, Grey Heather, Lipstick, Mayfair, Mulberry, Navy, Spruce Green, White, Wine 1970 Sizes: Youth XXSY-XLY, Adult SA-3XLA 6305 Jersey V-Neck Cardigan · 5 buttons · No pockets 6305 Color: Navy Sizes: Youth XXSY-XLY, Adult SA-3XLA 5912 Two-Pocket Jersey V-Neck Cardigan · 5 buttons · Hemmed bottom Colors: Black, Brown, Cardinal, Charcoal Heather, Green, Grey Heather, Khaki, 5910 Lipstick, Mayfair, Mulberry, Nally Powder Blue, Navy, Purple, Spruce Green, White, Wine, Yellow Sizes: Youth XXSY-XLY, Adult SA-3XLA 5910 Jersey V-Neck Cardigan Vest · 4 buttons · No pockets Color: Navy Sizes: Youth XXSY-XLY, Adult SA-3XLA Our cozy sweaters and vests offer timeless styling and a consistent, dependable fit. Made from wear-tested yarns, Schoolbelles sweaters are Black Brown Cardinal both wonderfully soft and incredibly durable. They pair perfectly with Charcoal Green Grey Heather our polos or button-up shirts. For extra identity, add your school logo. Heather Khaki Lipstick Mayfair Nally Mulberry Navy Powder Blue Purple Spruce Green White Wine Yellow 6 7 schoolbelles.com | 1-888-637-3037 Schoolbelles School Uniforms S Jersey Pullover Sweaters W E 1995 Jersey Crewneck Long-Sleeve -

Helzapoppin' Prca Rodeo March 22,2009 3Rd

HELZAPOPPIN’ PRCA RODEO MARCH 22,2009 3RD PERFORMANCE SUNDAY MATINEE 2:00 PM OPENING CEREMONIES NATIONAL ANTHEM BAREBACK RIDING 1.112 Dalon Hulsey Luna, NM 365 vegas lites 2. 42 Todd Burns Albuquerque, NM R13 3.126 Chauncey Kirby Ft. McDowell, AZ N05 Ghost Light 4.217 Forrie Smith Capitan, NM D0 Fog lite 5. 68 Luis Escudero vado, NM 305 Storm Warning 6. 99 Stetson Herrera Albuquerque, NM 86 Standing Tall Reride: L Dunny INTRODUCTIONS OF COMMITTEE & QUEENS STEER WRESTLING 192 Tim Robertson Oro Valley, AZ 242 Clayton Tuchscherer Cortaro, AZ 176 Cutter Parsons Marana, AZ 214 Justin Simon Florence, AZ 78 Denny Garcia Peoria, AZ 13 Pepe Arballo Wittman, AZ 63 Trevor Duhon Phoenix, AZ 59 Matt Deskovick Ramona, CA 34 Stan Branco Chowchilla, CA 246 Jack Vanderlans Temecula, CA 75 Jeff Frizzell Marana, AZ CLOWNIN' AROUND WITH SLIM SADDLE BRONC RIDING 1.152 Lance Miller Panguitch, UT CJ Cracker Jack 2.257 Quint Westcott Flora Vista, NM -W Millenium 3. 6 Jason Amon Payson, AZ -1 Roan Hawk 4. 33 Olan Borg Las Cruces, NM L0 Cracklin Fog 5. 64 Thor Dusenberry Desert Hills, AZ C12 Fantasia 6. 57 Bart Davis Suprise, AZ 011 Never Cry 7. 7 Kendall Anderson Grantsville, UT -2 Slippery 8. 94 Jay Harrison Aztec, NM G9 Sock Puppet 9.273 Dan Yeager Aztec, NM N8 Cracked Ice Reride: -31 DRILL TEAM - ESCARMUZA CHARRA TONALI TIE DOWN ROPING 146 Wesley McConnel Bloomfield, NM 199 Tyson Runyan Radium Springs, NM 65 Kyle Dutton Las Cruces, NM 48 Paul Carmen Buckeye, AZ 246 Jack Vanderlans Temecula, CA 106 Seth Hopper Stanfield, OR 221 Bill Snure Benson, AZ 123 J.D. -

The Morgue File 2010

the morgue file 2010 DONE BY: ASSIL DIAB 1850 1900 1850 to 1900 was known as the Victorian Era. Early 1850 bodices had a Basque opening over a che- misette, the bodice continued to be very close fitting, the waist sharp and the shoulder less slanted, during the 1850s to 1866. During the 1850s the dresses were cut without a waist seam and during the 1860s the round waist was raised to some extent. The decade of the 1870s is one of the most intricate era of women’s fashion. The style of the early 1870s relied on the renewal of the polonaise, strained on the back, gath- ered and puffed up into an detailed arrangement at the rear, above a sustaining bustle, to somewhat broaden at the wrist. The underskirt, trimmed with pleated fragments, inserting ribbon bands. An abundance of puffs, borders, rib- bons, drapes, and an outlandish mixture of fabric and colors besieged the past proposal for minimalism and looseness. women’s daywear Victorian women received their first corset at the age of 3. A typical Victorian Silhouette consisted of a two piece dress with bodice & skirt, a high neckline, armholes cut under high arm, full sleeves, small waist (17 inch waist), full skirt with petticoats and crinoline, and a floor length skirt. 1894/1896 Walking Suit the essential “tailor suit” for the active and energetic Victorian woman, The jacket and bodice are one piece, but provide the look of two separate pieces. 1859 zouave jacket Zouave jacket is a collarless, waist length braid trimmed bolero style jacket with three quarter length sleeves. -

Canadian Eventing Team 2008 Media Guide

Canadian Eventing Team 2008 Media Guide The Canadian Eventing High Performance Committee extends sincere thanks and gratitude to the Sponsors, Supporters, Suppliers, Owners and Friends of the Canadian Eventing Team competing at the Olympic Games in Hong Kong, China, August 2008. Sponsors, Supporters & Friends Bahr’s Saddlery Mrs. Grit High Mr. & Mrs. Jorge Bernhard Mr. & Mrs. Ali & Nick Holmes-Smith Canadian Olympic Committee Mr. & Mrs. Alan Law Canadian Eventing members Mr. Kenneth Rose Mr. & Mrs. Elaine & Michael Davies Mr. & Mrs. John Rumble Freedom International Brokerage Company Meredyth South Sport Canada Starting Gate Communications Eventing Canada (!) Cealy Tetley Photography Overlook Farm Mr. Graeme Thom The Ewen B. “Pip” Graham Family Anthony Trollope Photography Mr. James Hewitt Mr. & Mrs. Anne & John Welch Ð Ñ Official Suppliers Bayer Health Care Supplier of Legend® to the Canadian Team horses competing at the Olympic Games Baxter Corporation and BorderLink Veterinary Supplies Inc Supplier of equine fluid support products to the Canadian Team horses competing at the Olympic Games Cedar Peaks Ent. Supplier of Boogaloo Brushing Boots for the Canadian Team horses competing at the Olympic Games Flair LLC Supplier of Flair Nasal Strips to the Canadian Team horses competing at the Olympic Games Freedom Heath LLC Supplier of SUCCEED® to the Canadian Team horses competing at the Olympic Games GPA Sport Supplier of the helmets worn by the Canadian Team riders Horseware Ireland Supplier of horse apparel to the Canadian Team horses competing at the Olympic Games Phoenix Performance Products Supplier of the Tipperay 1015 Eventing Vest worn by the Canadian Team riders Merial Canada Canada Inc. -

Ethical Fashion Catalogue Content Brand 2 Collection 4 Index 12 Clothing 14 Essentials 72 Artist 76 Overview 158

ACCESSORIES | Spring Summer 2019 ETHICAL FASHION CATALOGUE CONTENT BRAND 2 COLLECTION 4 INDEX 12 CLOTHING 14 ESSENTIALS 72 ARTIST 76 OVERVIEW 158 DELIVERY DROPS DROP 1 Delivery from 10th to 31st of JANUARY. DROP 2 Delivery from 1st to 28th of FEBRUARY. DROP 3 Delivery from 1st to 31st of MARCH. THE SKFK WAY Dress how you are, how you feel, how you live. Strengthen your identity, express your essence and take care of your environment. Connect with nature and accessorize with its shapes and colors. A casual and minimal collection, functional and 100% cruelty free. 4 5 6 7 86% OF THIS ACCESSORIES GLOBAL APPROACH COLLECTION WAS CREATED USING COTTON PAPER The cotton left in the soil is the perfect ENVIRONMENTALLY PREFERRED non polluting alternative we love! Our hangtags and stationary are made from it. FIBERS AND IS 100% CRUELTY FREE. ECO PACKAGING We use bioplastic bags, recycled paper MATERIALS: and forest respectful paper. CARBON FOOTPRINT We use sea freight to transport our goods and our headquarters and our shops are 100% powered by renewable energy, certified by Goiener. Download our app and find how much CO2 our garments emit: RECYCLED POLYESTER ORGANIC COTTON impact.skunkfunk.com. Plastic bottles turned into No pesticides, fertilizers or fabric. Fabric transformed genetically modified seeds. into awesome clothes. Purest fiber ever, no kidding. CERTIFIED COMMITMENT Fairtrade means better “Organic” and “made with conditions and opportunities for organic” certified by Ecocert cotton producers in developing Greenlife F32600, license countries to invest in their number: 127906 SKUNKFUNK. RECYCLED COTTON RECYCLED NYLON businesses and communities for A fiber made from cut-offs Ocean waste with a new life. -

The Sari Ebook

THE SARI PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Mukulika Banerjee | 288 pages | 16 Sep 2008 | Bloomsbury Publishing PLC | 9781847883148 | English | London, United Kingdom The Sari PDF Book Anushka Sharma. So shop for yourself or gift a sari to someone, we have something for everyone. The wavy bun completed her look. Face Deal. Long-time weaving families have found themselves out of work , their looms worthless. Sari , also spelled saree , principal outer garment of women of the Indian subcontinent, consisting of a piece of often brightly coloured, frequently embroidered, silk , cotton , or, in recent years, synthetic cloth five to seven yards long. But for some in Asian American communities, the prospect of the nation's first Black and South Asian Vice President wearing a traditional sari at any of the inauguration events -- even if the celebrations are largely virtual -- has offered a glimmer of positivity amid the tumult. Zari Work. As a politician, Dimple Kapadia's sarees were definitely in tune with the sensibilities but she made a point of draping elegant and minimal saree. Batik Sarees. Party Wear. Pandadi Saree. While she draped handloom sarees in the series, she redefined a politician's look with meticulous fashion sensibility. Test your visual vocabulary with our question challenge! Vintage Sarees. Hence there are the tie-dye Bandhani sarees, Chanderi cotton sarees and the numerous silk saree varieties including the Kanchipuram, Banarasi and Mysore sarees. You can even apply the filter as per the need and choose whatever fulfil your requirements in the best way. Yes No. Valam Prints. Green woven cotton silk saree. Though it's just speculation at this stage, and it's uncertain whether the traditional ball will even go ahead, Harris has already demonstrated a willingness to use her platform to make sartorial statements. -

Of 8 SQUIRE BOONE VILLAGE Price 2 BR156D-IR BROWN DIAMOND

SQUIRE BOONE VILLAGE 08/30/21 Cat Qty SALES Whls Page# Item # Item Name Available UOM Price Price 2 BR156D-IR BROWN DIAMOND GOLDSTONE, TUMBLED, ASSORTED SIZES 244 LB 6.20 3.10 2 BR145TS-2 MAGNET STONES, TITANIUM SILVER, SECOND QUALITY 1,629 LB 6.25 3.13 2 BR145TG-2 MAGNET STONES, TITANIUM GOLD, SECOND QUALITY 2,057 LB 6.25 3.13 3 RE121-IR REPLICA FOSSIL SEAL TOOTH 2,200 EA 0.75 0.38 3 RE117-IR PREHISTORIC FOSSIL BEAR FANG, REPLICA 1,985 EA 0.80 0.40 3 RE118-IR PREHISTORIC FOSSIL SHORT FACED BEAR FANG, REPLICA 1,597 EA 0.95 0.48 3 KC302-IR SEA HORSE KEY RING, REPLICA 307 EA 1.30 0.65 3 RE109-2 FOSSIL REPLICA, RAPTOR CLAW, SECOND QUALITY 9,900 PK25 20.00 10.00 3 RE300S-IR CARVED SEAL HEAD DISPLAY 38 EA 28.00 14.00 3 BR500ML-IR LARGE MOON ROCK “BY THE BAGFUL” DISPLAY 8 EA 250.00 125.00 4 SE112-IR TURBO SEASHELLS 35 LB5 11.75 5.88 4 SE113-IR CANARIUM SEASHELL 17 LB5 11.75 5.88 4 SE114-IR CONOMUREX SEASHELL 356 LB5 11.75 5.88 4 SE119-IR AURISDIANAL SEASHELLS 23 LB5 11.75 5.88 4 SE122-IR COLOR ENHANCED TURBO SEASHELLS 776 LB5 17.00 8.50 4 SE123-IR COLOR ENHANCED COCKLE SEASHELLS 295 LB5 17.00 8.50 4 SE125-IR COLOR ENHANCED TRITON SEASHELLS 524 LB5 17.00 8.50 5 SA602-IR ANDEAN STONE, FLYING EAGLE, SMALL 51 EA 1.35 0.68 5 SA612-IR ANDEAN STONE, ALLIGATOR, SMALL 110 EA 1.35 0.68 5 LU103-IR KEY CHAIN, 6 SIDED ETCHED CLOVER 64 EA 1.60 0.80 5 OX108D-IR ONYX, FRUIT, MINI, ASSORTED., 10ct BAG 831 PK10 4.20 2.10 5 TL136-IR MARBLE SQUARE TALL TEA LIGHT HOLDER 5 EA 5.80 2.90 5 R6017-IR SATIN SPAR SELENITE ANGEL, 3 3/4" TALL 68 EA 13.40 6.70 5 TL205-IR -

Object Summary Collections 11/19/2019 Collection·Contains Text·"Manuscripts"·Or Collection·Contains Text·"University"·And Status·Does Not Contain Text·"Deaccessioned"

Object_Summary_Collections 11/19/2019 Collection·Contains text·"Manuscripts"·or Collection·Contains text·"University"·and Status·Does not contain text·"Deaccessioned" Collection University Archives Artifact Collection Image (picture) Object ID 1993-002 Object Name Fan, Hand Description Fan with bamboo frame with paper fan picture of flowers and butterflies. With Chinese writing, bamboo stand is black with two legs. Collection University Archives Artifact Collection Image (picture) Object ID 1993-109.001 Object Name Plaque Description Metal plaque screwed on to wood. Plaque with screws in corner and engraved lettering. Inscription: Dr. F. K. Ramsey, Favorite professor, V. M. Class of 1952. Collection University Archives Artifact Collection Image (picture) Object ID 1993-109.002 Object Name Award Description Gold-colored, metal plaque, screwed on "walnut" wood; lettering on brown background. Inscription: Present with Christian love to Frank K. Ramsey in recognition of his leadership in the CUMC/WF resotration fund drive, June 17, 1984. Collection University Archives Artifact Collection Image (picture) Object ID 1993-109.003 Object Name Plaque Description Wood with metal plaque adhered to it; plque is silver and black, scroll with graphic design and lettering. Inscription: To Frank K. Ramsey, D. V. M. in appreciation for unerring dedication to teaching excellence and continuing support of the profession. Class of 1952. Page 1 Collection University Archives Artifact Collection Image (picture) Object ID 1993-109.004 Object Name Award Description Metal plaque screwed into wood; plaque is in scroll shape on top and bottom. Inscription: 1974; Veterinary Service Award, F. K. Ramsey, Iowa Veterinary Medical Association. Collection University Archives Artifact Collection Image (picture) Object ID 1993-109.005 Object Name Award Description Metal plaque screwed onto wood; raised metal spray of leaves on lower corner; black lettering. -

A Plantation Family Wardrobe, 1825 - 1835

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2010 A Plantation Family Wardrobe, 1825 - 1835 Jennifer Lappas Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/2299 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 The Carter Family Shirley Plantation claims the rightful spot as Virginia’s first plantation and the oldest family-run business in North America. It began as a royal land grant given to Sir Thomas West and his wife Lady Cessalye Shirley in 1613 and developed into the existing estate one can currently visit by 1725. The present day estate consists of the mansion itself and ten additional buildings set along a Queen Anne forecourt. These buildings include a Root Cellar, Pump House, two-story Plantation Kitchen, two story Laundry, Smokehouse, Storehouse with an Ice House below, a second Storehouse for grain, Brick Stable, Log Barn and Pigeon House or Dovecote. At one time the Great House was augmented by a North and a South Flanker: they were two free standing wings, 60 feet long and 24 feet wide and provided accommodations for visitors and guests. The North Flanker burned and its barrel-vaulted basement was converted into a root cellar and the South Flanker was torn down in 1868. -

Fashion,Costume,And Culture

FCC_TP_V4_930 3/5/04 3:59 PM Page 1 Fashion, Costume, and Culture Clothing, Headwear, Body Decorations, and Footwear through the Ages FCC_TP_V4_930 3/5/04 3:59 PM Page 3 Fashion, Costume, and Culture Clothing, Headwear, Body Decorations, and Footwear through the Ages Volume 4: Modern World Part I: 19004 – 1945 SARA PENDERGAST AND TOM PENDERGAST SARAH HERMSEN, Project Editor Fashion, Costume, and Culture: Clothing, Headwear, Body Decorations, and Footwear through the Ages Sara Pendergast and Tom Pendergast Project Editor Imaging and Multimedia Composition Sarah Hermsen Dean Dauphinais, Dave Oblender Evi Seoud Editorial Product Design Manufacturing Lawrence W. Baker Kate Scheible Rita Wimberley Permissions Shalice Shah-Caldwell, Ann Taylor ©2004 by U•X•L. U•X•L is an imprint of For permission to use material from Picture Archive/CORBIS, the Library of The Gale Group, Inc., a division of this product, submit your request via Congress, AP/Wide World Photos; large Thomson Learning, Inc. the Web at http://www.gale-edit.com/ photo, Public Domain. Volume 4, from permissions, or you may download our top to bottom, © Austrian Archives/ U•X•L® is a registered trademark used Permissions Request form and submit CORBIS, AP/Wide World Photos, © Kelly herein under license. Thomson your request by fax or mail to: A. Quin; large photo, AP/Wide World Learning™ is a trademark used herein Permissions Department Photos. Volume 5, from top to bottom, under license. The Gale Group, Inc. Susan D. Rock, AP/Wide World Photos, 27500 Drake Rd. © Ken Settle; large photo, AP/Wide For more information, contact: Farmington Hills, MI 48331-3535 World Photos.