Bickers, RA. (2014). Moving Stories: Memorialisation and Its Legacies in Treaty Port China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

February, 1955

Library of The Harvard Musical Association Bulletin No. 23 February, 1955 Library Committee CHARLES R. NUTTER JOHN N. BURK RICHARD G. APPEL CYRUS DURGIN RUDOLPH ELIE Director of the Library and Library and Custodian of the Marsh Room Marsh Room Marsh Room CHARLES R. NUTTER MURIEL FRENCH FLORENCE C. ALLEN To the Members of the Association: Your attention is called to an article in this issue by Albert C. Koch. * * * * REPORT ON THE LIBRARY AND ON THE MARSH ROOM FOR THE YEAR 1954 To the President and the Directors of The Harvard Musical Association: Today, when television and the radio, both A.M. and F.M., are providing much of the intellectual sustenance for the common man and woman, the individual who turns for an intellectual repast to the writers of past centuries and also tries to phrase his thoughts both vocal and written with some regard to the rules of grammar and the principles of rhetoric is regarded as high‐brow and is thrown out of society. I am aware that I lay myself open to the charge of being a high‐brow, a charge that creates no reactionary emotion at all, especially as it comes usually from the low‐brow, and that I may be thrown out of society into a lower stratum, when I state that for the text of this report I have turned to a gentleman whose mortal life spanned the years between 1672 and 1719. Even the low‐brow has probably heard or read the name Joseph Addison, though it may convey nothing to him except the fact that it has an English and not a foreign sound. -

New Editions 2012

January – February 2013 Volume 2, Number 5 New Editions 2012: Reviews and Listings of Important Prints and Editions from Around the World • New Section: <100 Faye Hirsch on Nicole Eisenman • Wade Guyton OS at the Whitney • Zarina: Paper Like Skin • Superstorm Sandy • News History. Analysis. Criticism. Reviews. News. Art in Print. In print and online. www.artinprint.org Subscribe to Art in Print. January – February 2013 In This Issue Volume 2, Number 5 Editor-in-Chief Susan Tallman 2 Susan Tallman On Visibility Associate Publisher New Editions 2012 Index 3 Julie Bernatz Managing Editor Faye Hirsch 4 Annkathrin Murray Nicole Eisenman’s Year of Printing Prodigiously Associate Editor Amelia Ishmael New Editions 2012 Reviews A–Z 10 Design Director <100 42 Skip Langer Design Associate Exhibition Reviews Raymond Hayen Charles Schultz 44 Wade Guyton OS M. Brian Tichenor & Raun Thorp 46 Zarina: Paper Like Skin New Editions Listings 48 News of the Print World 58 Superstorm Sandy 62 Contributors 68 Membership Subscription Form 70 Cover Image: Rirkrit Tiravanija, I Am Busy (2012), 100% cotton towel. Published by WOW (Works on Whatever), New York, NY. Photo: James Ewing, courtesy Art Production Fund. This page: Barbara Takenaga, detail of Day for Night, State I (2012), aquatint, sugar lift, spit bite and white ground with hand coloring by the artist. Printed and published by Wingate Studio, Hinsdale, NH. Art in Print 3500 N. Lake Shore Drive Suite 10A Chicago, IL 60657-1927 www.artinprint.org [email protected] No part of this periodical may be published without the written consent of the publisher. -

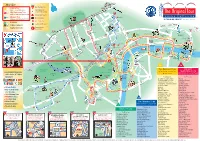

A4 Web Map 26-1-12:Layout 1

King’s Cross Start St Pancras MAP KEY Eurostar Main Starting Point Euston Original Tour 1 St Pancras T1 English commentary/live guides Interchange Point City Sightseeing Tour (colour denotes route) Start T2 W o Language commentaries plus Kids Club REGENT’S PARK Euston Rd b 3 u Underground Station r n P Madame Tussauds l Museum Tour Russell Sq TM T4 Main Line Station Gower St Language commentaries plus Kids Club q l S “A TOUR DE FORCE!” The Times, London To t el ★ River Cruise Piers ss Gt Portland St tenham Ct Rd Ru Baker St T3 Loop Line Gt Portland St B S s e o Liverpool St Location of Attraction Marylebone Rd P re M d u ark C o fo t Telecom n r h Stansted Station Connector t d a T5 Portla a m Museum Tower g P Express u l p of London e to S Aldgate East Original London t n e nd Pl t Capital Connector R London Wall ga T6 t o Holborn s Visitor Centre S w p i o Aldgate Marylebone High St British h Ho t l is und S Museum el Bank of sdi igh s B tch H Gloucester Pl s England te Baker St u ga Marylebone Broadcasting House R St Holborn ld d t ford A R a Ox e re New K n i Royal Courts St Paul’s Cathedral n o G g of Justice b Mansion House Swiss RE Tower s e w l Tottenham (The Gherkin) y a Court Rd M r y a Lud gat i St St e H n M d t ill r e o xfo Fle Fenchurch St Monument r ld O i C e O C an n s Jam h on St Tower Hill t h Blackfriars S a r d es St i e Oxford Circus n Aldwyc Temple l a s Edgware Rd Tower Hil g r n Reg Paddington P d ve s St The Monument me G A ha per T y Covent Garden Start x St ent Up r e d t r Hamleys u C en s fo N km Norfolk -

City Research Online

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Summerfield, Angela (2007). Interventions : Twentieth-century art collection schemes and their impact on local authority art gallery and museum collections of twentieth- century British art in Britain. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City University, London) This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/17420/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] 'INTERVENTIONS: TWENTIETH-CENTURY ART COLLECTION SCIIEMES AND TIIEIR IMPACT ON LOCAL AUTHORITY ART GALLERY AND MUSEUM COLLECTIONS OF TWENTIETII-CENTURY BRITISH ART IN BRITAIN VOLUME If Angela Summerfield Ph.D. Thesis in Museum and Gallery Management Department of Cultural Policy and Management, City University, London, August 2007 Copyright: Angela Summerfield, 2007 CONTENTS VOLUME I ABSTRA.CT.................................................................................. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS •........••.••....••........•.•.•....•••.......•....•...• xi CHAPTER 1:INTRODUCTION................................................. 1 SECTION 1 THE NATURE AND PURPOSE OF PUBLIC ART GALLERIES, MUSEUMS AND THEIR ART COLLECTIONS.......................................................................... -

HARRY SMITH PARKES, the FIRST BRITISH GO PLAYER in JAPAN Guoru Ding and Franco Pratesi [email protected] [email protected]

HARRY SMITH PARKES, THE FIRST BRITISH GO PLAYER IN JAPAN Guoru Ding and Franco Pratesi [email protected] [email protected] In his book “Goh or Wei chi” of 1911, with just casual visits of players from the first complete treatment of Go Asia. It seems likely that a group in Great Britain, Horace Cheshire of native players had formed, with mentioned that he had played the the occasional assistance of stronger game of Go for some thirty years and players from China and/or Japan. that his sources were both Chinese Unfortunately, it is very difficult to and Japanese. Possibly people he had find any evidence for it. played with were students or scholars from China or Japan. For instance, in Therefore it is Oskar Korschelt 1877, there was a group of Chinese who deserves the credit for having students that came to study at the introduced the game into Europe. Royal Navy College at Greenwich. His articles (then collected in a book, They stayed for several years; some which did not have a large circulation only 2-3 years, and some for 5-6 years. and soon became rare) were enough They had had formal traditional to teach the essential technique of Chinese training and had acquired the game. Richard Schurig, an expert some Western naval knowledge; after chess player and writer, published a finishing their training in England, booklet on its basis in 1882, in Leipzig, they became the first generation of which was considered (first of all by Chinese Navy officials. They were its author) as easier to understand and to use as a handbook for beginners; roughly the same age as Cheshire, and a confirmation can be found in the some of them played weiqi. -

Revival After the Great War Rebuild, Remember, Repair, Reform

Revival after the Great War Rebuild, Remember, Repair, Reform Edited by Luc Verpoest, Leen Engelen, Rajesh Heynickx, Jan Schmidt, Pieter Uyttenhove, and Pieter Verstraete LEUVEN UNIVERSITY PRESS Published with the support of the KU Leuven Fund for Fair Open Access, the City of Leuven and LUCA School of Arts Published in 2020 by Leuven University Press / Presses Universitaires de Louvain / Universitaire Pers Leuven. Minderbroedersstraat 4, B-3000 Leuven (Belgium). © 2020 Selection and editorial matter: Luc Verpoest, Leen Engelen, Rajesh Heynickx, Jan Schmidt, Pieter Uyttenhove, and Pieter Verstraete © 2020 Individual chapters: The respective authors This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial Non- Derivative 4.0 International Licence. The license allows you to share, copy, distribute, and transmit the work for personal and non-commercial use providing author and publisher attribution is clearly stated. Attribution should include the following information: Luc Verpoest, Leen Engelen, Rajesh Heynickx, Jan Schmidt, Pieter Uyttenhove, and Pieter Verstraete (eds.). Revival after the Great War: Rebuild, Remember, Repair, Reform. Leuven, Leuven University Press. (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) Further details about Creative Commons licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ ISBN 978 94 6270 250 9 (Paperback) ISBN 978 94 6166 354 2 (ePDF) ISBN 978 94 6166 355 9 (ePUB) https://doi.org/10.11116/9789461663542 D/2020/1869/60 NUR: 648 Layout: Friedemann Vervoort Cover design: Anton Lecock Cover illustration: A family -

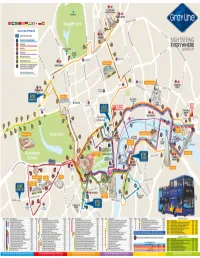

New HOHO Map.Jpg

Hop-on Hop-off timetable from 5th 2019 Mondays to Fridays Saturdays, Sundays except Public Holidays & Public Holidays STOP Route Stop and Attractions First Last Last First Last Last No. Bus Loop Bus Bus Loop Bus 1 Victoria, Buckingham Palace Road, Stop 8. 09:00 17:00 22:02 09:00 17:00 22:02 GTVC, Victoria Coach Station, Victoria Place, Shops and Restaurants 2 Buckingham Gate, Tourist bus stop. 08:05 17:11 18:37 08:05 17:11 18:3 Buckingham Palace, Queen's Gallery and Royal Mews. 3 Parliament Street, stop C, HM Treasury.. 09:0 18:0 :8 09:0 18:0 :8 Parliament Square, Downing Street and The Cenotaph. 4 Whitehall, Tourist stop, Horse Guards Parade. 09:5 18:5 :3 09: 18:5 :3 Horse Guards, Banqueting House and Trafalgar Square. 5 Piccadilly Circus, Piccadilly, bus stop S 10:8 1:8 :8 10:8 1:8 :8 Piccadilly Circus, Eros, Trocadero and Soho. 6 Piccadilly, Tourist stop, Green Park Station. 0:1 1: :5 0:2 1:3 :3 Green Park, The Ritz and Buckingham Palace. 7 Piccadilly, Tourist stop, at Hyde Park Corner. 1: : 0:5 : 1:7 Bomber Command Memorial, Hard Pock Café and Mayfair. 8 Knightsbridge, Lanesborough Hotel. Stop 13. : 1: : : 1: : Hyde Park Corner, Wellington Museum and Wellington Arch. 9 Knightsbridge, At Scotch House, Stop KE. :7 1:7 :8 : : : Harrods 10 Kensington Gore, Royal Albert Hall, Stop K3. 1: 17: 2: 1: 17: : Royal Albert Hall and Albert Memorial. 11 Kensington Road, Palace Gate, bus stop no. 11150. -

200 2 Willow Road 157 10 Downing Street 35 Abbey Road Studios 118

200 index 2 Willow Road 157 Fifty-Five 136 10 Downing Street 35 Freedom Bar 73 Guanabara 73 A Icebar 112 Abbey Road Studios 118 KOKO 137 Accessoires 75, 91, 101, 113, 129, 138, Mandarin Bar 90 Ministry of Sound 63 147, 162 Oliver’s Jazz Bar 155 Admiralty Arch 29 Portobello Star 100 Aéroports Princess Louise 83 London Gatwick Airport 171 Proud Camden 137 London Heathrow Airport 170 Purl 120 Afternoon tea 110 Salt Whisky Bar 112 Albert Memorial 88 She Soho 73 Alimentation 84, 101, 147 Shochu Lounge 83 Ambassades de Kensington Palace Simmon’s 83 Gardens 98 The Commercial Tavern 146 Antiquités 162 The Craft Beer Co. 73 Apsley House 103 The Dublin Castle 137 ArcelorMittal Orbit 166 The George Inn 63 Argent 186 The Mayor of Scaredy Cat Town 147 Artisanat 162 The Underworld 137 Auberges de jeunesse 176 Up the Creek Comedy Club 155 Vagabond 84 B Battersea Park 127 Berwick Street 68 Bank of England Museum 44 Big Ben 36 Banques 186 Bloomsbury 76 Banqueting House 34 Bond Street 108 Barbican Centre 51 Boris Bikes 185 Bars et boîtes de nuit 187 Borough Market 61 Admiral Duncan 73 Boxpark 144 Bassoon 39 Brick Lane 142 Blue Bar 90 British Library 77 BrewDog 136 Bunga Bunga 129 British Museum 80 Callooh Callay 146 Buckingham Palace 29 Cargo 146 Bus à impériale 184 Churchill Arms 100 Duke of Hamilton 162 C fabric 51 Cadeaux 39, 121, 155 http://www.guidesulysse.com/catalogue/FicheProduit.aspx?isbn=9782765826774 201 Cadogan Hall 91 Guy Fawkes Night 197 Camden Market 135 London Fashion Week 194, 196 Camden Town 130 London Film Festival 196 Cenotaph, The 35 London Marathon 194 Centres commerciaux 51, 63 London Restaurant Festival 196 Charles Dickens Museum 81 New Year’s Day Parade 194 Cheesegrater 40 New Year’s Eve Fireworks 197 Chelsea 122 Notting Hill Carnival 196 Pearly Harvest Festival 196 Chelsea Flower Show 195 Six Nations Rugby Championship 194 Chelsea Physic Garden 126 St. -

The Iconography of O'connell Street and Environs After Independence

Symbolising the State— the iconography of O’Connell Street and environs after Independence (1922) Yvonne Whelan Academy for Irish Cultural Heritages, University of Ulster, Magee Campus Derry ABSTRACT This paper explores the iconography of Dublin’s central thoroughfare, O’Connell Street and its immediate environs in the decades following the establishment of the Irish Free State in 1922. It follows an earlier paper which examined the iconography of Sackville Street before Independence and turns the focus towards an analysis of the ways in which the street became a significant site for the cul- tural inscription of post-colonial national identity. It is argued that the erection of new monuments dedicated to the commemoration of the 1916 Rising, as well as the destruction of older imperial symbols, rendered visible the emergence of the newly independent Irish Free State. The paper charts this process of iconograph- ical inscription but also argues that O’Connell Street as a totality has taken on greater symbolic significance than any of the monuments that line its centre. In conclusion the paper examines the contemporary iconography of the street and addresses the apparent transition from political sculpture to public art which has taken place in recent decades throughout the city. Key index words: O’Connell Street, iconography, national identity, monuments. Introduction The great thoroughfare which the citizen of Dublin was accustomed to describe proudly “as the finest street in Europe” has been reduced to a smoking reproduction of the ruin wrought at Ypres by the mercilessness of the Hun. Elsewhere throughout the city streets have been devastated, centres of thriving industry have been placed in peril or ruined, a paralysis of work and commerce has been imposed, and the pub- lic confidence that is the life of trade and employment has received a staggering blow from which it will take almost a generation to recover” (The Freeman’s Journal, 26th April - 5th May 1916). -

The Birth of an Imperial Location: Comparative Perspectives on Western Colonialism in China

Leiden Journal of International Law (2018), page 1 of 28 C Foundation of the Leiden Journal of International Law 2018 doi:10.1017/S0922156518000274 INTERNATIONAL LEGAL THEORY The Birth of an Imperial Location: Comparative Perspectives on Western Colonialism in China ∗ LUIGI NUZZO Abstract The thematic horizon within which this article takes place is the colonial expansion of the Western powers in China between the nineteenth and the twentieth centuries. Focusing on the foundation of the British, French and American concessions in Tianjin, it aims to reconstruct the Western strategies of colonial governance and the role played by law in the process of productionofanewsocialspace.Openedasatreatyportin1860,TianjinistheonlyChinesecity where up to nine foreign concessions coexisted, becoming a complex, hybrid space (in)between EastandWest,definedbysocialpractices,symbolicrepresentations,andlegalcategories,which does not coincide simply with the area defined by the entity as a state, nation, or city. Keywords China (nineteenth century); colonial law; international law; Tianjin; Western imperialism 1. INTRODUCTION The history of Western concessions in the northeastern Chinese port of Tianjin began in 1860, when the Beijing Convention leased three large tracts of land in perpetuity to Britain, France and the United States, in return for a small ground rent paid annually to China.1 Concession rights were given also to Germany in 1895 and to Japan in 1896, but it was only at the beginning of the twentieth century with the defeat of the Boxer Rebellion and occupation by the allied army (the US, Britain, France, Japan, Russia, Germany, Austria-Hungary and Italy) that Tianjin changed definitively. In the 1901 BoxerProtocol,thealliedpowersgainedtherighttooccupy‘certainpointsinorderto ∗ Professor of Legal History and History of International Law, University of Salento (Lecce), Italy [[email protected]]. -

Presencingdigital Heritage Within Our Everyday Lives

DOI - http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/2237-266042979 ISSN 2237-2660 Time Trails: presencing digital heritage within our everyday lives Gabriella Giannachi William Barrett University of Exeter – Exeter, England Paul Farley Exeter City Football Club Supporters Trust – Exeter, England Andy Chapman 1010 Media – Exeter, England Thomas Cadbury Rick Lawrence Helen Burbage Royal Albert Memorial Museum and Art Gallery – RAMM, Exeter, England ABSTRACT – Time Trails: presencing digital heritage within our everyday lives1 – The Time Trails project is a collaboration between the Centre for Intermedia at the University of Exeter, Royal Albert Memorial Museum and Art Gallery, 1010 Media, and Exeter City Football Club Supporters Trust (2013). It is a mobile web app to allow users to follow, annotate and create trails using text, images and videos, and to respond to them via social media. Two trails narrating the history of Exeter City Football Club and its Supporters Trust, used for mobile learning and as part of sport and cultural tourism experiences are presented. We show how Time Trails can be used as a presencing tool to establish new ways of encountering and learning on digital heritage within our daily lives. Keywords: Presencing. Digital Heritage. Mixed Reality. Trajectories. Community. RÉSUMÉ – Time Trails: patrimoine numérique en présence dans notre quotidien – Le projet Time Trails est le résultat d’une collaboration entre le Centre for Intermedia de l’University of Ex- eter, le Royal Albert Memorial Museum and Art Gallery, le 1010 Media et l’Exeter City Football Club Supporters Trust (2013). C’est une application web conçue pour des dispositifs mobiles et qui permet aux usagers de suivre, de commenter et de créer des scénarios en utilisant du texte, des images et des vidéo, diffusés via les réseaux sociaux. -

Modern British and Irish Art I Montpelier Street, London I 3 July 2019 25378

Montpelier Street, London I 3 July 2019 Montpelier Street, Modern British and Irish Art British and Irish Modern Modern British and Irish Art I Montpelier Street, London I 3 July 2019 25378 Modern British and Irish Art Montpelier Street, London | Wednesday 3 July 2019, at 1pm BONHAMS BIDS ENQUIRIES IMPORTANT INFORMATION Montpelier Street +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 Janet Hardie The United States Government Knightsbridge +44 (0) 20 7447 7401 fax Specialist has banned the import of ivory London SW7 1HH [email protected] +44 (0) 20 7393 3949 into the USA. Lots containing www.bonhams.com [email protected] ivory are indicated by the symbol To bid via the internet please Ф printed beside the lot number VIEWING visit www.bonhams.com Catherine White in this catalogue. Junior Cataloguer Sunday 30 June Please note that bids should be +44 (0) 20 7393 3884 11am to 3pm REGISTRATION submitted no later than 4pm [email protected] Monday 1 July IMPORTANT NOTICE on the day prior to the auction. Please note that all customers, 9am to 4.30pm New bidders must also provide irrespective of any previous activity Tuesday 2 July PRESS ENQUIRIES proof of identity when submitting with Bonhams, are required to 9am to 4.30pm [email protected] bids. Failure to do this may result complete the Bidder Registration Wednesday 3 July Form in advance of the sale. The in your bids not being processed. CUSTOMER SERVICES 9am to 11am form can be found at the back of Bidding by telephone will only be Monday to Friday every catalogue and on our ILLUSTRATIONS accepted on a lot with the lower 8.30am – 6pm website at www.bonhams.com Front Cover: Lot 173 estimate in excess of £500.