The Iconography of O'connell Street and Environs After Independence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Short History of Irish Memory in the Long Twentieth Century

Thomas Bartlett (ed.), The Cambridge History of Ireland Irish Memory in the Long Twentieth Century (Cambridge, 2018), vol. IV: 1800 to Present would later be developed by his disciple Maurice Halbwachs, who coined the term collective memory ('la memoire collective'). By calling attention to the social frameworks in which memory is framed ('les cadres sociaux de la 23 · memoire'), Halbwachs presented a sound theoretical model for understand ing how individual members of a society collectively remember their past. 3 A Short History of Irish Memory in The impression that modernisation had uprooted people from tradition and the Long Twentieth Century that mass society suffered from atomised impersonality gave birth to a vogue GUY BEINER for commemoration, which was seen as a fundamental act of communal soli darity, in that it projected an illusion of continuity with the past.4 Ireland, outside of Belfast, did not undergo industrialisation on a scale comparable with England, and yet Irish society was not spared the upheaval On the cusp of the twentieth century; Ireland was obsessed with memoriali of modernity. The Great Famine had decimated vernacular Gaelic culture sation. This condition reflected a transnational zeitgeist that was indicative of and resulted in massive emigration. An Irish variant of fin de siecle angst over a crisis of memory throughout Europe. The outcome of rapid modernisa degeneration fed on apprehensions that British rule would ultimately result tion, manifested through changes ushered in by such far-reaching processes in the loss of 'native' identity. The perceived threat to national culture, artic as industrialisation, urbanisation, commercialisation and migration, raised ulated in Douglas Hyde's manifesto on 'The Necessity for De-Anglicising fears that the rituals and customs through which the past had been habitually Ireland' (1892), stimulated a vigorous response in the form of the Irish Revival remembered in the countryside were destined to be swept away. -

February, 1955

Library of The Harvard Musical Association Bulletin No. 23 February, 1955 Library Committee CHARLES R. NUTTER JOHN N. BURK RICHARD G. APPEL CYRUS DURGIN RUDOLPH ELIE Director of the Library and Library and Custodian of the Marsh Room Marsh Room Marsh Room CHARLES R. NUTTER MURIEL FRENCH FLORENCE C. ALLEN To the Members of the Association: Your attention is called to an article in this issue by Albert C. Koch. * * * * REPORT ON THE LIBRARY AND ON THE MARSH ROOM FOR THE YEAR 1954 To the President and the Directors of The Harvard Musical Association: Today, when television and the radio, both A.M. and F.M., are providing much of the intellectual sustenance for the common man and woman, the individual who turns for an intellectual repast to the writers of past centuries and also tries to phrase his thoughts both vocal and written with some regard to the rules of grammar and the principles of rhetoric is regarded as high‐brow and is thrown out of society. I am aware that I lay myself open to the charge of being a high‐brow, a charge that creates no reactionary emotion at all, especially as it comes usually from the low‐brow, and that I may be thrown out of society into a lower stratum, when I state that for the text of this report I have turned to a gentleman whose mortal life spanned the years between 1672 and 1719. Even the low‐brow has probably heard or read the name Joseph Addison, though it may convey nothing to him except the fact that it has an English and not a foreign sound. -

1 Clontarf 1014

Clontarf 1014 – a battle of the clans? 1. The contemporary record In its account of the battle of Clontarf the northern AU report that Brian, son of Cennétig, king of Ireland, and Máel Sechnaill mac Domnaill, king of Tara, led an army to Dublin (Áth Cliath) • all of the Leinsterman (Laigin) were assembled to meet him (Brian), the foreigners of Áth Cliath, and a similar number of foreigners of Lochlainn (Scotland) • a sterling battle was fought between them, the like of which had never been encountered before Then the foreigners and the Leinstermen first broke in defeat and were completely wiped out • there fell on the side of the foreign troop Máel Mórda, king of Leinster, and Domnall, king of the Forthuatha • of the foreigners fell Dubgall, son of Amlaíb (= Óláfr), Sigurd, earl (jarl) of Orkney, and Gilla Ciaráin, heir designate of the foreigners, etc. • Brodar who slew Brian, chief of the Scandinavian fleet, together with 6,000 others was also killed or drowned Of the Irish who fell in the counter-shock were Brian, overking of the Irish of Ireland and of the foreigners [of Limerick and Waterford] and of the Britons [of Wales?], the Augustus of the whole of the north-west of Europe [= Ireland] • his son Murchad and the latter’s son Tairdelbach, Conaing, the heir designate of Mumu, Mothla, king of the Déisi Muman, etc. • the list includes numerous kings of various parts of Munster, plus Domnall, the earl of Marr in Scotland • this list carries conviction when analysed against known details The southern AI report similarly, though more -

Visualising Victoria: Gender, Genre and History in the Young Victoria (2009)

Visualising Victoria: Gender, Genre and History in The Young Victoria (2009) Julia Kinzler (Friedrich-Alexander-University Erlangen-Nuremberg, Germany) Abstract This article explores the ambivalent re-imagination of Queen Victoria in Jean-Marc Vallée’s The Young Victoria (2009). Due to the almost obsessive current interest in Victorian sexuality and gender roles that still seem to frame contemporary debates, this article interrogates the ambiguous depiction of gender relations in this most recent portrayal of Victoria, especially as constructed through the visual imagery of actual artworks incorporated into the film. In its self-conscious (mis)representation of Victorian (royal) history, this essay argues, The Young Victoria addresses the problems and implications of discussing the film as a royal biopic within the generic conventions of heritage cinema. Keywords: biopic, film, gender, genre, iconography, neo-Victorianism, Queen Victoria, royalty, Jean-Marc Vallée. ***** In her influential monograph Victoriana, Cora Kaplan describes the huge popularity of neo-Victorian texts and the “fascination with things Victorian” as a “British postwar vogue which shows no signs of exhaustion” (Kaplan 2007: 2). Yet, from this “rich afterlife of Victorianism” cinematic representations of the eponymous monarch are strangely absent (Johnston and Waters 2008: 8). The recovery of Queen Victoria on film in John Madden’s visualisation of the delicate John-Brown-episode in the Queen’s later life in Mrs Brown (1997) coincided with the academic revival of interest in the monarch reflected by Margaret Homans and Adrienne Munich in Remaking Queen Victoria (1997). Academia and the film industry brought the Queen back to “the centre of Victorian cultures around the globe”, where Homans and Munich believe “she always was” (Homans and Munich 1997: 1). -

New Editions 2012

January – February 2013 Volume 2, Number 5 New Editions 2012: Reviews and Listings of Important Prints and Editions from Around the World • New Section: <100 Faye Hirsch on Nicole Eisenman • Wade Guyton OS at the Whitney • Zarina: Paper Like Skin • Superstorm Sandy • News History. Analysis. Criticism. Reviews. News. Art in Print. In print and online. www.artinprint.org Subscribe to Art in Print. January – February 2013 In This Issue Volume 2, Number 5 Editor-in-Chief Susan Tallman 2 Susan Tallman On Visibility Associate Publisher New Editions 2012 Index 3 Julie Bernatz Managing Editor Faye Hirsch 4 Annkathrin Murray Nicole Eisenman’s Year of Printing Prodigiously Associate Editor Amelia Ishmael New Editions 2012 Reviews A–Z 10 Design Director <100 42 Skip Langer Design Associate Exhibition Reviews Raymond Hayen Charles Schultz 44 Wade Guyton OS M. Brian Tichenor & Raun Thorp 46 Zarina: Paper Like Skin New Editions Listings 48 News of the Print World 58 Superstorm Sandy 62 Contributors 68 Membership Subscription Form 70 Cover Image: Rirkrit Tiravanija, I Am Busy (2012), 100% cotton towel. Published by WOW (Works on Whatever), New York, NY. Photo: James Ewing, courtesy Art Production Fund. This page: Barbara Takenaga, detail of Day for Night, State I (2012), aquatint, sugar lift, spit bite and white ground with hand coloring by the artist. Printed and published by Wingate Studio, Hinsdale, NH. Art in Print 3500 N. Lake Shore Drive Suite 10A Chicago, IL 60657-1927 www.artinprint.org [email protected] No part of this periodical may be published without the written consent of the publisher. -

John L. Burke Papers

Leabharlann Naisiúnta na hÉireann National Library of Ireland Collection List No. 63 JOHN L. BURKE PAPERS (Mss 34,246-34,249; 36,100-36,125) ACC. Nos. 4829, 5135, 5258, 5305 INTRODUCTION The papers of John Leo Burke (1888-1959) were donated to the National Library of Ireland by his daughter Miss Ann Burke. The major part of this Collection was received in two sections in September 1997 and January 2000 (Accession 5135). Other material was donated as follows: September 1994 (Accession 4829); June 1998 (Accession 5258) and November 1998 (Accession 5305). These various accruals have been consolidated in this List. The Collection also includes a biographical note on John Leo Burke by Robert Tracy (MS 36,125(4)). LETTERS TO JOHN L. BURKE MS 36,100(1) Actors’ Church Union. Irish Branch 1953 Oct.: Circular in support of the Irish Branch. Autograph signature of Lennox Robinson. 1 printed item. MS 36,100(2) Allgood, Sara 1923 Dec. 12: Thanking JLB for sending story; Abbey production of T.C. Murray’s Birthright. 1 sheet + cover. MS 36,100(3) Bodkin, Thomas 1959 June 16: Gift of print for John Costello. Portrait of Joyce. Unhappy about conditions at National Gallery – “God save us all from the machinations of incompetence.” 1 sheet. MS 36,100(4) Colum, Padraic 1949 Sept. 6: Thanking JLB for photograph of Joyce. Good quality of articles in The Shanachie. “Joyce used to frequent Aux Trianons, opposite Gare Montparnasse. The food is good …”. 1 sheet + cover. MS 36,100(5-6) Cosgrave, W. T. 2 items: Undated: Christmas card. -

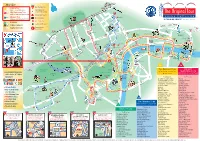

A4 Web Map 26-1-12:Layout 1

King’s Cross Start St Pancras MAP KEY Eurostar Main Starting Point Euston Original Tour 1 St Pancras T1 English commentary/live guides Interchange Point City Sightseeing Tour (colour denotes route) Start T2 W o Language commentaries plus Kids Club REGENT’S PARK Euston Rd b 3 u Underground Station r n P Madame Tussauds l Museum Tour Russell Sq TM T4 Main Line Station Gower St Language commentaries plus Kids Club q l S “A TOUR DE FORCE!” The Times, London To t el ★ River Cruise Piers ss Gt Portland St tenham Ct Rd Ru Baker St T3 Loop Line Gt Portland St B S s e o Liverpool St Location of Attraction Marylebone Rd P re M d u ark C o fo t Telecom n r h Stansted Station Connector t d a T5 Portla a m Museum Tower g P Express u l p of London e to S Aldgate East Original London t n e nd Pl t Capital Connector R London Wall ga T6 t o Holborn s Visitor Centre S w p i o Aldgate Marylebone High St British h Ho t l is und S Museum el Bank of sdi igh s B tch H Gloucester Pl s England te Baker St u ga Marylebone Broadcasting House R St Holborn ld d t ford A R a Ox e re New K n i Royal Courts St Paul’s Cathedral n o G g of Justice b Mansion House Swiss RE Tower s e w l Tottenham (The Gherkin) y a Court Rd M r y a Lud gat i St St e H n M d t ill r e o xfo Fle Fenchurch St Monument r ld O i C e O C an n s Jam h on St Tower Hill t h Blackfriars S a r d es St i e Oxford Circus n Aldwyc Temple l a s Edgware Rd Tower Hil g r n Reg Paddington P d ve s St The Monument me G A ha per T y Covent Garden Start x St ent Up r e d t r Hamleys u C en s fo N km Norfolk -

![Stpat [Compatibility Mode]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6747/stpat-compatibility-mode-686747.webp)

Stpat [Compatibility Mode]

20/03/2018 A short Tour of Ireland 1 20/03/2018 Traditional Irish dancing • https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wXb7pEEcWq0 – local festival • https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HgGAzBDE454 – riverdance • https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R9KkbU4yStM – riverdance2 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wmokDwpepGI 5 top Irish myths Facts Size: 486Km by 275Km Population 4.8M in Rep Ireland +1.8M in N.Ireland Diaspora 80M – US, UK, Aus Weather – unpredictable Main conversation topic 3 deg to 23 deg – Rain 150-250 days/year Tourists – 10 M per year 200K are French Popular places; Dublin, SW & N. Ireland 2 20/03/2018 Brief History of Ireland - 1 • 4000 BC first farmers arrived – Stone Age • 300 BC Celts - iron age warriors from mainland Europe – celtic language & traditions • 600 AD– Christian missionaries – St Patrick – Irish christian scolars exceled at Latin , Greek & theology - Book of Kells crafted • 900AD - Vikings arrived from Scandanavia, invaded & settled - founding of Dublin capital city in 988 • 1014 – Irish chief – Brian Boru defeated Vikings at Battle of Clontarf • 12 th century – arrival of Normans, - walled towns, churches, increase in agriculture & commerce • 16 th century – King Henry VIII declared himself king of Ireland (1541) – plantation of English & Scottish protestant landlords – start sectarian conflict Brief History of Ireland - 2 • 17 th Century – Penal laws - disempower catholics - irish owned 5% land • 1782 – favorable trading agreement with UK – Henry Grattan • 1829 – Act of Catholic Emancipation - Daniel O Connell – great liberator • Act of the union – set up of Irish Government • 1845 – The great Famine, blight hit potato crops – starvation & emigration. pop decreased from 8M to 4.5M people over 5 years • 1912 – Home rule Act - then suspended with WW1 in 1914 • 1916 – Easter Rising – Irish rebels seized key locations (GPO) in Dublin – P Pearse & J. -

NAMA Annual Report and Financial Statements 2014

Annual Report & Financial Statements 2014 Contents LETTER TO THE MINISTER FOR FINANCE 1 KEY OBJECTIVES SET BY THE NAMA BOARD 2 KEY PERFORMANCE INDICATORS 3 OTHER KEY BUSINESS HIGHLIGHTS 4 CHAIRMAN’S STATEMENT 6 CHIEF EXECUTIVE’S STATEMENT 8 10-29 BUSINESS REVIEW Debtor engagement 11 NAMA market activity 14 Development funding 20 Social and economic contribution 25 30-41 FINANCIAL REVIEW 42-48 NAMA ORGANISATION AND SERVICE PROVIDERS Organisational structure 43 Service providers to NAMA 48 49-65 GOVERNANCE Board members 50 Board and Committees of the Board 52 Reports from Chairpersons of NAMA committees 54 Disclosure and accountability 64 Risk management 65 66-170 CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Glossary of terms 171 HIGHLIGHTS BUSINESS REVIEW BUSINESS FINANCIAL REVIEW 12 May 2015 Mr. Michael Noonan T.D. ORGANISATIONAL STRUCTURE ORGANISATIONAL Minister for Finance Government Buildings Upper Merrion Street Dublin 2. Dear Minister, GOVERNANCE We have the honour to submit to you the Report and Accounts of the National Asset Management Agency for the year ended 31 December 2014. Yours sincerely, FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Frank Daly Brendan McDonagh Chairman Chief Executive WWW.NAMA.IE 1 ANNUAL REPORT & FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 2014 Key Strategic Objectives set by the NAMA Board The Board’s primary commercial objective is to redeem all of its senior debt (€30.2 billion) before the end of 2018. The Board also 1. aims to redeem the NAMA subordinated debt (€1.593 billion) by 1 March 2020 and to generate a surplus by the time its work has been completed. It aims to meet all of its future commitments out of its own resources. -

Battle of Clontarf by Finnegan

Clontarf We are in the year 1014, on the coast of Ireland. Brian Boru high king of the emerald isle awaits the battle that will either crush the rising rebellion, or mark his defeat. This battle will go down in history as the battle of Clontarf… A cool gust of wind buffeted from the sea, ruffling the lush green grass as it tore across the plain. His woolen cloak drawn closely around him, Aengus paced before the tents. Many faces were staring anxiously at the grey horizon as they went about sharpening swords, counting arrows and getting readying for the battle to come. In the distance a flicker could be observed at the base of the horizon. It grew to form a small group of riders who hustled across the plain as they saw the host by the Clontarf coast. Brian Boru rode at the center, his white beard tussled by the wind, the banner of his clan, the dal Cais, blowing behind him. In that that day no man in Ireland did not know of Brian Boru, and his name was uttered countless times. No man before had done what he had done. He alone ruled the south half of Ireland, having left the entire north to his former enemy Maél Sechnaill. Now with a rebellion from Leinster and Dublin on the rise, Brian was calling on this Sechnaill in hopes of gaining his support in the inevitable battle. Murchad appeared silently behind Aengus. “Dia dhuit?” he greeted. “Dia is Muire dhuit.” Aengus answered absently. “You think they bring good news?” “I hope, the Norse of Dublin are a force to be reckoned with- we need all the help we can get.” “Aye, but I’d rather that it weren’t from a snake like that Sechnaill.” Murchad had been something of a brother to Aengus for as long as either of them could remember. -

Ireland in Brief in Ireland .Ie Céad Míle Fáilte Reddog Design Www

Ireland in Brief .ie Céad Míle Fáilte reddog design_www. Ireland in Brief A general overview of Ireland’s political, economic and cultural life Iveagh House, headquarters of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Dublin. Map of Ireland overleaf www.dfat.ie Ireland in Brief .ie Céad Míle Fáilte reddog design_www. Ireland in Brief A general overview of Ireland’s political, economic and cultural life Iveagh House, headquarters of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Dublin. Map of Ireland overleaf www.dfat.ie Photo credits 2 Fernando Carniel Machado / Thinkstock 4 Houses of the Oireachtas 7 CAPT Vincenzo Schettini / Department of Defence 8 © National Museum of Ireland 15 Paul Rowe / Educate Together 18 Trinity College Dublin 19 Dublin Port Company 20 Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade 24 RTE / John Cooney 27 Maxwells 28 Irish Medical News 33 Press Association 35 Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade 36 Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade 38 Department of the Taoiseach 39 Irish Aid 41 Department of the Taoiseach 42 Collection Irish Museum of Modern Art, Donation Gordon Lambert Trust, 1992. 45 © John Minehan 46 © National Gallery of Ireland 49 Denis Gilbert 50 Colm Hogan 51 Irish Film Board 52 Irish Film Board 54 Sportsfile / Stephen McCarthy 55 Sportsfile / Brian Lawless 56 Sportsfile / David Maher Ordnance Survey Ireland Permit No. 8670 © Ireland/Government of Contents This booklet provides a general overview of Ireland’s political, economic and cultural life. While it is not possible to include every aspect of life in Ireland in this short publication, we hope that you will discover a little about Ireland and its people. -

2009 Annual Report

Annual Report Dublin City Business Improvement District 2009 Creating A Better City For All Dublin City Business Improvement District Mission Statement The Dublin City Business Improvement District is a not-for-profit organisation that works on behalf of its members to create an attractive, welcoming, vibrant and economically successful BID area. We achieve this by delivering a range of cost-effective improvements, enhancing the perception of our city and by working in partnership with city authorities and other stakeholders. 2 q BID Annual Report 2009 BID Welcome Chairman’s Address In just two years the BID is well ahead of schedule, having Andrew Diggins, already completed projects which were expected to take BID Chairperson five years. In addition, the rest of the programme is well on the way to completion within the original timeframe, this process. The board of directors has also established despite the fact that the programme has come in well three key policy groups in the areas of Public Domain, Civic under budget. Assurance and Marketing. These groups will oversee the implementation of the actions envisaged in the strategic The environment in which we operate has changed plan and suggest additional actions. fundamentally from that envisaged when the BID was proposed in June 2007. Therefore, a key task for the BID Our vision is ambitious and we believe that, when fully board of directors in the last year has been to consider not implemented, it will transform the trading environment for only what the BID does but how it does it. the benefit of Dublin’s many stakeholders.