Our Volcano Neighbors Patch Program

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Pictorial Summary of the Life and Work of George Patrick Leonard Walker

A pictorial summary of the life and work of George Patrick Leonard Walker SCOTT K. ROWLAND1* & R. S. J. SPARKS2 1Department of Geology and Geophysics, University of Hawaii at Manoa, 1680 East–West Road, Honolulu, Hawaii, USA 2Department of Earth Sciences, University of Bristol, Bristol BS8 1RJ, UK *Corresponding author (e-mail: [email protected]) Abstract: George Patrick Leonard Walker was one of the fathers of modern volcanology. He worked in many parts of the world and contributed to the understanding of a huge range of volca- nological processes. He was a field geologist at heart, and one of his greatest skills was the ability to quantify volcanological ideas – not with obscure statistical treatments or complex numerical models, but with clear graphical relationships supported by tremendous amounts of carefully col- lected field data. Here we present some glimpses of his life and work in photographs and diagrams. George Walker was born on 2 March 1926 in Iceland, as well as to India, Italy, the Azores and London. In 1939, when he was 13, the family Africa, among other locations. In 1978 George moved to Northern Ireland. In 1948 and 1949, moved to the University of Auckland and in 1982 respectively, George received his Bachelors and he moved to the University of Hawaii. Over the Masters degrees from Queen’s University, Belfast. span of his career he visited almost every volcanic In 1956 he completed his PhD at the University of region in the world, including Australia, the Azores, Leeds with a dissertation on secondary minerals in the Canary Islands, Chile, China, Costa Rica, igneous rocks of Northern Iceland. -

Source to Surface Model of Monogenetic Volcanism: a Critical Review

Downloaded from http://sp.lyellcollection.org/ by guest on September 28, 2021 Source to surface model of monogenetic volcanism: a critical review I. E. M. SMITH1 &K.NE´ METH2* 1School of Environment, University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand 2Volcanic Risk Solutions, Massey University, Palmerston North 4442, New Zealand *Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Small-scale volcanic systems are the most widespread type of volcanism on Earth and occur in all of the main tectonic settings. Most commonly, these systems erupt basaltic magmas within a wide compositional range from strongly silica undersaturated to saturated and oversatu- rated; less commonly, the spectrum includes more siliceous compositions. Small-scale volcanic systems are commonly monogenetic in the sense that they are represented at the Earth’s surface by fields of small volcanoes, each the product of a temporally restricted eruption of a composition- ally distinct batch of magma, and this is in contrast to polygenetic systems characterized by rela- tively large edifices built by multiple eruptions over longer periods of time involving magmas with diverse origins. Eruption styles of small-scale volcanoes range from pyroclastic to effusive, and are strongly controlled by the relative influence of the characteristics of the magmatic system and the surface environment. Gold Open Access: This article is published under the terms of the CC-BY 3.0 license. Small-scale basaltic magmatic systems characteris- hazards associated with eruptions, and this is tically occur at the Earth’s surface as fields of small particularly true where volcanic fields are in close monogenetic volcanoes. These volcanoes are the proximity to population centres. -

Anatomy of a Volcanic Eruption: Case Study: Mt. St. Helens

Anatomy of a Volcanic Eruption: Case Study: Mt. St. Helens Materials Included in this Box: • Teacher Background Information • 3-D models of Mt. St. Helens (before and after eruption) • Examples of stratovolcano rock products: Tuff (pyroclastic flow), pumice, rhyolite/dacite, ash • Sandbox crater formation exercise • Laminated photos/diagrams Teacher Background There are several shapes and types of volcanoes around the world. Some volcanoes occur on the edges of tectonic plates, such as those along the ‘ring of fire’. But there are also volcanoes that occur in the middle of tectonic plates like the Yellowstone volcano and Kilauea volcano in Hawaii. When asked to draw a volcano most people will draw a steeply sided, conical mountain that has a depression (crater) at the top. This image of a 'typical' volcano is called a stratovolcano (a.k.a. composite volcano). While this is the often visualized image of a volcano, there are actually many different shapes volcanoes can be. A volcano's shape is mostly determined by the type of magma/lava that is created underneath it. Stratovolcanoes get their shape because of the thick, sticky (viscous) magma that forms at subduction zones. This magma/lava is layered between ash, pumice, and rock fragments. These layers of ash and magma will build into high elevation, steeply sided, conical shaped mountains and form a 'typical' volcano shape. Stratovolcanoes are also known for their explosive and destructive eruptions. Eruptions can cause clouds of gas, ash, dust, and rock fragments to eject into the atmosphere. These clouds of ash can become so dense and heavy that they quickly fall down the side of the volcanoes as a pyroclastic flow. -

The Science Behind Volcanoes

The Science Behind Volcanoes A volcano is an opening, or rupture, in a planet's surface or crust, which allows hot magma, volcanic ash and gases to escape from the magma chamber below the surface. Volcanoes are generally found where tectonic plates are diverging or converging. A mid-oceanic ridge, for example the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, has examples of volcanoes caused by divergent tectonic plates pulling apart; the Pacific Ring of Fire has examples of volcanoes caused by convergent tectonic plates coming together. By contrast, volcanoes are usually not created where two tectonic plates slide past one another. Volcanoes can also form where there is stretching and thinning of the Earth's crust in the interiors of plates, e.g., in the East African Rift, the Wells Gray-Clearwater volcanic field and the Rio Grande Rift in North America. This type of volcanism falls under the umbrella of "Plate hypothesis" volcanism. Volcanism away from plate boundaries has also been explained as mantle plumes. These so- called "hotspots", for example Hawaii, are postulated to arise from upwelling diapirs with magma from the core–mantle boundary, 3,000 km deep in the Earth. Erupting volcanoes can pose many hazards, not only in the immediate vicinity of the eruption. Volcanic ash can be a threat to aircraft, in particular those with jet engines where ash particles can be melted by the high operating temperature. Large eruptions can affect temperature as ash and droplets of sulfuric acid obscure the sun and cool the Earth's lower atmosphere or troposphere; however, they also absorb heat radiated up from the Earth, thereby warming the stratosphere. -

Mars Field Geology, Biology, and Paleontology Workshop, Summary

MARS FIELD GEOLOGY, BIOLOGY, AND PALEONTOLOGY WORKSHOP: SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS November 18–19, 1998 Space Center Houston, Houston, Texas LPI Contribution No. 968 MARS FIELD GEOLOGY, BIOLOGY, AND PALEONTOLOGY WORKSHOP: SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS November 18–19, 1998 Space Center Houston Edited by Nancy Ann Budden Lunar and Planetary Institute Sponsored by Lunar and Planetary Institute National Aeronautics and Space Administration Lunar and Planetary Institute 3600 Bay Area Boulevard Houston TX 77058-1113 LPI Contribution No. 968 Compiled in 1999 by LUNAR AND PLANETARY INSTITUTE The Institute is operated by the Universities Space Research Association under Contract No. NASW-4574 with the National Aeronautcis and Space Administration. Material in this volume may be copied without restraint for library, abstract service, education, or personal research purposes; however, republication of any paper or portion thereof requires the written permission of the authors as well as the appropriate acknowledgment of this publication. This volume may be cited as Budden N. A., ed. (1999) Mars Field Geology, Biology, and Paleontology Workshop: Summary and Recommendations. LPI Contribution No. 968, Lunar and Planetary Institute, Houston. 80 pp. This volume is distributed by ORDER DEPARTMENT Lunar and Planetary Institute 3600 Bay Area Boulevard Houston TX 77058-1113 Phone: 281-486-2172 Fax: 281-486-2186 E-mail: [email protected] Mail order requestors will be invoiced for the cost of shipping and handling. _________________ Cover: Mars test suit subject and field geologist Dean Eppler overlooking Meteor Crater, Arizona, in Mark III Mars EVA suit. PREFACE In November 1998 the Lunar and Planetary Institute, under the sponsorship of the NASA/HEDS (Human Exploration and Development of Space) Enterprise, held a workshop to explore the objectives, desired capabilities, and operational requirements for the first human exploration of Mars. -

Educators Guide

EDUCATORS GUIDE 02 | Supervolcanoes Volcanism is one of the most creative and destructive processes on our planet. It can build huge mountain ranges, create islands rising from the ocean, and produce some of the most fertile soil on the planet. It can also destroy forests, obliterate buildings, and cause mass extinctions on a global scale. To understand volcanoes one must first understand the theory of plate tectonics. Plate tectonics, while generally accepted by the geologic community, is a relatively new theory devised in the late 1960’s. Plate tectonics and seafloor spreading are what geologists use to interpret the features and movements of Earth’s surface. According to plate tectonics, Earth’s surface, or crust, is made up of a patchwork of about a dozen large plates and many smaller plates that move relative to one another at speeds ranging from less than one to ten centimeters per year. These plates can move away from each other, collide into each other, slide past each other, or even be forced beneath each other. These “subduction zones” are generally where the most earthquakes and volcanoes occur. Yellowstone Magma Plume (left) and Toba Eruption (cover page) from Supervolcanoes. 01 | Supervolcanoes National Next Generation Science Standards Content Standards - Middle School Content Standards - High School MS-ESS2-a. Use plate tectonic models to support the HS-ESS2-a explanation that, due to convection, matter Use Earth system models to support cycles between Earth’s surface and deep explanations of how Earth’s internal and mantle. surface processes operate concurrently at different spatial and temporal scales to MS-ESS2-e form landscapes and seafloor features. -

Periodic Behavior in Lava Dome Eruptions

Earth and Planetary Science Letters 199 (2002) 173^184 www.elsevier.com/locate/epsl Periodic behavior in lava dome eruptions A. Barmin a, O. Melnik a;b, R.S.J. Sparks b;Ã a Institute of Mechanics, Moscow State University, 1-Michurinskii prosp., Moscow 117192, Russia b Centre for Geophysical and Environmental Flows, Department of Earth Sciences, University of Bristol, Wills Memorial Building, Queen’s Road, Bristol BS8 1RJ, UK Received 16 September 2001; accepted 20 February 2002 Abstract Lava dome eruptions commonly display fairly regular alternations between periods of high activity and periods of low or no activity. The time scale for these alternations is typically months to several years. Here we develop a generic model of magma discharge through a conduit from an open-system magma chamber with continuous replenishment. The model takes account of the principal controls on flow, namely the replenishment rate, magma chamber size, elastic deformation of the chamber walls, conduit resistance, and variations of magma viscosity, which are controlled by degassing during ascent and kinetics of crystallization. The analysis indicates a rich diversity of behavior with periodic patterns similar to those observed. Magma chamber size can be estimated from the period with longer periods implying larger chambers. Many features observed in volcanic eruptions such as alternations between periodic behaviors and continuous discharge, sharp changes in discharge rate, and transitions from effusive to catastrophic explosive eruption can be understood in terms of the non-linear dynamics of conduit flows from open-system magma chambers. The dynamics of lava dome growth at Mount St. Helens (1980^1987) and Santiaguito (1922^2000) was analyzed with the help of the model. -

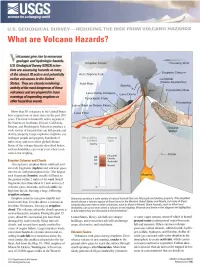

What Are Volcano Hazards?

USGS science for a changing world U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY REDUCING THE RISK FROM VOLCANO HAZARDS What are Volcano Hazards? \7olcanoes give rise to numerous T geologic and hydrologic hazards. Eruption Cloud Prevailing Wind U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) scien tists are assessing hazards at many Eruption Column of the almost 70 active and potentially Ash (Tephra) Fall active volcanoes in the United Landslide (Debris Avalanche) States. They are closely monitoring Acid Rain Bombs activity at the most dangerous of these Pyroclastic Flow volcanoes and are prepared to issue Lava Dome Collapse x Lava Dome warnings of impending eruptions or Pyroclastic Flow other hazardous events. Lahar (Mud or Debris Flow)jX More than 50 volcanoes in the United States Lava Flow have erupted one or more times in the past 200 years. The most volcanically active regions of the Nation are in Alaska, Hawaii, California, Oregon, and Washington. Volcanoes produce a wide variety of hazards that can kill people and destroy property. Large explosive eruptions can endanger people and property hundreds of miles away and even affect global climate. Some of the volcano hazards described below, such as landslides, can occur even when a vol cano is not erupting. Eruption Columns and Clouds An explosive eruption blasts solid and mol ten rock fragments (tephra) and volcanic gases into the air with tremendous force. The largest rock fragments (bombs) usually fall back to the ground within 2 miles of the vent. Small fragments (less than about 0.1 inch across) of volcanic glass, minerals, and rock (ash) rise high into the air, forming a huge, billowing eruption column. -

GSA TODAY December Vol

Vol. 5, No. 12 December 1995 INSIDE • New Members, Fellows, Student Associates, p. 247 GSA TODAY South-Central Section Meeting, p. 250 • A Publication of the Geological Society of America • Northeastern Section Meeting, p. 253 Seismic Images of the A B Core-Mantle Boundary Michael E. Wysession, Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Washington University, St. Louis, MO 63130 C D ABSTRACT INTRODUCTION Seismology presents several ways While most geologists, including of providing images of the geologic specialists in the field of seismology, structures that exist in the lowermost study rocks at Earth’s surface, more mantle just above the core-mantle attention also is being paid to the boundary (CMB). An understanding planet’s other major boundary, that of the possibly complex geophysical between the core and mantle. With a E F processes occurring at this major density jump of 4.3 kg/m3 between discontinuity requires the combined the silicate lower mantle and the liquid efforts of many fields, but it is the iron outer core, as well as a tempera- role of seismology to geographically ture increase of possibly 1500 °C map out this largely uncharted terri- between the lower mantle adiabat and tory. Seismic phases that reflect, outer core, the core-mantle boundary diffract, and refract across the CMB (CMB) may well be Earth’s most signifi- can all be used to provide different cant and dramatic discontinuity. Our Figure 1. Images from a motion picture showing the propagation of seismic shear energy information in different ways. increasing knowledge of this highly through the mantle (Wysession and Shore, 1994). -

UAS-Based Tracking of the Santiaguito Lava Dome, Guatemala

Boise State University ScholarWorks Geosciences Faculty Publications and Presentations Department of Geosciences 5-25-2020 UAS-Based Tracking of the Santiaguito Lava Dome, Guatemala Edgar U. Zorn German Research Centre for Geosciences GFZ Thomas R. Walter German Research Centre for Geosciences GFZ Jeffrey B. Johnson Boise State University René Mania German Research Centre for Geosciences GFZ Publication Information Zorn, Edgar U.; Walter, Thomas R.; Johnson, Jeffrey B.; and Mania, René. (2020). "UAS-Based Tracking of the Santiaguito Lava Dome, Guatemala". Scientific Reports, 10, 8644-1 - 8644-13. https://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/s41598-020-65386-2 www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN UAS-based tracking of the Santiaguito Lava Dome, Guatemala Edgar U. Zorn1 ✉ , Thomas R. Walter1, Jefrey B. Johnson2 & René Mania1 Imaging growing lava domes has remained a great challenge in volcanology due to their inaccessibility and the severe hazard of collapse or explosion. Changes in surface movement, temperature, or lava viscosity are considered crucial data for hazard assessments at active lava domes and thus valuable study targets. Here, we present results from a series of repeated survey fights with both optical and thermal cameras at the Caliente lava dome, part of the Santiaguito complex at Santa Maria volcano, Guatemala, using an Unoccupied Aircraft System (UAS) to create topography data and orthophotos of the lava dome. This enabled us to track pixel-ofsets and delineate the 2D displacement feld, strain components, extrusion rate, and apparent lava viscosity. We fnd that the lava dome displays motions on two separate timescales, (i) slow radial expansion and growth of the dome and (ii) a narrow and fast- moving lava extrusion. -

1998 Volcanic Activity in Alaska and Kamchatka: Summary of Events and Response of the Alaska Volcano Observatory by Robert G

1998 Volcanic Activity in Alaska and Kamchatka: Summary of Events and Response of the Alaska Volcano Observatory by Robert G. McGimsey, Christina A. Neal, and Olga Girina Open-File Report 03-423 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey 1998 Volcanic Activity in Alaska and Kamchatka: Summary of Events and Response of the Alaska Volcano Observatory By Robert G. McGimsey1, Christina A. Neal1, and Olga Girina2 1Alaska Volcano Observatory, 4200 University Dr., Anchorage, AK 99508-4664 2Kamchatka Volcanic eruptions Response Team, Institute of Volcanic Geology and Geochemistry, Piip Blvd., 9 Petropavlovsk-Kam- chatsky, 683006, Russia AVO is a cooperative program of the U.S. Geological Survey, University of Alaska Fairbanks Geophysical Institute, and the Alaska Division of Geological and Geophysical Surveys. AVO is funded by the U.S. Geological Survey Volcano Hazards Program and the State of Alaska Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government Open-File Report 03-423 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction. 1 Reports of volcanic activity, northeast to southwest along Aleutian arc . 4 Shrub Mud Volcano . 4 Augustine Volcano . 6 Becharof Lake Area . 8 Chiginagak Volcano . 10 Shishaldin Volcano. 12 Akutan Volcano . 12 Korovin Volcano . 13 Reports of Volcanic activity, Kamchatka, Russia, North to South . 15 Sheveluch Volcano . 17 Klyuchevskoy Volcano. 19 Bezymianny Volcano . 21 Karymsky Volcano . 23 References. 24 Acknowledgments . 26 Figures 1 A. Map location of historically active volcanoes in Alaska and place names used in this summary . -

Structural Analysis of Silicic Lava Flow Margins at Obsidian Dome, California

Structural Analysis of Silicic Lava Flow Margins at Obsidian Dome, California by Abigail Martens, B.S. A Thesis Submitted to the Department of Geological Sciences California State University Bakersfield In Partial Fulfillment for the Degree of Masters of Geology Spring 2017 ii Copyright By Abigail Elizabeth Martens 2017 i Structural Analysis of Silicic Lava Flow Margins at Obsidian Dome, California by Abigail Martens, B.S. This thesis or project has been accepted on behalf of the Department of Geological Sciences by their supervisory committee: Dr. William C. Krugh Assistant Professor of Geology, California State University, Bakersfield Committee Chair Dr. Anthony Rathburn Professor of Geology, California State University, Bakersfield Committee Member Dr. Graham Douglas Michael Andrews Assistant Professor of Geology, West Virginia University Committee Member 111 Contents List of Tables .................................................................................................................................. v List of Figures ................................................................................................................................ vi Abstract ........................................................................................................................................... 1 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 2 1.1 Models of Silicic Lava Emplacement ..................................................................................