Periodic Behavior in Lava Dome Eruptions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Mineralogical and Geochemical Assessment of the Potential Respiratory Health Hazard of Ash from Sakurajima Volcano, Japan

Durham E-Theses A Mineralogical and Geochemical Assessment of the Potential Respiratory Health Hazard of Ash from Sakurajima Volcano, Japan. HILLMAN, SARAH,ELIZABETH How to cite: HILLMAN, SARAH,ELIZABETH (2010) A Mineralogical and Geochemical Assessment of the Potential Respiratory Health Hazard of Ash from Sakurajima Volcano, Japan., Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/318/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 A Mineralogical and Geochemical Assessment of the Potential Respiratory Health Hazard of Ash from Sakurajima Volcano, Japan. Sarah Elizabeth Hillman Institute of Hazard, Risk and Resilience, Department of Earth Science, Durham University. Thesis submitted for the degree of MSc by Research 2010 i Abstract Sakurajima Volcano, Kyushu Island is the most active volcano in Japan. Vulcanian eruptions have occurred almost constantly since 1955, and it continues to erupt hundreds of times a year, repeatedly affecting local populations and the environment. -

Source to Surface Model of Monogenetic Volcanism: a Critical Review

Downloaded from http://sp.lyellcollection.org/ by guest on September 28, 2021 Source to surface model of monogenetic volcanism: a critical review I. E. M. SMITH1 &K.NE´ METH2* 1School of Environment, University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand 2Volcanic Risk Solutions, Massey University, Palmerston North 4442, New Zealand *Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Small-scale volcanic systems are the most widespread type of volcanism on Earth and occur in all of the main tectonic settings. Most commonly, these systems erupt basaltic magmas within a wide compositional range from strongly silica undersaturated to saturated and oversatu- rated; less commonly, the spectrum includes more siliceous compositions. Small-scale volcanic systems are commonly monogenetic in the sense that they are represented at the Earth’s surface by fields of small volcanoes, each the product of a temporally restricted eruption of a composition- ally distinct batch of magma, and this is in contrast to polygenetic systems characterized by rela- tively large edifices built by multiple eruptions over longer periods of time involving magmas with diverse origins. Eruption styles of small-scale volcanoes range from pyroclastic to effusive, and are strongly controlled by the relative influence of the characteristics of the magmatic system and the surface environment. Gold Open Access: This article is published under the terms of the CC-BY 3.0 license. Small-scale basaltic magmatic systems characteris- hazards associated with eruptions, and this is tically occur at the Earth’s surface as fields of small particularly true where volcanic fields are in close monogenetic volcanoes. These volcanoes are the proximity to population centres. -

Anatomy of a Volcanic Eruption: Case Study: Mt. St. Helens

Anatomy of a Volcanic Eruption: Case Study: Mt. St. Helens Materials Included in this Box: • Teacher Background Information • 3-D models of Mt. St. Helens (before and after eruption) • Examples of stratovolcano rock products: Tuff (pyroclastic flow), pumice, rhyolite/dacite, ash • Sandbox crater formation exercise • Laminated photos/diagrams Teacher Background There are several shapes and types of volcanoes around the world. Some volcanoes occur on the edges of tectonic plates, such as those along the ‘ring of fire’. But there are also volcanoes that occur in the middle of tectonic plates like the Yellowstone volcano and Kilauea volcano in Hawaii. When asked to draw a volcano most people will draw a steeply sided, conical mountain that has a depression (crater) at the top. This image of a 'typical' volcano is called a stratovolcano (a.k.a. composite volcano). While this is the often visualized image of a volcano, there are actually many different shapes volcanoes can be. A volcano's shape is mostly determined by the type of magma/lava that is created underneath it. Stratovolcanoes get their shape because of the thick, sticky (viscous) magma that forms at subduction zones. This magma/lava is layered between ash, pumice, and rock fragments. These layers of ash and magma will build into high elevation, steeply sided, conical shaped mountains and form a 'typical' volcano shape. Stratovolcanoes are also known for their explosive and destructive eruptions. Eruptions can cause clouds of gas, ash, dust, and rock fragments to eject into the atmosphere. These clouds of ash can become so dense and heavy that they quickly fall down the side of the volcanoes as a pyroclastic flow. -

The Science Behind Volcanoes

The Science Behind Volcanoes A volcano is an opening, or rupture, in a planet's surface or crust, which allows hot magma, volcanic ash and gases to escape from the magma chamber below the surface. Volcanoes are generally found where tectonic plates are diverging or converging. A mid-oceanic ridge, for example the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, has examples of volcanoes caused by divergent tectonic plates pulling apart; the Pacific Ring of Fire has examples of volcanoes caused by convergent tectonic plates coming together. By contrast, volcanoes are usually not created where two tectonic plates slide past one another. Volcanoes can also form where there is stretching and thinning of the Earth's crust in the interiors of plates, e.g., in the East African Rift, the Wells Gray-Clearwater volcanic field and the Rio Grande Rift in North America. This type of volcanism falls under the umbrella of "Plate hypothesis" volcanism. Volcanism away from plate boundaries has also been explained as mantle plumes. These so- called "hotspots", for example Hawaii, are postulated to arise from upwelling diapirs with magma from the core–mantle boundary, 3,000 km deep in the Earth. Erupting volcanoes can pose many hazards, not only in the immediate vicinity of the eruption. Volcanic ash can be a threat to aircraft, in particular those with jet engines where ash particles can be melted by the high operating temperature. Large eruptions can affect temperature as ash and droplets of sulfuric acid obscure the sun and cool the Earth's lower atmosphere or troposphere; however, they also absorb heat radiated up from the Earth, thereby warming the stratosphere. -

Disaster Preparedness for Natural Hazards in Japan (Case Studying in Hyogo Prefecture)

Disaster Preparedness for Natural Hazards in Japan (Case Studying in Hyogo Prefecture) By N.P. Madawan Arachchi (Fulfillment of Visiting Researcher Program in Asian Disaster Reduction Center, Kobe, Japan) N.P Madawan Arachchi Visiting Researcher (Aug-Nov2014) ADRC I Acknowledgement First and foremost, I would like to express my sincere gratitude and lots of thanks Mr. Kiyoshi NATORI, Executive Director of ADRC offering me this valuable opportunity to helping member countries to develop the human resource capacity of officers who are involving in disaster risk management activities. Thank you Sir. I would like to offer my sincere thanks Ms. Yumi Shiomi– Senior Researcher of Asian Disaster Reduction Center (ADRC) as coordinator of this program giving valuable service to every time and supporting all the time beyond the expected. She had done a best hospitality during our memorable stay in Japan and fully involved in our research activities during the program. I offer my special thanks Mr. Makoto Ikeda, Mentor, helping me greatly to be success this research program. He helped me giving advice and doing translation which was most difficult task I have faced for finding and delivering information. Sir, I appreciate your valuable service. Further, I offer my gratitude to all staff members of ADRC giving supports and helping me all the time in numerous manners. Specially Senior Researchers, Researchers, Administrative and supporting staffs. I remind your valuable, memorable service giving us during staying in beautiful Japan. An appreciation and best regards to our Japanese Teacher (Sensei) Mr. Shoji Kawahara, being a good talented teacher that always passionate to teach us the Japanese’s language, culture, foods and others important information. -

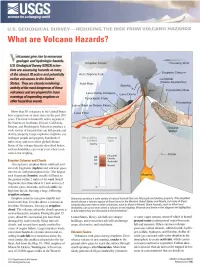

What Are Volcano Hazards?

USGS science for a changing world U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY REDUCING THE RISK FROM VOLCANO HAZARDS What are Volcano Hazards? \7olcanoes give rise to numerous T geologic and hydrologic hazards. Eruption Cloud Prevailing Wind U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) scien tists are assessing hazards at many Eruption Column of the almost 70 active and potentially Ash (Tephra) Fall active volcanoes in the United Landslide (Debris Avalanche) States. They are closely monitoring Acid Rain Bombs activity at the most dangerous of these Pyroclastic Flow volcanoes and are prepared to issue Lava Dome Collapse x Lava Dome warnings of impending eruptions or Pyroclastic Flow other hazardous events. Lahar (Mud or Debris Flow)jX More than 50 volcanoes in the United States Lava Flow have erupted one or more times in the past 200 years. The most volcanically active regions of the Nation are in Alaska, Hawaii, California, Oregon, and Washington. Volcanoes produce a wide variety of hazards that can kill people and destroy property. Large explosive eruptions can endanger people and property hundreds of miles away and even affect global climate. Some of the volcano hazards described below, such as landslides, can occur even when a vol cano is not erupting. Eruption Columns and Clouds An explosive eruption blasts solid and mol ten rock fragments (tephra) and volcanic gases into the air with tremendous force. The largest rock fragments (bombs) usually fall back to the ground within 2 miles of the vent. Small fragments (less than about 0.1 inch across) of volcanic glass, minerals, and rock (ash) rise high into the air, forming a huge, billowing eruption column. -

UAS-Based Tracking of the Santiaguito Lava Dome, Guatemala

Boise State University ScholarWorks Geosciences Faculty Publications and Presentations Department of Geosciences 5-25-2020 UAS-Based Tracking of the Santiaguito Lava Dome, Guatemala Edgar U. Zorn German Research Centre for Geosciences GFZ Thomas R. Walter German Research Centre for Geosciences GFZ Jeffrey B. Johnson Boise State University René Mania German Research Centre for Geosciences GFZ Publication Information Zorn, Edgar U.; Walter, Thomas R.; Johnson, Jeffrey B.; and Mania, René. (2020). "UAS-Based Tracking of the Santiaguito Lava Dome, Guatemala". Scientific Reports, 10, 8644-1 - 8644-13. https://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/s41598-020-65386-2 www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN UAS-based tracking of the Santiaguito Lava Dome, Guatemala Edgar U. Zorn1 ✉ , Thomas R. Walter1, Jefrey B. Johnson2 & René Mania1 Imaging growing lava domes has remained a great challenge in volcanology due to their inaccessibility and the severe hazard of collapse or explosion. Changes in surface movement, temperature, or lava viscosity are considered crucial data for hazard assessments at active lava domes and thus valuable study targets. Here, we present results from a series of repeated survey fights with both optical and thermal cameras at the Caliente lava dome, part of the Santiaguito complex at Santa Maria volcano, Guatemala, using an Unoccupied Aircraft System (UAS) to create topography data and orthophotos of the lava dome. This enabled us to track pixel-ofsets and delineate the 2D displacement feld, strain components, extrusion rate, and apparent lava viscosity. We fnd that the lava dome displays motions on two separate timescales, (i) slow radial expansion and growth of the dome and (ii) a narrow and fast- moving lava extrusion. -

Preservation of Disaster Monuments for Tourism and Education in Mount Unzen

Journal of Geodesy and Geomatics Engineering 2 (2016) 18-23 D doi: 10.17265/2332-8223/2016.02.003 DAVID PUBLISHING Preservation of Disaster Monuments for Tourism and Education in Mount Unzen Shin’ichi Sugimoto1, and Chiharu Hayashi2 1. Regional Policy Research Center, Iwate Prefectural University, Iwate, 020-0693, Japan 2. Sanriku Geopark Promotion Committee, Iwate, 027-0072, Japan Abstract: The territory of the Shimabara Peninsula could recover steadily from volcanic disasters associated with the eruption at Unzen during 1991-1995. The disasters and the recovery brought various lessons, related to responses to volcanic eruptions and hazards, support system for people impacted by the disasters and the method for socioeconomic recovery. After the eruption, education facilities to learn volcanic eruptions and disasters, such as the Mount Unzen Disaster Memorial Hall, were prepared, as well as scientific projects to clarify eruption mechanisms were carried out. Under these circumstances, holding two international conferences were invited. The 5th Cities on Volcanoes Conference and the 5th International UNESCO Conference on Geoparks were held in Shimabara in 2007 and 2012, respectively. Under these circumstances, holding two international conferences were invited. On the process that local people recovered from the disasters, the communities carried out disaster-prevention education and volcano tourism, utilizing the Mount Unzen Disaster Memorial Hall and the park of houses buried by mudflow deposits. The memorial hall archives valuable materials of the disasters and provides simulations of volcanic eruptions with the newest technology, by which visitors can learn about volcanic eruptions. Disaster remains, such as the memorial hall and park, are effective for visitors who did not experience volcanic disasters and are difficult to imagine the real volcanic hazard. -

1998 Volcanic Activity in Alaska and Kamchatka: Summary of Events and Response of the Alaska Volcano Observatory by Robert G

1998 Volcanic Activity in Alaska and Kamchatka: Summary of Events and Response of the Alaska Volcano Observatory by Robert G. McGimsey, Christina A. Neal, and Olga Girina Open-File Report 03-423 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey 1998 Volcanic Activity in Alaska and Kamchatka: Summary of Events and Response of the Alaska Volcano Observatory By Robert G. McGimsey1, Christina A. Neal1, and Olga Girina2 1Alaska Volcano Observatory, 4200 University Dr., Anchorage, AK 99508-4664 2Kamchatka Volcanic eruptions Response Team, Institute of Volcanic Geology and Geochemistry, Piip Blvd., 9 Petropavlovsk-Kam- chatsky, 683006, Russia AVO is a cooperative program of the U.S. Geological Survey, University of Alaska Fairbanks Geophysical Institute, and the Alaska Division of Geological and Geophysical Surveys. AVO is funded by the U.S. Geological Survey Volcano Hazards Program and the State of Alaska Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government Open-File Report 03-423 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction. 1 Reports of volcanic activity, northeast to southwest along Aleutian arc . 4 Shrub Mud Volcano . 4 Augustine Volcano . 6 Becharof Lake Area . 8 Chiginagak Volcano . 10 Shishaldin Volcano. 12 Akutan Volcano . 12 Korovin Volcano . 13 Reports of Volcanic activity, Kamchatka, Russia, North to South . 15 Sheveluch Volcano . 17 Klyuchevskoy Volcano. 19 Bezymianny Volcano . 21 Karymsky Volcano . 23 References. 24 Acknowledgments . 26 Figures 1 A. Map location of historically active volcanoes in Alaska and place names used in this summary . -

Structural Analysis of Silicic Lava Flow Margins at Obsidian Dome, California

Structural Analysis of Silicic Lava Flow Margins at Obsidian Dome, California by Abigail Martens, B.S. A Thesis Submitted to the Department of Geological Sciences California State University Bakersfield In Partial Fulfillment for the Degree of Masters of Geology Spring 2017 ii Copyright By Abigail Elizabeth Martens 2017 i Structural Analysis of Silicic Lava Flow Margins at Obsidian Dome, California by Abigail Martens, B.S. This thesis or project has been accepted on behalf of the Department of Geological Sciences by their supervisory committee: Dr. William C. Krugh Assistant Professor of Geology, California State University, Bakersfield Committee Chair Dr. Anthony Rathburn Professor of Geology, California State University, Bakersfield Committee Member Dr. Graham Douglas Michael Andrews Assistant Professor of Geology, West Virginia University Committee Member 111 Contents List of Tables .................................................................................................................................. v List of Figures ................................................................................................................................ vi Abstract ........................................................................................................................................... 1 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 2 1.1 Models of Silicic Lava Emplacement .................................................................................. -

Cerro Pizarro Volcano, Mexico by G. Carrasco-Nú

1 Polygenetic nature of a rhyolitic dome and implications for hazard assessment: 2 Cerro Pizarro volcano, Mexico 3 by G. Carrasco-Núñez and N. Riggs 4 5 ABSTRACT 6 Rhyolitic domes are commonly regarded as monogenetic volcanoes associated with single, brief 7 eruptions. They are characterized by short-lived successions of pyroclastic and effusive activity 8 associated with a series of discrete eruptive events that apparently last on the order of years to 9 decades. Cerro Pizarro, a ~ 1.1 km3 rhyolitic dome in the eastern Mexican Volcanic Belt, shows 10 aspects of polygenetic volcanism including long-term repose periods (~ 50-80 ky) between 11 eruptions, chemical variations with time, and a complex evolution of alternating explosive and 12 effusive eruptions, a cryptodome phase, and sector collapse. This eruptive behavior provides 13 new insights into how rhyolite domes may evolve. A protracted, complex evolution bears 14 important implications for hazard assessment if reactivation of an apparently extinct rhyolitic 15 dome must be seriously considered. 16 17 Keywords: monogenetic volcanism, polygenetic volcanism, rhyolites, dome growth, volcanic 18 hazards, Mexican Volcanic Belt 19 20 INTRODUCTION 21 Monogenetic volcanoes comprise a wide spectrum of relatively small volcanic structures 22 (generally less than a few km3 erupted material) that show a commonly simple evolution (one 23 eruption, or a few clearly related eruptions), short life span (commonly years to decades for 24 mafic volcanoes, but possibly as much as a few centuries for rhyolitic domes), and minor 25 chemical composition changes. Monogenetic volcanoes are, in general, either basalt or rhyolite, 26 while polygenetic volcanoes, which erupt repeatedly and have a large and persistent magma 27 storage chamber, are commonly andesitic or dacitic in composition. -

Flood Basalt Shield Cinder Cone Stratovolcano Lava Dome Mid

Volcano Mid-Ocean Flood Basalt Shield Cinder Cone Stratovolcano Lava Dome Caldera Review Table Ridge small, steep-sided low, broad mountain small mountain, large, steep-sided large depressions extensive plateaus o rift valley o mountain, Landform with slopes <5 , 20-30 slopes, mountain, 10's of km wide up to 9,000-m high up to 400-m high up to 3,000-m high up to ~500-m high Eruption huge volumes of lava lava >> tephra pillow lava tephra >> lava tephra + lava lava > tephra tephra >> lava Products (105 to 106 km3) Magma mafic mafic mafic felsic felsic Composition mafic intermediate Magma low low low low moderate high high Viscosity % Gas in Magma low low low moderate low to high low to high low to high Eruption high discharge rate point source & fissure small eruption column, large eruption column, dome collapse, multiple fissure-fed submarine flows from multiple fissures "fire" fountains fire fountain pyroclastic flows pyroclastic flows pyroclastic flows Style (Hawaiian) (Strombolian) (Plinian) (Pelean) (ultra-Plinian) Explosivity low low low low-moderate very high high ultra-high hydrous (wet) Magma mantle mantle mantle mantle crust/mantle crustal melting crustal melting partial melting partial melting partial melting partial melting Origin melting Plate Tectonic "hot spot" Oceanic Convergent margin numerous numerous numerous numerous Setting (mantle plume) divergent margin (subduction zone) Columbia River, Mid-Atlantic Ridge, Paricutin, Mt. St. Helens, Mt. Unzen, Valles, Long Valley, Mauna Loa, Kilaeua, Examples Deccan Traps, East Pacific