A Study of the Naths of West Bengal and Assam Author(S): Kunal Debnath Source: Explorations, ISS E-Journal, Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

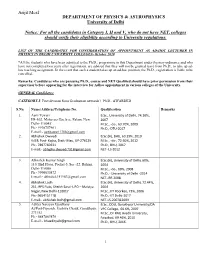

Arijit Mcaf DEPARTMENT of PHYSICS & ASTROPHYSICS

Arijit Mcaf DEPARTMENT OF PHYSICS & ASTROPHYSICS University of Delhi Notice: For all the candidates in Category I, II and V, who do not have NET, colleges should verify their eligibility according to University regulations. LIST OF THE CANDIDATES FOR CONSIDERATION OF APPOINTMENT AS AD-HOC LECTURER IN PHYSICS IN DELHI UNIVERSITY COLLEGES- October 2020 *All the students who have been admitted to the Ph.D., programme in this Department under the new ordinance and who have not completed two years after registration, are advised that they will not be granted leave from Ph.D., to take up ad- hoc teaching assignment. In the event that such a student takes up an ad-hoc position, the Ph.D., registration is liable to be cancelled. Remarks: Candidates who are pursuing Ph.D., course and NET Qualified should have prior permission from their supervisor before appearing for the interview for Adhoc appointment in various colleges of the University. GENERAL Candidates: CATEGORY-I: First division from Graduation onwards + Ph.D., AWARDED S.No. Name/Address/Telephone No. Qualification Remarks 1. Aarti Tewari B.Sc., University of Delhi, 74.10%, H4-102, Mahaveer Enclave, Palam, New 2007 Delhi-110045` M.Sc., -do-, 63.70%, 2009 Ph:- 9910757461 Ph.D.,-DTU-2017 E-mail:- [email protected] 2. Abhishek Dwivedi B.Sc.(H), BHU, 60.39%, 2010 Vill & Post- Kajha, Distt- Mau, UP-276129 M.Sc., -do-, 72.60%, 2012 Ph:- 7897760331 Ph.D., BHU, 2017 E-mail:- [email protected] NET- LS-2012 3. Abhishek Kumar Singh B.Sc.(H), University of Delhi, 60%, 110, IInd Floor, Pocket-5, Sec.-22, Rohini, 2004 Delhi-110086 M.Sc., -do-, 60%, 2008 Ph:- 9990030872 Ph.D.,- University of Delhi -2014 E-mail:- [email protected] NET-JRF-2008 4. -

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email Id Remarks 9421864344 022 25401313 / 9869262391 Bhaveshwarikar

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email id Remarks 10001 SALPHALE VITTHAL AT POST UMARI (MOTHI) TAL.DIST- Male DEFAULTER SHANKARRAO AKOLA NAME REMOVED 444302 AKOLA MAHARASHTRA 10002 JAGGI RAMANJIT KAUR J.S.JAGGI, GOVIND NAGAR, Male DEFAULTER JASWANT SINGH RAJAPETH, NAME REMOVED AMRAVATI MAHARASHTRA 10003 BAVISKAR DILIP VITHALRAO PLOT NO.2-B, SHIVNAGAR, Male DEFAULTER NR.SHARDA CHOWK, BVS STOP, NAME REMOVED SANGAM TALKIES, NAGPUR MAHARASHTRA 10004 SOMANI VINODKUMAR MAIN ROAD, MANWATH Male 9421864344 RENEWAL UP TO 2018 GOPIKISHAN 431505 PARBHANI Maharashtra 10005 KARMALKAR BHAVESHVARI 11, BHARAT SADAN, 2 ND FLOOR, Female 022 25401313 / bhaveshwarikarmalka@gma NOT RENEW RAVINDRA S.V.ROAD, NAUPADA, THANE 9869262391 il.com (WEST) 400602 THANE Maharashtra 10006 NIRMALKAR DEVENDRA AT- MAREGAON, PO / TA- Male 9423652964 RENEWAL UP TO 2018 VIRUPAKSH MAREGAON, 445303 YAVATMAL Maharashtra 10007 PATIL PREMCHANDRA PATIPURA, WARD NO.18, Male DEFAULTER BHALCHANDRA NAME REMOVED 445001 YAVATMAL MAHARASHTRA 10008 KHAN ALIMKHAN SUJATKHAN AT-PO- LADKHED TA- DARWHA Male 9763175228 NOT RENEW 445208 YAVATMAL Maharashtra 10009 DHANGAWHAL PLINTH HOUSE, 4/A, DHARTI Male 9422288171 RENEWAL UP TO 05/06/2018 SUBHASHKUMAR KHANDU COLONY, NR.G.T.P.STOP, DEOPUR AGRA RD. 424005 DHULE Maharashtra 10010 PATIL SURENDRANATH A/P - PALE KHO. TAL - KALWAN Male 02592 248013 / NOT RENEW DHARMARAJ 9423481207 NASIK Maharashtra 10011 DHANGE PARVEZ ABBAS GREEN ACE RESIDENCY, FLT NO Male 9890207717 RENEWAL UP TO 05/06/2018 402, PLOT NO 73/3, 74/3 SEC- 27, SEAWOODS, -

Camscanner 07-06-2020 17.45.18

ftyk xzkeh.k fodkl vfHkdj.k] gtkjhckxA rduhfd lgk;d ¼lgk;d vfHk;ark ds led{k½ ds fjDr in ij fu;qfDr gsrq izkIr vkosnuksa dh izkjafHkd lwph ESSENTIAL QUALIFICATION ADDITIONAL QUALIFICATION OTHER CASTE AFFID B.E./ B.TECH IN CIVIL M.TECH/ P.G.D.C.A./ M.C.A/ MCA MARKS SL. STATE/ CERTIFI AVIT NAME F/H NAME SEX PERMANENT ADDRESS PRESENT ADDRESS D.O.B. CATG. AFTER 5 EXP. REMARKS NO. DISTRI CATE (YES/ TOTAL OBTAINE TOTAL OBTAINE POINTS CT (Y/N) COURSE % GE COURSE % GE NO) MARKS D MARKS MARKS D MARKS LESS 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18PGDCA 19 20 21 22 VILLAGE-JARA TOLA, VILLAGE- SOLIYA, PO- B.E. IN MARKSHEE AVINASH LATE NARESH MURRAMKALA, PO PALANI, TALATAND, PS- 1 Male Y 25-11-1995 ST Y CIVIL N N T NOT MUNDA MUNDA +PS+DISTRICT-RAMGARH PATRATU, DISTRICT- ENGG. ATTACHED. 829122 Jharkhand Ramgarh 829119 Jharkhand G.R. HOUSE, SIR SYED G.R. HOUSE, SIR SYED NAGAR, KAJLAMANI ROAD, NAGAR, KAJLAMANI ROAD, B.E. IN MARKSHEE MD GAZNAFER JAMIL AKHTER KISHANGANJ, KISHANGANJ KISHANGANJ, KISHANGANJ 2 Male Y 01-05-1991 GEN - CIVIL N Y T NOT RABBANI RABBANI TOWN, TOWN, ENGG. ATTACHED. PS+BLOCK+DISTRICT- PS+BLOCK+DISTRICT- KISHANGANJ 855107 Bihar KISHANGANJ 855107 Bihar VILL- AMBAKOTHI, VILL- AMBAKOTHI, B.E. IN PRAMOD 3 SURESH RAM Male PO+PS+BLOCK+DISTRICT- PO+PS+BLOCK+DISTRICT- Y 20-03-1982 SC Y CIVIL 8000 5144 64.30 N Y KUMAR LATEHAR 829206 Jharkhand LATEHAR 829206 Jharkhand ENGG. -

Ethnological and Legal Study of Jogis

Academic Research Publishing Group The Journal of Social Sciences Research ISSN(e): 2411-9458, ISSN(p): 2413-6670 Vol. 2, No. 3, pp: 48-53, 2016 URL: http://arpgweb.com/?ic=journal&journal=7&info=aims Ethnological and Legal Study of Jogis Vaibhav Jain BBA-LLB (Hons.) Scholar, The Institute of Chartered Financial Analysts of India (ICFAI) University Dehradun – 248197, India Abstract: This paper deals with a community of Jogis which is fighting for its survival in all phases and in each place (country). They are found in major religions but undeveloped and considered to be of low social status in all subcontinents and are victim of society. This community did that type of work for their livelihood which no other community does but they do it for their survival and livelihood. In this paper I throw the light upon the present living conditions and origin of Jogis in Afghanistan and their connections with Jogis of Jain origin these both communities are very petite in number now and the Jogis of Jain origin are may be now fully extinct. Keywords: Jogis; Jainism; Gorakhnath; Afghanistan; Tazkira(citizenship proof); Punjab; Rawal. 1. Introduction The Jogis as a community cannot be said to have any history; there are many branches into which they are split ranging from all Indian subcontinent (including Afghanistan) and pursuing various religions and different way of life. In many reports of UN there are disambiguate that Jogis came from Central Asia (Zahir, 2012) or of Jat origin (Samuel Hall Consulting, 2011),they are of a bigger ethnic group of Jogis which are of indegenious origin, they have a great past and culture they are basically followers of Gorakhnath or of his disciple, so they still live and uses customary beliefs and follow native culture. -

Bhakti Movement

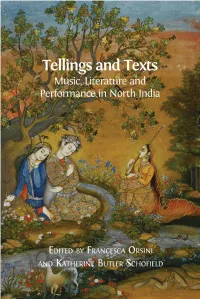

TELLINGS AND TEXTS Tellings and Texts Music, Literature and Performance in North India Edited by Francesca Orsini and Katherine Butler Schofield http://www.openbookpublishers.com © Francesca Orsini and Katherine Butler Schofield. Copyright of individual chapters is maintained by the chapters’ authors. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work; to adapt the work and to make commercial use of the work providing attribution is made to the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: Orsini, Francesca and Butler Schofield, Katherine (eds.), Tellings and Texts: Music, Literature and Performance in North India. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0062 Further details about CC BY licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by/4.0/ In order to access detailed and updated information on the license, please visit: http://www.openbookpublishers.com/isbn/9781783741021#copyright All external links were active on 22/09/2015 and archived via the Internet Archive Wayback Machine: https://archive.org/web/ Digital material and resources associated with this volume are available at http:// www.openbookpublishers.com/isbn/9781783741021#resources ISBN Paperback: 978-1-78374-102-1 ISBN Hardback: 978-1-78374-103-8 ISBN Digital (PDF): 978-1-78374-104-5 ISBN Digital ebook (epub): 978-1-78374-105-2 ISBN Digital ebook (mobi): 9978-1-78374-106-9 DOI: 10.11647/OBP.0062 King’s College London has generously contributed to the publication of this volume. -

1 CENTRAL LIST of Obcs for the STATE of HARYANA Entry No Caste

CENTRAL LIST OF OBCs FOR THE STATE OF HARYANA Entry No Caste/ Community Resolution No. & Date Aheria 12011/68/93-BCC(C) dt. 10/09/1993 Aheri 12015/2/2007-BCC dt. 18/08/2010 Hari 1. Heri Naik Theri or Turi or Thori 2. Barra 12011/68/93-BCC(C) dt. 10/09/1993 Beta 12011/68/93-BCC(C) dt. 10/09/1993 3. Hensi or Hesi 4. Bagria or Bagaria 12011/68/93-BCC(C) dt. 10/09/1993 5. Barwar 12011/68/93-BCC(C) dt. 10/09/1993 Barai 12011/68/93-BCC(C) dt. 10/09/1993 6. Tamboli Baragi 12011/68/93-BCC(C) dt. 10/09/1993 7. Bairagi 8. Battera 12011/68/93-BCC(C) dt. 10/09/1993 Bharbhunja 12011/68/93-BCC(C) dt. 10/09/1993 9. Bharbhuja Bhat 12011/68/93-BCC(C) dt. 10/09/1993 Bhatra 10. Darpi Ramiya 11. Bhuhalia Lohar 12011/68/93-BCC(C) dt. 10/09/1993 12. Changar 12011/68/93-BCC(C) dt. 10/09/1993 13. Chirimar 12011/68/93-BCC(C) dt. 10/09/1993 14. Chang 12011/68/93-BCC(C) dt. 10/09/1993 Chimba or Chhimba, 12011/68/93-BCC(C) dt. 10/09/1993 Chhipi, 12011/44/99-BCCdt. 21/09/2000 15. Chimpa, Darzi, Rohilla 16. Daiya 12011/68/93-BCC(C) dt. 10/09/1993 17. Dhobi 12011/68/93-BCC(C) dt. 10/09/1993 18. Dakaut 12011/68/93-BCC(C) dt. 10/09/1993 Dhimar, 12011/68/93-BCC(C) dt. -

Folklore, Orality and Tradition

Chapter-1 Introduction: Folklore, Orality and Tradition The study of folklore is inclusive of many different disciplines that overlap and intermingle with each other. Disciplines like anthropology, psychology, sociology, literary studies and women’s studies, linguistics, all come together to study the folklore in wider terms. It becomes essential to understand and analyse folk literature in the light of above disciplines to get a better understanding of the culture and history behind the given oral literature. Folklore surpasses boundaries of time in a way that it brings the culture and civilization of the past and merges it with the future for a better understanding. It continuously flows with the civilization by adopting different forms on the course of its journey. That way, it never gets struck in one time. It is not a static thing to be stored and preserved in any one form which struts itself as the ‘original. It is continuously and spontaneously being produced by the people who are blissfully ignorant of its various facets and its profound effect on the modern civilization. It is no more a thing of the rural or semi-urban masses but it is very much a part of the modern world. Many attempts have been made to define, categorize and theorize the term ‘folklore’ through words that can give it a concrete meaning. Folklore does not only include what is passed orally from one generation to another rather it encompasses everything including the cultural norms, behavioral codes, individual identities, feelings and emotions, religious beliefs, and experiences of not only a particular race or nationality but also of each individual living through it. -

Mughal Paintings (16Th – 19Th Century)

UNIT - III PERFORMING ARTS • Performing arts refers to forms of art in which artists use their voices, bodies or inanimate objects to convey artistic expression. It is different from visual arts, which is when artists use paint, canvas or various materials to create physical or static art objects. • Performing arts include a range of disciplines which are performed in front of a live audience, inducing theatre, music, and dance INDIAN MUSIC • Owing to India's vastness and diversity, Indian Music encompass numerous genres, multiple varieties and forms which include classical music, folk music, filmi, rock, and pop. It has a history spanning several millennia and developed over several geo- locations spanning the sub-continent. • Hindustani Classical Music: Indian classical music found throughout North India. The style is sometimes called North Indian classical music or Shāstriya Sangīt. It is a tradition that originated in Vedic ritual chants and has been evolving since the 12th century CE, in North India and to some extent in Nepal and Afghanistan. • Carnatic music (Karnataka Sangita): A system of music commonly associated with the southern part of the Indian subcontinent, with its area roughly confined to four modern states of India: Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Kerala, and Tamil Nadu. • It is one of two main sub-genres of Indian classical music that evolved from ancient Hindu traditions; the other sub-genre being Hindustani music, which emerged as a distinct form because of Persian and Islamic influences in North India. FOLK MUSIC IN INDIA Introduction The music of common people, farmers, village occupational, masses adorned with beautiful simple lyrics and rhythms, interesting poetry depicting nature and human mind. -

Annexure V - Caste Codes State Wise List of Castes

ANNEXURE V - CASTE CODES STATE WISE LIST OF CASTES STATE TAMIL NADU CODE CASTE 1 ADDI DIRVISA 2 AKAMOW DOOR 3 AMBACAM 4 AMBALAM 5 AMBALM 6 ASARI 7 ASARI 8 ASOOY 9 ASRAI 10 B.C. 11 BARBER/NAI 12 CHEETAMDR 13 CHELTIAN 14 CHETIAR 15 CHETTIAR 16 CRISTAN 17 DADA ACHI 18 DEYAR 19 DHOBY 20 DILAI 21 F.C. 22 GOMOLU 23 GOUNDEL 24 HARIAGENS 25 IYAR 26 KADAMBRAM 27 KALLAR 28 KAMALAR 29 KANDYADR 30 KIRISHMAM VAHAJ 31 KONAR 32 KONAVAR 33 M.B.C. 34 MANIGAICR 35 MOOPPAR 36 MUDDIM 37 MUNALIAR 38 MUSLIM/SAYD 39 NADAR 40 NAIDU 41 NANDA 42 NAVEETHM 43 NAYAR 44 OTHEI 45 PADAIACHI 46 PADAYCHI 47 PAINGAM 48 PALLAI 49 PANTARAM 50 PARAIYAR 51 PARMYIAR 52 PILLAI 53 PILLAIMOR 54 POLLAR 55 PR/SC 56 REDDY 57 S.C. 58 SACHIYAR 59 SC/PL 60 SCHEDULE CASTE 61 SCHTLEAR 62 SERVA 63 SOWRSTRA 64 ST 65 THEVAR 66 THEVAR 67 TSHIMA MIAR 68 UMBLAR 69 VALLALAM 70 VAN NAIR 71 VELALAR 72 VELLAR 73 YADEV 1 STATE WISE LIST OF CASTES STATE MADHYA PRADESH CODE CASTE 1 ADIWARI 2 AHIR 3 ANJARI 4 BABA 5 BADAI (KHATI, CARPENTER) 6 BAMAM 7 BANGALI 8 BANIA 9 BANJARA 10 BANJI 11 BASADE 12 BASOD 13 BHAINA 14 BHARUD 15 BHIL 16 BHUNJWA 17 BRAHMIN 18 CHAMAN 19 CHAWHAN 20 CHIPA 21 DARJI (TAILOR) 22 DHANVAR 23 DHIMER 24 DHOBI 25 DHOBI (WASHERMAN) 26 GADA 27 GADARIA 28 GAHATRA 29 GARA 30 GOAD 31 GUJAR 32 GUPTA 33 GUVATI 34 HARJAN 35 JAIN 36 JAISWAL 37 JASODI 38 JHHIMMER 39 JULAHA 40 KACHHI 41 KAHAR 42 KAHI 43 KALAR 44 KALI 45 KALRA 46 KANOJIA 47 KATNATAM 48 KEWAMKAT 49 KEWET 50 KOL 51 KSHTRIYA 52 KUMBHI 53 KUMHAR (POTTER) 54 KUMRAWAT 55 KUNVAL 56 KURMA 57 KURMI 58 KUSHWAHA 59 LODHI 60 LULAR 61 MAJHE -

Maria Angelillo University of Milan Italy RETHINKING RESOURCES

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by AIR Universita degli studi di Milano Maria Angelillo University of Milan Italy RETHINKING RESOURCES: SERVICE NOMADISM ADJUSTED UDC 316.7:314.63(540) Abstract This article is based on six years fieldwork with Kalbelia community living in the environs of Pushkar, a famous place of pilgrimage, tīrtha, for Hindus and a popular tourist destination, especially for foreigner backpacker travelers, situated at the edge of the Thar desert and at the foot at the outer fringes of the Aravalli mountain chain, at the centre of the western state of Rajasthan. It will be explained how Kalbelias’ traditional means of living describe a form of economic, social and cultural adaptation common to groups defined both as service nomads and as peripatetic peoples. The purpose of the present article is to show that both the definitions fit not only the past identity of Kalbelias as wandering snake charmers, but they can be still effective in describing the present of the caste and its new emerging working profile as folk dancers and musicians. It will be argued in fact that, even if in the past few years the meaning and the content of Kalbelia service nomadism have been going through a deep transformation which can be considered to be mainly a creative answer to a whole string of significant social changes occurring in Indian and Rajasthani society, Kalbelias’ new occupational profile entails new forms of spatial mobility. If spatial mobility is proving to be a meaningless economic strategy as far as snake charming and begging is concerned, it is in fact yet highly effective with regard to the new professional identity of the caste. -

Yogi Heroes and Poets

Lorenzen_Yogi:SUNY 6 x 9 9/8/11 3:47 PM Page ix introduction David N. Lorenzen and Adrián Muñoz all disciples sleep, but the nath satguru stays full awake. the avadhuta begs for alms at the ten gates. —gorakh bānī pad 53 he Hindu religious path or sect of the naths is variously known as the nath tPanth or the nath sampraday. its followers are called nath yogis, nath Pan- this, Kanphata yogis, gorakhnathis, and siddha yogis, among other names. some- times the term avadhūta is used, although this term is applied to ascetics of other Hindu groups as well. Most nath yogis claim adherence to the teachings of the early yogi, gorakִsanātha (in Hindi gorakhnath). the school of yoga most closely associated with the naths is the well-known one of hatִha yoga. in more general terms, the combined religious and yogic teachings of the naths are called the Nāth- mārga (the Path of the naths), the Yoga-mārga (the Path of yoga), or the Siddha- mata (the doctrine of the siddhas). the term siddha means “someone perfected or who has attained [spiritual] per- fection.” a siddha (from the sanskrit root SIDh, “to succeed, to perfect”) is an ascetic who has gained different perfections or “successes” (siddhis), the most famous being the eight magical siddhis achieved through intense yogic practice. the word nāth or nātha literally means “lord, master; protector, shelter,” and in the pres- ent context designates, on the one hand, a follower of the sect founded by or associ- ated with gorakhnath and, on the other hand, someone who has controlled the ix © 2011 State University of New York Press, Albany Lorenzen_Yogi:SUNY 6 x 9 9/8/11 3:47 PM Page x x daVid n. -

Annexure 1B 18416

Annexure 1 B List of taxpayers allotted to State having turnover of more than or equal to 1.5 Crore Sl.No Taxpayers Name GSTIN 1 BROTHERS OF ST.GABRIEL EDUCATION SOCIETY 36AAAAB0175C1ZE 2 BALAJI BEEDI PRODUCERS PRODUCTIVE INDUSTRIAL COOPERATIVE SOCIETY LIMITED 36AAAAB7475M1ZC 3 CENTRAL POWER RESEARCH INSTITUTE 36AAAAC0268P1ZK 4 CO OPERATIVE ELECTRIC SUPPLY SOCIETY LTD 36AAAAC0346G1Z8 5 CENTRE FOR MATERIALS FOR ELECTRONIC TECHNOLOGY 36AAAAC0801E1ZK 6 CYBER SPAZIO OWNERS WELFARE ASSOCIATION 36AAAAC5706G1Z2 7 DHANALAXMI DHANYA VITHANA RAITHU PARASPARA SAHAKARA PARIMITHA SANGHAM 36AAAAD2220N1ZZ 8 DSRB ASSOCIATES 36AAAAD7272Q1Z7 9 D S R EDUCATIONAL SOCIETY 36AAAAD7497D1ZN 10 DIRECTOR SAINIK WELFARE 36AAAAD9115E1Z2 11 GIRIJAN PRIMARY COOPE MARKETING SOCIETY LIMITED ADILABAD 36AAAAG4299E1ZO 12 GIRIJAN PRIMARY CO OP MARKETING SOCIETY LTD UTNOOR 36AAAAG4426D1Z5 13 GIRIJANA PRIMARY CO-OPERATIVE MARKETING SOCIETY LIMITED VENKATAPURAM 36AAAAG5461E1ZY 14 GANGA HITECH CITY 2 SOCIETY 36AAAAG6290R1Z2 15 GSK - VISHWA (JV) 36AAAAG8669E1ZI 16 HASSAN CO OPERATIVE MILK PRODUCERS SOCIETIES UNION LTD 36AAAAH0229B1ZF 17 HCC SEW MEIL JOINT VENTURE 36AAAAH3286Q1Z5 18 INDIAN FARMERS FERTILISER COOPERATIVE LIMITED 36AAAAI0050M1ZW 19 INDU FORTUNE FIELDS GARDENIA APARTMENT OWNERS ASSOCIATION 36AAAAI4338L1ZJ 20 INDUR INTIDEEPAM MUTUAL AIDED CO-OP THRIFT/CREDIT SOC FEDERATION LIMITED 36AAAAI5080P1ZA 21 INSURANCE INFORMATION BUREAU OF INDIA 36AAAAI6771M1Z8 22 INSTITUTE OF DEFENCE SCIENTISTS AND TECHNOLOGISTS 36AAAAI7233A1Z6 23 KARNATAKA CO-OPERATIVE MILK PRODUCER\S FEDERATION