Copyright by Emilia Bachrach 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

In the Name of Krishna: the Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town

In the Name of Krishna: The Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Sugata Ray IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Frederick M. Asher, Advisor April 2012 © Sugata Ray 2012 Acknowledgements They say writing a dissertation is a lonely and arduous task. But, I am fortunate to have found friends, colleagues, and mentors who have inspired me to make this laborious task far from arduous. It was Frederick M. Asher, my advisor, who inspired me to turn to places where art historians do not usually venture. The temple city of Khajuraho is not just the exquisite 11th-century temples at the site. Rather, the 11th-century temples are part of a larger visuality that extends to contemporary civic monuments in the city center, Rick suggested in the first class that I took with him. I learnt to move across time and space. To understand modern Vrindavan, one would have to look at its Mughal past; to understand temple architecture, one would have to look for rebellions in the colonial archive. Catherine B. Asher gave me the gift of the Mughal world – a world that I only barely knew before I met her. Today, I speak of the Islamicate world of colonial Vrindavan. Cathy walked me through Mughal mosques, tombs, and gardens on many cold wintry days in Minneapolis and on a hot summer day in Sasaram, Bihar. The Islamicate Krishna in my dissertation thus came into being. -

Kīrtan Guide Pocket Edition

All glory to Śrī Guru and Śrī Gaurāṅga Kīrtan Guide Pocket Edition Śrī Chaitanya Sāraswat Maṭh All glory to Śrī Guru and Śrī Gaurāṅga Kīrtan Guide Pocket Edition Śrī Chaitanya Sāraswat Maṭh ©&'() Sri Chaitanya Saraswat Math All rights reserved by The Current President-Acharya of Sri Chaitanya Saraswat Math Published by Sri Chaitanya Saraswat Math Kolerganj, Nabadwip, Nadia Pin *+()'&, W.B., India Compiled by Sripad Bhakti Kamal Tyagi Maharaj Senior Editor Sripad Mahananda Das Bhakti Ranjan Editor Sri Vishakha Devi Dasi Brahmacharini Proofreading by Sriman Sudarshan Das Adhikari Sriman Krishna Prema Das Adhikari Sri Asha Purna Devi Dasi Cover by Sri Mahamantra Das Printed by CDC Printers +, Radhanath Chowdury Road Kolkata-*'' '(, First printing: +,''' copies Contents Jay Dhvani . , Ārati . Parikramā . &/ Vandanā . ). Morning . +, Evening . ,+ Vaiṣṇava . ,. Nitāi . 2, Gaurāṅga . *& Kṛṣṇa . .* Prayers . (', Advice . ((/ Śrī Śrī Prabhupāda-padma Stavakaḥ . ()& Śrī Śrī Prema-dhāma-deva Stotram . ()2 Holy Days . (+/ Style . (2* Śrī Chaitanya Sāraswat Maṭh . (*. Index . (*/ Dedication This abridged, pocket size edition of Śrī Chaitanya Sāraswat Maṭh’s Kīrtan Guide was offered to the lotus hands of Śrīla Bhakti Nirmal Āchārya Mahārāj on the Adhivās of the Śrī Nabadwīp Dhām Parikramā Festival, && March &'(). , Jay Dhvani Jay Saparikar Śrī Śrī Guru Gaurāṅga Gāndharvā Govindasundar Jīu kī jay! $%&"'( Jay Om Viṣṇupād Paramahaṁsa Parivrājakāchārya-varya Aṣṭottara-śata-śrī Śrīmad Bhakti Nirmal Āchārya Mahārāj !"# kī jay! Jay Om Viṣṇupād Paramahaṁsa -

The Rich Heritage of Dhrupad Sangeet in Pushtimarg On

Copyright © 2006 www.vallabhkankroli.org - All Rights Reserved by Shree Vakpati Foundation - Baroda ||Shree DwaDwarrrrkeshokesho Jayati|| || Shree Vallabhadhish Vijayate || The Rich Heritage Of Dhrupad Sangeet in Pushtimarg on www.vallabhkankroli.org Reference : 8th Year Text Book of Pushtimargiya Patrachaar by Shree Vakpati Foundation - Baroda Inspiration: PPG 108 Shree Vrajeshkumar Maharajshri - Kankroli PPG 108 Shree Vagishkumar Bawashri - Kankroli Copyright © 2006 www.vallabhkankroli.org - All Rights Reserved by Shree Vakpati Foundation - Baroda Contents Meaning of Sangeet ........................................................................................................................... 4 Naad, Shruti and Swar ....................................................................................................................... 4 Definition of Raga.............................................................................................................................. 5 Rules for Defining Ragas................................................................................................................... 6 The Defining Elements in the Raga................................................................................................... 7 Vadi, Samvadi, Anuvadi, Vivadi [ Sonant, Consonant, Assonant, Dissonant] ................................ 8 Aroha, avaroha [Ascending, Descending] ......................................................................................... 8 Twelve Swaras of the Octave ........................................................................................................... -

Trade Marks Journal No: 1869 , 01/10/2018 Class 32 1974588 03

Trade Marks Journal No: 1869 , 01/10/2018 Class 32 1974588 03/06/2010 JAYA WATEK INDUSTRIES trading as ;JAYA WATEK INDUSTRIES INDIRA GANDHI ROAD, MONGOLPUR, BALURGHAT,PIN 733103,W.B. MANUFACTURER & MERCHANT AN INDAIN COMPANY Used Since :02/04/2007 KOLKATA PACKGE DRINKING WATER, FRUIT DRINKS AND FRUIT JUICES, SOFT DRINKS, SYRUPSAND OTHER PREPARATIONS FOR MAKING BEVERAGES 5463 Trade Marks Journal No: 1869 , 01/10/2018 Class 32 BEY BLADER 2159631 14/06/2011 HECTOR BEVERAGES PVT. LTD B-82 SOUTH CITY -1 GURGAON 122001 SERVICE PROVIDER AN INCORPORATED COMPANY Address for service in India/Agents address: CHESTLAW H 2/4, MALVIYA NAGAR NEW DELHI-110017 Proposed to be Used DELHI BEVERAGES, NAMELY DRINKING WATERS, FLAVOURED WATERS, MINERAL AND AERATED WATERS AND OTHER NON-ALCOHOLIC BEVERAGES, NAMELY SOFT DRINKS, ENERGY DRINKS, AND SPORTS DRINKS, FRUIT DRINKS AND JUICES, SYRUPS, CONCENTRATES AND POWDERS FOR MAKING BEVERAGES, NAMELY FLAVORED WATERS, MINERAL AND AERATED WATERS, SOFT DRINKS, ENERGY DRINKS, SPORTS DRINKS, FRUIT DRINKS AND JUICES; DE- ALCOHOLISED DRINKS AND BEER ETC. 5464 Trade Marks Journal No: 1869 , 01/10/2018 Class 32 PowerPop 2299749 15/03/2012 ESSEN FOODDIES INDIA PVT,LTD. trading as ;ESSEN FOODDIES INDIA PVT,LTD. KINFRA (FOOD) SPECIAL ECONOMIC ZONE, KAKKANCHERY,CHELEMBRA P.O., MALAPPURAM - 673634 KERALA MANUFACTURERS AND MERCHANTS - Address for service in India/Attorney address: ANUP JOACHIM.T CC43/ 1983, SRSRA-2, SANTHIPURAM ROAD, COCHIN-682025,KERALA Proposed to be Used CHENNAI MINERAL AND AERATED WATER, NUTRITION DRINKS, ENERGY DRINKS, PACKAGED DRINKING WATER, FRUIT DRINKS AND FRUIT JUICES, SYRUPS, OTHER NON-ALCOHOLIC DRINKS. 5465 Trade Marks Journal No: 1869 , 01/10/2018 Class 32 2441929 13/12/2012 HIMANSHU BHATT DHIREN BHARAD trading as ;J. -

General Index

General Index Italic page numbers refer to illustrations. Authors are listed in ical Index. Manuscripts, maps, and charts are usually listed by this index only when their ideas or works are discussed; full title and author; occasionally they are listed under the city and listings of works as cited in this volume are in the Bibliograph- institution in which they are held. CAbbas I, Shah, 47, 63, 65, 67, 409 on South Asian world maps, 393 and Kacba, 191 "Jahangir Embracing Shah (Abbas" Abywn (Abiyun) al-Batriq (Apion the in Kitab-i balJriye, 232-33, 278-79 (painting), 408, 410, 515 Patriarch), 26 in Kitab ~urat ai-arc!, 169 cAbd ai-Karim al-Mi~ri, 54, 65 Accuracy in Nuzhat al-mushtaq, 169 cAbd al-Rabman Efendi, 68 of Arabic measurements of length of on Piri Re)is's world map, 270, 271 cAbd al-Rabman ibn Burhan al-Maw~ili, 54 degree, 181 in Ptolemy's Geography, 169 cAbdolazlz ibn CAbdolgani el-Erzincani, 225 of Bharat Kala Bhavan globe, 397 al-Qazwlni's world maps, 144 Abdur Rahim, map by, 411, 412, 413 of al-BlrunI's calculation of Ghazna's on South Asian world maps, 393, 394, 400 Abraham ben Meir ibn Ezra, 60 longitude, 188 in view of world landmass as bird, 90-91 Abu, Mount, Rajasthan of al-BlrunI's celestial mapping, 37 in Walters Deniz atlast, pl.23 on Jain triptych, 460 of globes in paintings, 409 n.36 Agapius (Mabbub) religious map of, 482-83 of al-Idrisi's sectional maps, 163 Kitab al- ~nwan, 17 Abo al-cAbbas Abmad ibn Abi cAbdallah of Islamic celestial globes, 46-47 Agnese, Battista, 279, 280, 282, 282-83 Mu\:lammad of Kitab-i ba/Jriye, 231, 233 Agnicayana, 308-9, 309 Kitab al-durar wa-al-yawaqft fi 11m of map of north-central India, 421, 422 Agra, 378 n.145, 403, 436, 448, 476-77 al-ra~d wa-al-mawaqft (Book of of maps in Gentil's atlas of Mughal Agrawala, V. -

Community Newsletter of by Giving Them Krsna ISKCON New York City, Sri Sri Radha Govinda Temple Consciousness

ISKCON New York City Sri Sri Radha Govinda Community Newsletter 0004 November 2019 International Society for Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON) Founder Acarya His Divine Grace A.C Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada Tapping into the store house of love of God Contents Diwali at Brooklyn Borough Hall...........................................2 Govardhan Puja...................................................................2 Srila Prabhupada's Disappearance Day................................3 Srila Prabhupada New York November 1965.......................3 Tulsi and Saligram wedding.................................................4 Thanksgiving dinner..............................................................4 HG Vaisesika gives his blessings.........................................5 Monthly Sankirtan Festival...................................................6 Halloween Harinam!............................................................8 Sri Vrindavana Dham...........................................................8 HG Malati devi dasi visits....................................................8 Sunday Japa Club................................................................9 What's cookin' ?....................................................................10 Spanish Bhagavad Gita Classes..........................................10 New Beginnings...................................................................11 Devotee of The Month...........................................................12 Alachua Holy Name Festival.................................................12 -

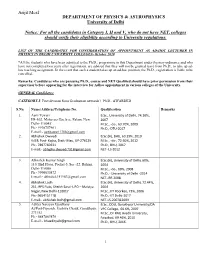

Arijit Mcaf DEPARTMENT of PHYSICS & ASTROPHYSICS

Arijit Mcaf DEPARTMENT OF PHYSICS & ASTROPHYSICS University of Delhi Notice: For all the candidates in Category I, II and V, who do not have NET, colleges should verify their eligibility according to University regulations. LIST OF THE CANDIDATES FOR CONSIDERATION OF APPOINTMENT AS AD-HOC LECTURER IN PHYSICS IN DELHI UNIVERSITY COLLEGES- October 2020 *All the students who have been admitted to the Ph.D., programme in this Department under the new ordinance and who have not completed two years after registration, are advised that they will not be granted leave from Ph.D., to take up ad- hoc teaching assignment. In the event that such a student takes up an ad-hoc position, the Ph.D., registration is liable to be cancelled. Remarks: Candidates who are pursuing Ph.D., course and NET Qualified should have prior permission from their supervisor before appearing for the interview for Adhoc appointment in various colleges of the University. GENERAL Candidates: CATEGORY-I: First division from Graduation onwards + Ph.D., AWARDED S.No. Name/Address/Telephone No. Qualification Remarks 1. Aarti Tewari B.Sc., University of Delhi, 74.10%, H4-102, Mahaveer Enclave, Palam, New 2007 Delhi-110045` M.Sc., -do-, 63.70%, 2009 Ph:- 9910757461 Ph.D.,-DTU-2017 E-mail:- [email protected] 2. Abhishek Dwivedi B.Sc.(H), BHU, 60.39%, 2010 Vill & Post- Kajha, Distt- Mau, UP-276129 M.Sc., -do-, 72.60%, 2012 Ph:- 7897760331 Ph.D., BHU, 2017 E-mail:- [email protected] NET- LS-2012 3. Abhishek Kumar Singh B.Sc.(H), University of Delhi, 60%, 110, IInd Floor, Pocket-5, Sec.-22, Rohini, 2004 Delhi-110086 M.Sc., -do-, 60%, 2008 Ph:- 9990030872 Ph.D.,- University of Delhi -2014 E-mail:- [email protected] NET-JRF-2008 4. -

Gates of the Lord: the Tradition of Krishna Paintings

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE JULY 29, 2015 MEDIA CONTACTS: Amanda Hicks Nina Litoff (312) 443-7297 (312) 443-3363 [email protected] [email protected] GATES OF THE LORD: THE TRADITION OF KRISHNA PAINTINGS AT THE ART INSTITUTE TO OFFER RARE GLIMPSE INTO ONE OF THE WORLD’S MOST INTIMATE AND PRIVATE RELIGIOUS TRADITIONS More than 100 Artworks from India and the United States Come Together in Chicago for a Groundbreaking Exhibition of Unique Indian Visual Culture CHICAGO—The Art Institute is proud to announce the opening of the highly anticipated special exhibition, Gates of the Lord: The Tradition of Krishna Paintings, on September 13, 2015 in Regenstein Hall where it will remain on view to audiences through January 3, 2016. Join the Art Institute of Chicago this fall to experience a stunning installation of more than 100 objects including pichvais—intricately painted cloth hangings—celebrating Shrinathji, a form of the Hindu god Krishna. This first of its kind large-scale exploration at any American museum of the art and aesthetics of the Pushtimarg sect of Hinduism, Gates of the Lord comprises a magnificent assembly of drawings, pichvais, paintings, and historic photographs. Madhuvanti Ghose, the Alsdorf Associate Curator of Indian, Southeast Asian, Himalayan and Islamic Art, highlights the special context for this exhibition saying, “This is a chance to showcase this very special artistic tradition to our audiences in the United States. Nathdwara and its artists are renowned for having preserved painting traditions in an unbroken legacy for more than four centuries. The exhibition provides us with an opportunity to celebrate these living traditional artists who have gone unrecognized for too long.” The extraordinary Lead Sponsorship of Nita and Mukesh Ambani and the Reliance Foundation and the generosity Anita and Prabhakant Sinha made it possible to borrow these artistic treasures from two prestigious and rarely exhibited private collections from India, the Amit Ambalal Collection (Ahmedabad, India) and the TAPI Collection (Surat, India). -

Catalogue Fair Timings

CATALOGUE Fair Timings 28 January 2016 Thursday Select Preview: 12 - 3pm By invitation Preview: 3 - 5pm By invitation Vernissage: 5 - 9pm IAF VIP Card holders (Last entry at 8.30pm) 29 - 30 January 2016 Friday and Saturday Business Hours: 11am - 2pm Public Hours: 2 - 8pm (Last entry at 7.30pm) 31 January 2016 Sunday Public Hours: 11am - 7pm (Last entry at 6.30pm) India Art Fair Team Director's Welcome Neha Kirpal Zain Masud Welcome to our 2016 edition of India Art Fair. Founding Director International Director Launched in 2008 and anticipating its most rigorous edition to date Amrita Kaur Srijon Bhattacharya with an exciting programme reflecting the diversity of the arts in Associate Fair Director Director - Marketing India and the region, India Art Fair has become South Asia's premier and Brand Development platform for showcasing modern and contemporary art. For our 2016 Noelle Kadar edition, we are delighted to present BMW as our presenting partner VIP Relations Director and JSW as our associate partner, along with continued patronage from our preview partner, Panerai. Saheba Sodhi Vishal Saluja Building on its success over the past seven years, India Art Senior Manager - Marketing General Manager - Finance Fair presents a refreshed, curatorial approach to its exhibitor and Alliances and Operations programming with new and returning international participants Isha Kataria Mankiran Kaur Dhillon alongside the best programmes from the subcontinent. Galleries, Vip Relations Manager Programming and Client Relations will feature leading Indian and international exhibitors presenting both modern and contemporary group shows emphasising diverse and quality content. Focus will present select galleries and Tanya Singhal Wol Balston organisations showing the works of solo artists or themed exhibitions. -

Gaudiya Math in Austria Keykey Elements of Cost for the Future, Based on the fi Nancial Support Received

Sriman Mahaprabhu and His Mission Who established the Sri Krishna Chaitanya Mission? audiya Vaishnavism is a spiritual move- e Modern Era he founder acharya of Sri After taking sannyas in 1940, He has started the Sri ment founded by Sri Krishna Chaitanya As time passed, the theology and practice of this Krishna Chaitanya Mission Krishna Chaitanya Mission in India. While preaching the Sri Sri Radha Govinda Gaudiya Math GMahaprabhu in India in the 15th century. pure devotional line were buried in ignorance and T is Om Vishnupada Srila message of Chaitanya Mahaprabhu he established 26 ‘Gaudiya’ refers to the Gaudiya region (present misconceptions. At this precarious time, in 1838 B.V. Puri Gosvami. He appeared in Gaudiya Maths in India, Italy, Spain, Mexico and Austria, day West Bengal/Bangladesh) with Vaishnavism Srila Bhaktivinoda akur was born in Birnagar in 1913 in a small village in Berham- additionally initiating thousands of disciples in the chant- NEW TEMPLE PROJECT meaning ‘ e worship of Vishnu (Krishna)’. Its the district of Nadia in West Bengal. After coming pur district, Orissa, India. After ing of the Holy Name. philosophical basis are Bhagavad Gita, Srimad in contact with the life and teachings of Sri Chait- completing his study of Ayurveda Bhagavatam as well as other puranic scriptures anya Mahaprabhu he focused all his activities on he opened a hospital and simul- Present Acharya in Austria and the Upanishads. Sri Krishna Chaitanya Ma- Sri Krishna Chaitanya the study and distribution of Mahaprabhu’s mes- taneously led Gandhi’s freedom Before he left this world he Mahaprabhu haprabhu (1486–1534) is the Yuga Avatar of Su- sage. -

A Reflection on the Challenges for Hindu Women in the Twenty-First

A Reflection on the Challenges for Hindu Women in the Twenty-first Century1 Neelima Shukla-Bhatt Introduction T the turn of the 21st century, it is clear that religion is not an insti- Atution of the past; it continues to be a powerful force in societies across the world. For this reason, some purely secularist and sociologi- cal theories of religion of the early twentieth century, which led to a wide spread view that religion was on the decline in the modern times, have proved to be limited, even though they are helpful in examining the social aspects of religious life.2 As Brian Hatcher suggests in a recent article, a major shortcoming of the secularist approaches to religion has been a purely dichotomous view of faith vs reason and tradition vs modernity. Instead of the demise of religion, Hatcher finds transforma- tion of religion with changing times, as proposed by sociologist Damiele Hervieu-Leger a more helpful way to understand religious phenomena (Hatcher 2006: 54–55). An aspect of religion that is widely debated with regard to need for transformation is treatment of women. In most organized religions of the world, women have not enjoyed equal rights with men. The norms assigned to them by male religious authorities have subjected them to various forms of marginalization. A major challenge for religious communities across the world today is to ensure that their religious practices and values are compatible with the ideal of gender equality as an aspect of the ideology of social justice, which is being widely upheld across the globe.