Yogi Heroes and Poets

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Abhinavagupta's Portrait of a Guru: Revelation and Religious Authority in Kashmir

Abhinavagupta's Portrait of a Guru: Revelation and Religious Authority in Kashmir The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:39987948 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Abhinavagupta’s Portrait of a Guru: Revelation and Religious Authority in Kashmir A dissertation presented by Benjamin Luke Williams to The Department of South Asian Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of South Asian Studies Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts August 2017 © 2017 Benjamin Luke Williams All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Parimal G. Patil Benjamin Luke Williams ABHINAVAGUPTA’S PORTRAIT OF GURU: REVELATION AND RELIGIOUS AUTHORITY IN KASHMIR ABSTRACT This dissertation aims to recover a model of religious authority that placed great importance upon individual gurus who were seen to be indispensable to the process of revelation. This person-centered style of religious authority is implicit in the teachings and identity of the scriptural sources of the Kulam!rga, a complex of traditions that developed out of more esoteric branches of tantric "aivism. For convenience sake, we name this model of religious authority a “Kaula idiom.” The Kaula idiom is contrasted with a highly influential notion of revelation as eternal and authorless, advanced by orthodox interpreters of the Veda, and other Indian traditions that invested the words of sages and seers with great authority. -

In the Name of Krishna: the Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town

In the Name of Krishna: The Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Sugata Ray IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Frederick M. Asher, Advisor April 2012 © Sugata Ray 2012 Acknowledgements They say writing a dissertation is a lonely and arduous task. But, I am fortunate to have found friends, colleagues, and mentors who have inspired me to make this laborious task far from arduous. It was Frederick M. Asher, my advisor, who inspired me to turn to places where art historians do not usually venture. The temple city of Khajuraho is not just the exquisite 11th-century temples at the site. Rather, the 11th-century temples are part of a larger visuality that extends to contemporary civic monuments in the city center, Rick suggested in the first class that I took with him. I learnt to move across time and space. To understand modern Vrindavan, one would have to look at its Mughal past; to understand temple architecture, one would have to look for rebellions in the colonial archive. Catherine B. Asher gave me the gift of the Mughal world – a world that I only barely knew before I met her. Today, I speak of the Islamicate world of colonial Vrindavan. Cathy walked me through Mughal mosques, tombs, and gardens on many cold wintry days in Minneapolis and on a hot summer day in Sasaram, Bihar. The Islamicate Krishna in my dissertation thus came into being. -

Srimad Bhagawadgita Which Is a Upanisad, Brahma Vidya and Yoga Sastras in the Form of a Dialogue Between Sri Krishna and Arjuna

Newsletter on Bhagavad Gita by Dr. P.V. Nath The following text is a compilation of the single issues of a regular newsletter by e-mail, composed by Dr. Pathikonda Viswambara Nath. It includes the original slokas of the Gita as well as the transliteration, translation and commentaries by Dr. Nath. Copyright to the commentaries on Bhagavad Gita: Dr. P.V. Nath, Great Britain. Inquiries concerning the text please direct to Dr. Nath at "[email protected]". Inquiries concerning the administration of the newsletter and the downloads please direct to [email protected]. To know more about Sri Swamiji, the Sadguru whose blessings made this newsletter possible, please visit: "www.dattapeetham.com" ___________________________________________________________________________ OM SAHA NAVAVATU SAHA NAU BHUNAKTU SAHA VEERYAM KARAVAVAHAI TEJASWI NAVADHEETAMASTU MAA VID VISHAVAHAI May He protect us both (the teacher and the pupil) May He cause us both to enjoy (the Supreme) May we both exert together (to discover the true inner meaning of the scriptures) May our studies be thorough and fruitful. May we never misunderstand each other. ___________________________________________________________________________ The Gita is in the form of dialogue between Krishna, the preceptor and the disciple Arjuna. Sanjaya, the narrator to King Dhritarashtra, intercepts now and then with a comment of his own. There are a total of 18 chapters with 701 verses (slokas.) Each of the chapters has a title and the title ends with the word “Yoga”. The word “Yoga” is derived from the word “Yuj” which means “Unite.” Study of every chapter assists the seeker to unite with the Lord and hence the use of the word “Yoga.” The seeker is he/she who is looking for attaining the union with the “Parabrahman” and experience the “Eternal Bliss.” In Sanskrit the name for the word “seeker” is “Sadhaka”. -

A Translation of the Vijñāna-Bhairava-Tantra (Complete but Lacking Commentary) ©2017 by Christopher Wallis Aka Hareesh

A translation of the Vijñāna-bhairava-tantra (complete but lacking commentary) ©2017 by Christopher Wallis aka Hareesh Introductory verse (maṅgala-śloka): “Shiva is also known as ‘Bhairava’ because He brings about the [initial awakening that makes us] cry out in fear of remaining in the dreamstate (bhava-bhaya)—and due to that cry of longing he becomes manifest in the radiant domain of the heart, bestowing absence of fear (abhaya) for those who are terrified. He is also known as Bhairava because he is the Lord of those who delight in his awesome roar (bhīrava), which signals the death of Death! Being the Master of that flock of excellent Yogins who tire of fear and seek release, he is Bhairava—the Supreme, whose form is Consciousness (vijñāna). As the giver of nourishment, he extends his Power throughout the universe!” ~ the great master Rājānaka Kṣemarāja, c. 1020 CE Like most Tantrik scriptures, the Vijñāna-bhairava-tantra (c. 850 CE) takes the form of a dialogue between Śiva and Śakti, here called Bhairava and Bhairavī. It begins with the Goddess asking Bhairava: śrutaṃ deva mayā sarvaṃ rudra-yāmala-saṃbhavam | trika-bhedam aśeṣeṇa sārāt sāra-vibhāgaśaḥ || 1 || . 1. O Lord, I have heard the entire teaching of the Trika1 that has arisen from our union, in scriptures of ever greater essentiality, 2. but my doubts have not yet dissolved. What is the true nature of Reality, O Lord? Does it consist of the powers of the mystic alphabet (śabda-rāśi)?2 3. Or, amongst the terrifying forms of Bhairava, is it Navātman?3 Or is it the trinity of śaktis (Parā, Parāparā, and Aparā) that [also] constitute the three ‘heads’ of Triśirobhairava? 4. -

The Decline of Buddhism in India

The Decline of Buddhism in India It is almost impossible to provide a continuous account of the near disappearance of Buddhism from the plains of India. This is primarily so because of the dearth of archaeological material and the stunning silence of the indigenous literature on this subject. Interestingly, the subject itself has remained one of the most neglected topics in the history of India. In this book apart from the history of the decline of Buddhism in India, various issues relating to this decline have been critically examined. Following this methodology, an attempt has been made at a region-wise survey of the decline in Sind, Kashmir, northwestern India, central India, the Deccan, western India, Bengal, Orissa, and Assam, followed by a detailed analysis of the different hypotheses that propose to explain this decline. This is followed by author’s proposed model of decline of Buddhism in India. K.T.S. Sarao is currently Professor and Head of the Department of Buddhist Studies at the University of Delhi. He holds doctoral degrees from the universities of Delhi and Cambridge and an honorary doctorate from the P.S.R. Buddhist University, Phnom Penh. The Decline of Buddhism in India A Fresh Perspective K.T.S. Sarao Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd. ISBN 978-81-215-1241-1 First published 2012 © 2012, Sarao, K.T.S. All rights reserved including those of translation into other languages. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher. -

Essays and Addresses on the Śākta Tantra-Śāstra

ŚAKTI AND ŚĀKTA ESSAYS AND ADDRESSES ON THE ŚĀKTA TANTRAŚĀSTRA BY SIR JOHN WOODROFFE THIRD EDITION REVISED AND ENLARGED Celephaïs Press Ulthar - Sarkomand - Inquanok – Leeds 2009 First published London: Luzac & co., 1918. Second edition, revised and englarged, London: Luzac and Madras: Ganesh & co., 1919. Third edition, further revised and enlarged, Ganesh / Luzac, 1929; many reprints. This electronic edition issued by Celephaïs Press, somewhere beyond the Tanarian Hills, and mani(n)fested in the waking world in Leeds, England in the year 2009 of the common error. This work is in the public domain. Release 0.95—06.02.2009 May need furthur proof reading. Please report errors to [email protected] citing release number or revision date. PREFACE TO THIRD EDITION. HIS edition has been revised and corrected throughout, T and additions have been made to some of the original Chapters. Appendix I of the last edition has been made a new Chapter (VII) in the book, and the former Appendix II has now been attached to Chapter IV. The book has moreover been very considerably enlarged by the addition of eleven new Chapters. New also are the Appendices. The first contains two lectures given by me in French, in 1917, before the Societé Artistique et Literaire Francaise de Calcutta, of which Society Lady Woodroffe was one of the Founders and President. The second represents the sub- stance (published in the French Journal “Le Lotus bleu”) of two lectures I gave in Paris, in the year 1921, before the French Theosophical Society (October 5) and at the Musée Guimet (October 6) at the instance of L’Association Fran- caise des amis de L’Orient. -

Aesthetic Philosophy of Abhina V Agupt A

AESTHETIC PHILOSOPHY OF ABHINA V AGUPT A Dr. Kailash Pati Mishra Department o f Philosophy & Religion Bañaras Hindu University Varanasi-5 2006 Kala Prakashan Varanasi All Rights Reserved By the Author First Edition 2006 ISBN: 81-87566-91-1 Price : Rs. 400.00 Published by Kala Prakashan B. 33/33-A, New Saket Colony, B.H.U., Varanasi-221005 Composing by M/s. Sarita Computers, D. 56/48-A, Aurangabad, Varanasi. To my teacher Prof. Kamalakar Mishra Preface It can not be said categorically that Abhinavagupta propounded his aesthetic theories to support or to prove his Tantric philosophy but it can be said definitely that he expounded his aesthetic philoso phy in light of his Tantric philosophy. Tantrism is non-dualistic as it holds the existence of one Reality, the Consciousness. This one Reality, the consciousness, is manifesting itself in the various forms of knower and known. According to Tantrism the whole world of manifestation is manifesting out of itself (consciousness) and is mainfesting in itself. The whole process of creation and dissolution occurs within the nature of consciousness. In the same way he has propounded Rasadvaita Darsana, the Non-dualistic Philosophy of Aesthetics. The Rasa, the aesthetic experience, lies in the conscious ness, is experienced by the consciousness and in a way it itself is experiencing state of consciousness: As in Tantric metaphysics, one Tattva, Siva, manifests itself in the forms of other tattvas, so the one Rasa, the Santa rasa, assumes the forms of other rasas and finally dissolves in itself. Tantrism is Absolute idealism in its world-view and epistemology. -

Troubling Questions and Beyond-Naive Answers

Troubling Questions and Beyond-naive answers H. S. Mukunda, IISc, Bangalore, July 2012 1. Troubling questions? 2. The beginning of “God” in one’s life; defining God? 3. Being contented is good? Being ambitious in life bad? 4. Is science below spirituality? Is spirituality beyond science? 5. Is the state of Sanyāsa great? Is the state of Avadhūta better? 6. Freedom and anonymity 7. Conscious and unconscious parts of the mind 8. 20 minute meditation and other life afterwards? 9. How long to meditate? 10. Can practice of Music lead to Nirvana? 11. Vedic chāntings, alternate to music? Japā an alternate route? 12. Yagnas and burning firewood – clean combustion? 13. Living on beliefs – for how long? 14. Fate or freewill? 15. Great books needed? Watchful passage not adequate? 16. Great men – who and why? 17. Bibiography Preface Traditional upbringing that I came through has had its positive points – devotion to scholastics and being respectful of the scriptures that led me to trust broad understanding that filtered into me from various sources till I was 21. Upsetting of several thoughts took place with Sri. Poornananda tirtha swami who gave lectures on Vedānta, Bhagavadgita and Yoga Vāsishța over several years at Bangalore between 1965 – 1969. His more-than incisive statements led to intensive discussion amongst colleagues and self-examination of the truth of scriptural writings. Professional demands over the next thirty-four years led to setting aside the intensity of pursuit to seek answers to the questions. Tradition held its sway over the mind – issues of miracles, their authenticity, and their importance to life were not dismissed easily. -

Brill's Encyclopedia of Hinduism

Brill’s Encyclopedia of Hinduism HANDBOOK OF ORIENTAL STUDIES HANDBUCH DER ORIENTALISTIK SECTION TWO INDIA edited by J. Bronkhorst A. Malinar VOLUME 22/5 Brill’s Encyclopedia of Hinduism Volume V: Religious Symbols Hinduism and Migration: Contemporary Communities outside South Asia Some Modern Religious Groups and Teachers Edited by Knut A. Jacobsen (Editor-in-Chief ) Associate Editors Helene Basu Angelika Malinar Vasudha Narayanan Leiden • boston 2013 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Brill’s encyclopedia of Hinduism / edited by Knut A. Jacobsen (editor-in-chief); associate editors, Helene Basu, Angelika Malinar, Vasudha Narayanan. p. cm. — (Handbook of oriental studies. Section three, India, ISSN 0169-9377; v. 22/5) ISBN 978-90-04-17896-0 (hardback : alk. paper) 1. Hinduism—Encyclopedias. I. Jacobsen, Knut A., 1956- II. Basu, Helene. III. Malinar, Angelika. IV. Narayanan, Vasudha. BL1105.B75 2009 294.503—dc22 2009023320 ISSN 0169-9377 ISBN 978 90 04 17896 0 Copyright 2013 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Global Oriental, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers and Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Brill provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. Fees are subject to change. Printed in the Netherlands Table of Contents, Volume V Prelims Preface .............................................................................................................................................. -

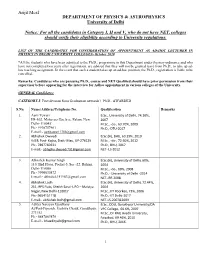

Arijit Mcaf DEPARTMENT of PHYSICS & ASTROPHYSICS

Arijit Mcaf DEPARTMENT OF PHYSICS & ASTROPHYSICS University of Delhi Notice: For all the candidates in Category I, II and V, who do not have NET, colleges should verify their eligibility according to University regulations. LIST OF THE CANDIDATES FOR CONSIDERATION OF APPOINTMENT AS AD-HOC LECTURER IN PHYSICS IN DELHI UNIVERSITY COLLEGES- October 2020 *All the students who have been admitted to the Ph.D., programme in this Department under the new ordinance and who have not completed two years after registration, are advised that they will not be granted leave from Ph.D., to take up ad- hoc teaching assignment. In the event that such a student takes up an ad-hoc position, the Ph.D., registration is liable to be cancelled. Remarks: Candidates who are pursuing Ph.D., course and NET Qualified should have prior permission from their supervisor before appearing for the interview for Adhoc appointment in various colleges of the University. GENERAL Candidates: CATEGORY-I: First division from Graduation onwards + Ph.D., AWARDED S.No. Name/Address/Telephone No. Qualification Remarks 1. Aarti Tewari B.Sc., University of Delhi, 74.10%, H4-102, Mahaveer Enclave, Palam, New 2007 Delhi-110045` M.Sc., -do-, 63.70%, 2009 Ph:- 9910757461 Ph.D.,-DTU-2017 E-mail:- [email protected] 2. Abhishek Dwivedi B.Sc.(H), BHU, 60.39%, 2010 Vill & Post- Kajha, Distt- Mau, UP-276129 M.Sc., -do-, 72.60%, 2012 Ph:- 7897760331 Ph.D., BHU, 2017 E-mail:- [email protected] NET- LS-2012 3. Abhishek Kumar Singh B.Sc.(H), University of Delhi, 60%, 110, IInd Floor, Pocket-5, Sec.-22, Rohini, 2004 Delhi-110086 M.Sc., -do-, 60%, 2008 Ph:- 9990030872 Ph.D.,- University of Delhi -2014 E-mail:- [email protected] NET-JRF-2008 4. -

Date:/9/04/031 ORDER 1 .Vide Order No.05/G-Gaz.-IA/DHC/2021 Dated 29.01.2021, the Hon'ble High Court of Delhi Has Created Three New Labour Courts

GOVERNMENT OF NATIONAL CAPITAL TERRITORY OF DELHI LABOUT DEPARTMENT 5-SHAM NATH MARG, DELHI-110054 F.No.15(16)/Lab/2021//695- 1706 Date:/9/04/031 ORDER 1 .Vide order no.05/G-Gaz.-IA/DHC/2021 Dated 29.01.2021, the Hon'ble High Court of Delhi has created three new Labour Courts. The Labour Courts have been designated as under: S.No Labour COurt no. Ld. Presiding Officer Labour Court-01 2 Smt. Veena Rani Labour Court-02 Sh. Pawan Kumar Matto_ Labour Court-03 Sh. Raj kumar Labour Court-04 Sh Gorakh Nath Pandey Labour Court-05_ Sh. Sanatan Prasad Labour Court-06 Sh. Ramesh Kumar-II 7 Labour Court-07 Ms. Navita kumari Bagha 8 Labour Court-08 Sh. Tarun Yogesh 9 Labour Court-09 Sh. Joginder Prakash Nahar 2. Vide this office order no. F.No. 15(16)Lab/2021/647 dated 08.02.2021, the newly constituted Labour Courts have been transferred cases. All the district Joint Labour Commissioner/Deputy Labour Commissioner shall make reference of new Industrial Disputes to Labour Courts as per Table mentioned below District Area falling under following Police Stations Labour Court South Saket, Neb sarai , Hauz Khas . Malviya Nagar, Mehrauli , Fatehpur Beri, Labour Court No.l Lajpat Nagar, Amar colony. Defence Colony. Lodhi Colony, Hazrat Nizamuddin, Sriniwas Puri, Greater Kailash, Chitranjan Park, Kalkaji, Badarpur, Okhla Indl. Area, Ambedkar Nagar, Kotla Jamia Mubarakpur, Nagar, Sunlight Colony , Sangam vihar, Govind puri , Pul Prahlad puri, , Sarita vihar , Newfriends Colony, Jaitpur Labour Court No.2 South- Vasant Vihar, Vasant Kunj, Mahipalpur, RK. -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita