Ghengis Khan, History's Greatest Empire Builder

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nomadic Incursion MMW 13, Lecture 3

MMW 13, Lecture 3 Nomadic Incursion HOW and Why? The largest Empire before the British Empire What we talked about in last lecture 1) No pure originals 2) History is interrelated 3) Before Westernization (16th century) was southernization 4) Global integration happened because of human interaction: commerce, religion and war. Known by many names “Ruthless” “Bloodthirsty” “madman” “brilliant politician” “destroyer of civilizations” “The great conqueror” “Genghis Khan” Ruling through the saddle Helped the Eurasian Integration Euroasia in Fragments Afro-Eurasia Afro-Eurasian complex as interrelational societies Cultures circulated and accumulated in complex ways, but always interconnected. Contact Zones 1. Eurasia: (Hemispheric integration) a) Mediterranean-Mesopotamia b) Subcontinent 2) Euro-Africa a) Africa-Mesopotamia 3) By the late 15th century Transatlantic (Globalization) Africa-Americas 12th century Song and Jin dynasties Abbasids: fragmented: Fatimads in Egypt are overtaken by the Ayyubid dynasty (Saladin) Africa: North Africa and Sub-Saharan Africa Europe: in the periphery; Roman catholic is highly bureaucratic and society feudal How did these zones become connected? Nomadic incursions Xiongunu Huns (Romans) White Huns (Gupta state in India) Avars Slavs Bulgars Alans Uighur Turks ------------------------------------------------------- In Antiquity, nomads were known for: 1. War 2. Migration Who are the Nomads? Tribal clan-based people--at times formed into confederate forces-- organized based on pastoral or agricultural economies. 1) Migrate so to adapt to the ecological and changing climate conditions. 2) Highly competitive on a tribal basis. 3) Religion: Shamanistic & spirit-possession Two Types of Nomadic peoples 1. Pastoral: lifestyle revolves around living off the meat, milk and hides of animals that are domesticated as they travel through arid lands. -

The Great Empires of Asia the Great Empires of Asia

The Great Empires of Asia The Great Empires of Asia EDITED BY JIM MASSELOS FOREWORD BY JONATHAN FENBY WITH 27 ILLUSTRATIONS Note on spellings and transliterations There is no single agreed system for transliterating into the Western CONTENTS alphabet names, titles and terms from the different cultures and languages represented in this book. Each culture has separate traditions FOREWORD 8 for the most ‘correct’ way in which words should be transliterated from The Legacy of Empire Arabic and other scripts. However, to avoid any potential confusion JONATHAN FENBY to the non-specialist reader, in this volume we have adopted a single system of spellings and have generally used the versions of names and titles that will be most familiar to Western readers. INTRODUCTION 14 The Distinctiveness of Asian Empires JIM MASSELOS Elements of Empire Emperors and Empires Maintaining Empire Advancing Empire CHAPTER ONE 27 Central Asia: The Mongols 1206–1405 On the cover: Map of Unidentified Islands off the Southern Anatolian Coast, by Ottoman admiral and geographer Piri Reis (1465–1555). TIMOTHY MAY Photo: The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore. The Rise of Chinggis Khan The Empire after Chinggis Khan First published in the United Kingdom in 2010 by Thames & Hudson Ltd, 181A High Holborn, London WC1V 7QX The Army of the Empire Civil Government This compact paperback edition first published in 2018 The Rule of Law The Great Empires of Asia © 2010 and 2018 Decline and Dissolution Thames & Hudson Ltd, London The Greatness of the Mongol Empire Foreword © 2018 Jonathan Fenby All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced CHAPTER TWO 53 or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, China: The Ming 1368–1644 including photocopy, recording or any other information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. -

LIBRO El Imperio Mongol.Indb

EL IMPERIO MONGOL Temas de Historia Medieval Coordinador: JOSÉ MARÍA MONSALVO ANTÓN EL IMPERIO MONGOL Antonio García Espada Consulte nuestra página web: www.sintesis.com En ella encontrará el catálogo completo y comentado © Antonio García Espada © EDITORIAL SÍNTESIS, S. A. Vallehermoso, 34. 28015 Madrid Teléfono: 91 593 20 98 www.sintesis.com ISBN: 978-84-9171-051-6 Depósito Legal: M-29.570-2017 Impreso en España - Printed in Spain Reservados todos los derechos. Está prohibido, bajo las sanciones penales y el resarcimiento civil previstos en las leyes, reproducir, registrar o transmitir esta publicación, íntegra o parcialmente, por cualquier sistema de recuperación y por cualquier medio, sea mecánico, electrónico, magnético, electroóptico, por fotocopia o por cualquier otro, sin la autorización previa por escrito de Editorial Síntesis, S. A. ÍNDICE INTRODUCCIÓN . 11 PARTE I CHINGGIS KHAN (1162-1227) 1. LA HISTORIA SECRETA DE LOS MONGOLES . 23 1 .1 . Temuyin . 24 1 .1 .1 . Yesugei . 25 1 .1 .2 . Hoelun . 26 1 .1 .3 . La estepa . 27 1 .1 .4 . El despertar de Temuyin . 30 1 .1 .5 . El rapto de Borte . 32 1 .1 .6 . La guerra contra Jamuqa . 33 1 .1 .7 . La victoria sobre los keraítas . 35 1 .1 .8 . La victoria sobre los naimanos . 36 1 .2 . LaHistoria secreta . 38 1 .2 .1 . La datación de la Historia secreta . 39 1 .2 .2 . Fuentes alternativas . 40 1 .2 .3 . Composición literaria . 41 1 .2 .4 . Cosmovisión de la Historia secreta . 42 2. EL IMPERIO DE CHINGGIS KHAN . 45 2 .1 . La conquista del mundo sedentario . 45 2 .1 .1 . -

Chinggis Khan and His Conquest of Khorasan: Causes and Consequences

CHINGGIS KHAN AND HIS CONQUEST OF KHORASAN: CAUSES AND CONSEQUENCES BY ANIBA ISRAT ARA ARSHAD ISLAM INTERNATIONAL ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY MALAYSIA ABSTRACT This book explores the causes and consequences of Chinggis Khan’s invasion of Khorasan in the 13th century. It discusses Chinggis Khan’s charismatic leadership qualities that united all nomadic tribes and gave him the authority to become the supreme Mongol leader, which helped him to invade Khorasan. It also focuses on the rise of the Muslim cities in Khorasan where many Muslim scholars kept their intellectual brilliance and made Khorasan the cultural capital of the Muslims. This study apprises us of Chinggis Khan’s war tactics and administrative system which made his men extremely strong and advanced despite their culture remaining barbaric in nature. His progeny also followed a similar policy for a long time until all Muslim cities were fully destroyed. The work also focuses on the rise of many sectarian divisions among the Muslims which brought disunity that eventually led to their downfall. Thus, this study underscores the importance of revitalization of unity in the Muslim world so that Muslims may not become vulnerable to any foreign imperialistic power. Unity also is the key to preserve Muslim intellectual thought and Islamic cultural identities. i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS In the beginning, I would like to say that all praise is to Allah (swt) Almighty; despite the difficulties, with His mercy, and the strength, patience and resilience that He has bestowed on me, I completed my work. I am heartily thankful to my beloved supervisor to Dr. Arshad Islam, whose encouragement, painstaking supervision and tireless motivating from the beginning of my long journey to the concluding level helped me to complete this study. -

The Fate of Medical Knowledge and the Neurosciences During the Time of Genghis Khan and the Mongolian Empire

Neurosurg Focus 23 (1):E13, 2007 The fate of medical knowledge and the neurosciences during the time of Genghis Khan and the Mongolian Empire SAM SAFAVI-ABBASI, M.D., PH.D.,1 LEONARDO B. C. BRASILIENSE, M.D.,2 RYAN K. WORKMAN, B.S.,2 MELANIE C. TALLEY, PH.D.,2 IMAN FEIZ-ERFAN, M.D.,1 NICHOLAS THEODORE, M.D.,1 ROBERT F. SPETZLER, M.D.,1 AND MARK C. PREUL, M.D.1 1Division of Neurological Surgery, Neurosurgery Research; and 2Spinal Biomechanics Laboratory, Barrow Neurological Institute, St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center, Phoenix, Arizona PIn 25 years, the Mongolian army of Genghis Khan conquered more of the known world than the Roman Empire accomplished in 400 years of conquest. The recent revised view is that Genghis Khan and his descendants brought about “pax Mongolica” by securing trade routes across Eurasia. After the initial shock of destruction by an unknown barbaric tribe, almost every country conquered by the Mongols was transformed by a rise in cultural communication, expanded trade, and advances in civiliza- tion. Medicine, including techniques related to surgery and neurological surgery, became one of the many areas of life and culture that the Mongolian Empire influenced. (DOI: 10.3171/FOC-07/07/E13) KEY WORDS • Avicenna • Genghis Khan • history of neuroscience • Mongolian empire • Persia EPORTS ABOUT THE HISTORY of medicine in Asia are golica” and secured the fabled trade routes between scarce. This article provides an overview of the fate Europe and eastern China known as the Silk Road.8,23 R of Asian medicine, specifically Persian, Indian, and After the initial shock and destruction associated with Chinese scientific, neurological, and surgical knowledge invasion by an unknown barbaric tribe, almost every before and during the Mongolian invasion and hegemony. -

Jack Gavigan the Memories of Chingiz Khan

Jack Gavigan The Memories of Chingiz Khan Around 1226- Heisui Chingiz and a few men swept out of camp. It was late afternoon and he knew that his arban, composed of ten of his most faithful warriors, would probably be unneeded. It was still better to be cautious and bring them. The landscape around the camp called to him. Chingiz was older than sixty, but he still had the same urge to explore as when he was a child. Some areas on the journey to Heisui, in Western Xia, reminded him of his home in Delun-Boldaq. Ever since he saw those steep rock slopes a few days ago, he had been experiencing an irresistible urge to climb. He wasn’t sure what it was about scaling rock faces. Maybe the required combination of agility and strength, the ability to see your enemy, or that feeling of welcome given off when one gets closer to the Blue Mighty Eternal Heaven. Whatever it was, it had always captivated him. Chingiz steered his horse to one large slab of rock that struck his eye. It was about two hundred and fifty ald to the top, and there was a section of steep overhang in the middle of the climb. Chingiz looked at his men and called, “Anyone want to get closer to the Blue Sky? Now’s your chance.” They seemed paralyzed. All of them wanted to show the khan their strength, but they also didn’t want to embarrass themselves, and many felt uncomfortable with heights. After all, they were a people of the steppe, not of the mountain. -

'Genghis Khan: History's Greatest Empire Builder'

H-War May on Lococo, 'Genghis Khan: History's Greatest Empire Builder' Review published on Saturday, November 22, 2008 Paul Lococo. Genghis Khan: History's Greatest Empire Builder. Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, 2008. ix + 91 pp. + 4 pp. of plates. $21.95 (cloth), ISBN 978-1-57488-571-2; $13.95 (paper), ISBN 978-1-57488-746-4. Reviewed by Timothy May Published on H-War (November, 2008) Commissioned by Brian G.H. Ditcham Ghengis Khan, History's Greatest Empire builder Genghis Khan, or more accurately Chinggis Khan, is undoubtedly one of the most fascinating people in military history. Thus it is not surprising that Potomac Books has included him in their Military Profile series along with General Patton and Alexander the Great. As with all of the books in the series, the volume is not an in-depth study presenting new revelations, but rather a concise introduction to a key figure in military history accompanied by some analysis of the topic's activities. Paul Lococo Jr. adeptly summarizes the life and career of Chinggis Khan, an impressive feat for the brevity of the book. The book is divided in to seven chapters. The first is a standard chapter on the geographical, political, and social state of Mongolia in the medieval period. This is followed by a chapter on the early years of Chinggis Khan and a chapter on the wars that unified Mongolia under Chinggis Khan. Chapter 4 provides a lucid discussion of the military revolution of Chinggis Khan. Chapters 5 through 7 focus on Chinggis Khan's military conquests outside of Mongolia. -

Chapter 1 - Genghis Khan's Overwhelming Standing Started with Humble Inceptions in the Troublesome Territory

In the West, we frequently consider the Greek and Roman Empires the incredible cultivating impacts that prompted the improvement of the advanced world as we probably are aware of it. The Mongol Empire and Genghis Khan, then again, get an insufficient notification from Western students of history. On the events they are referenced, it's quite often in a negative setting, with stories of ruthlessness and hostility. Be that as it may, the account of Genghis Khan and his empire is captivating and merits returning to. It is a story that necessities telling. From the difficulties of Genghis Khan's adolescence to the development of the principal business empire to intently associate the European and Asian landmasses, this synopsis recount the ruler's genuine story. Chapter 1 - Genghis Khan's overwhelming standing started with humble inceptions in the troublesome territory. You might've thought the future empire developer Genghis Khan had a favored existence from youth. That he came from a ground-breaking and affluent family and stayed amazing and rich. He didn't. Genghis Khan confronted numerous difficulties as a kid. Brought into the world in the Eurasian Steppe between cutting edge Mongolia and Siberia, he was given the name Temujin and experienced childhood in a migrant culture. The migrant people groups of the zone blended into clans and families dependent on connection ties. The top of every tribe was known as a khan or boss. However, it was a hazardous world. The tradition that must be adhered to was viciousness. Murder, capturing, and subjugation between families were typical. -

Studies in the Career of Chinggis Qan

1 Studies in the Career of Chinggis Qan Chih-Shu Eva CHENG Doctor of Philosophy (1996) School of Oriental and African Studies University of London ProQuest Number: 10731733 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10731733 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 2 ABSTRACT At the turn of twelfth and thirteenth centuries, a Mongol chief, Temujin, best-known by his title Chinggis Qan, began his expansion and created a vast empire in north and central Asia. The conquest was completed in three stages: first the unification of Mongolia, second the submission of neighbouring nations, third an expedition to Central Asia. The history of his military conquests has been extensively studied by modem researchers, while the non-military factors which also contribute to his success have been given less attention. The background of Temujin’s success lacks clarity too, because of confusion in the available accounts. This thesis focus on two topics in the career of Temujin. The first three chapters in part one analyze the relationship between Temujin’s family and Toyoril, the ruler of the Turkic Kereit tribe, who was a crucial figure in Temujin’s rise to power. -

The Reception and Management of Gifts in the Imperial Court of the Mongol Great Khan, from the Early Thirteenth Century to 1368

Ya Ning The Reception and Management of Gifts in the Imperial Court of the Mongol Great Khan, from the early thirteenth century to 1368 MA Thesis in Late Antique, Medieval and Early Modern Studies Central European University Budapest May 2020 CEU eTD Collection The Reception and Management of Gifts in the Imperial Court of the Mongol Great Khan, from the early thirteenth century to 1368 by Ya Ning (China) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Late Antique, Medieval and Early Modern Studies. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. ____________________________________________ Chair, Examination Committee ____________________________________________ Thesis Supervisor ____________________________________________ Examiner ____________________________________________ Examiner Budapest CEU eTD Collection May 2020 The Reception and Management of Gifts in the Imperial Court of the Mongol Great Khan, from the early thirteenth century to 1368 by Ya Ning (China) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Late Antique, Medieval and Early Modern Studies. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. ____________________________________________ External Reader Budapest CEU eTD Collection May 2020 The Reception and Management of Gifts in the Imperial Court of the Mongol Great Khan, from the early thirteenth century to 1368 by Ya Ning (China) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Late Antique, Medieval and Early Modern Studies. -

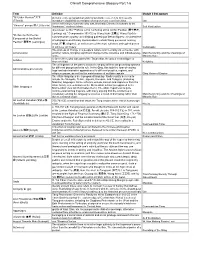

Chinax Comprehensive Glossary Part 1-6

ChinaX Comprehensive Glossary Part 1-6 Term Definition Module it first appears "All Under Heaven" 天下 denotes entire geographical and mortal world. Here, refers to heavenly (Tiānxià) investiture of political sovereignty of emperor over a unified China Qin a term referring to someone who was ethnically Chinese in contrast to the "Chinese" person 漢人 (Hàn rén) "barbarian," northern tribes Self Realization also known as the "Preface to the Gathering at the Orchid Pavilion (蘭亭集序, Lántíngjí xù)." Composed in 353 CE by Wang Xizhi (王羲之 Wáng Xīzhī) to "Preface to the Poems commemorate a poetry and drinking gathering of literary figures; a masterpiece Composed at the Orchid of calligraphic and literary improvisation in which Wang pioneered running Pavilion" 蘭亭序 (Lántíngxù) script (行書, xíngshū), as well as one of the most collected and copied pieces in Chinese art history Calligraphy The process of change in a people's culture and mentality via encounter with Acculturation another culture, bringing significant change to the collective and individual way Manchu Identity and the Meanings of of life. Minority Rule A Greek Hero who was part of the Trojan War. He was a central figure in Achilles Homer's Illiad. Keightley The willingness on the part of a state to employ differential governing systems for different groups under its rule. In the Qing, this took the form of varying Administrative promiscuity legal and administrative apparatuses for different peoples, regions, and religious groups, as well as the maintenance of multiple capitals. Qing Vision of Empire The Altaic languages are a proposed language family usually believed to include the Mongolic, Turkic, Japonic, Koreanic, and Tungusic (including Manchu) languages. -

The World Empire of the Mongols

Week 20 The World Empire of the Mongols Historical Overview The Song, as we've seen, emerged in a multi-state world. Its power no longer reached Central Asia, as had that of the Tang, and closer to home, powerful regimes had entrenched themselves firmly within the former northern territories of the Tang. These regimes, those of the Khitan people in the Northeast, with the Liao Dynasty, and the Tangut people in the Northwest, who would eventually form the Western Xia, had established sophisticated systems of multiethnic administration and power projection. But while this northern influence on China would persist and expand in the period that we are about to study, the actors would change. Early in the 12th century, the Jurchens, a nomadic people of the far Northeast, established the Jin dynasty and proceeded to conquer the Liao to their west, and then in 1126, to attack the Song, taking the Song capital of Kaifeng and most of northern China. The result is a division in Song history between the Northern Song and the Southern Song. The Song reconstitutes itself at Hangzhou, and by 1142, signs a peace treaty with the Jin. But even greater change was still to come from this northern border. Out of a resource crisis in the northern steppe at the end of the 12th century and in a world of continental trade and changing central Asian empires, Ghengis Khan unified the tribes of the steppe under a single ruler, and with them created an army that would cross into central Asia and then turn back and conquer Western Xia and Jin.