Water-Art Problems at Sanssouci

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Things to Do in Berlin – a List of Options 19Th of June (Wednesday

Things to do in Berlin – A List of Options Dear all, in preparation for the International Staff Week, we have composed an extensive list of activities or excursions you could participate in during your stay in Berlin. We hope we have managed to include something for the likes of everyone, however if you are not particularly interested in any of the things listed there are tons of other options out there. We recommend having a look at the following websites for further suggestions: https://www.berlin.de/en/ https://www.top10berlin.de/en We hope you will have a wonderful stay in Berlin. Kind regards, ??? 19th of June (Wednesday) / Things you can always do: - Famous sights: Brandenburger Tor, Fernsehturm (Alexanderplatz), Schloss Charlottenburg, Reichstag, Potsdamer Platz, Schloss Sanssouci in Potsdam, East Side Gallery, Holocaust Memorial, Pfaueninsel, Topographie des Terrors - Free Berlin Tours: https://www.neweuropetours.eu/sandemans- tours/berlin/free-tour-of-berlin/ - City Tours via bus: https://city- sightseeing.com/en/3/berlin/45/hop-on-hop-off- berlin?utm_source=google&utm_medium=cpc&gclid=EAIaIQobChMI_s2es 9Pe4AIVgc13Ch1BxwBCEAAYASAAEgInWvD_BwE - City Tours via bike: https://www.fahrradtouren-berlin.com/en/ - Espresso-Concerts: https://www.konzerthaus.de/en/espresso- concerts - Selection of famous Museums (Museumspass Berlin buys admission to the permanent exhibits of about 50 museums for three consecutive days. It costs €24 (concession €12) and is sold at tourist offices and participating museums.): Pergamonmuseum, Neues Museum, -

Sanssouci Park H 3 Picture Gallery of Sanssouci

H 1 SANSSOUCI PALACE 12 TEMPLE OF FRIENDSHIP Pappelallee NOT ACCESSIBLE 2 NORMAN TOWER 13 NEW PALACE SANSSOUCI PARK H 3 PICTURE GALLERY OF SANSSOUCI 14 COLONNADE WITH THE TRIUMPHAL ARCH, Ruinenberg 4 NEPTUNE GROTTO NEW PALACE Amundsenstr. Schlossgarten Lindstedt NOT ACCESSIBLE 15 TEMPLE OF ANTIQUITY 5 OBELISK NOT ACCESSIBLE 6 CHURCH OF PEACE 16 BELVEDERE ON KLAUSBERG HILL NOT ACCESSIBLE 7 FIRST RONDEL 17 ORANGERY PALACE 8 GREAT FOUNTAIN 18 THE NEW CHAMBERS OF SANSSOUCI 9 CHINESE HOUSE 19 HISTORIC MILL H 10 ROMAN BATHS H Kaiser-Friedrich-Str. H Neuer Garten, Pfingstberg 11 CHARLOTTENHOF VILLA H Bor nst edte r St r. H An der Ora INFORMATION / LOUNGING LAWN TRAM STOP nge Paradiesgarten rie VISITOR CENTER (Universität Potsdam) tor. Mühle H r His BARRIER-FREE ACCESSIBILITY BUS STOP H Zu Voltaireweg ACCESSIBLE TOILET Besucherzentrum H Gregor-Mendel-Str. TICKET SALES ENTRANCE FOR PERSONS BICYCLE ROUTE H Heckentheater Maulbeerallee WITH RESTRICTED MOBILITY, Gruft ATM WITH ASSISTANCE PUSH BICYCLES Jubiläums- Winzerberg terrasse WI-FI ON THIS ROUTE (ENTRANCE AREA ONLY) NOT BARRIER-FREE Sizilianischer Garten ROUTE FOR PERSONS WITH H STORAGE LOCKERS TOILET RESTRICTED MOBILITY Östlicher Lustgarten alais RESTAURANT ACCESSIBLE TOILET SHUTTLE SERVICE ROUTE Hauptallee Hauptallee Hauptallee H SEASONAL AmP Neuen CAFÉ / SNACK BAR TRAIN STATION H SHUTTLE SERVICE STOP MUSEUM SHOP TAXI STAND SEASONAL Schopenh H WI-FI BUS PARKING LOT VIEWPOINT Marlygarten Ökonomieweg Ökonomieweg auer DEFIBRILLATOR CAR PARKING LOT S Grünes Gitter str. S Allee nach Sanssouci Besucherzentrum Parkgraben S Am Grünen Gitter H H Luisenplatz H DISTANCES 13 H SANSSOUCI PALACE VIA THE GREAT FOUNTAIN TO THE NEW PALACE : CA. -

Travel with the Metropolitan Museum of Art

BBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBB Travel with Met Classics The Met BBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBB May 9–15, 2022 Berlin with Christopher Noey Lecturer BBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBB Berlin Dear Members and Friends of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Berlin pulses with creativity and imagination, standing at the forefront of Europe’s art world. Since the fall of the Wall, the German capital’s evolution has been remarkable. Industrial spaces now host an abundance of striking private art galleries, and the city’s landscapes have been redefined by cutting-edge architecture and thought-provoking monuments. I invite you to join me in May 2022 for a five-day, behind-the-scenes immersion into the best Berlin has to offer, from its historic museum collections and lavish Prussian palaces to its elegant opera houses and electrifying contemporary art scene. We will begin with an exploration of the city’s Cold War past, and lunch atop the famous Reichstag. On Museum Island, we -

8 Days Highlights of Germany

HIGHLIGHTS OF GERMANY | 31 HIGHLIGHTS OF GERMANY BERLIN MUNICH 8 DAYS Germany has been ranked one of the top destinations to visit for 2020. On this 8-day journey including Berlin from and Munich, explore magnificent castles, modern skyscrapers and the stunning Bavarian Alps. Travel in comfort by train admiring the changing landscapes and appreciating the rich history on display throughout $3 ,19 9 your journey. CAD$, PP, DBL. OCC. TOUR OVERVIEW Total 7 nights accommodation; Day 1 Day 6 B 4-Star hotels BERLIN Arrival in Berlin, the capital and largest city in Germany. MUNICH Breakfast at the hotel. Begin your half-day, private Welcome by our local representatives and transfer to your hotel. city tour of Munich, the home of the famous Oktoberfest. Start 4 nights in Berlin 3 nights in Munich Scandic Berlin Potsdamer Platz, Superior Room at the Karlstor, passing the church of St. Michael, the Marienplatz Square with City Hall and its famous Carillon, Private transfers to and from Day 2 B the Frauenkirche and many other attractions of the historic airports and train station center. We recommend a tour of Munich’s old town and the BERLIN After breakfast, begin your private morning city tour of history of beer brewing. Enjoy the rest of your day at leisure First-Class Train Tickets: Berlin, providing an overview of both the historic and perhaps to do some shopping in the area of Alexanderplatz Berlin – Munich contemporary aspects of the city including numerous famous or Friedrichstrasse. Eden Hotel Wolff monuments. See the Kurfürstendamm, the Kaiser-Wilhelm- Private city tours with Gedächtniskirche church, Charlottenburg Castle, the English-speaking Guide Siegessäule, the Government district (Regierungsviertel), the Day 7 B Brandenburg Gate, the Holocaust Memorial, the remains of MUNICH Breakfast at the hotel. -

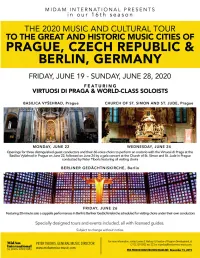

Published on February 11, 2019; Disregard All Previous Documents 1

Subject to change without notice; Published on February 11, 2019; disregard all previous documents 1 Subject to change without notice; Published on February 11, 2019; disregard all previous documents 2 Subject to change without notice; Published on February 11, 2019; disregard all previous documents 3 Subject to change without notice; Published on February 11, 2019; disregard all previous documents 4 2020 Music Tour to Prague and Berlin Registration Deadline: November 15, 2020 Two performances in The Basilica Vyšehrad and The Church of St. Simon and St. Jude On Monday, June 22 and Wednesday, June 24 Mozart’s Vesperae solennes de confessore, K. 339 Earl Rivers, conductor College-Conservatory of Music University of Cincinnati, Ohio And Director of Music Knox Presbyterian Church, Cincinnati, Ohio Virtuosi di Praga Oldřich Vlček, Artistic Director & World-class soloists PLUS Friday, June 26 An a cappella solo performance opportunity by visiting choirs In Berliner Gedächtniskirche A minimum of three groups must agree to perform for this concert to go forward. The Basilica Vyšehrad The Church of St. Simon and St. Jude Berliner Gedächtniskirche MidAm International, Inc. · 39 Broadway, Suite 3600 (36th FL) · New York, NY 10006 Tel. (212) 239-0205 · Fax (212) 563-5587 · www.midamerica-music.com Subject to change without notice; Published on February 11, 2019; disregard all previous documents 5 2020 MUSIC TOUR TO PRAGUE AND BERLIN: Itinerary Day 1 – Friday, June 19, 2020 – Arrive Prague • Arrive in Prague. MidAm International, Inc. staff and The Columbus Welcome Management staff will meet you at the airport and transfer you to Hotel Don Giovanni (http://www.hotelgiovanni.cz/en) for check-in. -

Berlin Travel Guide

BERLIN TRAVEL GUIDE Made by Dorling Kindersley 29. March 2010 PERSONAL GUIDES POWERED BY traveldk.com 1 Highlights Berlin Travel Guide Highlights Brandenburger Tor & Pariser Platz The best known of Berlin’s symbols, the Brandenburg Gate stands proudly in the middle of Pariser Platz, asserting itself against the hyper-modern embassy buildings that now surround it. Crowned by its triumphant Quadriga sculpture, the famous Gate has long been a focal point in Berlin’s history: rulers and statesmen, military parades and demonstrations – all have felt compelled to march through the Brandenburger Tor. www.berlin.de/tourismus/sehenswuerdigkeiten.en/00022.html For more on historical architecture in Berlin (see Historic Buildings) restaurant and a souvenir shop around a pleasantly Top 10 Sights shaded courtyard. Brandenburger Tor Eugen-Gutmann-Haus 1 Since its restoration in 2002, Berlin’s symbol is now 8 With its clean lines, the Dresdner Bank, built in the lit up more brightly than ever before. Built by Carl G round by the Hamburg architects’ team gmp in 1996–7, Langhans in 1789–91 and modelled on the temple recalls the style of the New Sobriety movement of the porticos of ancient Athens, the Gate has, since the 19th 1920s. In front of the building, which serves as the Berlin century, been the backdrop for many events in the city’s headquarters of the Dresdner Bank, stands the famous turbulent history. original street sign for the Pariser Platz. Quadriga Haus Liebermann 2 The sculpture, 6 m (20 ft) high above the Gate, was 9 Josef Paul Kleihues erected this building at the north created in 1794 by Johann Gottfried Schadow as a end of the Brandenburger Tor in 1996–8, faithfully symbol of peace. -

ROSTOCK, GERMANY Disembark: 0800 Monday, September 08 Onboard: 1800 Tuesday, September 09

ROSTOCK, GERMANY Disembark: 0800 Monday, September 08 Onboard: 1800 Tuesday, September 09 Brief Overview: Right off of the Northern coast of Germany situated just inland from the Baltic Sea lays Rostock, the largest city in the German state of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern. The city was founded in 1200 by German merchants and craftsmen and has since grown to be a large seaport. The city of Rostock is home to one of the oldest universities in the world, the University of Rostock founded in 1419. In the city proper you can see brick gothic buildings from the 13th century, baroque facades from the 18th century and carefully restored gables from the 15th and 16th century, all standing side-by- side in the Neuer Markt. Running east, and connecting the university to Neuer Markt is the pedestrian precinct known as Kröpeliner Straße. Kröpeliner Straße is a central location from which you can visit the Convent of St. Catherine and St. Nicholas Church, the oldest church in Rostock. Rostock is also a great base location for your adventures because of the ease with which you may venture to many of Germany’s most exciting and well-known destinations. Out of town: Berlin is just a three-hour trip away with much to do and see. Explore the city’s dark recent history and numerous memorials, including the Holocaust Memorial and the concentration camps that lay just outside of Berlin. There is much to do and see in this vibrant and modern-day culture. Immerse yourself in the energetic art scene that Berlin has become widely known for, ranging from its street art to its fabulous art collections housed in museums such as the Pergamon. -

Berlin Top Sights • Local Life • Made Easy

BERLIN TOP SIGHTS • LOCAL LIFE • MADE EASY Andrea Schulte-Peevers -quickstart-title-pg-pk-bln3.indd 1 27/01/2012 11:41:52 AM In This Book 18 Neighbourhoods 19 16 Need to Know 17 11 11 11 Prenzlauer Berg11 Scheunenviertel & (p110) Before You Go Arriving in Berlin Getting Around 1111 Berlin 1111 Around (p72) This charismatic Need to Arrival options in Berlin are changing in Berlin has an extensive and fairly reliable 1111 The maze-like historic neighbourhood entices Your Daily Budget 1111 2012 with the opening of Berlin Brandenburg public transport system consisting of the 1111 Jewish Quarter is with fun shopping, 1111111 1111 Neighbourhoods Prenzlauer Berg Museum Island & Know Budget less than €50 Airport (near the current Schönefeld airport) U-Bahn (underground/subway), S-Bahn 1111 fashionista central and gorgeous townhouses, 1111 1111 QuickStart cosy cafes and a 1111111Alexanderplatz1111 in June and the subsequent closure of Tegel (light rail), buses and trams. One ticket is X Dorm beds €10–20 Reichstag & also teems with hip bars 1111 1111 fabulous flea market. 1111111(p40) 1111 and the old Schönefeld airports. If arriving good for all forms of transport. For trip Unter den Linden and restaurants. For more information, see Survival X Self-catering or fast food by train, Hauptbahnhof is the central station. planning, see www.bvg.de. 1111Gawk at a pirate's1111 (p22) 1Top Sights 111 Guide (p 173 ). chest of treasure from Berlin's historic hub # Museum Island Midrange €50–150 From Berlin-Tegel Airport U-Bahn Gedenkstätte Berliner EGedenkstätte ancient civilisations A delivers great views, Currency X Double room €80–120 The most efficient way to travel around Mauer Berliner Mauer guarded by the soaring Destination Best Transport iconic landmarks and TV Tower on socialist- Euro (€) X Two-course dinner with wine €30 Berlin is by U-Bahn, which runs from 4am Alexanderplatz TXL express bus the city's most beautiful until about 12.30am and throughout the styled Alexanderplatz. -

Advisory Body Evaluation (ICOMOS)

ICOMOS INTERNATIONAL COUNCIL ON MONUMENTS AND SITES CONSEIL INTERNATIONAL DES MONUMENTS ET DES SITES CONSEJO INTERNACIONAL DE MONUMENTOS Y SITIOS MDIOlYHAPOnHbIti CO BET ITO BOITPOCAM ITAM5ITHIiKOB Ii llOCTOITPIiMEqATEJIbHbIX MECT WORLD HERITAGE LIST A) IDENTIFICATION Nomination : Chateaux and Parks of Potsdam-Sanssouci Location : District of Potsdam State party : German Democratic Republic Date: 13 October, 1989 B) ICOMOS RECOMMENDATION That this cultural property be included on the World Heritage List on the basis of Criteria I, II and IV. C) JUSTIFICATION Ten kilometers south-west of Berlin in an attractive post-Ice Age landscape where eroded hills and morainic deposits stopped the River Havel's westward course, forming a series of lakes, Potsdam, mentioned first in the 10th century, acquired some importance only under the Great Elector of Brandenburg, Frederick William (1620-1688). In 1661 he established a residence there where, in 1685, he signed the Edict of Potsdam, whose political importance needs no comment. Potsdam housed a small garrison from 1640 on. The site's military function was strengthened by the young Prussian monarchy, especially once Frederick William I ascended to the throne in 1713. To populate the town, the "Sergeant King", the veritable architect of Prussian might, called upon immigration. At his death in 1740, Potsdam totaled 11,708 inhabitants living in 1,154 buildings that were the result of two successive urbanization programs. Under Frederick II the Great (1712-1786), Potsdam changed radically. The new king -his love of literature and the arts brought him into conflict with his father and his relationship with French and English philosophers gave him a reputation as a follower of the "Enlightenment"- wished to establish next to the garrison town and settlement colony of the "Sergeant King", a "Prussian Versailles", which was to be his main residence. -

Final Unformatted Bilbio Revised

Université de Montréal Urban planning and identity: the evolution of Berlin’s Nikolaiviertel par Mathieu Robinson Département de littératures et langues du monde, Faculté des arts et des sciences Mémoire présenté en vue de l’obtention du grade de Maîtrise ès arts en études allemandes Mars 2020 © Mathieu Robinson, 2020 RÉSUMÉ Le quartier du Nikolaiviertel, situé au centre de Berlin, est considéré comme le lieu de naissance de la ville remontant au 13e siècle. Malgré son charme médiéval, le quartier fut construit dans les années 1980. Ce dernier a été conçu comme moyen d’enraciner l’identité est-allemande dans le passé afin de se démarquer culturellement de ces voisins à l’ouest, et ce, à une époque de détente et de rapprochement entre la République démocratique allemande (RDA) et la République fédérale d’Allemagne (RFA). Depuis la construction du quartier, Berlin a connu une transformation exceptionnelle; elle est passée de ville scindée à la capitale d’un des pays les plus puissants au monde. La question se pose : quelle est l’importance de Nikolaiviertel, ce projet identitaire est-allemand, dans le Berlin réunifié d’aujourd’hui ? Ce projet part de l’hypothèse que le quartier est beaucoup plus important que laisse croire sa réputation de simple site touristique kitsch. En étudiant les rôles que joue le Nikolaiviertel dans la ville d’aujourd’hui, cette recherche démontre que le quartier est un important lieu identitaire au centre de la ville puisqu’il représente simultanément une multiplicité d’identités indissociables à Berlin, c’est-à-dire une identité locale berlinoise, une identité nationale est-allemande et une identité supranationale européenne. -

"Sanssouci, Potsdam" Pen of the Year 2015

P RESSEINFORMATION · P RESS RELEASE COMMUNIQUÉ DE P RESSE · COMUNICADO DE P RENSA INFORMAÇ ÕES P AR A A I MPRENSA "Sanssouci, Potsdam" Pen of the Year 2015 The new limited edition "Pen of the Year" is inspired by the fascinating architecture of the New Palace of Sanssouci which was built according to plans by Frederick II. Produced by the hand of a skilled master The creation of the Pen of the Year demands the highest standards of craftsmanship. For the latest edition, we were able to commission the Herbert Stephan gemstone manufactory. It carries on the great tradition of the Idar Oberstein gemstone workshop which dates back to the 15th century and is still of world renown. The manufactory's masters impressively demonstrated their unparalleled skill with this year's Pen of the Year: Its platinum-plated barrel and cap are adorned by four green Silesian serpentines and a Russian smoky quartz – both ground and polished by hand. The special edition combines 24-carat gold plating with green serpentine and rare chrysoprase, Frederick's favourite natural stone. Chrysoprase has not been mined for many years and is only available on the antique stone market. The special edition is limited to 150 fountain pens and 30 rollerball pens. The platinum plated fountain pen is limited to 1,000 units, the rollerball pen to 300 units. Each writing instrument is individually numbered and comes in a highly polished, deep-black wooden case. It includes a certificate personally signed by the manufacturer Herbert Stephan attesting to the authenticity of the natural stones. -

The Flutist of Sanssouci: King Frederick “The Great” As Performer and Composer

VOLUMEXXXVIII , NO . 1 F ALL 2 0 1 2 THE lut i st QUARTERLY The Flutist of Sanssouci: King Frederick “the Great” as Performer and Composer The Remarkable Career of Walfrid Kujala Greg Pattillo’s Three Beats for Beatbox Flute THEOFFICIALMAGAZINEOFTHENATIONALFLUTEASSOCIATION, INC Table of CONTENTSTHE FLUTIST QUARTERLY VOLUME XXXVIII, NO. 1 FALL 2012 DEPARTMENTS 11 From the Chair 49 Notes from Around the World 13 From the Editor 52 New Products 14 High Notes 58 Reviews 73 NFA Office, Coordinators, 39 Across the Miles Committee Chairs 42 From the Research Chair 76 Where Are They Now? 44 Honor Roll of Donors to the NFA 77 Index of Advertisers 18 FEATURES 18 The Flutist of Sanssouci: King Frederick “the Great” as Performer and Composer by Mary Oleskiewicz In this anniversary year of the renowned military king’s birth in 1712, noted flute historian and scholar Mary Oleskiewicz explores the musical sensitivity and prowess of composer and flutist Frederick II. The article is based upon research from the author’s first edition of sonatas by Frederick, released this year, of historic recordings made at the king’s beloved retreat at Sanssouci. 28 The Remarkable Career of Walfrid Kujala by John Bailey Wally Kujala’s curious mind, even-tempered teaching manner, and superior performance skills have earned him a long list of followers, friends, and fellow colleagues—as evidenced at Northwestern’s 2012 gala retirement celebration featuring the unveiling of a portrait painted by longtime NFA friend Patti Adams and the world premiere of a work composed for him by Joseph Schwantner. 28 34 Three Beats For Beatbox Flute: A Chat with Greg Pattillo by Ronda Benson Ford At the 2011 convention in Charlotte, Ronda Benson Ford spoke with beatbox flutist Greg Pattillo, whom the NFA had commissioned to write a work for the 2012 competition, about his piece and his process.