The Dystonias

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

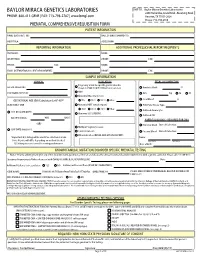

Prenatal Testing Requisition Form

BAYLOR MIRACA GENETICS LABORATORIES SHIP TO: Baylor Miraca Genetics Laboratories 2450 Holcombe, Grand Blvd. -Receiving Dock PHONE: 800-411-GENE | FAX: 713-798-2787 | www.bmgl.com Houston, TX 77021-2024 Phone: 713-798-6555 PRENATAL COMPREHENSIVE REQUISITION FORM PATIENT INFORMATION NAME (LAST,FIRST, MI): DATE OF BIRTH (MM/DD/YY): HOSPITAL#: ACCESSION#: REPORTING INFORMATION ADDITIONAL PROFESSIONAL REPORT RECIPIENTS PHYSICIAN: NAME: INSTITUTION: PHONE: FAX: PHONE: FAX: NAME: EMAIL (INTERNATIONAL CLIENT REQUIREMENT): PHONE: FAX: SAMPLE INFORMATION CLINICAL INDICATION FETAL SPECIMEN TYPE Pregnancy at risk for specific genetic disorder DATE OF COLLECTION: (Complete FAMILIAL MUTATION information below) Amniotic Fluid: cc AMA PERFORMING PHYSICIAN: CVS: mg TA TC Abnormal Maternal Screen: Fetal Blood: cc GESTATIONAL AGE (GA) Calculation for AF-AFP* NTD TRI 21 TRI 18 Other: SELECT ONLY ONE: Abnormal NIPT (attach report): POC/Fetal Tissue, Type: TRI 21 TRI 13 TRI 18 Other: Cultured Amniocytes U/S DATE (MM/DD/YY): Abnormal U/S (SPECIFY): Cultured CVS GA ON U/S DATE: WKS DAYS PARENTAL BLOODS - REQUIRED FOR CMA -OR- Maternal Blood Date of Collection: Multiple Pregnancy Losses LMP DATE (MM/DD/YY): Parental Concern Paternal Blood Date of Collection: Other Indication (DETAIL AND ATTACH REPORT): *Important: U/S dating will be used if no selection is made. Name: Note: Results will differ depending on method checked. Last Name First Name U/S dating increases overall screening performance. Date of Birth: KNOWN FAMILIAL MUTATION/DISORDER SPECIFIC PRENATAL TESTING Notice: Prior to ordering testing for any of the disorders listed, you must call the lab and discuss the clinical history and sample requirements with a genetic counselor. -

NGS Panels 2020

NGS Panels 2020 BENEFIT FROM OUR MEDICAL EXPERTISE AND STREAMLINED GENETIC TESTING NGS Panels 2020 Benefit from our Medical Expertise and Streamlined Genetic Testing CENTOGENE is fully committed to bringing the best possible diagnostic solutions to our patients and their families. We always strive to incorporate the latest in-house findings and medical research in our products to improve and ease the diagnostic odyssey of rare disease patients. To reflect the fast-growing knowledge of complex associations of genes with diseases as well as to maximize clinical sensitivity, we have updated and significantly redesigned our Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) gene panels. The gene composition of each panel has been revised to meet the latest gene discoveries as well as to provide the highest clinical validity. Additionally, we have minimized complexity and removed redundancy in the panel portfolio by creating phenotype-directed diagnostic panels, which are the most comprehensive and include all relevant genes necessary for differential diagnosis of syndromes with overlapping phenotype, therefore allowing the diagnosis of diseases that otherwise would be missed. This principle increases the clinical utility, de-risks panel choice, increases cost-effectiveness, and ultimately simplifies the diagnostic process. When choosing one of our NGS panels, feel confident that you will receive high-quality sequencing combined with best data analysis and interpretation, which are documented in comprehensive medical reports. As always, CENTOGENE and our Customer -

The Genetics of Primary Dystonias and Related Disorders

Brain (2002), 125, 695±721 INVITED REVIEW The genetics of primary dystonias and related disorders Andrea H. NeÂmeth The Wellcome Trust Centre for Human Genetics, Roosevelt Drive, Headington, Oxford OX3 7BN, UK E-mail: [email protected] Summary Dystonias are a heterogeneous group of disorders which dystonia (DYT1), focal dystonias (DYT7) and mixed dys- are known to have a strong inherited basis. This review tonias (DYT6 and DYT13), dopa-responsive dystonia, details recent advances in our understanding of the gen- myoclonus dystonia, rapid-onset dystonia parkinsonism, etic basis of dystonias, including the primary dystonias, Fahr disease, Aicardi±Goutieres syndrome, Haller- the `dystonia-plus' syndromes and heredodegenerative vorden±Spatz syndrome, X-linked dystonia parkin- disorders. The review focuses particularly on clinical sonism, deafness±dystonia syndrome, mitochondrial and genetic features and molecular mechanisms. dystonias, neuroacanthocytosis and the paroxysmal dys- Conditions discussed in detail include idiopathic torsion tonias/dyskinesias. Keywords: dystonia; L-dopa; parkinsonism; myoclonus; mitochondria Abbreviations: DRD = dopa-responsive dystonia; ITD = idiopathic torsion dystonia; PDJ = juvenile onset Parkinson's disease; PKC = paroxysmal kinesigenic choreoathetosis; PNKD = paroxysmal non-kinesigenic dyskinesia; TH = tyrosine hydroxylase Introduction Dystonia is a disorder of movement caused by `involuntary, (Fahn et al., 1998). Clinically, this is useful because onset of sustained muscle contractions affecting one or more sites of dystonia in the limbs, particularly the legs, is more likely to the body, frequently causing twisting and repetitive move- be associated with spread to other body parts and has ments, or abnormal postures' (Fahn et al., 1987, 1998). The important implications for treatment, management and prog- genetic contribution to the development of dystonia has been nosis, since generalized dystonia is usually much more recognized for many years, but it is only recently that some of disabling. -

Genetic Testing Medical Policy – Genetics

Genetic Testing Medical Policy – Genetics Please complete all appropriate questions fully. Suggested medical record documentation: • Current History & Physical • Progress Notes • Family Genetic History • Genetic Counseling Evaluation *Failure to include suggested medical record documentation may result in delay or possible denial of request. PATIENT INFORMATION Name: Member ID: Group ID: PROCEDURE INFORMATION Genetic Counseling performed: c Yes c No **Please check the requested analyte(s), identify number of units requested, and provide indication/rationale for testing. 81400 Molecular Pathology Level 1 Units _____ c ACADM (acyl-CoA dehydrogenase, C-4 to C-12 straight chain, MCAD) (e.g., medium chain acyl dehydrogenase deficiency), K304E variant _____ c ACE (angiotensin converting enzyme) (e.g., hereditary blood pressure regulation), insertion/deletion variant _____ c AGTR1 (angiotensin II receptor, type 1) (e.g., essential hypertension), 1166A>C variant _____ c BCKDHA (branched chain keto acid dehydrogenase E1, alpha polypeptide) (e.g., maple syrup urine disease, type 1A), Y438N variant _____ c CCR5 (chemokine C-C motif receptor 5) (e.g., HIV resistance), 32-bp deletion mutation/794 825del32 deletion _____ c CLRN1 (clarin 1) (e.g., Usher syndrome, type 3), N48K variant _____ c DPYD (dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase) (e.g., 5-fluorouracil/5-FU and capecitabine drug metabolism), IVS14+1G>A variant _____ c F13B (coagulation factor XIII, B polypeptide) (e.g., hereditary hypercoagulability), V34L variant _____ c F2 (coagulation factor 2) (e.g., -

Proquest Dissertations

mn u Ottawa l.'Univcrsilc can.ifficn/ic Canada's university FACULTE DES ETUDES SUPERIEURES 11=1 FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND ET POSTOCTORALES U Ottawa POSDOCTORAL STUDIES L'Urriversittf canadienne (Canada's university Fabin Han AUTEUR DE LA THESE / AUTHOR OF THESIS Ph.D. (Microbiology and Immunology) GRADE/DEGREE Department of Biochemistry, Microbiology and Immunology Characterization of the Genes for Myoclonus-Dystonia TITRE DE LA THESE / TITLE OF THESIS Dennis Bulman EXAMINATEURS (EXAMINATRICES) DE LA THESE /THESIS EXAMINERS John Bell Peter Ray Robert Korneluk Catherine Tsilfidis Gary W. Slater. Le Doyen de la Faculte des etudes superieures et postdoctorales / Dean of the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies Characterization of the Genes for Myoclonus-Dystonia By Fabin Han Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctorate of Philosophy Department of Biochemistry, Microbiology and Immunology, Graduate Collaborative Program in Human and Molecular Genetics, Faculty of Medicine University of Ottawa Copyright by Fabin Han, 2007 Ottawa, Canada Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-49354-0 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-49354-0 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing -

Multitarget Deep Brain Stimulation for Clinically Complex Movement Disorders

CASE REPORT Multitarget deep brain stimulation for clinically complex movement disorders Tariq Parker, MRCS, Ashley L. B. Raghu, BSc(Hons), James J. FitzGerald, FRCS(SN), Alexander L. Green, FRCS(SN), and Tipu Z. Aziz, FMedSci Oxford Functional Neurosurgery, Nuffield Department of Surgical Sciences, University of Oxford, United Kingdom Deep brain stimulation (DBS) of single-target nuclei has produced remarkable functional outcomes in a number of move- ment disorders such as Parkinson’s disease, essential tremor, and dystonia. While these benefits are well established, DBS efficacy and strategy for unusual, unclassified movement disorder syndromes is less clear. A strategy of dual pal- lidal and thalamic electrode placement is a rational approach in such cases where there is profound, medically refractory functional impairment. The authors report a series of such cases: midbrain cavernoma hemorrhage with olivary hyper- trophy, spinocerebellar ataxia-like disorder of probable genetic origin, Holmes tremor secondary to brainstem stroke, and hemiballismus due to traumatic thalamic hemorrhage, all treated by dual pallidal and thalamic DBS. All patients demon- strated robust benefit from DBS, maintained in long-term follow-up. This series demonstrates the flexibility and efficacy, but also the limitations, of dual thalamo-pallidal stimulation for managing axial and limb symptoms of tremors, dystonia, chorea, and hemiballismus in patients with complex movement disorders. https://thejns.org/doi/abs/10.3171/2019.11.JNS192224 KEYWORDS deep brain stimulation; dystonia; essential tremor; thalamus; globus pallidus; functional neurosurgery EEP brain stimulation (DBS) surgery for the treat- Her condition progressed to developing speech difficul- ment of movement disorders usually employs stim- ties, left-sided one-and-a-half syndrome, and a bilateral ulation at a single site in one or both hemispheres. -

Alcohol-Responsive Writer's Cramp

□ CASE REPORT □ Alcohol-Responsive Writer’s Cramp Sung-Chul Lim 1, Joong-Seok Kim 1, Jae-Young An 1 and Sa Yoon Kang 2 Abstract Writer’s cramp is a rare movement disorder of unknown etiology, in which a cramp is elicited primarily or exclusively with writing. We describe a patient with primary writer’s cramp that was completely improved by drinking a small amount of alcohol. Although it is unclear how “alcohol” ameliorated the dystonia, this case suggests that alcohol might reverse the pathophysiologic changes in the entire basal ganglia circuit. In addi- tion, we cannot rule out the possibility that the anxiolytic influence of alcohol may contribute to the benefi- cial effects on dystonia. Key words: writer’s cramp, alcohol (Intern Med 51: 99-101, 2012) (DOI: 10.2169/internalmedicine.51.6322) patient reported her symptoms were temporally relieved by Introduction drinking a small amount of alcohol. The patient was never exposed to neuroleptics nor did she have a family history of Writer’s cramp is the most common task-specific action dystonia. dystonia, elicited primarily or exclusively with writing. In There was no dystonia or myoclonus of the limbs, with most cases, this disorder is associated with discomfort, fre- routine movement. Examination of the patient during hand- quently includes other tasks, and often produces significant writing showed a combination of excessive squeezing of the disability with no identifiable drug responses (1). In this re- pen with the thumb and index finger, and involuntary exten- port, we present a 43-year-old woman with a 20-year history sion of the wrist. -

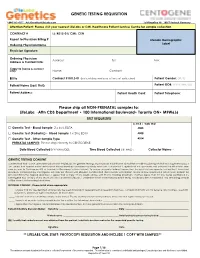

GENETIC TESTING REQUISITION Please Ship All NON-PRENATAL

GENETIC TESTING REQUISITION 1-844-363-4357· [email protected] Schillingallee 68 · 18057 Rostock Germany Attention Patient: Please visit your nearest LifeLabs or CML Healthcare Patient Service Centre for sample collection CONTRACT # LL: K012-01/ CML: CEN Report to Physician Billing # LifeLabs Demographic Label Ordering Physician Name Physician Signature: Ordering Physician Address: Tel: Fax: Address & Contact Info: Copy to (name & contact info): Name: Contact: Bill to Contract # K012-01 (patient does not pay at time of collection) Patient Gender: (M/F) Patient Name (Last, First): Patient DOB: (YYYY/MM/DD) Patient Address: Patient Health Card: Patient Telephone: Please ship all NON-PRENATAL samples to: LifeLabs · Attn CDS Department • 100 International Boulevard• Toronto ON• M9W6J6 TEST REQUESTED LL TR # / CML TC# □ Genetic Test - Blood Sample 2 x 4mL EDTA 4005 □ Genetic Test (Pediatric) - Blood Sample 1 x 2mL EDTA 4008 □ Genetic Test - Other Sample Type 4014 PRENATAL SAMPLES: Please ship directly to CENTOGENE. Date Blood Collected (YYYY/MM/DD): ___________ Time Blood Collected (HH:MM)) :________ Collector Name: - ___________________ GENETIC TESTING CONSENT I understand that a DNA specimen will be sent to LifeLabs for genetic testing. My physician has told me about the condition(s) being tested and its genetic basis. I am aware that correct information about the relationships between my family members is important. I agree that my specimen and personal health information may be sent to Centogene AG at their lab in Germany (address below). To ensure accurate testing, I agree that the results of any genetic testing that I have had previously completed by Centogene AG may be shared with LifeLabs. -

Factors Regulating the Function and Assembly of the Sarcoglycan Complex in Brain

Factors regulating the function and assembly of the sarcoglycan complex in brain A thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Cardiff University School of Medicine Francesca Carlisle 2016 Supervised by Professor Derek Blake and Professor Anthony Isles Thesis summary Myoclonus dystonia (MD) is a neurogenic movement disorder that can be caused by mutations in the SGCE gene encoding ε-sarcoglycan. ε-sarcoglycan belongs to the sarcoglycan family of cell surface-localised, single-pass transmembrane proteins originally identified in muscle where they form a heterotetrameric subcomplex of the dystrophin- associated glycoprotein complex (DGC). Mutations in the SGCA, SGCB, SGCG and SGCD genes encoding α-, β-, γ- and δ-sarcoglycan cause limb-girdle muscular dystrophy (LGMD). There is no phenotypic overlap between MD and LGMD. LGMD-associated sarcoglycan mutations impair trafficking of the entire sarcoglycan complex to the cell surface and destabilise the DGC in muscle, while MD-associated mutations typically result in loss of ε- sarcoglycan from the cell surface. This suggests cell surface ε-sarcoglycan but not other sarcoglycans is required for normal brain function. To gain insight into ε-sarcoglycan’s function(s) in the brain, immunoaffinity purification was used to identify ε-sarcoglycan- interacting proteins. Ubiquitous and brain-specific ε-sarcoglycan isoforms co-purified with three other sarcoglycans including ζ-sarcoglycan (encoded by SGCZ) from the brain. Incorporation of an LGMD-associated β-sarcoglycan mutant into the brain sarcoglycan complex impaired the formation of the βδ-sarcoglycan core but failed to abrogate the association and trafficking of ε- and ζ-sarcoglycan in heterologous cells. Both ε-sarcoglycan isoforms also co-purified with β-dystroglycan, indicating inclusion in DGC-like complexes. -

A Review of Psychiatric Co-Morbidity Described in Genetic and Immune Mediated Movement Disorders

Psychiatric co-morbidity in Movement Disorders Peall et al 2017 A review of psychiatric co-morbidity described in genetic and immune mediated movement disorders KJ Peall,a* MS Lorentzos,b* I Heyman,c,d MAJ Tijssen (MD, PhD),e MJ Owen,a RC Dale,b+ MA Kuriand,f+ aMRC Centre for Neuropsychiatric Genetics and Genomics, Hadyn Ellis Building, Heath Park, Cardiff, UK CF24 4HQ bMovement Disorders Clinic, the Children's Hospital at Westmead, University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia cDepartment of Psychological Medicine, Great Ormond Street Hospital, London, UK dDevelopmental Neurosciences Programme, UCL-Institute of Child Health, London, UK eDepartment of Neurology, University of Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands fDepartment of Neurology, Great Ormond Street Hospital, London, UK *These authors contributed equally to the manuscript +These authors contributed equally to the manuscript Corresponding authors: Dr Kathryn Peall, MRC Centre for Neuropsychiatric Genetics and Genomics, Hadyn Ellis Building, Heath Park, Cardiff, UK CF24 4HQ. Email: [email protected]; Telephone: 029 20 743454 Dr Manju Kurian, Developmental Neurosciences Programme, UCL-Institute of Child Health, London, UK. Email: [email protected]; Telephone: 020 7405 9200 ext. 8308 Psychiatric co-morbidity in Movement Disorders Peall et al 2017 Abstract Psychiatric symptoms are an increasingly recognised feature of movement disorders. Recent identification of causative genes and autoantibodies has allowed detailed analysis of aetiologically homogenous subgroups, thereby enabling determination of the spectrum of psychiatric symptoms in these disorders. This review evaluates the incidence and type of psychiatric symptoms encountered in patients with movement disorders. A broad spectrum of psychiatric symptoms was identified across all subtypes of movement disorder, with depression, generalised anxiety disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder being most common. -

Research Advances on the Treatment of Myoclonus-Dystonia Syndrome

ogy & N ol eu ur e ro N p h f y o s l Jie, J Neurol Neurophysiol 2014, 5:5 i o a l n o r g u y o DOI: 10.4172/2155-9562.1000228 J Journal of Neurology & Neurophysiology ISSN: 2155-9562 Review Article Open Access Research Advances on the Treatment of Myoclonus-Dystonia Syndrome Jie Fu* Department of Neurology, The Hospital Affiliated of Luzhou Medical College, Sichuan, China *Corresponding author: Jie Fu, Department of Neurology, The Hospital Affiliated of Luzhou Medical College. Jiangyang Region, 25 Taiping Street, Luzhou, 646000, Sichuan, China, Tel: 8615181960975; E-mail: [email protected] Received date: July 13, 2014, Accepted date: Sep 06, 2014, Published date: Sep 15, 2014 Copyright: © 2014 Fu J, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Abstract Myoclonus-Dystonia Syndrome is a movement disorder characterized by the association of myoclonus and dystonia as the sole or prominent symptoms. Non-motor features may include obsessive-compulsive disorder, depression, anxiety, personality disorders, alcohol abuse, and panic attacks. The pathogenesis of MDS is not very clear, and the current opinions are mainly focus on gene mutations. The diagnosis is mainly based on clinical features, and this disorder is confirmed by gene testing. Myoclonus-Dystonia Syndrome can’t be cured, and the current therapy is mainly aimed to improve the symptoms, which includes medical and surgical treatment. All in all, MDS remains poorly responsive to medical treatment. -

Deep Brain Stimulation for Tremor Associated with Underlying Ataxia Syndromes: a Case Series and Discussion of Issues

Freely available online Articles Deep Brain Stimulation for Tremor Associated with Underlying Ataxia Syndromes: A Case Series and Discussion of Issues 1 1 2 1 2 1 1 Genko Oyama , Amanda Thompson , Kelly D. Foote , Natlada Limotai , Muhammad Abd-El-Barr , Nicholas Maling , Irene A. Malaty , 1 1 1 1,2* Ramon L. Rodriguez , Sankarasubramoney H. Subramony , Tetsuo Ashizawa & Michael S. Okun 1 Department of Neurology, 2 Department of Neurosurgery, University of Florida, Center for Movement Disorders and Neurorestoration, Gainesville, FL, USA Abstract Background: Deep brain stimulation (DBS) has been utilized to treat various symptoms in patients suffering from movement disorders such as Parkinson’s disease, dystonia, and essential tremor. Though ataxia syndromes have not been formally or frequently addressed with DBS, there are patients with ataxia and associated medication refractory tremor or dystonia who may potentially benefit from therapy. Methods: A retrospective database review was performed, searching for cases of ataxia where tremor and/or dystonia were addressed by utilizing DBS at the University of Florida Center for Movement Disorders and Neurorestoration between 2008 and 2011. Five patients were found who had DBS implantation to address either medication refractory tremor or dystonia. The patient’s underlying diagnoses included spinocerebellar ataxia type 2 (SCA2), fragile X associated tremor ataxia syndrome (FXTAS), a case of idiopathic ataxia (ataxia not otherwise specified [NOS]), spinocerebellar ataxia type 17 (SCA17), and a senataxin mutation (SETX). Results: DBS improved medication refractory tremor in the SCA2 and the ataxia NOS patients. The outcome for the FXTAS patient was poor. DBS improved dystonia in the SCA17 and SETX patients, although dystonia did not improve in the lower extremities of the SCA17 patient.