Spelling Reform Anthology Edited by Newell W. Tune §6. Which Way To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNIVERSITY of STIRLING Kenneth Pardey the WELFARE of the VISUALLY HANDICAPPED in the UNITED KINGDOM

UNIVERSITY OF STIRLING Kenneth Pardey THE WELFARE OF THE VISUALLY HANDICAPPED IN THE UNITED KINGDOM 'Submitted for the degree of Ph.D. December 1986 II CONTENTS Page Acknowledgements III Abstract v 1. Introduction: The history of the welfare of the visually handicapped in the United Kingdom 1 2. Demographic studies of the visually handicapped 161 3. The Royal National Institute for the Blind 189 4. The history and the contribution of braille, moon and talking books 5. St Dunstan's for the war blinded: A history and a critique ,9, 6. Organisations of the visually handicapped 470 7. Social service-a and rehabilitation 520 8. The elderly person with failing vision 610 9. The education of the visually handicapped 691 10. Employment and disability 748 11. Disability and inco1;-~e 825 Bibliography 870 III Acknowledgements I would like to thank the following people who either agreed to be interviewed or helped me to find some useful sources of information: Colin Low, Martin Milligan, Fred Reid, Hans Cohn, Jim Hughes, Janet Lovall, Jill Dean, Joan Hughes, Doreen Chaney and Elaine Bootman of the National Federation of the Blind; Michael Barrett, Tom Parker, Chris Hynes, Pat O'Grady, Frank Mytton, L. J. Isaac, George Slaughter, J. Nor mile and R. 0. Rayner of the National League of the Blind and Disabled; Donald Bell, Tony Aston, George T. Willson, B. T. Gifford, Neville Lawson and Penelope Shore of the Royal National Institute for the Blind; Timothy Cullinan of the Department of Environmental and Preventive Medicine of the Medical College of St -

J33. Journal of the Simplified Spelling

the simplified Founded 1908 in London, England Working for planned change in English spelling for spelling society the benefit of learners and users everywhere Spelcon 2005 Conference Report International English for Global Literacy University of Mannheim – First International Conference, 29th–31st July 2005 Report compiled by Bernadette Hughes, SSS Business Secretary This report was intended to be Journal 33, but was not published at the time. Contents 1. List of Attendees 2. Speaker abstracts 3. Opening of the conference 4. Papers presented 4.1 ‘The worst aspects of English Spelling’ Mrs. Masha Bell 4.2 'Why the Internet age will not accept simplified English spelling’ Dr. Christopher Rollason 4.3 ‘How to prepare for, select and implement a reformed spelling scheme for global English’ Mr. Niall Waldman 4.4 ‘The German spelling reform – An example for the Simplified Spelling Society’ Prof. Gerhard Augst 4.5 ‘Report on the Spelling Bee Contest in Washington Challenges with English spelling while teaching English in Germany’ Mr. Adrian Alphohziel 4.6 ‘Spelling in Indian English – English spelling simplification activity in ‘my’ country: The classroom experience’ Dr. Jenny Bayer 4.7 ‘Strategies for implementing spelling reforms’ Mr. Christopher Jolly 4.8 ‘Centre of power in educational change’ Mrs.Isobel Raven 5. Final announcement by the Chairman 6. De-Briefing session 7. Additional papers 7.1 ‘An alphabet for English – XVIII’ Dr. J Conrad Crown 7.2 ‘Strategies for English spelling reforms’ Dr. L. Devaki 7.3 ‘A practical plan for achieving spelling reform’ Mr. J.Carter 7.4 ‘How systematic repair is possible’ Dr. Valerie Yule, SSS Vice-President 7.5 ‘The case for an International Commission on English Spelling Dr. -

WRITTEN DIALECTS N Spelling Reforms: History N Alternatives by Kenneth H

WRITTEN DIALECTS N Spelling Reforms: History N Alternatives by Kenneth H. Ives © 1979 PROGRESIV PUBLISHR, Chicago IL [112pp. A5 in the printed version] Library of Congress Catalog Card # 78-54745 ISBN 0-89670-004-6 Kenneth Ives is a sociologist and social worker, currently director of research and statistics for a family counseling agency. For the past 10 years he has been studying various aspects of spelling and spelling reform - history, phonetics, readability, writeability, acceptability, and problems of adoption. [Words originally underlined are now in italics. The spellings are as in the original.] Preface In recent years the variety of spoken dialects in English has become a subject for study and appreciation, replacing the former scorn and depreciation for "non-standard English." (Shuy, 1967; Labov, 1970, Butler, 1974) Similarly, differing but consistent ways of writing standard (or even non-standard) English may be viewed as differing written dialects. These include the standard "traditional orthography," (TO), accepted alternate spellings found in dictionaries (Emery, 1973) such as "altho, thru, dropt, fixt, catalog," Pitman's Initial Teaching Alphabet (ITA), and the 50 or more proposals for spelling reform. They also include earlier spellings such as Chaucer used, with the Anglo-Saxon thorn symbol for "th" (still used in Icelandic), and the alphabetic shorthand systems. Our traditional spelling became largely frozen with the rise of printing four centuries ago, and dictionaries and grammars two centuries ago, but our spoken language has had a "great vowel shift" and other changes. Hence the correspondence between our spoken and written dialects has become more complex, irregular, and confusing. -

Colorwatch: Color Perceptual Spatial Tactile Interface for People with Visual Impairments

electronics Article ColorWatch: Color Perceptual Spatial Tactile Interface for People with Visual Impairments Muhammad Shahid Jabbar 1 , Chung-Heon Lee 1 and Jun Dong Cho 1,2,* 1 Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Sungkyunkwan University, Suwon 16419, Gyeonggi-do, Korea; [email protected] (M.S.J.); [email protected] (C.-H.L.) 2 Department of Human ICT Convergence, Sungkyunkwan University, Suwon 16419, Gyeonggi-do, Korea * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Tactile perception enables people with visual impairments (PVI) to engage with artworks and real-life objects at a deeper abstraction level. The development of tactile and multi-sensory assistive technologies has expanded their opportunities to appreciate visual arts. We have developed a tactile interface based on the proposed concept design under considerations of PVI tactile actuation, color perception, and learnability. The proposed interface automatically translates reference colors into spatial tactile patterns. A range of achromatic colors and six prominent basic colors with three levels of chroma and values are considered for the cross-modular association. In addition, an analog tactile color watch design has been proposed. This scheme enables PVI to explore artwork or real-life object color by identifying the reference colors through a color sensor and translating them to the tactile interface. The color identification tests using this scheme on the developed prototype exhibit good recognition accuracy. The workload assessment and usability evaluation for PVI demonstrate promising results. This suggest that the proposed scheme is appropriate for tactile color exploration. Citation: Jabbar, M.S.; Lee, C.-H.; Keywords: color identification; tactile perception; cross modular association; universal design; Cho, J.D. -

Orthographies in Early Modern Europe

Orthographies in Early Modern Europe Orthographies in Early Modern Europe Edited by Susan Baddeley Anja Voeste De Gruyter Mouton An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libra- ries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access. More information about the initiative can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libra- ries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access. More information about the initiative can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org ISBN 978-3-11-021808-4 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-021809-1 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-021806-2 ISSN 0179-0986 e-ISSN 0179-3256 ThisISBN work 978-3-11-021808-4 is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 License, ase-ISBN of February (PDF) 978-3-11-021809-1 23, 2017. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/. e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-021806-2 LibraryISSN 0179-0986 of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Ae-ISSN CIP catalog 0179-3256 record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. ISBN 978-3-11-028812-4 e-ISBNBibliografische 978-3-11-028817-9 Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliogra- fie;This detaillierte work is licensed bibliografische under the DatenCreative sind Commons im Internet Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs über 3.0 License, Libraryhttp://dnb.dnb.deas of February of Congress 23, 2017.abrufbar. -

A.40. GERMAN1 A.40A. Nouns A.40A1. Capitalize All Nouns And

CC:DA/Croissant/2003/1 February 12, 2003 page 1 To: American Library Association ALCTS/CCS Committee on Cataloging: Description and Access From: Charles R. Croissant, Saint Louis University John Hostage, Harvard Law School Library Subject: Revision of AACR2 Appendix A, Capitalization, A.40. German. Background: After several decades of work by an international commission of representatives from the German-speaking nations, a new set of rules for German orthography, including capitalization, was officially accepted by the governments of these countries at a meeting in Vienna on July 1, 1996. The rules were officially introduced on August 1, 1998. A period of transition, during which both the old and the new orthography are valid, is scheduled to end on August 1, 2005. Although the new orthography cannot, of course, be imposed on private persons, it becomes the de facto standard for German orthography, since it must now be taught to all schoolchildren in German-speaking countries and must be adhered to in all government publications. The intent of the new rules is to make German orthography more consistent and reduce the number of exceptions to the rules, so as to make German orthography easier to learn. With regard to capitalization, the intent of the rules is to apply as consistently as possible the principle that nouns and words that function as nouns are capitalized, and to make the remaining exceptions to this principle easier to understand. One consequence of the spelling reform is that the guidelines for German capitalization given in Appendix A, rule A.40, no longer accurately reflect correct German capitalization according to the new rules. -

The History of English Spelling

9781405190237_1_pre.qxd 6/15/11 9:00 Page iii The History of English Spelling Christopher Upward and George Davidson A John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., Publication 9781405190237_1_pre.qxd 6/15/11 9:00 Page vi 9781405190237_1_pre.qxd 6/15/11 9:00 Page i The History of English Spelling 9781405190237_1_pre.qxd 6/15/11 9:00 Page ii THE LANGUAGE LIBRARY Series editor: David Crystal The Language Library was created in 1952 by Eric Partridge, the great etymologist and lexicographer, who from 1966 to 1976 was assisted by his co-editor Simeon Potter. Together they commissioned volumes on the traditional themes of language study, with particular emphasis on the history of the English language and on the individual linguistic styles of major English authors. In 1977 David Crystal took over as editor, and The Language Library now includes titles in many areas of linguistic enquiry. The most recently published titles in the series include: Christopher Upward and The History of English Spelling George Davidson Geoffrey Hughes Political Correctness: A History of Semantics and Culture Nicholas Evans Dying Words: Endangered Languages and What They Have to Tell Us Amalia E. Gnanadesikan The Writing Revolution: Cuneiform to the Internet David Crystal A Dictionary of Linguistics and Phonetics, Sixth Edition Viv Edwards Multilingualism in the English- speaking World Ronald Wardhaugh Proper English: Myths and Misunderstandings about Language Gunnel Tottie An Introduction to American English Geoffrey Hughes A History of English Words Walter Nash Jargon Roger Shuy Language -

Written Text

1 Swimming against the current Text of a “keynote address” for video delivery at the first World Congress of Korean Language, October 2020 신사 숙녀 여러분: 만나서 반갑습니다 ! I want to talk today (in English, I’m afraid) about what I believe is a consistent tendency in the historical evolution of scripts around the world. I shan’t call it a “linguistic universal”, because I don’t believe in Chomskyan biological universals of language. Languages are purely cultural products, and like other cultural products their development isn’t controlled by scientific laws. But the tendency I have in mind does seem to hold quite widely, and it can be explained, in terms of the demographic changes we associate with modernity. The reason why this topic may make a suitable opening for your conference is that the one unexplained exception to the tendency which I know of is in fact Korean script. But I’ll come to the case of Korean after I’ve spent some time discussing the tendency more generally. What I believe to be generally true, as I discuss in my book The Linguistics Delusion, is that in newly literate societies writing tends to be a matter of phonetic transcription – if the script is alphabetic, a newly-devised orthography will conform pretty closely to the principle “one sound, one symbol”; while as the script matures and the society modernizes, the orthography tends to evolve in the direction of what I’ll call “contrastiveness”, in the sense that the meaningful units of the language have consistent written shapes which are well-differentiated from the written forms of other meaningful units. -

Design of a Smart Braille Fitness Watch: Promoting Healthy Living For

Design of a Smart Braille Fitness Watch: Promoting Healthy Living for the Visually Impaired Unwana Michael Umoren David Ho Simon Connolly University of Bath University of Bath University of Bath United Kingdom United Kingdom United Kingdom [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Group 4 Group 4 Group 4 ABSTRACT impaired) are most likely to be less physically active than Physical activity plays a vital role in promoting healthy those without disabilities [9]. As a result of their less activity, living. Deficiency in physical activity increases vulnerability there are more susceptible to chronic diseases [9]. This to chronic diseases (such as cancer, obesity, etc. and reduced physical activity in visually impaired people is usually leads to a high rate of mortality. Physical inactivity is posed by barriers such as: reliance on other people exercise particularly common amongst the visually impaired than the assistance, transportation to the place of exercise and limited visually unimpaired. The visually impaired having decreased or no options available [8]. participation in physical activity due to certain barriers such This paper presents a prototype of a smart braille fitness as cost, transportation, etc, are prone to chronic diseases and watch for the visually impaired. The smartwatch aims at death in critical cases. To eliminate the barriers to physical promoting healthy living by increasing the physical activity activity experienced by visually impaired people, a prototype of visually impaired people. It employs the braille and audio of a smart braille fitness watch was designed. This paper technology to interact with the visually impaired user. -

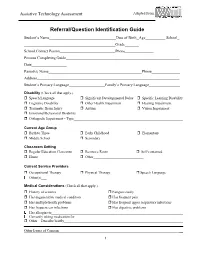

Referral/Question Identification Guide

Assistive Technology Assessment Adapted From Referral/Question Identification Guide Student’s Name Date of Birth Age School Grade School Contact Person Phone Persons Completing Guide Date Parent(s) Name Phone Address Student’s Primary Language Family’s Primary Language Disability (Check all that apply.) Speech/Language Significant Developmental Delay Specific Learning Disability Cognitive Disability Other Health Impairment Hearing Impairment Traumatic Brain Injury Autism Vision Impairment Emotional/Behavioral Disability Orthopedic Impairment – Type Current Age Group Birth to Three Early Childhood Elementary Middle School Secondary Classroom Setting Regular Education Classroom Resource Room Self-contained Home Other Current Service Providers Occupational Therapy Physical Therapy Speech Language Other(s) Medical Considerations (Check all that apply.) History of seizures Fatigues easily Has degenerative medical condition Has frequent pain Has multiple health problems Has frequent upper respiratory infections Has frequent ear infections Has digestive problems Has allergies to Currently taking medication for Other – Describe briefly Other Issues of Concern __ 1 Assistive Technology Assessment Adapted From Assistive Technology Currently Used (Check all that apply.) None Low Tech Writing Aids Manual Communication Board Augmentative Communication System Low Tech Vision Aids Amplification System Environmental Control Unit/EADL Manual Wheelchair Power Wheelchair Computer – Type (platform) Voice Recognition -

The Rechtschreibreform – a Lesson in Linguistic Purism

The Rechtschreibreform – A Lesson in Linguistic Purism Nils Langer, University of Bristol The Rechtschreibreform – A Lesson in Linguistic Purism 15 The Rechtschreibreform – A Lesson in Linguistic Purism1 Nils Langer The German spelling reform of 1998 generated an amazing amount of (mostly negative) reaction from the German public. Starting with a general overview of the nature of linguistic purism and the history of German orthography, this article presents a wide range of opinions of the spelling reform. The data is mostly taken from the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, either in the form of newspaper articles or letters to the editor, showing that the reform is rejected by untrained linguists (folk) for various political and pseudo-linguistic reasons, which, however, have in common a fundamenal misconception of the nature and status of both orthography in general and the 1998 spelling reform in particular. This articles argues, therefore, that the vast majority of objections to the spelling reform is not based on linguistic issues but rather based on a broadly politically defined conservative view of the world. On 1 August 2000 one of the leading German broadsheets, the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (FAZ), returned to using the old ‘bewährten’ spelling rules after one year of working with the new rules, arguing that the new rules had not achieved what they set out to do. The FAZ is on its own in this assessment, no other German newspaper followed its lead, and only two intellectual societies, the Hochschullehrerverband and the Deutsche Akademie für Sprache und Dichtung, returned to the old spelling after the FAZ’s decision. -

The Development of Writing and Preliterate Societies

The development of writing and preliterate societies Author: Cynthia Tung Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/bc-ir:107209 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2015 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. The development of writing and preliterate societies Cynthia Tung Advisor: MJ Connolly Program in Linguistics Slavic and Eastern Languages Department Boston College April 2015 Abstract This paper explores the question of script choice for a preliterate society deciding to write their language down for the first time through an exposition on types of writing systems and a brief history of a few writing systems throughout the world. Societies sometimes invented new scripts, sometimes adapted existing ones, and other times used a combination of both these techniques. Based on the covered scripts ranging from Mesopotamia to Asia to Europe to the Americas, I identify factors that influence the script decision including neighboring scripts, access to technology, and the circumstances of their introduction to writing. Much of the world uses the Roman alphabet and I present the argument that almost all preliterate societies beginning to write will choose to use a version of the Roman alphabet. However, the alphabet does not fit all languages equally well, and the paper closes out withan investigation into some of these inadequacies and how languages might resolve these issues. Contents 1 Introduction 5 2 What is writing? 6 2.1 Definition . 6 2.2 Types of writing . 6 2.2.1 Pictograms, logograms, and ideograms .