UNIVERSITY of STIRLING Kenneth Pardey the WELFARE of the VISUALLY HANDICAPPED in the UNITED KINGDOM

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Opposition-Craft': an Evaluative Framework for Official Opposition Parties in the United Kingdom Edward Henry Lack Submitte

‘Opposition-Craft’: An Evaluative Framework for Official Opposition Parties in the United Kingdom Edward Henry Lack Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of PhD The University of Leeds, School of Politics and International Studies May, 2020 1 Intellectual Property and Publications Statements The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. ©2020 The University of Leeds and Edward Henry Lack The right of Edward Henry Lack to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 2 Acknowledgements Page I would like to thank Dr Victoria Honeyman and Dr Timothy Heppell of the School of Politics and International Studies, The University of Leeds, for their support and guidance in the production of this work. I would also like to thank my partner, Dr Ben Ramm and my parents, David and Linden Lack, for their encouragement and belief in my efforts to undertake this project. Finally, I would like to acknowledge those who took part in the research for this PhD thesis: Lord David Steel, Lord David Owen, Lord Chris Smith, Lord Andrew Adonis, Lord David Blunkett and Dame Caroline Spelman. 3 Abstract This thesis offers a distinctive and innovative framework for the study of effective official opposition politics in the United Kingdom. -

Recall of Mps

House of Commons Political and Constitutional Reform Committee Recall of MPs First Report of Session 2012–13 Report, together with formal minutes, oral and written evidence Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 21 June 2012 HC 373 [incorporating HC 1758-i-iv, Session 2010-12] Published on 28 June 2012 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £0.00 The Political and Constitutional Reform Committee The Political and Constitutional Reform Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to consider political and constitutional reform. Current membership Mr Graham Allen MP (Labour, Nottingham North) (Chair) Mr Christopher Chope MP (Conservative, Christchurch) Paul Flynn MP (Labour, Newport West) Sheila Gilmore MP (Labour, Edinburgh East) Andrew Griffiths MP (Conservative, Burton) Fabian Hamilton MP (Labour, Leeds North East) Simon Hart MP (Conservative, Camarthen West and South Pembrokeshire) Tristram Hunt MP (Labour, Stoke on Trent Central) Mrs Eleanor Laing MP (Conservative, Epping Forest) Mr Andrew Turner MP (Conservative, Isle of Wight) Stephen Williams MP (Liberal Democrat, Bristol West) Powers The Committee’s powers are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in Temporary Standing Order (Political and Constitutional Reform Committee). These are available on the Internet via http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm/cmstords.htm. Publication The Reports and evidence of the Committee are published by The Stationery Office by Order of the House. All publications of the Committee (including press notices) are on the internet at www.parliament.uk/pcrc. A list of Reports of the Committee in the present Parliament is at the back of this volume. -

Interactive Tactile Representations to Support Document Accessibility for People with Visual Impairments

INTERACTIVE TACTILE REPRESENTATIONS TO SUPPORT DOCUMENT ACCESSIBILITY FOR PEOPLE WITH VISUAL IMPAIRMENTS Von der Fakultät für Informatik, Elektrotechnik und Informationstechnik der Universität Stuttgart zur Erlangung der Würde eines Doktors der Naturwissenschaften (Dr. rer. nat.) genehmigte Abhandlung vorgelegt von MAURO ANTONIO ÁVILA SOTO aus Panama-Stadt Hauptberichter: Prof. Dr. Albrecht Schmidt Mitberichter: Prof. Dr. Tiago Guerreiro Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 28. September 2020 Institut für Visualisierung und Interaktive Systeme der Universität Stuttgart 2020 to Valentina iv Abstract v ABSTRACT Since the early beginnings of writing, humans have exploited text layout and format as primary means to facilitate reading access to a document. In con- trast, it is the norm for visually impaired people to be provided with little to no information about the spatial layout of documents. Braille text, sonification, and Text-To-Speech (TTS) can provide access to digital documents, albeit in a linearized form. This means that structural information, namely a bird’s-eye view, is mostly absent. For linear reading, this is a minor inconvenience that users can work around. However, spatial structures can be expected to strongly contribute to activities besides linear reading, such as document skimming, revising for a test, memorizing, understanding concepts, and comparing texts. This lack of layout cues and structural information can provoke distinct types of reading hindrances. A reader with visual impairment may start reading multiple sidebar paragraphs before starting to read the main text without noticing, which is not optimal for reading a textbook. If readers want to revise a paragraph or access a certain element of the document, they must to go through each element on the page before reaching the targeted paragraph, due screen readers iterate through each paragraph linearly. -

Cultures and Traditions of Wordplay and Wordplay Research the Dynamics of Wordplay

Cultures and Traditions of Wordplay and Wordplay Research The Dynamics of Wordplay Edited by Esme Winter-Froemel Editorial Board Salvatore Attardo, Dirk Delabastita, Dirk Geeraerts, Raymond W. Gibbs, Alain Rabatel, Monika Schmitz-Emans and Deirdre Wilson Volume 6 Cultures and Traditions of Wordplay and Wordplay Research Edited by Esme Winter-Froemel and Verena Thaler The conference “The Dynamics of Wordplay / La dynamique du jeu de mots – Interdisciplinary perspectives / perspectives interdisciplinaires” (Universität Trier, 29 September – 1st October 2016) and the publication of the present volume were funded by the German Research Founda- tion (DFG) and the University of Trier. Le colloque « The Dynamics of Wordplay / La dynamique du jeu de mots – Interdisciplinary perspectives / perspectives interdisciplinaires » (Universität Trier, 29 septembre – 1er octobre 2016) et la publication de ce volume ont été financés par la Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) et l’Université de Trèves. ISBN 978-3-11-058634-3 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-058637-4 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-063087-9 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Control Number: 2018955240 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2018 Esme Winter-Froemel and Verena Thaler, published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck www.degruyter.com Contents Esme Winter-Froemel, Verena Thaler and Alex Demeulenaere The dynamics of wordplay and wordplay research 1 I New perspectives on the dynamics of wordplay Raymond W. -

The Study of Language This Best-Selling Textbook Provides an Engaging and User-Friendly Introduction to the Study of Language

This page intentionally left blank The Study of Language This best-selling textbook provides an engaging and user-friendly introduction to the study of language. Assuming no prior knowledge of the subject, Yule presents information in short, bite-sized sections, introducing the major concepts in language study – from how children learn language to why men and women speak differently, through all the key elements of language. This fourth edition has been revised and updated with twenty new sections, covering new accounts of language origins, the key properties of language, text messaging, kinship terms and more than twenty new word etymologies. To increase student engagement with the text, Yule has also included more than fifty new tasks, including thirty involving data analysis, enabling students to apply what they have learned. The online study guide offers students further resources when working on the tasks, while encouraging lively and proactive learning. This is the most fundamental and easy-to-use introduction to the study of language. George Yule has taught Linguistics at the Universities of Edinburgh, Hawai’i, Louisiana State and Minnesota. He is the author of a number of books, including Discourse Analysis (with Gillian Brown, 1983) and Pragmatics (1996). “A genuinely introductory linguistics text, well suited for undergraduates who have little prior experience thinking descriptively about language. Yule’s crisp and thought-provoking presentation of key issues works well for a wide range of students.” Elise Morse-Gagne, Tougaloo College “The Study of Language is one of the most accessible and entertaining introductions to linguistics available. Newly updated with a wealth of material for practice and discussion, it will continue to inspire new generations of students.” Stephen Matthews, University of Hong Kong ‘Its strength is in providing a general survey of mainstream linguistics in palatable, easily manageable and logically organised chunks. -

NEW ZEALAND POLITICAL STUDIES ASSOCIATION Conference CONFERENCE 2010 Programme

1 NEW ZEALAND POLITICAL STUDIES ASSOCIATION Conference CONFERENCE 2010 Programme Thursday 2 December 8.00 Registration Opens (Ground Floor, S Block) 9.15 Welcome Former Prime Minister and New Zealand Ambassador to the United States, and Chancellor of the University of Waikato, Jim Bolger (S.G.01) 9.30 Opening Address Bryan Gould The End of Politics (S.G.01) 10.30 Morning Tea Break 11.00 S.G.01 S.G.02 S.G.03 Roundtable: Engaging the Public in Current Issues in New Zealand Local Gender and Political Leadership the MMP Referendum Campaign Government Politics Convenor and Chair: Jennifer Curtin Convenor and Chair: Chris Rudd Convenor and Chair: Therese Jennifer Curtin Arseneau Jean Drage Women and Prime Ministerial What Will Auckland’s Reforms Mean for the Leadership: Beyond the Symbolic. MP Amy Adams Rest of Us? Ana Gilling Kate Stone Andy Asquith Gendered Conceptions of Power Managing the Metro Sector MP Rahui Katene Jane Christie Margie Comrie, Janine Hayward and Chris Maternal Legacies in Human Rights Sandra Grey Rudd Discourses as a Pathway to Political Media Coverage of the Local Body Elections Success: The Case of Michelle Bachelet and Cristina Fernández Laura Young E-Consultation and Local Government: Linda Trimble Creating Active Citizenship? When a Woman Topples a Man: Media Coverage of New Zealand Leadership ‘Coups’ 12.30 Lunch 1.00 S.G.01 S.G.02 S.G.03 S.1.01 Roundtable: Does the Roundtable: Marketing in The Politics of the Intangible Postgraduate Workshop: History of Political Thought Government: An Convenor and Chair: Peter -

11 Discourse Analysis Study Questions

5th edition This guide contains suggested answers for the Study Questions, with answers and tutorials for the Tasks in each chapter of The Study of Language (5th edition). This guide contains suggested answers for the Study Questions, with answers and tutorials for the Tasks in each chapter of The Study of Language (5th edition). © 2014 George Yule 2 Contents 1 The origins of language ................................................................................................ 4 2 Animals and human language ................................................................................... 11 3 The sounds of language ............................................................................................. 18 4 The sound patterns of language ............................................................................... 22 5 Word formation............................................................................................................. 26 6 Morphology ................................................................................................................... 32 7 Grammar ....................................................................................................................... 36 8 Syntax ............................................................................................................................ 41 9 Semantics ..................................................................................................................... 47 10 Pragmatics ................................................................................................................. -

Colorwatch: Color Perceptual Spatial Tactile Interface for People with Visual Impairments

electronics Article ColorWatch: Color Perceptual Spatial Tactile Interface for People with Visual Impairments Muhammad Shahid Jabbar 1 , Chung-Heon Lee 1 and Jun Dong Cho 1,2,* 1 Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Sungkyunkwan University, Suwon 16419, Gyeonggi-do, Korea; [email protected] (M.S.J.); [email protected] (C.-H.L.) 2 Department of Human ICT Convergence, Sungkyunkwan University, Suwon 16419, Gyeonggi-do, Korea * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Tactile perception enables people with visual impairments (PVI) to engage with artworks and real-life objects at a deeper abstraction level. The development of tactile and multi-sensory assistive technologies has expanded their opportunities to appreciate visual arts. We have developed a tactile interface based on the proposed concept design under considerations of PVI tactile actuation, color perception, and learnability. The proposed interface automatically translates reference colors into spatial tactile patterns. A range of achromatic colors and six prominent basic colors with three levels of chroma and values are considered for the cross-modular association. In addition, an analog tactile color watch design has been proposed. This scheme enables PVI to explore artwork or real-life object color by identifying the reference colors through a color sensor and translating them to the tactile interface. The color identification tests using this scheme on the developed prototype exhibit good recognition accuracy. The workload assessment and usability evaluation for PVI demonstrate promising results. This suggest that the proposed scheme is appropriate for tactile color exploration. Citation: Jabbar, M.S.; Lee, C.-H.; Keywords: color identification; tactile perception; cross modular association; universal design; Cho, J.D. -

R and D of the Div. of Engineering National Research Evaluation Of

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 081 136 EC 052 421 TITLE Evaluation of Sensory Aids for the Visually Handicapped. INSTITUTION National Academy of Sciences - National Research Council, Washington, D.C. SPONS AGENCY Social and Rehabilitation Service (DHEW), Washington, D.C.; Veterans Administration, Washington, D.C. PUB DATE 72 NOTE 194p.; Report on a conference sponsored by the Subcommittee on Sensory Aids Committee on Prosthetics R and D of the Div. of Engineering National Research Council (National Academy of Sciences, Washington, D. C., Nov. 11-12, 1971) EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$6.58 DESCRIPTORS Braille; Conference Reports; *Electromechanical Aids; *Exceptional Child Education; *Mobility Aids; *Sensory Aids; *Visually Handicapped ABSTRACT Presented are 11 papers given at a conference on the evaluation of sensory aids for the visually handicapped which emphasid mobility and reading aids beginning to be tested and distributed widely. Many of the presentations are by the principal developers or advocates of the aids. Introductory readings compare the role of evaluaticn in the prosthetics and orthotics program to the area of sensory aids and review the history of braille. Reading machines are considered in five papers with the following titles: "Evaluation of Certain Reading Aids for the Blind", "Experience in Evaluation of the Visotoner", "Optacon Evaluation Considerations", "Plans for the Evaluation of a High Performance Reading Machine for the Blind", and "A Digital Spelled-Speech Reading Machine for the Blind". The evaluation of mobility aids is examined in five papers with the following titles: "The VA--Bionic Laser Cane for the Blind", "Experience in Evaluation of the Russell Pathsounder", "Evaluation of the Ultrasonic Binaural Sensory Aid for the Blind", "Dearing Light Sensing Typhlocane--Model LST-3, and "Evaluation of Mobility Aids". -

Design of a Smart Braille Fitness Watch: Promoting Healthy Living For

Design of a Smart Braille Fitness Watch: Promoting Healthy Living for the Visually Impaired Unwana Michael Umoren David Ho Simon Connolly University of Bath University of Bath University of Bath United Kingdom United Kingdom United Kingdom [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Group 4 Group 4 Group 4 ABSTRACT impaired) are most likely to be less physically active than Physical activity plays a vital role in promoting healthy those without disabilities [9]. As a result of their less activity, living. Deficiency in physical activity increases vulnerability there are more susceptible to chronic diseases [9]. This to chronic diseases (such as cancer, obesity, etc. and reduced physical activity in visually impaired people is usually leads to a high rate of mortality. Physical inactivity is posed by barriers such as: reliance on other people exercise particularly common amongst the visually impaired than the assistance, transportation to the place of exercise and limited visually unimpaired. The visually impaired having decreased or no options available [8]. participation in physical activity due to certain barriers such This paper presents a prototype of a smart braille fitness as cost, transportation, etc, are prone to chronic diseases and watch for the visually impaired. The smartwatch aims at death in critical cases. To eliminate the barriers to physical promoting healthy living by increasing the physical activity activity experienced by visually impaired people, a prototype of visually impaired people. It employs the braille and audio of a smart braille fitness watch was designed. This paper technology to interact with the visually impaired user. -

Text Cut Off in the Original 232 6

IMAGING SERVICES NORTH Boston Spa, Wetherby West Yorkshire, LS23 7BQ www.bl.uk TEXT CUT OFF IN THE ORIGINAL 232 6 ORGANISATIONAL CHANGE Between 1983 and 1989 there were a series of important changes to Party organisation. Some of these were deliberately pursued, some were more unexpected. All were critical causes, effects and aspects of the transformation. Changes occurred in PLP whipping, Party finance, membership administration, disciplinary procedures, candidate selection, the policy-making process and, most famously, campaign organisation. This chapter makes a number of assertions about this process of organisational change which are original and are inspired by and enhance the search for complexity. It is argued that the organisational aspect of the transformation of the 1980s resulted from multiple causes and the inter-retroaction of those causes rather than from one over-riding cause. In particular, the existing literature has identified organisational reform as originating with a conscious pursuit by the core leadership of greater control over the Party (Heffernan ~\ . !.. ~ and Marqusee 1992: passim~ Shaw 1994: 108). This chapter asserts that while such conscious .... ~.. ,', .. :~. pursuit was one cause, other factors such as ad hoc responses to events .. ,t~~" ~owth of a presidential approach, the use of powers already in existence and the decline of oppositional forces acted as other causes. This emphasis upon multiple causes of change is clearly in keeping with the search for complexity. 233 This chapter also represents the first detailed outline and analysis of centralisation as it related not just to organisational matters but also to the issue of policy-making. In the same vein the chapter is particularly significant because it relates the centralisation of policy-making to policy reform as it occurred between 1983 and 1987 not just in relation to the Policy Review as is the approach of previous analyses. -

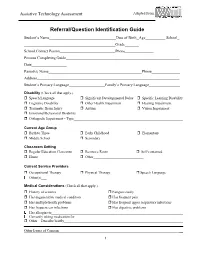

Referral/Question Identification Guide

Assistive Technology Assessment Adapted From Referral/Question Identification Guide Student’s Name Date of Birth Age School Grade School Contact Person Phone Persons Completing Guide Date Parent(s) Name Phone Address Student’s Primary Language Family’s Primary Language Disability (Check all that apply.) Speech/Language Significant Developmental Delay Specific Learning Disability Cognitive Disability Other Health Impairment Hearing Impairment Traumatic Brain Injury Autism Vision Impairment Emotional/Behavioral Disability Orthopedic Impairment – Type Current Age Group Birth to Three Early Childhood Elementary Middle School Secondary Classroom Setting Regular Education Classroom Resource Room Self-contained Home Other Current Service Providers Occupational Therapy Physical Therapy Speech Language Other(s) Medical Considerations (Check all that apply.) History of seizures Fatigues easily Has degenerative medical condition Has frequent pain Has multiple health problems Has frequent upper respiratory infections Has frequent ear infections Has digestive problems Has allergies to Currently taking medication for Other – Describe briefly Other Issues of Concern __ 1 Assistive Technology Assessment Adapted From Assistive Technology Currently Used (Check all that apply.) None Low Tech Writing Aids Manual Communication Board Augmentative Communication System Low Tech Vision Aids Amplification System Environmental Control Unit/EADL Manual Wheelchair Power Wheelchair Computer – Type (platform) Voice Recognition